Laguna Pueblo:

San José de la Laguna

c. 1700

As one heads west on Interstate 40, mile after mile of desert and mesa forms slip by almost as a continuous extrusion. Only the rhythm imposed on the topography by the basalt mesas and buttes punctuates the first hundred miles west of Albuquerque. There is a singular exception: Laguna Pueblo. Seen from the road, the pueblo sits squarely on its rise as an island in the land. The stone and adobe buildings are mud plastered to the color of the earth, and homogeneity and harmony pervade the various elements of the village. Atop the stacked dwellings, the visual focus is the bulk and whiteness of the pueblo's church: San José de la Laguna.

The founding of the settlement is not precisely ascertained. Prince and other writers attributed its dating to 1699, but this is only the date of Spanish recognition after the Reconquest. Walter wrote that Laguna was "founded in 1689 by rebel Queres from Santo Domingo, Cochiti, Sia, and evidently Acoma, and may also include some of the Queres which had fled to Hopi Country."[1] Prince asserted that the pueblo's inhabitants were primarily people from Acoma who had entered the area in search of better farming and hunting lands and had eventually founded a permanent settlement augmented by emigrants from Zia and Zuñi.[2] Ellis qualified these interpretations by suggesting that the settlement predated 1698–1699 and that this accepted date was based on the first Spanish identification of July 1699, when Governor Cubero traveled through the district demanding the submission of the native population.[3]

A dam across the San Jose River, which passes at the foot of the rise, formed the lake from which the native name Kawaik derived, translated into Spanish as Laguna. The pueblo was unusual in that farming shared economic importance with sheep raising. According to tradition, the Laguna originated on the other side of the lake, possibly from the Anasazi of the Four Corners region, and settled in their current lands around the beginning of the fifteenth century. Ellis believed that the Spanish initially regarded Laguna as part of Acoma and that this is why we do not have a separate description of the pueblo and its population.[4] By 1706 a small chapel was under construction in Laguna, administered as a visita of Acoma.[5]

Bishop Tamarón visited Laguna on his way from Zia and Jemez to Zuñi and commented at length about the aridity of the land and the difficulty of the journey given that "the sun burned as if it were shooting fire."[6] He was a bit disconcerted about the resident priest's inability to speak and receive confession in the native Keres. Tamarón listed the

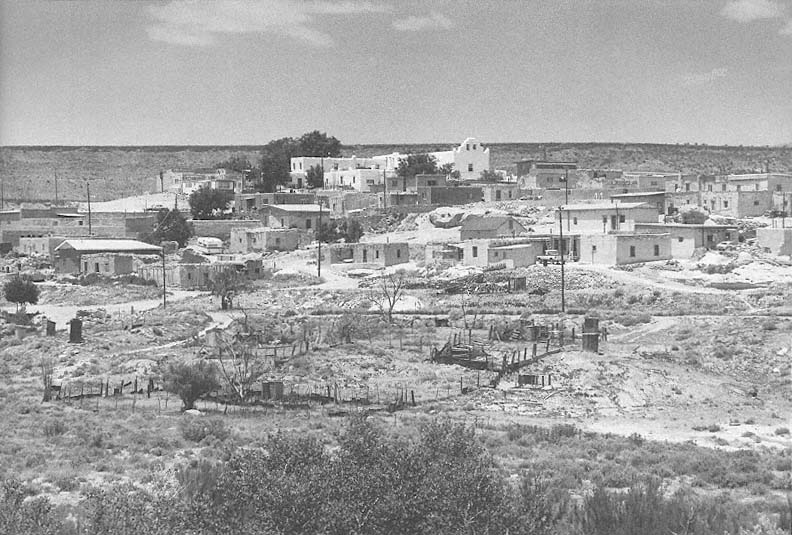

28–1

Laguna Pueblo

The white form of the church crowns the pueblo hillside.

