Acoma Pueblo:

San Esteban

c. 1630; 1696–1700; 1924; 1926

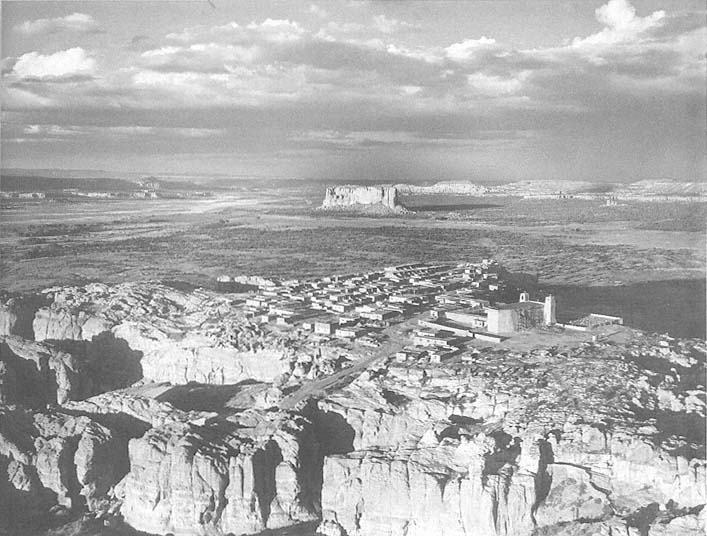

West of Albuquerque, past the pueblo of Laguna, and south of Interstate 40 lies Acoma, the Sky City. The approach to Acoma leads through a vast canyon that extends for twenty miles with no apparent exit, its edges severely circumscribed by the steep cliffs and mesas surrounding the valley. There are two principal interruptions to the sweep of the level canyon floor. The first is Enchanted Mesa, a large piece of rock isolated from the surrounding cliffs like a piece of debris left on the beach after a particularly high tide. The second is the mesa on which Acoma pueblo is perched.

The Acoma are said to have first occupied the top of Enchanted Mesa, which is higher still and yet within sight of the mesa top they now inhabit [Plate 1]. One day, legend tells, an enormous storm caused a fissure in the cliff that severed the fragment containing the only access to Enchanted Mesa, a series of foot and hand holes worn in the side of the rock. Up on the butte three old women, either too old or too infirm to work in the fields, were left to finish out their lives. The majority of the people were isolated in the valley below, and they had to seek a new life and a new home in the closest defensive stronghold they could find. And so they began anew on a second piece of rock hardly more, and probably less, hospitable than the first. The settlement of Acoma then parallels and recreates the settlement pattern of Mesa Verde, although here the order of habitation was somewhat reversed. On the summit, some seventy-odd acres, the Acoma Indians built their new pueblo.

It would be difficult, it not impossible, to conjure up a more dramatic, poetic, and less likely place to found a community. Next to nothing of life's necessities, except defense, was found on the cliff top. Water supplies were limited to a cistern pool and incidental accumulations of rainwater. At other times water was brought from the valley floor, carried up the nearly four hundred feet by hand or on the head, in jars from distant springs. There was no agricultural land; in fact, there was almost no soil at all on the mesa. Only sky and protection were abundant.

And yet the setting and those structures that have been constructed and resolutely dwell on this rock strike the basic chords of harmony and inevitability. Lummis was clearly struck by the landscape: "And in its midst lies a shadowy world of crags so unearthly beautiful, so weird, so unique, that it is hard for the onlooker to believe himself in America, or upon this dull planet at all."[1] So steep is the rock surface that it actually overhangs in places. And until well into this century little more than a donkey

29–1

Acoma Pueblo

The Sky City and San Esteban, with the Enchanted Mesa beyond.

[Dick Kent, 1960s]

29–2

San Esteban, Plan

[Source: Kubler, The Religious Architecture , based on HABS]

path provided access. Before, one climbed a series of handholds with food, building materials, or water. It was not until the 1950s that a road permitting automobile access was cut and then only because a motion picture was being filmed on the site.

Fray Marcos de Niza heard of the pueblo, whose name he learned as Ahuacus, during his travels in 1539. Coronado passed by Acoma. In 1581 Espejo actually visited the pueblo and remained there as a guest for three days.

