Zuñi Pueblo:

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

1629–1632; 1692; 1706+; 1968

With Spanish hegemony centered on the upper Rio Grande, the western villages of the Zuñi and the Hopi remained peripheral to the missionary enterprise. The Zuñi village of Hawikuh had been the first to confront the Fray Marcos de Niza party in the mid-1500s. That confrontation resulted in the death of the "scout" Esteban and the ambiguous substantiation of the existence of the Seven Cities of Cíbola. What the friar took for gold may have been only mud and stone seen in the setting sun, but his subsequent report played a pivotal role in the move to colonize what is now New Mexico.

Traces of occupation in the Cíbola cultural area date as far back as the ninth century B.C . and are believed to be signs of a hunting culture; by the beginning of the Christian era it had been superseded by an agrarian-based society.[1] The development of a sedentary agricultural group occasioned a more substantial architecture and led to a conglomerate dwelling with storage spaces that was oriented along a northeast-southwest axis. Although the archaeological evidence does not present an absolutely conclusive picture, the Cíbola villages were probably part of the extensive system of "outlyers" that centered on the Anasazi settlements of Chaco Canyon. Characteristics of the parent culture—at times multistoried, aboveground dwellings and the ceremonial kiva—marked Cíbolan construction well into the thirteenth century.

After this time a shift in site patterns occurred, with the villages transferred to higher elevations, perhaps to capture increased rainfall during an extended period of drought. Paralleling the transference of dwellings from mesa top to cave at Mesa Verde, the Cíbolan pueblo of the late thirteenth century displayed a pronounced defensive form. Against whom is not known. And like the structures of Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde, the Cíbolan buildings were deserted early in the fourteenth century. As Steven Le Blanc noted, many gaps remain to be breached, and many questions are still to be answered. Over time attrition in population concentrated the people in fewer villages so that by the time of the Spanish entrance in 1540, there were only "six or seven pueblos along the Zuñi River."[2]

The chronicle of Spanish contact with the Zuñi pueblos, while a few years longer than that of other pueblos, is typical. Coronado used the pueblos as his point of departure; he was lured eastward away from the villages by the promise of more immediate reward. Antonio de Espejo crossed Zuñi lands in 1583, followed by Juan de Oñate in 1598. At this time, Oñate obtained the customary "Act of Obedient Vassalage" promising respect for the king and

30–1

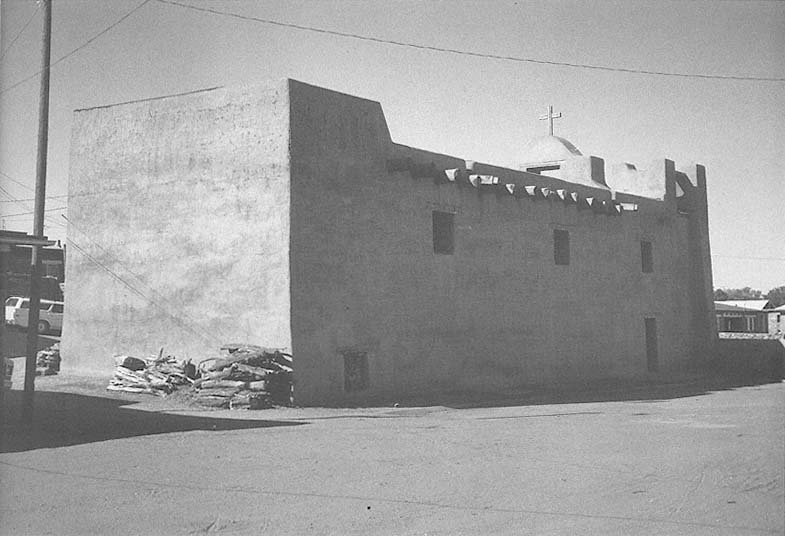

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

Seen from the rear, the mass of the church reveals its plan: a single nave without transepts.

[1984]

the church.[3] Some thirty years later the first mission was founded. The considerable expedition that reached Zuñi in June 1629 included the provincial governor, Manuel de Silva Nieto, and Custodian Estevan de Perea. The Spanish made a good show of it: "And to give that people to understand the veneration due to the Priests, all the times that they arrived where these were, the Governor and the soldiers kissed their feet, falling upon their knees, cautioning the Indians that they should do the same. As they did; for as much as this example of the superiors can do."[4]

As a setting for the mass and a residence for the religious, "a house was bought. . . . And hoisting the triumphal standard of the Cross, possession was taken. . . . To the first fruits of which there succeeded, on the part of the soldiers, a clamorous rejoicing, with a salvo of arquebusses; and in the afternoon, skirmishings and caracolings of the horses. . . . There were knowing people of good discourse; beginning at once to serve the Religious by bringing him water, wood, and what was necessary."[5] Perea probably confused fear and discretion here with compulsion and acceptance.

The church, however, required a more elaborate expression. "And in order to make this art spectacular, he ordered a high platform to be built in the plaza, where he said mass with all solemnity, and baptized them . . . singing the Te Deum Laudamos , etc; and through having so good a voice, the Father Fray Roque—accompanied by the chant—caused devotion in all."[6] Fray Francisco de Letrado succeeded Fray Roque de Figueredo in 1630 or 1631 with three missions under construction in the Zuñi area.[7] Two principal missions were founded at Hawikuh, one dedicated to La Purísima Concepción and the other to Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria at Halona. The third church at Kechipauan never reached completion.[8] Benavides described the churches as "adorned and tidy" and credited the successful work to the devotion of the religious and the financial support of the crown.[9] These successes were short-lived. On February 22, 1632, as Fray Francisco de Letrado attempted to gather the flock into his church, a volley of arrows felled him. A second priest shared his fate five days later. In what was to be their typical response, the Zuñi fled to the protection of the nearby mesa, "Thunder Mountain (called Dowa-Yallone by the Zuñis) and fearing retaliation, remained there for three years."[10]

In 1643 the two missions were reestablished, with the priest assigned to Halona. At the very edge of the empire, this assignment was miserable at best. One Fray José succinctly remarked, "If it had been

30–2

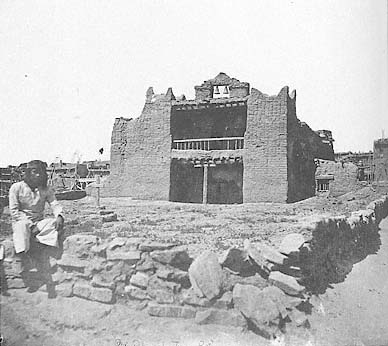

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

1880s

Late in the nineteenth century erosion had removed the protective outer

layer of plaster, with severe deterioration from the towers and bell arch

downward.

[Museum of New Mexico]

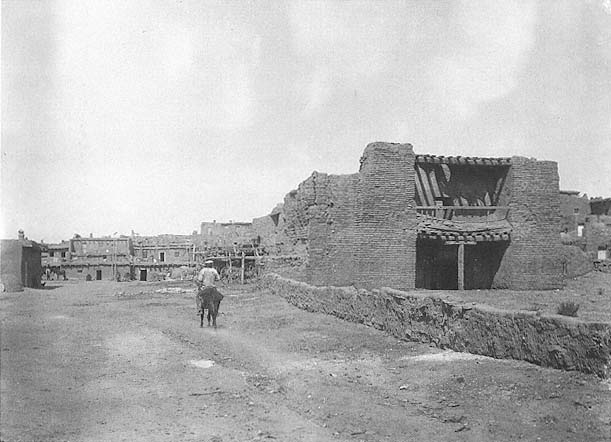

30–3

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

At the nineteenth century's end Nuestra Señora was quickly falling into ruin, its sagging balcony propped by a

single post.