[1984]

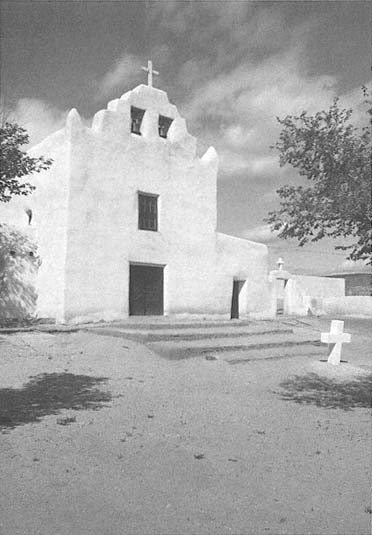

28–2

San José

The facade of San José and its campo santo.

[1986]

population at 174 Indian families with 600 persons and 20 families of citizens with 86 persons, which no doubt included the Spanish members of the congregation rather than only those living in the pueblo itself.[7] He also described the mission for the first time: "The church is small, the ornament poor."[8]

Sixteen years later Domínguez found everything "built here . . . made of stone from the hill and mud" and the church "very gloomy."[9] The walls of this simple church were "not very thick," the floor was bare earth, there were only "two poor windows with wooden gratings facing south, and another facing east," and the clerestory illuminated the interior.[10] The convento lay to the south. "Father Claramonte rebuilt all that has been mentioned in the year 1766, for when he came to this mission, he found everything in bad shape, and so he installed many doors and windows."[11] Domínguez showered rare praise on the cloister; "Although walled in, it is light, for when the said father rebuilt it, he arranged a beautiful window on each side."[12] The friar's quarters on the small second story were considered "very pretty," with a view over the cemetery. He also recorded the meager increase in population, now totaling 178 families comprising 699 persons.[13] In the early decades of the nineteenth century reconstruction was instigated under the direction of Fray Mariano Peñón.[14]

De Morfi mentioned nothing of the church structure itself but seemed favorably impressed by the visual aspect of the pueblo, which he saw as "one of the most beautiful which the entire realm has. It is situated on a hill of moulded rock which makes the flooring hard. Its rooms are well arranged and evenly made. The houses are all of stone, all two stories along the upper part, and well constructed. They are very clean and neat within and without, painted and whitened with enjarre similar to gypsum."[15] He also devoted about half his entry to the "abundance of snow" in winter, the "little stream fed by a spring" called El Gallo, "pleasing and crystalline water," and the small lake west of the pueblo.[16]

The whiteness of the pueblo and/or its church elicited continual notice from visitors. "Seen from the windows of the cars of the Atlantic and Pacific Rail Road whose track runs within 50 yards of the noble old wreck," wrote Bourke in 1881, "the white-washed walls suggest the idea of a beacon planted in the midst of a restless ocean of strife and angry passion."[17] In a landscape of earthen chroma, white can be as powerful as the sun whose light it reflects.

In descriptions of the social structure of Laguna,

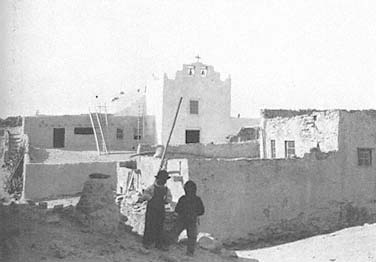

28–3

San José

circa 1917

The whiteness of San José has always distinguished the church from

the ruddy tones of the pueblo.

[Museum of New Mexico]

writers continually noted the tension caused by the presence of diverse social elements within the group. Their origin, for example, derived from the stock of several pueblo groups. Although the Laguna shared a common language with the Acoma, there was always some implicit conflict with their neighbors in the Sky City. In the late nineteenth century a progressive faction of the pueblo that followed Protestant, rather than Catholic, living patterns caused additional problems. In reaction, a group of the more conservative elements of the pueblo emigrated to Isleta pueblo, or nearby Mesita, in about 1879. The dissention was also directed at the church, and there had even been pressure from the Protestant-linked group to tear the building down. Its preservation is credited to the sacristan Hami:

His descendants tell of Hami debating the crisis, praying, bathing, washing his hair, putting on clean clothes, praying again . . . and then going to the dilapidated church which recently had been used as a corral for burros. Bracing himself in the doorway, he told the Protestant "progressive" crowd which had gathered outside that they could pull down the church only after they had first killed him, the sacristan. . . . Then he set himself to its repair.[18]

The challenge worked and the church remains.

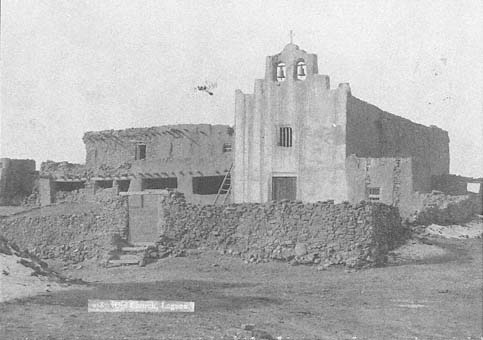

As the century closed Bourke found that the church, "once the seat of a convent and surrounded by monastic buildings now in the last stages of ruin, is itself in fair preservation."[19] The continuing dialectic of decay and repair continued into the twentieth century. During the 1920s Father Fridolin Schuster of Acoma could "announce joyfully that the work of placing a roof on the mission church . . . had been finally completed successfully."[20] As part of its work recording key structures during the Depression, the HABS measured and documented the Laguna church; the remodeling of the convento followed soon thereafter.

Today, not surprisingly, the pueblo has changed greatly. Prince listed the population in 1905 as 1,384 and in 1910 as 1,583, indicating that notwithstanding the perils of European contact, the pueblo has managed not only to hold its own but also to grow. Prince referred to the pueblo as "the most prosperous and progressive of Indian communities." But he qualified his remarks by adding that this progressive spirit had also fragmented the unity of the pueblo because "the people who were originally concentrated in the one town have become scattered in various communities in order to carry on their farming operations to better advantage. In consequence of this, the town is almost deserted in

28–4

San José

1885

The second story of the convento (left) still existed in the late nineteenth century.

[F. A. Nims, Museum of New Mexico]

28–5

San José

1895–1905

By the turn of the twentieth century, the second floor of the convento had almost completely

disintegrated, although the church and lower walls appear to have been well maintained.

[Museum of New Mexico]

28–6

San José, Plan

[Sources: Kubler, The Religious Architecture ,

based on HABS and field observations by

Stephen Glaudemans, Dorothée Imbert, and

Marc Treib, 1990]

the summer, and even in winter many of the old houses are vacant and going to ruin."[21]

What was already noticeable to Prince in 1915 has continued throughout the twentieth century and has been exacerbated by the federal government's policy of constructing more modern detached housing on the perimeter of the pueblo at the expense of the traditional plaza and core. Seen in Stubbs's aerial photographs of the pueblos published in 1950, the main dance plaza was divided in two sections by a block of houses, which are now gone, leaving the plaza as one space.[22] The church, although dominant in its position and color, sits to the side of the main plaza and with new development is further removed than it had once been.

San José de la Laguna is notable in several ways. On the top of the crest, it serves as a fitting crown to the hill and the land around it. The church was built with a single nave and battered apse. About twenty-three feet wide, the span indicates that the roof vigas came from mountain sources thirty miles distant. Above the vigas and particularly noticeable in the underside of the choir loft are the herringbone latillas beautifully articulated through painting in black, red, and white [Plate 9].

One enters the church through the walled burial ground, passing through a handsome gate topped by a pediment in the form of a stepped sky altar. The yard is bare except for one cross, which commemorates scores of graves left otherwise unmarked. There is only bare earth, terraced to effect a transition between the lower plane of entry and the floor level of the church itself. To the left is the convento structure, still present but reduced from the two-story buildings visible in nineteenth-century photographs. The facade, which recalls the old Santa Clara or Isleta as seen in earliest photographs, is planar, although it is enlivened by a stepped pediment flanked by two small towers at either edge. These recall the twin-towered form to which so many churches once aspired, while they also sensibly compensate for the increased erosion of the corners of the facade by wind and rain.

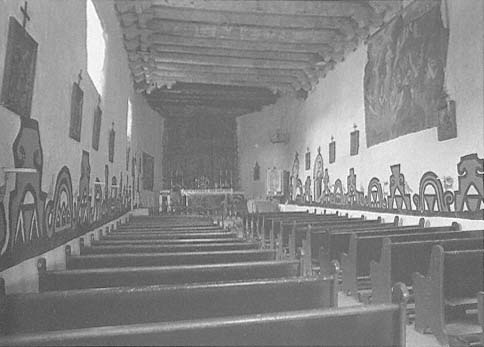

While the interior is dark, the clerestory having been covered up in subsequent remodelings, the nave is animated by color and ornamentation. The walls are painted with abstract geometric and bird designs in red and black that run along the length of the nave. The floor remains earthen, dry, and cracked and packed through use over centuries; in the sanctuary rugs cover the floor in the traditional manner. In his descriptions Domínguez commented on several occasions that the only real floors in the churches were the rugs or blankets laid down on the

28–7

San José

The painted ornamentation plays a significant role in completing the church architecture and

activating the edge between the wainscot and the upper wall.

[1981]

28–8

San José

Detail of the animated black and red painted ornament,

which mixes abstract, vegetal, and animistic motifs.

[1981]

28–9

San José

The church interior about 1935.

[T. Harmon Parkhurst, Museum of New Mexico]

altar floor and that these were often the property of the friars, either brought with them or traded or purchased from the Indians.

In addition to the wall paintings, which have the look of recent execution, the church possesses one of the finest altarpieces in New Mexico [Plate 10]. A portrait of Saint Joseph fills the center of the reredos. He is flanked on the right by Saint Barbara, protector against thunder, lightning, and sudden death, and on the left by Saint John Nepocene. Above the altar, projecting at an angle to it, is a panel painted with images from the native religion, that is, the moon, sun, rainbow, and stars. While suggesting native origins, this projection functionally serves to keep dust and dirt from the roof from falling on the altar. The entirety of the piece is so consistently painted and integrated that the seeming discontinuity in iconography is all but completely mitigated. As a whole, the decorations of the church convey the intensity with which the Indians undertook the decoration of the church, although the principal paintings were from the Laguna Santero.[23] In Laguna, perhaps more than in any of the other missions, decoration plays a central role in the feel of the building.

Although Acoma also features some wall paintings, their effect is limited by the immense volume of the nave. At Laguna the decoration is felt more strongly: in the painted wainscot, the reredos that fills and cramps the sanctuary, the blankets or rugs on the floor, the painted latillas, the carved beams of the choir loft, and the elaborate detailing of the corbels. Together, as a suite of decoration, these elements not only unify but also embellish the space and transcend the restricted confines of its physical dimensions and the pervasive darkness.

Prince related the curious story of the enmity caused by a painting of San José said to have been brought to Acoma by its missionary, Fray Ramírez, and given to him by Charles II.[24] The painting was reputed to have supernatural powers, and as a result, or so it was believed, Acoma had grown to prosper. Laguna shared none of Acoma's successes and was troubled by scanty harvests and periodic bouts with sickness and disease. San José was also the patron saint of Acoma—although the church there was dedicated to San Esteban—and Laguna pueblo asked to borrow the painting to effect a reversal in the village's fortunes. Acoma was less than anxious to let the painting go, and only after a season of penance and prayer instigated by the priest did the congregation agree to draw lots to "let God decide." God's decision was to have the painting remain on the mesa. So angered by the decision were the Laguna parishioners that a group of them broke into the Acoma church and took the painting back to their pueblo. Only with considerable difficulty and with persuasion by Father Mariano de Jesús López was conflict avoided, which finally convinced the Acoma people to be generous with the miraculous image.

Laguna's lot improved, which only added to the faith the Acoma people bestowed on the painting and to their considerable efforts to have it returned. But Laguna adamantly refused. Father Mariano personally talked to the Laguna parishioners at length, imploring them to see reason and acquiesce. But they would not. Finally, Acoma sought legal recourse, and the case reached the Supreme Court of New Mexico as the case of The Pueblo of Acoma v. the Pueblo of Laguna .

"All we know," Prince wrote, "is that it was hotly contested, and that the lawyers' fees made both pueblos poor." Judge Kirby Benedict decided in favor of Acoma and declared that the painting be returned to its rightful owners. A party from Acoma started out to reclaim the painting; halfway to Laguna, in the canyon that separates the two pueblos, the party found an image of San José "resting against a mesquite tree." Having heard the decision, the story concluded, the saint "was in such a hurry to get back to his home in Acoma that he started out by himself."[25] While the court case is a matter of record, the nature of the incident remains a mystery.