"The Acomas received the wondrous strangers kindly, taking them for gods,"[2] or so the Spanish chronicles read. In 1598 they became vassals of the Spanish crown after submitting to Oñate's act of obedience and homage. Initially their submission was short-lived. Oñate, experiencing difficulty in his campaigns, dispatched Juan de Zaldívar with some troops to collect supplies at Zuñi. En route they camped below the mesa. "Zaldívar and some of his men," Marc Simmons related,

were lured to the summit and a horde of painted and befeathered warriors fell upon them. One after another, the sword-swinging Spanish went down, until the few who remained were driven to the edge of the cliff. There was no choice; they jumped. Twenty-year-old Pedro Robledo smashed against the rocky wall, his body tumbling to the base like a broken doll. Three other soldiers landed in sand dunes swept by the winds against the foot of the mesa. They were gathered up, dazed, by the four members of the horse guard who remained below.[3]

Oñate learned of the battle and the death of ten of his men. He dispatched Vicente de Zaldívar from San Gabriel on January 21, 1599, to deal retribution to the Acoma. The battle was bloody, and at its conclusion the Spanish emerged victorious. Hundreds of Acoma were dead. Oñate, intent on establishing a precedent for dealings with Indian uprisings, handed down a series of sentences ranging from mutilation to servitude, even though the pueblo was already decimated. From that time on there was little Acoma reaction against the Spanish.[4]

Acoma was first assigned to Fray Jerónimo de Zárate Salmerón, who kept charge from 1623 to 1626.[5] It is said that Fray Juan Ramírez walked to Acoma from Santa Fe to assume his post as Zárate Salmerón's successor and to live among the Indians for a number of years. To him is usually assigned credit for building the first church. Benavides was clearly astonished by the pueblo, calling it "the most amazing in strength and location that could be found in the whole world. It has to all appearances, more than two thousand houses, in which there

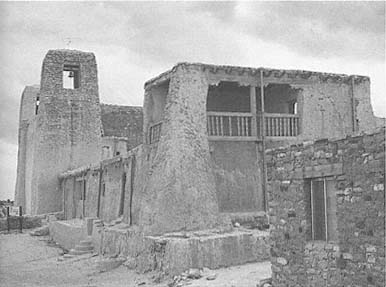

29–3

San Esteban

The handsome, boatlike shape of the nave seen from the southwest. Without a plaster top coat, the stone and adobe

mixture is apparent.

[1981]

29–4

San Esteban

The twin towers of the principal facade seen across the cemetery, with

the remnants of the convento to the right.

[1986]

must be more than seven thousand inhabitants."[6] In 1644 the church was described as "the most handsome [in the Custodia?], the paraphernalia of public worship is abundant and unusual; [the church] has a choir and organ; there are 600 souls under its administration."[7] During the Pueblo Revolt the resident friar, Fray Lucas Maldonado, perished while the church was believed to have been destroyed.

Whether the church was demolished completely or damaged at all during the revolt is still a matter of dispute, however. If the church has remained with its original walls on the same site, it has a rightful claim to being the oldest continually used church in New Mexico. Yet there are opinions to the contrary. Walter, for example, said, "Despite tradition, Hodge declares that no trace of it [the original structure] remains today except some carved beams which form part of one of the houses of the old north tier."[8] Today, however, several scholars believe that at least portions of the current structure predate the Reconquest, although a major reconstruction took place between 1696 and 1700. The bell in the northeast tower is inscribed "San Pedro, 1710," but it could have been added at a later date. Fray Juan Álvarez visited Acoma in 1705 and found the inventory scant and a single priest, Fray Antonio Miranda, repairing the church by himself. Domínguez, however, stated that "this church was inaugurated in the year 1725" and tentatively credited Fray Miranda with its construction.[9] The attribution could apply to a substantial renewal of the church, but the exact explanation of how much was rebuilt has remained elusive.

The church of San Esteban of Acoma is an enormous church measuring 150 feet in length and 33 feet in width. It strikes a certain note of irony that this, the largest existing mission structure, serves the most inaccessible congregation. The church is without transepts. At the sanctuary the apse end of the nave angles prominently, extending the sense of its length. The walls are nearly 10 feet thick and built of massive amounts of adobe and stone, approximately twenty thousand tons, according to Riley writing in 1924 at the time of its restoration.[10] A choir loft spans the rear of the nave at the eastern end.

The vigas that support the roof are fourteen inches square and forty feet long. They were reportedly brought to the mesa—but not by horse, ox, or wheel—from the San Mateo Mountains twenty miles distant. The inside height of the nave is almost fifty feet, equaling the loftiness of the Salinas missions, all of which now lie in ruins.

Neither loose rock nor soil was found on the mesa. As a result, it was necessary to import the

earth in which to bury the dead. "There are no burials in the church," Domínguez recorded, "because the rock prevents this, and in order to cover it, it was filled with earth to a depth of about half a vara."[11] But loose soil in the campo santo would have been blown away by strong winds, and so a retaining wall of stone brought from the valley was built east of the church (a wall that measures forty-five feet high in places) to form a giant box to contain the good soil for a Christian burial. The ten years' work required to construct the church is impressive, but tradition has it that an additional forty years were spent filling the box. If the pueblo did indeed have 760 Christians in 1705, it should also have had two resident priests. But in 1821 it had none.

On his visitation in 1760 Tamarón was obviously moved by the site and the missionary efforts at Acoma. "It is the most beautiful pueblo of the whole kingdom," he wrote, "with its system of streets and substantial stone houses more than a story high. The priest's house has an upper story and is well arranged."[12] (This convento, arranged in a square and not accessible to the public, still exists.) Atypically, it was sited north of the church—not a good exposure, but where land was available. Tamarón mentioned that Fray Pedro Ignacio Pino had learned enough of the native tongue to listen to confession but required the aid of some seven interpreters to give penance in return. The bishop remarked calmly that the friar "has had to whip them, and he keeps them in order, although he is not up to date with regard to confession."[13] Second only to the discussion of language was Tamarón's expressed amazement at the agility and ability of the women to carry water to the mesa's crest.

Sixteen years later Domínguez expressed unusual respect for the congregation: "There is not even a brook, earth to make adobes, or a good cart road. Therefore, it is necessary to prevent any preconception in order to achieve even a confused notion of this place. This makes what the Indians have built here of adobes with perfection, strength, and grandeur, at the expense of their own backs, worthy of admiration." He noted the entrance to the baptistry (no longer extant) under the choir to the left and the paintings and ornamentation of colored earth that embellished the interior. In total effect, "the interior is pleasant, although bare."[14] The barrenness of the mesa top impressed Domínguez, and he devoted several comments to the provision of water. In the convento, for example, "some little peach trees . . . are watered by hand."[15] The service to the mission friar consisted mostly of water bearing.

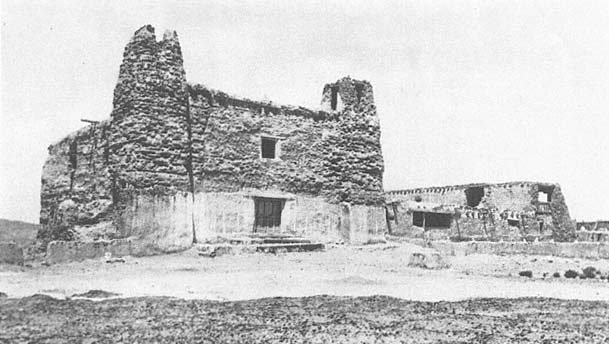

29–5

San Esteban

1897

The church, convento, and the retaining wall of the cemetery seen

from across the mesa top.

[Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation]

29–6

San Esteban

1902

Erosion by wind and rain had taken their toll on the body of the church early in the twentieth century. Although the

base—more easily within human reach—had been maintained, the upper portions of the walls, especially the towers,

were deeply rutted.

[Museum of New Mexico]

29–7

San Esteban

circa 1915

The great box containing soil for the Christian burial reads clearly in the

left portion of the photo.

[Museum of New Mexico]

29–8

San Esteban

The convento and San Esteban seen from the north.

[1981]

"Twelve Indian women . . . bring twelve small jars of water to be used daily. . . . The reason for such a large number of water carriers is that the water . . . is very far away, and to avoid frequent trips a good deal is brought at one time.[16] On the summit water assumed the status of currency.

Shortly after Domínguez's visit Acoma became a visita of Laguna due to the ravages of smallpox in the Acoma community. Also, Acoma was isolated and difficult to reach, whereas Laguna stood on the main route between the Rio Grande pueblos such as Isleta and Sandia and the western missions at Zuñi.

"The approach is one of the most romantic imaginable, and brings to the mind of the climber all that he has ever heard or read of ascent in the Andes," Bourke wrote, stopping at Acoma while heading east.[17] "There is an old church of massive proportions but without symmetry or beauty in which Catholic priests still held Divine Service once a month."[18] Since Bourke's watercolor sketch depicted the symmetrical structure much as we see it today, he must have used the word symmetry in its classical associations with proportion. He also referred to a "ruined church of San José de Acoma: 80' broad, 55' high, towers 70' × 13' broad," a curious note.[19]

By the turn of the twentieth century the condition of the church had reached a critical level. Contemporary photos show that the erosion of the towers and the spalling of the mud plaster from the south wall had caused considerable deterioration. The tower bases were severely eroded by water and wind. With funds from the Committee for the Reconstruction and Preservation of New Mexico Mission Churches, restoration work commenced under the supervision of Lewis Riley and Sam Huddleston acting in conjunction with architect John Gaw Meem in Santa Fe.[20] At that late date the nearest railroad stop was still fifteen miles away at Acomita, which meant that the final part of the journey—and the lifting of building materials to the top of the peñol—had to be accomplished by human and animal strength. First priority was given to the roof, which leaked seriously and threatened the destruction of the nave.

Even in 1924, Riley reported, the younger men of the village lived, not in the Sky City, but in the surrounding settlements at Acomita and McCarty's. The rebuilding was undertaken cooperatively, with a "community effort which could hardly be duplicated among our own people."[21] The water was transported in five-gallon casks and steel barrels and was hauled on donkeys the two miles from the nearest spring. (Acoma still does not have a regular

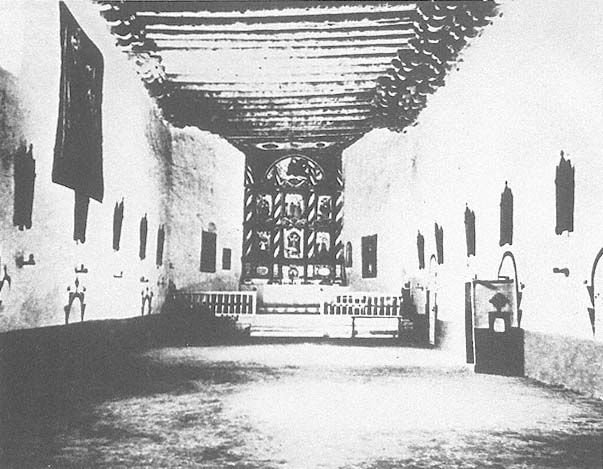

29–9

San Esteban

1940

Free of pews and still with earthen floor, the interior appears monumental.

[Wilder, Taylor Museum, Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center]

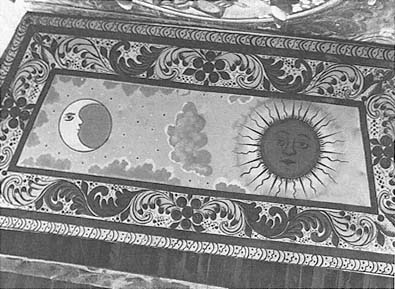

29–10

San Esteban

Detail of the upper portion ceiling of the altarpiece.

[Museum of New Mexico]

source of water.) The women augmented these efforts in the traditional way by bearing water to the precipice in buckets and ollas. The roof work was completed in six weeks using lumber from Arizona and roofing materials from Denver, both brought via rail. "The convento is rapidly falling into ruins, but it preserves as yet most of its former beauty and could be restored with comparatively little expense," Riley wrote.[22] He had also hoped to repair the towers and the exterior plastering, but these had to wait until the works of 1926–1927.

The 1926 restoration was a community effort with cooperative decisions determining the allocation of human resources. On September 12, 1926, it was decided that all members of the pueblo would assemble and for three days pack and carry dirt up to the church site. From September 15 onward there would be a crew of fifteen men, to be rotated each week, who would work on the repairs until the winter weather intervened. On September 9 a large herd of burros was discovered by B. A. Reuter, who had succeeded Lewis Riley as superintendent, and these were commandeered to haul earth. Thus, drawing on the ageless tradition of human and animal labor, the church reconstruction began.

The south wall was given the first attention; the church roof shed its water toward the south, and both this splashing and the water driven back onto the wall surface by the prevailing winds had gouged out a good portion of the structure. This destructive force was exacerbated, of course, by the force of the storms themselves. After repair the canales were extended by five feet to alleviate the problem. The upper part of the wall had receded almost thirty inches between the base and the top, and "it is quite clear that the principal part of this batter is the effect of erosion."[23] The south wall had eroded an average of ten to eighteen inches to a height of about eight feet, seriously undercutting the base of the structure. The west wall of the south tower, taking the brunt of the wind and rain forces, was also seriously undermined.

The church was built primarily of adobe but incorporated some pieces of local rock. It was virtually impossible to get any new rock from the mesa because all the best material had been previously used in house construction. Photographs taken near the end of the restoration or shortly thereafter reveal a very finished and polished version of the Acoma church, looking almost as if the final polishing were a bit too perfect to be comfortable.

Today San Esteban is in a good state of repair following further preservation efforts in 1975 and roof repairs in 1981.[24] The south facade, which is normally out of bounds to visitors, often lacks some of its plaster, as it seems to be an almost impossible task to maintain this skin intact. Morning is the best time to view the church, when the facade catches the sunlight and reflects it back across the campo santo. The interior of the nave is whitewashed and sports a pink wainscot with painted decorations that recall the motifs used on the exquisite pottery for which Acoma is noted. The absence of pews is still noticeable, and the altarpiece provides the single focus to the nave. Above the altarpiece are paintings of the sun and moon, native motifs mixed into the religious framework of Catholic iconography. Acoma remains a world apart.