[Hyde Expedition; Negative 4630, courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History, Department of Library

Services]

chosen for a prison for those guilty of the gravest crimes there would have not been a more severe decision."[11]

In the decades just after midcentury the weakening of Spanish power and its distance from the Zuñi nation, compounded by the famine brought on by drought, led to more numerous and violent raids by the Apache. A report ascribed to 1644 implied that the church had been destroyed and the mission abandoned. "The province of Zuñi [was] severely punished for having destroyed churches and conventos and for having killed one of the ministers who served in the work of conversion. . . . In this province there are 1,200 Indians who have asked for ministers once again."[12] In 1672 an Apache attack on the village left the missionaries dead and the church again destroyed. The Zuñi joined the rebellion of 1680, during which the resident priest was killed—although certain tales have him abandoning the cloth and joining the tribe.[13]

The church itself was ruined. Again the natives fled to the defensive security of the mesa top and were living there when Vargas coaxed them to return to their fields and restore the church. At the turn of the eighteenth century a detachment of eleven soldiers was dispatched to Zuñi from Santa Fe to maintain order in the village and to ensure the restoration of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, which by 1699 had badly deteriorated.[14]

The assignment at Zuñi was never an easy one, and the years of relative calm were also years of dire frustration. By midcentury, two priests served at Halona (a quota that was rarely filled). One incident in 1763 led to three Spanish dead and the traditional Indian departure for the higher elevations. Within two years the priest returned and convinced the Zuñi to again tend their crops. Tamarón was unable to reach Zuñi on his visitation of 1760, thwarted by intense heat and its effect on the pack animals. He was informed, however, that it was the largest pueblo in the province, with 182 families and 664 persons. The patron saint of the mission was Our Lady of Guadalupe, and the "church was good."[15]

Domínguez included Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe on his inspection tour, noting that the walls of the church were "nearly a vara thick." At this time the population was given as 1,617 persons in 396 families,[16] a drastic contrast to Benavides's figure of 10,000 souls living in ten or eleven pueblos a century and a half earlier,[17] although this was probably an inflated figure. The church, as Domínguez described it, was quite typical: built of adobe with a single nave, several steps up to the sanctuary, a choir loft "in the usual place," two windows on the

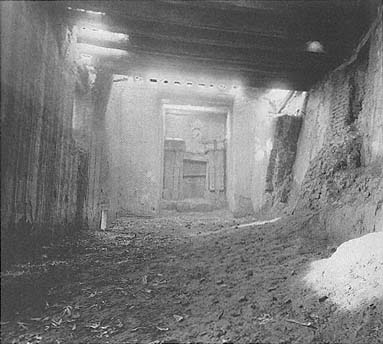

30–4

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

1890s?

Interior of nave in ruined state. The walls have deposited material into the

nave, and portions of the roof have collapsed.

[I. W. Tauber, Museum of New Mexico]

30–5

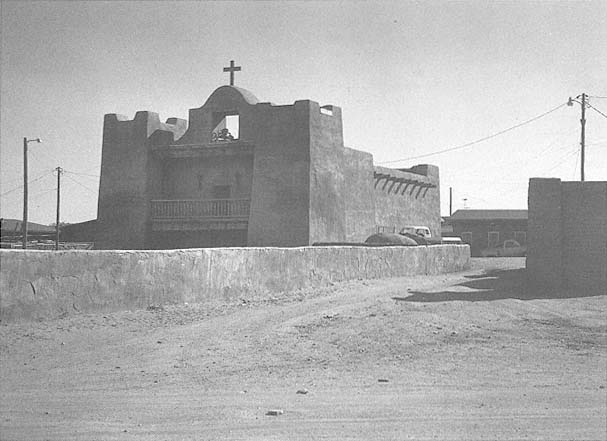

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

Nuestra Señora seen over the cemetery wall.

[1984]

30–6

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, Plan

[Sources: Caywood, The Restored Mission , and Smith,

"Seventeenth-Century Spanish Missions"]

right side, and a transverse clerestory. The front doors, however, were simpler in construction than the inset entrance beneath the balcony visible in photos from the late nineteenth century. "The door is squared, with a wooden frame instead of masonry, with two paneled leaves, no lock except the cross bar."[18] The convento, configured as a square, abutted the church to the south and was fronted by the portico of a porter's lodge that might have doubled as an open-air chapel.

In the early nineteenth century the Navajo and Apache terror increased, and by 1821 the residence of priests at Zuñi was sporadic. In the past the church had had a considerable impact on the living pattern of the villages, but by midcentury that presence was negligible. The new bishop, Jean-Baptiste Lamy, visited the village in 1863, and priests continued to hold mass only on an irregular basis thereafter. By 1881 the merciless elements had already taken their toll. Bourke sketched the "ruined church."

The windows never had been provided with panes and were nothing but large apertures barred with wood. The carvings about the altar had at one time included at least half a dozen angles as caryatids, of which two still remained in position. The interior is in a ruined state, great masses of earth have fallen from the north wall; the choir is shaky and the fresco has long since dropped in great patches upon the floor. The presence of five or six different coats of this shows that the edifice must have been in use for a number of years.[19]

A Wittick photograph of 1890 shows the tired form of the old church, its adobe towers withered, its sagging balcony propped by a single post. Some time early in the twentieth century the north wall was rebuilt south of its original location, and new timbers and roofing were installed.[20]

Isleta's Father Docher, writing in 1913, was skeptical of Zuñi piety. "The Zuñis are more numerous," he declared. "But they are half still barbarians."[21] Around 1905 parts of the roof had been rebuilt, and the width of the nave had been reduced by ten feet and its length by twenty—but who accomplished the work is not known.[22] During the 1920s the village was split on whether to reinstate a Catholic mission or a Protestant church; the pro-Catholic force eventually succeeded.

The church standing today, excavated and last restored in the late 1960s by the National Park Service under the direction of Louis R. Caywood, is only a part of the original complex. Once flanked by the structures of the pueblo—then a multistoried configuration recalling the form of today's Taos pueblo—it now stands tall among the houses of the village. The church is basically a single-nave plan without transepts. The campo santo still fronts the church, divided in burial practice with women to the north and men to the south.[23] Replastered in hard stucco, the church shares the color of the surrounding dwellings. Today, it lacks the original sacristy, baptistry, and convento.

Decoration seems to have played an important part in the church's interior. Matilda Coxe Stevenson, the wife of an army officer at nearby Fort Wingate with an interest in ethnography, reported in 1879 that the nave was decorated with Zuñi religious images, the pieces of which Bourke recorded only two years later.[24] Today the church at Zuñi is considerably reduced from its more expansive structure of two centuries ago, its walls displaying a hardness uncharacteristic of the more malleable mud plaster. Inside painted images by Alex Seowtewa enliven the nave. Outside the flowers of the small burial ground provide intense spots of color that relieve the almost monochrome siena of the church, pueblo, and earth itself.

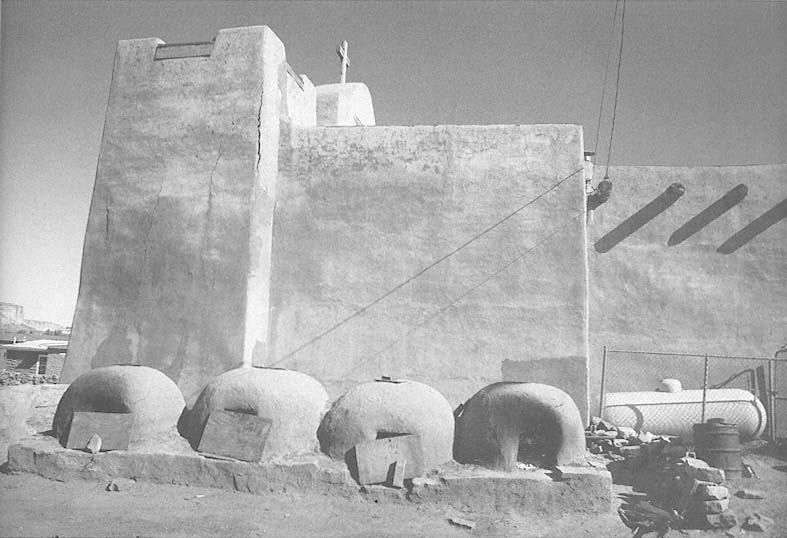

30–7

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

The sculptured forms of the ovens provide a foil for the prismatic mass of the church.

[1984]