Abo:

San Gregorio

(1629–1644), abandoned by 1678

New Mexico, the Land of Enchantment, presents several mysteries of settlement that continue unanswered.[1] One of these is the precise reason for the Pueblo settlement of the Salinas plains. The barren land is hardly conducive to burgeoning ranchos and villages, water is relatively scarce, and there is little prominent indigenous vegetation besides the stubby Utah juniper and Rocky Mountain cedar. The reason for Spanish settlement in the valley is more easily answered: the Indians were already living there. Abo, for example, was a thriving community of nearly two thousand inhabitants at the time of the Spanish colonization in 1598. The pueblo managed to extract a satisfactory subsistence from the inhospitable soil and the nuts of the piñon tree, although there was little rainfall or groundwater for irrigation. A small stream south of the pueblo flowed intermittently throughout the year. Joseph Toulouse described the weather, somewhat understatedly, as "sub-humid with a deficiency of moisture all year round."[2] Neither of the mountains nor of a river drainage, "Abo is in the transition zone here identified as Grassland"[3] —a small pad of level ground between the Manzano Mountains to the northwest and the Great Plains to the east.

The native population that settled here at the end of the eleventh century belonged to the Tompiro group, the mountain relatives of the Piro who lived to the south. The pueblo occupied a large parallelogram roughly a thousand feet on its long side and three hundred feet in width and was encircled with a "strong, continuous fortification with only one entrance."[4] The strong wall was a necessity: on the very edge of the pueblo culture, the community was constantly exposed to attack from the marauding Indians of the Plains, one of the factors that led to the eventual destruction and desertion of the villages. The Salinas missions, perched as they were on the delicate edge between existence and dissolution, have been referred to collectively as the "Cities That Died of Fear,"[5] an extreme instance of the problems that beset the Pueblo people as a whole.

Coronado never reached these lands east of the Manzanos; his turning point northward was the Galisteo basin that skirts the Salinas district to the north. Oñate's expedition pivoted at about the same place, and in his stead he sent a small party eastward under the direction of his nephews and lieutenants Juan and Vicente de Zaldívar. They found the pueblo active and thriving, a description difficult to believe in view of subsequent events. When the Spanish colony was established in 1598, the missionaries were assigned custody of the various Indian settlements, and the Salinas missions were

25–1

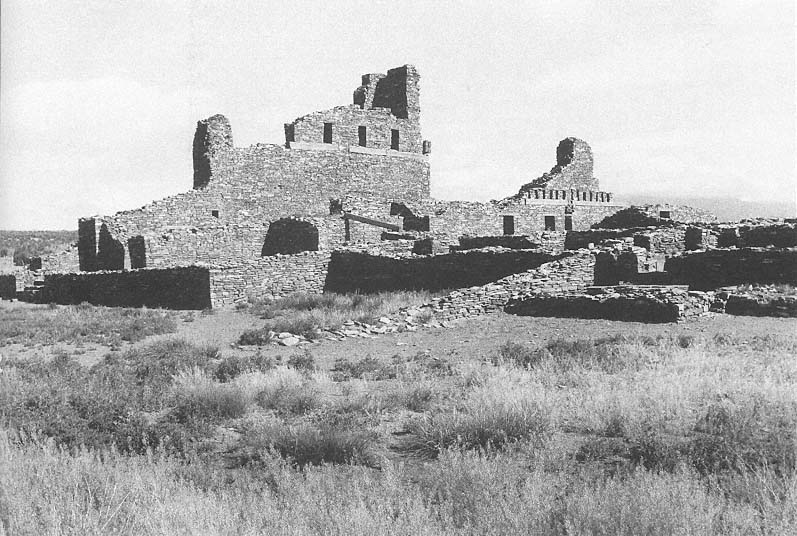

San Gregorio

View over the convento ruins toward the nave. The recesses in the upper part of the nave walls suggest the stacked

beams they once supported.

[Fred Mang, Jr., National Park Service, 1973]

administered as a single group. Fray Francisco de San Miguel, based at Pecos to the north, assumed jurisdiction over the Salinas efforts but accomplished little: the distances were too great and the available resources too meager. Only in 1626 when Fray Alonso de Benavides acquired charge of the Custody of the Conversion of Saint Paul, which administered evangelical efforts in New Mexico, were the first positive results registered. He was succeeded by Fray Alonso de Peinado, who brought additional priests and supplies in 1609–1610; it was he was established the first permanent mission in the province, at Chilili, around 1614.

Benavides listed Fray Francisco Fonte as "guardián de Abo" until 1635, but it was the arrival of Fray Francisco de Acevedo in 1629, and his subsequent stay at Abo of more than a decade, that marked the first decisive missionary efforts and architectural realization. Fray Francisco "undoubtedly played an important part in the construction of the church whose ruins we see today."[6] He chose Abo as his headquarters based on the substantial size of the community and the available resources. Prior to Spanish contact the Indians lived primarily by subsistence agriculture. The export of piñon nuts, and salt—a commodity precious to the Spanish for mining as well as preserving food—led to a limited economic prosperity for the community, which was able to acquire an organ for the choir loft some years later. After 1630 Las Humanas (Gran Quivira) and Quarai were made visitas of the more prosperous Abo. The church is said to have been named for Åbo, Finland (now Turku), and for its patron, Saint Gregory. This claim is probably fatuous because an Indian village by the name of Abo, on or near the site, existed before the Spanish arrival.[7] The Spanish may, however, have taken a near-phonetic rendition of the Indian term and associated it with the name of one of their known saints.

The construction of the mission complex extended over its entire history of almost half a century. Religious and physical necessity played a significant part in prompting the continuing building program. Recent excavations and study by James E. Ivey, archaeologist and historian with the National Park Service, ascertained that the history of San Gregorio had three major stages. In the first phase, dating roughly from the middle to the end of the 1620s, a convento with a single courtyard was constructed contemporaneously with the first church. This was a simple structure with a single nave terminating in a square apse similar to the church of San Ysidro at Gran Quivira or the earlier form of San Miguel in Santa Fe. Built of stone and set on an

25–2

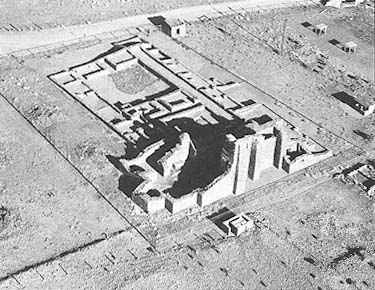

San Gregorio

Aerial view of the church and convento ruins.

[Fred Mang, Jr., National Park Service, 1975]

earthen and rubble platform, the church was probably plastered on both the interior and exterior and utilized clerestory lighting. It maintained this form for about twenty years.

Franciscan building programs during the seventeenth century expressed far greater ambitions than those accompanying the Spanish return in the 1690s. The mission churches were intended as structures of magnificence, and until time and resources ran out, building projects almost continually augmented existing structures.

From 1645 to 1649, the second phase, San Gregorio underwent a massive renovation, but it did not follow the somewhat typical pattern of mission development, which began with the rooms of the pueblo, then extended to a small church as a temporary measure, and thereafter culminated in an edifice worthy of the Catholic venture. (The sequence at Gran Quivira illustrates this pattern.) Under the direction of Francisco de Acevedo, the apse end of the old church was demolished to allow for an extension of the nave toward the north. New east and west transepts and an apse in battered form completed the existing structure, which was retained in the renovated church. The convento was also refurbished at this time. The roof was raised, and new walls were thickened to address structural demands placed on them. To strengthen the thinner walls of the first church, buttresses were added.

Although pressures against the Salinas mission group were increasing, in the mid-1650s, the third phase, a reinvigorated effort was mounted to strengthen the religious and economic program. The convento was again rebuilt, and a second courtyard was added primarily for storage and animals; and pens and corrals were constructed to complete the building program. But within ten years the pueblo and the mission would be left untended.

The church building was positioned in the northeast corner of the pueblo on about the only piece of land available for construction. Even in this relatively flat location the land fell in places, and a level floor could be attained only by adding fill to the chapel and convento areas. The mission and its entry faced south, with the sole means of access through the pueblo proper. Here fear joined the Spanish and the Indians in a common bond against Apache raiders.

San Gregorio is a continuous-nave church, although there are two vestigial transepts two-thirds of the way along its length. While not fully developed as transepts, they are a definite inflection to the hall and define the transition to the chancel area

25–3

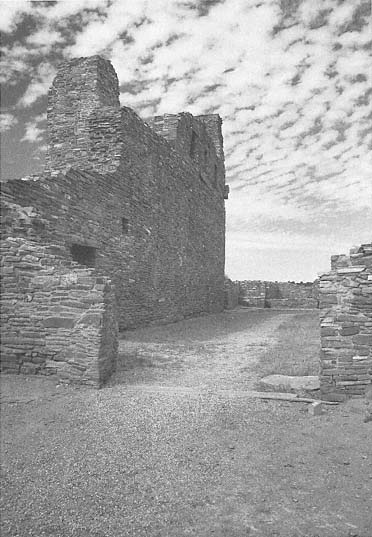

San Gregorio

The use of buttresses to stiffen the walls of the nave allowed for a

reduction in wall thickness.

[Paul Logsdon, mid-1980s]

25–4

San Gregorio, Plan with Convento

[Sources: Toulouse, The Mission of San Gregorio ; and National Park Service measured drawings]

to the north. The nave was built to commodious dimensions, roughly one hundred thirty-two feet in length and in width from about twenty-three feet at the south entrance to almost thirty-two feet at the end of the sanctuary. The nave's walls are almost parallel, which seems to refute Kubler's theory that the nonparallel relation of nave walls in New Mexican churches might have been consistently intended to make the spaces seem longer through optical illusion.[8] Any discernible impact on perception at Abo would work against this intended effect. The church was almost fifty feet in height, and with the exception of today's San Esteban at Acoma, it would have been roughly twice the height of any of the state's existing adobe churches.

On the south a narthex was formed by the extended east and west buttress of the entry facade, and to the right of the main doors a small chapel shared a terrace with the narthex. As a solution to the problem of accommodating the vast population of Abo, the campo santo might have been used in the manner of an atrio, the memory of which was fresh in the minds of the recently transplanted friars. This structure, unlike much of the construction at Abo, was made of adobe, and it is possible that this chapel was used to conduct services during the construction of the church. Until about 1640 an area below the choir loft served as the baptistry, but thereafter a new room was built to the left just inside the entrance. The sacristy, to the right or east, gave onto the sanctuary area, which was raised the typical several steps. Unlike its predecessor, the apse itself was battered inward and turned at a slight angle to the axis of the nave.

San Gregorio was constructed of sandstone, a reflection of earlier Indian building techniques. The area around Abo rests on a geological base of reddish-brown sandstone, a stone already fissured in layers and easily removed without iron technology. In driving to the church today, for example, one can see an eroded bluff cut by the nearby stream that exposes usable building material. Although the walls were to be plastered, the stone that faced the rubble core was selected and positioned to reduce irregularities in the wall surface. The stones, which were rarely larger than one foot square or more than four inches thick, were laid up dry or set in adobe mortar for stabilization. Smaller fragments could be inserted as chinks into the gaps left by stones of irregular profile. As Carleton claimed in 1853, "We saw not a single dressed stone about the ruins."[9] Although stones were not dressed, the smoothest side was usually oriented outward. The construction method was analogous to that used during the

25–5

San Gregorio

The nave and remaining portions of its west wall.

[1986]

tenth through thirteenth centuries at the various hamlets in Chaco Canyon.

Although stone is more permanent than adobe, construction time could be considerably longer. In addition to permanence, stone construction required water only for mixing the adobe mortar. Stone also permitted greater wall heights than adobe, which rarely rose above thirty feet. The walls at Abo were remarkably thin—about three to four feet—and were relatively consistent in thickness throughout the church. Buttresses provided additional strength when needed to support the clerestory beams, for example, and a number of engaged external pilasters remain clearly visible on the western side. At the corners, under the bell tower, and in the buttresses an additional mass of five or more feet in thickness stabilized the weight and thrust of the beams. With this system, which drew upon the fortified church of Spain transmitted through Mexico, the celebrants were able to build a structure of considerable dimensions using reasonable quantities of materials.

The ceiling was beamed but did not use round vigas in the more typical manner. Six squared timbers, roughly one foot by one foot in section, were bundled in groups stacked two wide and three deep. Drawing on written sources, Edgar Hewett claimed that "the beams are said to have been the most beautifully carved and most massive in the southwest."[10] On top of the vigas were the smaller savinos, in turn covered by juniper and piñon branches and then thick adobe mud. The mud-plastered roof drained to the west away from the convento. This spanning system, rather than the arches more common in Mexico, reduced the problems of thrust against the side walls and allowed a reduction in mass—hence thinner walls. Had the walls of the nave been splayed, they would also have reinforced the rigidity of the structure, although in comparison to the dead weight of the stone buttresses, this contribution would probably have been negligible. In suggested reconstructions the parapet of the nave walls is usually shown as crenellated, adding to the image of the church as a fortified structure.[11]

The increased height of the transepts, eight feet higher than the nave, allowed for the clerestory's southern orientation, which offered a continuous flow of light throughout the day. The exact height of the roof over the apse is assumed to have been equal to that of the transepts. In the chancel are the remains of three stone altars, all facing north. A choir loft spanned the southern end of the nave. The interior of the church shows remnants of the white gypsum plaster applied to the interior walls.

25–6

San Gregorio

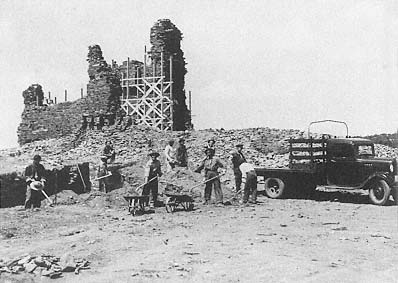

1938

Excavation and stabilization work in progress.

[Museum of New Mexico]

In some places there are also vestiges of black painted dados, which added to the sense of decoration. Doorways were cut into the walls using wooden lintels rather than arches. The floors were all packed adobe.

East of the church was an extensive convento, one of the largest in New Mexico, organized around two courtyards. Portions of the convento were constructed of adobe, and the floors in many areas were paved with sandstone flags. The "western court is surrounded by corridors into which open living quarters, kitchen storage rooms, and a room set aside for bird pens."[12] In the western courtyard a kiva was built slightly off center, possibly dating from the same time as the church. James Ivey suggested that it had been built with Franciscan approval as a transitional form.[13] It was used as a refuse pit for the convento during later Spanish occupation. The eastern courtyard was used for the friars' livestock, mainly sheep and goats, as well as for storage of goods. The entry doors to the church pivoted on iron pins, which Toulouse claimed to be the only instance of this type found in seventeenth-century New Mexico[14] —although wooden versions of the pivot were in use up to the construction of the Santuario at Chimayo in 1816. Other iron elements, which were necessarily imported from New Spain, were nails, hinges, buttons, and fire tongs, all of which appeared on the list of supposed provisions for the founding of new missions.

The admission of the Spanish into the precincts of the pueblo had the effect of a Trojan horse. Prosperity at first increased through export and trade, but material gain was more than offset by increased attacks by the Plains Indians who fed so viciously on the well-being of the pueblos. Communicable diseases, unknowingly injected into the mainstream through contact with Europeans, also contributed to the downfall of the Tompiro. And then in the late 1660s and 1670s drought and consequent famine attacked the tottering population, whose numbers dwindled quickly. As early as 1671 there were reports of emigration from Abo to the Rio Grande valley near Socorro, and by 1678 the formerly thriving pueblo was vacant and quiet. Only the wind and the Apache visited it. The former, with the infrequent rain, contributed to the erosion of the mission, while the latter probably burned down the church shortly after its abandonment. Excavations of charred timbers bore witness to this supposition.

From about 1800 to 1815 tentative efforts were made to resettle the area around Abo. Houses and utility buildings such as barns, corrals, and pens were constructed for dwelling, ranching, and farming. But these attempts were premature, and heightened Apache raids around 1830 forced the abandonment of the hamlet.

Although known, the Salinas sites were rarely visited thereafter. In December 1853 Major James Carleton, stationed at Albuquerque, took a tour of the Salinas missions and left a detailed description of how they stood at the time. He noted basic dimensions and indicated that there were no finished stones and that the woodwork had been destroyed by fire.[15] Fellow soldier Lieutenant Emory had left a picturesque but somewhat vague record of the ruins in 1848. The site became private property with the American occupation of the territory. Late in the century, with the Plains Indian threat gradually reduced, the land again provided for Hispanic habitation. This time resettlement efforts were successful, and for half a century the Cisneros family held and worked the land around the former mission.

In 1937 the University of New Mexico, already sporting a Spanish Colonial Territorial Revival campus, bought the property and held it jointly with the School of American Research. In 1938 the remainder of the site, on which the apse was located, was donated by Fred Cisneros, and the church buildings became a state monument. From June to December 1938 there were excavations and stabilizations on the site, work that continued through 1939. Late in 1981 the entire property, with Gran Quivira and Quarai, became a joint historical district known as the Salinas National Monument, administered by the National Park Service. In 1988 the name was modified to the Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument.