San Buenaventura

1659?–1660s

The pueblo of Las Humanas constituted the limit of culture in more than one sense. On the periphery of the Rio Grande pueblos, it was situated on the edge of a vast desert that supported only nomadic raiders. If the sky did not precisely "determine" in these lands, it certainly coerced. Water was measured by its absence, and existence was always marginal. And yet in spite of these severe environmental conditions, a community of several thousand people thrived until the Spanish arrival in New Mexico. This arrival also marked the beginning of a rapidly escalating population decline: about a century later the pueblo would be deserted.

Las Humanas, or Gran Quivira, is one of the three sites that today form the Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument. Salinas is Spanish for "salt beds", and these were the lands from which the salt so critical for the preservation and flavoring of food and for mining was extracted. From here it was shipped in trade to other parts of the province and to Mexico itself. The land, Lummis related, was not always salty. According to Indian myth, this area was once freshwater lakes, and it abounded with fish, waterfowl, bison, and antelope. But dwelling among the people was one unfaithful wife, "and for her sins the lakes were accursed to be salt forever."[1] Under the unyielding pressure of the heat of the sun, the seas evaporated, leaving the great salt flats east of the mountains.

The remains of Las Humanas pueblo are situated on a gentle rise in the rolling limestone hills that extend eastward from the base of the Chupadera Mesa. The road south from Mountainair continues through this sparsely settled landscape, and the monument is hardly discernible in the surrounding landscape. As one approaches, however, the regularity of San Buenaventura distinguishes it from the adjacent scrub and terrain. It has changed little since Adolph Bandelier wrote about it almost a century ago: "In this arid solitude the massive edifice of the church, with the mounds of the pueblo, look strangely impressive. From the west the church can be seen miles away, a clumsy parallelopiped of gray stone; from the northeast, through vistas of dark cedars and junipers, the ruins shine in pallid light, like some phantom city in the desert."[2]

Based on ceramic evidence, inhabitation on the site began some time between the seventh and eighth centuries, with A.D . 900 the latest probable date.[3] This fortuitous location formed a geographic pivot between the Jornada branch of the Mogollon culture to the south and the Rio Grande Anasazi culture to the west. Interpretation of pottery found during excavations determined that both cultures

27–1

Gran Quivira

The ruins of San Buenaventura are to the right, and San Ysidro is to the left.

[Fred Mang, Jr., National Park Service, early 1970s]

had a decided effect on the pueblo until the beginning of the fourteenth century, when the culture turned more decidedly toward the Rio Grande. The pueblo's language, like that of nearby Abo, was Tompiro. By the thirteenth century "pueblo groups of 12 or more surface buildings" had been built, with the pit dwellings of earlier eras being retained as the ceremonial kivas.[4] About seven miles west of the pueblo, wells fifteen to twenty-five feet deep provided a more reliable source of water.[5] The current average rainfall is only twelve and a half inches, most of it falling in irregular summer storms and incapable of being retained. But if water is present, the soil can be made to bear.

The group managed to thrive in spite of the severity of geographic and climatic conditions by augmenting agricultural subsistence through chasing deer, quail, bison, and rabbit and growing corn, squash, and beans—none of which required high water consumption.[6] In time geography played a decisive and in this case positive role, positioning Las Humanas as the last commercial outpost between the sedentary pueblo peoples and the nomadic Plains groups. Like Pecos, or to some degree Taos far to the north, Las Humanas became an important trading camp where the Plains Indians exchanged the products of the buffalo for the products of the soil. The pueblo's position, however, ultimately proved to be its downfall as drought and continued demands by nomadic traders for goods brought the pueblo to ruin.

Early Spanish exploration did not reach the Salinas district because the usual route turned north along the Rio Grande nearer present-day Albuquerque. Only with permanent settlement were efforts made to bring the Indians under Spanish hegemony and into the church. In October 1598 Oñate traveled through the country and found three Humano pueblos. In March 1599, Scholes reported, Oñate personally visited the provinces of Abo and Xumanas (the original spelling). Oñate wrote his superiors that he had again visited "the Xumas [sic ], where within four leagues there are three pueblos, one very large like Cia [Zia] and two smaller ones. [A]nd the two pueblos of the Salinas and the Xumanas all gave obedience to your majesty."[7]

The first friar to begin serious conversion work at the pueblo was Alonso de Benavides. Having preached a sermon in the plaza of the pueblo, he reported, "The Indians are all converted, the majority baptized, and more are being catechized and baptized every day."[8] Benavides explained that there were six churches and conventos operating in the district.

27–2

Gran Quivira

View over the pueblo toward the remains of San Buenaventura.

[Fred Mang, Jr., National Park Service, 1973]

27–3

San Ysidro

The first church seen from the exterior of its apse

[1986]

Among the pueblos of this nation there is a large one which must have three thousand souls; it is called Xumanas, because this nation often comes there to trade and barter. I came to convert it on the day of San Isidro, archbishop of Seville, in the year 1627, and I dedicated it to this saint on account of the great success that I experienced there on that day. Many were converted, and our Lord delivered me on that day, because these Indians are very cruel. Nevertheless, many leaders were converted, and with their favor, I erected the first cross in this place and we all adored it.[9]

In 1629 Father Francisco de Letrado arrived and is believed to have begun construction on the chapel of San Ysidro, which lies southwest of the main flank of the native structures. Exactly how much he completed during his tenure has not been determined, although Benavides credited him with the building of a church and convento. Archaeological evidence does not seem to bear this out, at least not to the letter, because no remains of a convento have been found in relation to the first chapel. The convento to which Benavides referred was probably a portion of the Indian pueblo that had been modified to provide a residence for the visiting priest, storage areas, and perhaps office space. Letrado left to minister to Zuñi in 1632, and for the next twenty-eight years Las Humanas remained a visita of Abo. The latter was a much larger pueblo—at least in the beginning—and was closer to the Spanish strength and farther from hostile nomad groups. A stream also provided Abo pueblo with an adequate amount of water, in contrast to the marginal and irregular sources of Las Humanas.

Ironically the first and "small" chapel of San Ysidro was among the widest of any New Mexican church, second only to the early construction of San José de Giusewa in the Jemez Mountains. Apparently even the priest supervising the building was not aware of this fact, nor did he possess the necessary knowledge of structure and construction. The span may have exceeded that allowed by the beams and the bearing capacity of the wall supporting them. The chapel, today in ruins, measured 29 feet by 109 feet, a considerable size for a first effort. Located on a falling limestone slope, part of the floor had to be built up and part excavated. Only in the eastern sections was a foundation wall laid, the remainder being built directly on the bedrock of the mesilla. Here, at the entrance (east) end, the walls were three and a half to four feet thick, while the remaining walls were kept between one and a half and two feet thick. (The stone walls at Quarai and Abo, for example, were at least three to four

27–4

San Ysidro, Plan

[Sources: Vivian, Gran Quivira ; and National Park

Service measured drawings, 1986]

27–5

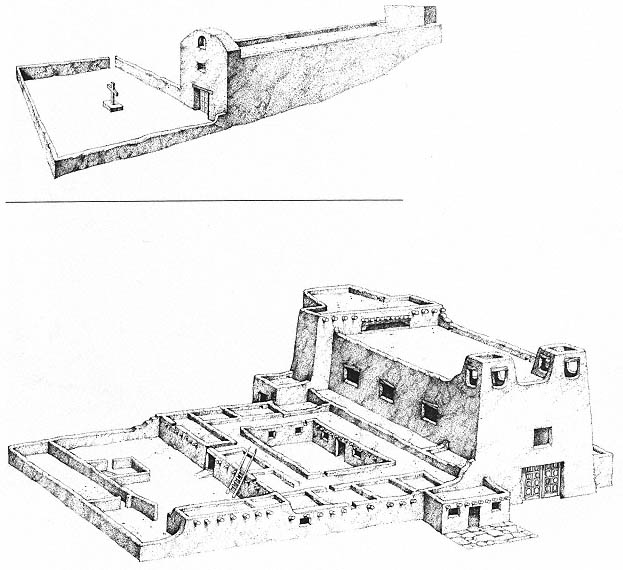

Gran Quivira, Hypothetical Restorations of San Ysidro (Above) and San Buenaventura (Below)

[Lawrence Ormsby]

27–6

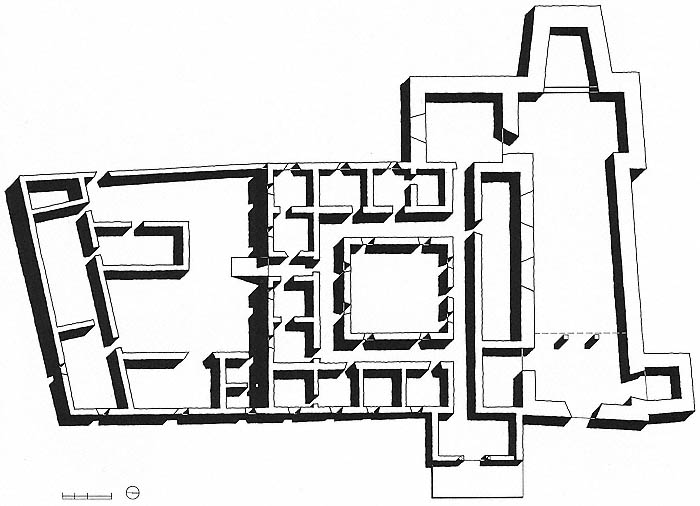

San Buenaventura and Convento, Plan

[Sources: Vivian, Gran Quivira ; and National Park Service measured drawings, 1983]

feet thick and could vary up to a full six feet in places. The system of buttresses at Abo allowed for the relative thinness of the walls.) At San Ysidro the minimal wall thickness courted disaster, and the width of the nave relative to its wall thickness has been offered as evidence that it was Letrado who began construction. If it had been Fray Francisco de Acevedo who supervised construction at Abo, he would have been far more knowledgeable, having had his own church as precedent, and would not have attempted the architectural daring—or ignorance—that transpired at Humanas.

San Ysidro is of the single-nave type without transepts and is oriented on an east-west axis. It was constructed of the local light blue-gray limestone, unworked, but positioned best side out [Plate 5]. The stones were set in a mud mortar, or caliche . Along the nave are two rows of what are taken to be foundation stones; Gordon Vivian interpreted these to be the bases of a row of columns that supported the roof beams.[10] Although these posts might have been intended from the start of construction, in effect forming a three-aisle church, they were probably, introduced once the bearing capacity of the walls or the strength of the beams had been tested and found wanting. The pines for the great vigas, which must have been at least thirty-three feet long, could have come only from the Gallinas Mountains at least twenty miles away and were probably positioned on seven-and-a-half-foot centers. On top of these were savinos of the local juniper, used when the span presented no problem. The usual layer of branches topped the construction, carrying the adobe mud for the roof surface. The weight of this building system was considerable and paired with the relative thinness of the walls hastened the collapse of the structure after the pueblo was abandoned in 1670. In the eastern portion of the nave the foundation stones supported columns that carried the choir loft located just inside the entry.

Not much is known about the chapel's fenestration. There were probably one or two high windows in the south wall, a common pattern, but whether there was also a clerestory is impossible to determine because the existing walls are too low for a definitive interpretation. Vivian believed that oiled sheepskin parchment covered the windows because it more easily fit into the window frames than the irregular pieces of selenite of the native tradition.[11] Throughout the centuries tales of buried wealth attached to Gran Quivira (hence its sobriquet), and treasure hunters hastened the natural processes of attrition with their forays and their digging. The floor and altar area of the San Ysidro

27–7

San Buenaventura

The nave of the church, with tapering apse and two shallow transepts

[1984]

chapel were particularly unfortunate victims of such searches.

The altar end of the church still contains the remains of the stone altar and a box believed to have held the vessels of baptism. The font itself was supported on a small stand, the fragments of which lie along the east wall near the choir loft. Remnants of a thin, sandy plaster reveal that the interior of the nave was plastered. Along the base of the wall a wainscot of dull red paint once existed, decorated above a thin black line with designs painted on the white plaster. Similar treatment may be seen today at Acoma and Laguna. Only small fragments of these decorations have been found, however, implying that at least a portion, if not all, of the nave was so decorated.

West of the church's simple planar facade lies the burial ground, which is surrounded by a low stone wall and is focused on a single cross set on a stone base. Like the later San Buenaventura, the stone wall of the church might have been integrated into the circumferential wall of defense around the pueblo.[12]

San Ysidro represents a common second stage in mission development: the extension of development efforts from the existing spaces of the pueblo (first stage) to a small, temporary church for use until a larger structure was warranted. Single-nave buildings of the same type as San Ysidro include one at Tabira (1629), the earliest chapel of San Miguel in Santa Fe, and the "lost" Pecos church from the first two decades of the 1600s.[13] The church of San Buenaventura illustrates the third phase of mission establishments in the New Mexican religious campaigns: substantial edifices meant to endure.

Given the location of Las Humanas in the marginal areas of Pueblo culture, it is difficult to explain why a church this large could have proven insufficient. Rather than increased needs, the deterioration of the existing chapel or the desire for a less marginal position could have instigated the construction of a more ambitious edifice to the west of the old San Ysidro. The population already had seriously declined by the 1660s, perhaps by as much as fifty percent, from the 1627 count of 2,000 people.

During the 1650s the Apache raided the pueblo, destroyed the church, and carried off seventeen women and children as captives.[14] In 1659 Fray Diego de Santander arrived at Las Humanas, found the existing chapel in poor repair—perhaps in ruins—and began construction of the church and convento of San Buenaventura. These structures were still incomplete at the time of his departure three years later, although he is usually assigned credit for their erection.[15]

Gran Quivira witnessed one of the most exaggerated conflicts between the civil and the religious powers in New Mexico's history. Until Santander began his residency, Las Humanas had been administered from Abo. Nicolás de Aguilar, the alcalde mayor , came to the pueblo in the 1660s as a loyal executor of Governor Bernardo López de Mendizábal. Mendizábal had no love for the church, a fact borne out by his continuing program of personal gain at the expense of the religious venture. As Santander was trying to reestablish the position of the church in the pueblo, Mendizábal was waging a campaign against the religious by forbidding the Indians to work on the church's construction. The governor, Charles Hackett noted, "commanded under penalty of death that no Indian work on the structure; but the Indians continued at great risk in the construction of the edifice, for they had no church."[16]

This proscription was fueled by the traditional enmity between the missionaries and the governor's office. Indians working on construction could not be tending flocks, weaving, or growing corn. And if crops and other goods were produced for the religious, the friars were accumulating wealth directly in competition with the governor. The father replied to the governor that a church was needed to bring the word of God to the Indians. Unconvinced about such expenditures of time and resources, the governor replied "that churches with costly ornaments and decoration were not necessary; that a few huts of straw and some cloth ornaments, with spoken masses, were ample."[17] Construction continued, no doubt under the disgusted eye of Aguilar, who kept the governor informed of the pueblo's affairs.

Although the width of San Buenaventura is less than that of its predecessor, almost every other aspect surpassed the earlier structure. The nave is about 27 feet wide, with a length of 109 feet. There are two transepts barely 6 feet in average depth that hardly alter the impression of a single-naved church. The transepts are more symbolic than perceptual, although even these slight extensions allow for use as side altars. Like San Ysidro, the church is aligned on an east-west axis, with entrance again to the east. The original campo santo must have served for burials, as none fronts the second church.[18]

The construction technique remained the same: walls of local limestone laid in mud mortar but this time worked to a wall thickness of five feet or more.

27–8

San Buenaventura

The convento, its first courtyard seen in the center (walls with window openings) [1986]

The facade was planar and showed no traces of towers, although the remaining stone walls seen today offer that impression. A central door led directly into the nave through a tapered entrance spanned by a composite wooden lintel. The baptistry lay just to the right of the entry.

Evidence indicates that the building was never finished, although portions of its wooden structure had been installed, including the choir loft at the east end of the nave. This "entablature," as Major Carleton referred to it in 1853, received considerable carving and detail, but the church was never roofed.

Ornamentation, the last stage in the construction of a church, indicates that the edifice was nearly completed, although the corbels and beams were carved prior to installation. Because the span was shorter than San Ysidro's, vigas spared from the Apache desecrations could have been used in roofing the new church. Carleton was clearly impressed by the quality and the amount of carved ornamentation:

Some of the beams which sustained it [the choir loft], and the remains of the two pillars that stood along under the end of it which was nearest to the altar are still here; the beams in a tolerable good state of preservation—the pillars very much decayed; they are of pine wood, and are very elaborately carved. There is also what perhaps might be termed an entablature supporting each side of the gallery, and deeply embedded in the main wall of the church; this is twenty-four feet long, by, say eighteen inches or two feet in width; it is carved very beautifully indeed, and exhibits not only the greatest skill in the use of various kinds of tools, but exquisite taste on the part of the workmen in the construction of the figures.[19]

The illumination of the church presents other problems of interpretation. Vivian, after Kubler, assumed that there was the typical window illuminating the choir loft from the east as well as one or more windows high on the south side of the nave.[20] The existence of a clerestory cannot be definitely determined by archaeological evidence, although transept-type churches from this time usually possessed a transverse clerestory.

Along with the church, Gran Quivira now boasted a developed support structure. The extensive convento south of the church included a full sacristy with access from the south transept and a complete quadrangle of living and utility spaces. Lying further south was a large corral measuring sixty by fifty-three feet and an adjoining stable area. As the pueblo declined, the mission flocks and herds were moved to Abo, where food and water were more plentiful and the Apache slightly less in evidence.

By the middle of the 1660s conditions had turned even worse. As early as 1663 Alcalde Nicolás de Aguilar had sympathetically reported that "it costs a great deal to get water and it makes a lot of work for the Indians in obtaining it, and the wells are exhausted and there is an insufficient water supply for the people, for their lack of water is so great that they are accustomed to save their urine to water the land and to build walls."[21] The population fell to about one thousand. During the end of the decade no crops were harvested, and starvation became another of the population's miseries: at Las Humanas at least four hundred fifty people died. Those who did not die were seriously weakened and more prone to contract or expire from disease. Fray Juan Bernal, writing in 1669, described the horrible scene of the great number of Indians "lying dead along the roads, in the ravines, and in their huts."[22]

Conditions were no better for the Apache. What had been denied them through trading, they now attempted to extort through attack and theft. But there was little left to steal, except perhaps human life, which could be sold into slavery in exchange for life's necessities. The Apache displayed their rage by destroying the church on September 3, 1670. The situation had become intolerable. In either 1671 or 1672 the pueblo was finally abandoned to the desert, the Apache, and, in time, the Anglos.[23]

The site had sporadic visitors over the centuries. At the time of Major Carleton's visit in 1853, the ruins of the churches were still visible. The pueblo itself had been transformed into a series of earth-covered mounds, only parts of which have yet been excavated. Tales of buried treasure still brought many seekers, and even after the transformation of the site into a national monument in this century, permits were granted for digging. No treasure was ever found.

More scientifically, the School of American Research and the Museum of New Mexico undertook excavations of San Buenaventura commencing in July 1923 under the direction of Edgar L. Hewett. In 1951 National Park Service archaeologist R. Gordon Vivian undertook excavations at Gran Quivira that provided a more complete picture of the chapel of San Ysidro as well as parts of the pueblo proper. Gran Quivira National Monument was established on November 1, 1909; in the fall of 1988 it was incorporated with Abo and Quarai as Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument.