THE SALINAS GROUP

Abo:

San Gregorio

(1629–1644), abandoned by 1678

New Mexico, the Land of Enchantment, presents several mysteries of settlement that continue unanswered.[1] One of these is the precise reason for the Pueblo settlement of the Salinas plains. The barren land is hardly conducive to burgeoning ranchos and villages, water is relatively scarce, and there is little prominent indigenous vegetation besides the stubby Utah juniper and Rocky Mountain cedar. The reason for Spanish settlement in the valley is more easily answered: the Indians were already living there. Abo, for example, was a thriving community of nearly two thousand inhabitants at the time of the Spanish colonization in 1598. The pueblo managed to extract a satisfactory subsistence from the inhospitable soil and the nuts of the piñon tree, although there was little rainfall or groundwater for irrigation. A small stream south of the pueblo flowed intermittently throughout the year. Joseph Toulouse described the weather, somewhat understatedly, as "sub-humid with a deficiency of moisture all year round."[2] Neither of the mountains nor of a river drainage, "Abo is in the transition zone here identified as Grassland"[3] —a small pad of level ground between the Manzano Mountains to the northwest and the Great Plains to the east.

The native population that settled here at the end of the eleventh century belonged to the Tompiro group, the mountain relatives of the Piro who lived to the south. The pueblo occupied a large parallelogram roughly a thousand feet on its long side and three hundred feet in width and was encircled with a "strong, continuous fortification with only one entrance."[4] The strong wall was a necessity: on the very edge of the pueblo culture, the community was constantly exposed to attack from the marauding Indians of the Plains, one of the factors that led to the eventual destruction and desertion of the villages. The Salinas missions, perched as they were on the delicate edge between existence and dissolution, have been referred to collectively as the "Cities That Died of Fear,"[5] an extreme instance of the problems that beset the Pueblo people as a whole.

Coronado never reached these lands east of the Manzanos; his turning point northward was the Galisteo basin that skirts the Salinas district to the north. Oñate's expedition pivoted at about the same place, and in his stead he sent a small party eastward under the direction of his nephews and lieutenants Juan and Vicente de Zaldívar. They found the pueblo active and thriving, a description difficult to believe in view of subsequent events. When the Spanish colony was established in 1598, the missionaries were assigned custody of the various Indian settlements, and the Salinas missions were

25–1

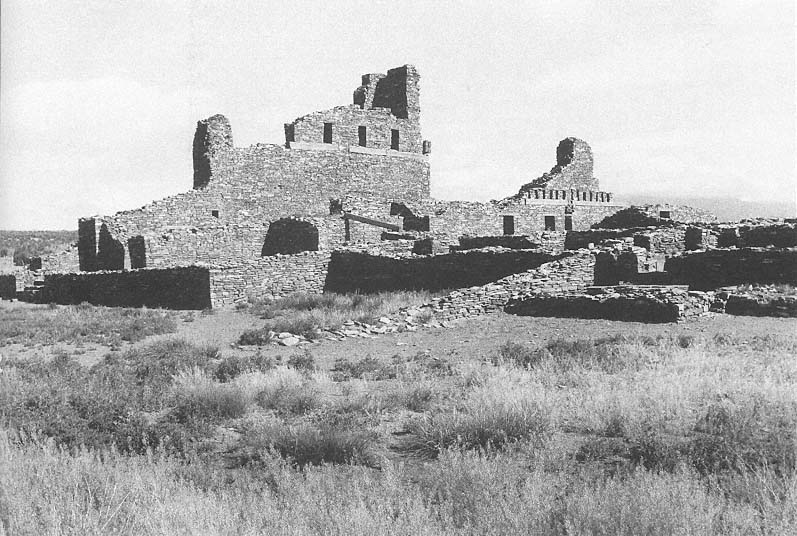

San Gregorio

View over the convento ruins toward the nave. The recesses in the upper part of the nave walls suggest the stacked

beams they once supported.

[Fred Mang, Jr., National Park Service, 1973]

administered as a single group. Fray Francisco de San Miguel, based at Pecos to the north, assumed jurisdiction over the Salinas efforts but accomplished little: the distances were too great and the available resources too meager. Only in 1626 when Fray Alonso de Benavides acquired charge of the Custody of the Conversion of Saint Paul, which administered evangelical efforts in New Mexico, were the first positive results registered. He was succeeded by Fray Alonso de Peinado, who brought additional priests and supplies in 1609–1610; it was he was established the first permanent mission in the province, at Chilili, around 1614.

Benavides listed Fray Francisco Fonte as "guardián de Abo" until 1635, but it was the arrival of Fray Francisco de Acevedo in 1629, and his subsequent stay at Abo of more than a decade, that marked the first decisive missionary efforts and architectural realization. Fray Francisco "undoubtedly played an important part in the construction of the church whose ruins we see today."[6] He chose Abo as his headquarters based on the substantial size of the community and the available resources. Prior to Spanish contact the Indians lived primarily by subsistence agriculture. The export of piñon nuts, and salt—a commodity precious to the Spanish for mining as well as preserving food—led to a limited economic prosperity for the community, which was able to acquire an organ for the choir loft some years later. After 1630 Las Humanas (Gran Quivira) and Quarai were made visitas of the more prosperous Abo. The church is said to have been named for Åbo, Finland (now Turku), and for its patron, Saint Gregory. This claim is probably fatuous because an Indian village by the name of Abo, on or near the site, existed before the Spanish arrival.[7] The Spanish may, however, have taken a near-phonetic rendition of the Indian term and associated it with the name of one of their known saints.

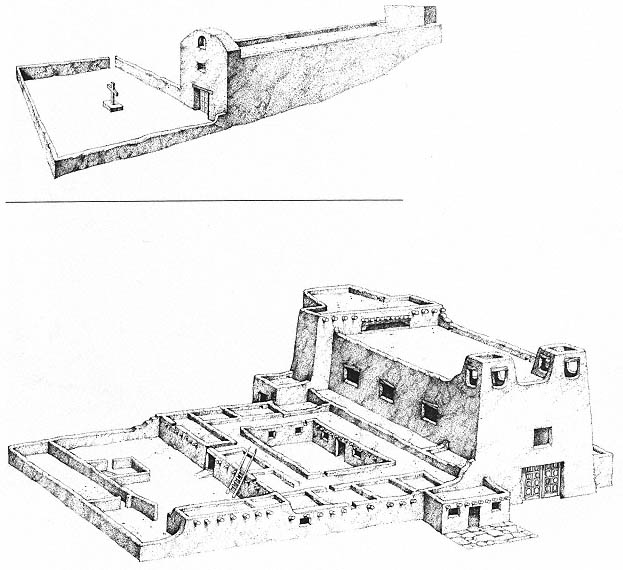

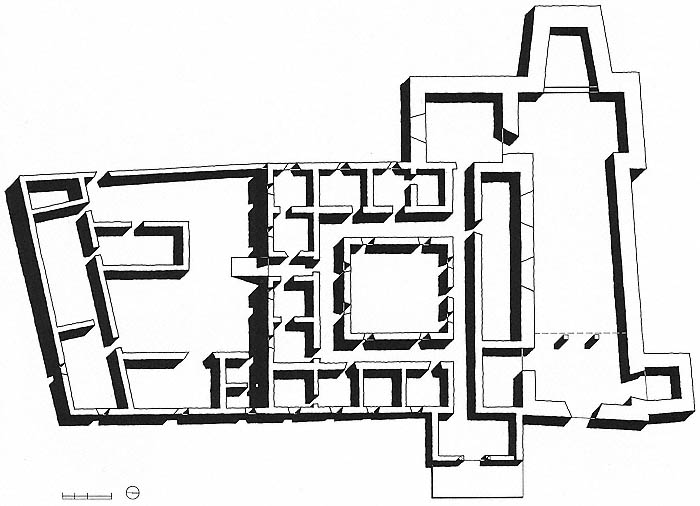

The construction of the mission complex extended over its entire history of almost half a century. Religious and physical necessity played a significant part in prompting the continuing building program. Recent excavations and study by James E. Ivey, archaeologist and historian with the National Park Service, ascertained that the history of San Gregorio had three major stages. In the first phase, dating roughly from the middle to the end of the 1620s, a convento with a single courtyard was constructed contemporaneously with the first church. This was a simple structure with a single nave terminating in a square apse similar to the church of San Ysidro at Gran Quivira or the earlier form of San Miguel in Santa Fe. Built of stone and set on an

25–2

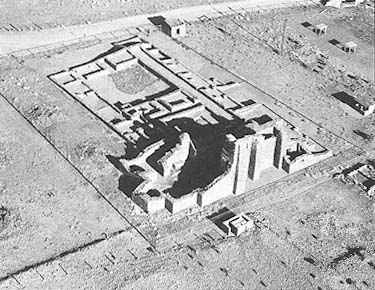

San Gregorio

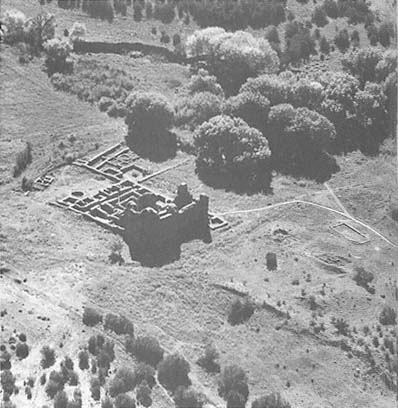

Aerial view of the church and convento ruins.

[Fred Mang, Jr., National Park Service, 1975]

earthen and rubble platform, the church was probably plastered on both the interior and exterior and utilized clerestory lighting. It maintained this form for about twenty years.

Franciscan building programs during the seventeenth century expressed far greater ambitions than those accompanying the Spanish return in the 1690s. The mission churches were intended as structures of magnificence, and until time and resources ran out, building projects almost continually augmented existing structures.

From 1645 to 1649, the second phase, San Gregorio underwent a massive renovation, but it did not follow the somewhat typical pattern of mission development, which began with the rooms of the pueblo, then extended to a small church as a temporary measure, and thereafter culminated in an edifice worthy of the Catholic venture. (The sequence at Gran Quivira illustrates this pattern.) Under the direction of Francisco de Acevedo, the apse end of the old church was demolished to allow for an extension of the nave toward the north. New east and west transepts and an apse in battered form completed the existing structure, which was retained in the renovated church. The convento was also refurbished at this time. The roof was raised, and new walls were thickened to address structural demands placed on them. To strengthen the thinner walls of the first church, buttresses were added.

Although pressures against the Salinas mission group were increasing, in the mid-1650s, the third phase, a reinvigorated effort was mounted to strengthen the religious and economic program. The convento was again rebuilt, and a second courtyard was added primarily for storage and animals; and pens and corrals were constructed to complete the building program. But within ten years the pueblo and the mission would be left untended.

The church building was positioned in the northeast corner of the pueblo on about the only piece of land available for construction. Even in this relatively flat location the land fell in places, and a level floor could be attained only by adding fill to the chapel and convento areas. The mission and its entry faced south, with the sole means of access through the pueblo proper. Here fear joined the Spanish and the Indians in a common bond against Apache raiders.

San Gregorio is a continuous-nave church, although there are two vestigial transepts two-thirds of the way along its length. While not fully developed as transepts, they are a definite inflection to the hall and define the transition to the chancel area

25–3

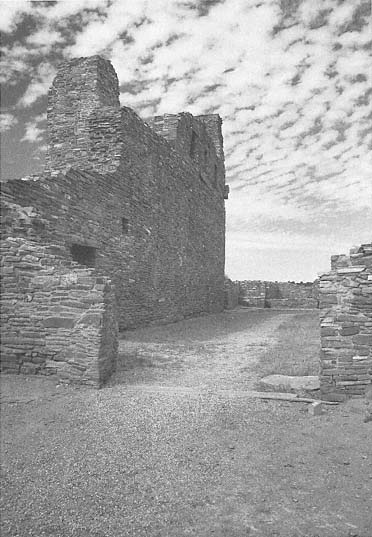

San Gregorio

The use of buttresses to stiffen the walls of the nave allowed for a

reduction in wall thickness.

[Paul Logsdon, mid-1980s]

25–4

San Gregorio, Plan with Convento

[Sources: Toulouse, The Mission of San Gregorio ; and National Park Service measured drawings]

to the north. The nave was built to commodious dimensions, roughly one hundred thirty-two feet in length and in width from about twenty-three feet at the south entrance to almost thirty-two feet at the end of the sanctuary. The nave's walls are almost parallel, which seems to refute Kubler's theory that the nonparallel relation of nave walls in New Mexican churches might have been consistently intended to make the spaces seem longer through optical illusion.[8] Any discernible impact on perception at Abo would work against this intended effect. The church was almost fifty feet in height, and with the exception of today's San Esteban at Acoma, it would have been roughly twice the height of any of the state's existing adobe churches.

On the south a narthex was formed by the extended east and west buttress of the entry facade, and to the right of the main doors a small chapel shared a terrace with the narthex. As a solution to the problem of accommodating the vast population of Abo, the campo santo might have been used in the manner of an atrio, the memory of which was fresh in the minds of the recently transplanted friars. This structure, unlike much of the construction at Abo, was made of adobe, and it is possible that this chapel was used to conduct services during the construction of the church. Until about 1640 an area below the choir loft served as the baptistry, but thereafter a new room was built to the left just inside the entrance. The sacristy, to the right or east, gave onto the sanctuary area, which was raised the typical several steps. Unlike its predecessor, the apse itself was battered inward and turned at a slight angle to the axis of the nave.

San Gregorio was constructed of sandstone, a reflection of earlier Indian building techniques. The area around Abo rests on a geological base of reddish-brown sandstone, a stone already fissured in layers and easily removed without iron technology. In driving to the church today, for example, one can see an eroded bluff cut by the nearby stream that exposes usable building material. Although the walls were to be plastered, the stone that faced the rubble core was selected and positioned to reduce irregularities in the wall surface. The stones, which were rarely larger than one foot square or more than four inches thick, were laid up dry or set in adobe mortar for stabilization. Smaller fragments could be inserted as chinks into the gaps left by stones of irregular profile. As Carleton claimed in 1853, "We saw not a single dressed stone about the ruins."[9] Although stones were not dressed, the smoothest side was usually oriented outward. The construction method was analogous to that used during the

25–5

San Gregorio

The nave and remaining portions of its west wall.

[1986]

tenth through thirteenth centuries at the various hamlets in Chaco Canyon.

Although stone is more permanent than adobe, construction time could be considerably longer. In addition to permanence, stone construction required water only for mixing the adobe mortar. Stone also permitted greater wall heights than adobe, which rarely rose above thirty feet. The walls at Abo were remarkably thin—about three to four feet—and were relatively consistent in thickness throughout the church. Buttresses provided additional strength when needed to support the clerestory beams, for example, and a number of engaged external pilasters remain clearly visible on the western side. At the corners, under the bell tower, and in the buttresses an additional mass of five or more feet in thickness stabilized the weight and thrust of the beams. With this system, which drew upon the fortified church of Spain transmitted through Mexico, the celebrants were able to build a structure of considerable dimensions using reasonable quantities of materials.

The ceiling was beamed but did not use round vigas in the more typical manner. Six squared timbers, roughly one foot by one foot in section, were bundled in groups stacked two wide and three deep. Drawing on written sources, Edgar Hewett claimed that "the beams are said to have been the most beautifully carved and most massive in the southwest."[10] On top of the vigas were the smaller savinos, in turn covered by juniper and piñon branches and then thick adobe mud. The mud-plastered roof drained to the west away from the convento. This spanning system, rather than the arches more common in Mexico, reduced the problems of thrust against the side walls and allowed a reduction in mass—hence thinner walls. Had the walls of the nave been splayed, they would also have reinforced the rigidity of the structure, although in comparison to the dead weight of the stone buttresses, this contribution would probably have been negligible. In suggested reconstructions the parapet of the nave walls is usually shown as crenellated, adding to the image of the church as a fortified structure.[11]

The increased height of the transepts, eight feet higher than the nave, allowed for the clerestory's southern orientation, which offered a continuous flow of light throughout the day. The exact height of the roof over the apse is assumed to have been equal to that of the transepts. In the chancel are the remains of three stone altars, all facing north. A choir loft spanned the southern end of the nave. The interior of the church shows remnants of the white gypsum plaster applied to the interior walls.

25–6

San Gregorio

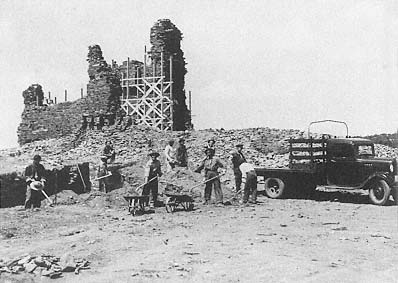

1938

Excavation and stabilization work in progress.

[Museum of New Mexico]

In some places there are also vestiges of black painted dados, which added to the sense of decoration. Doorways were cut into the walls using wooden lintels rather than arches. The floors were all packed adobe.

East of the church was an extensive convento, one of the largest in New Mexico, organized around two courtyards. Portions of the convento were constructed of adobe, and the floors in many areas were paved with sandstone flags. The "western court is surrounded by corridors into which open living quarters, kitchen storage rooms, and a room set aside for bird pens."[12] In the western courtyard a kiva was built slightly off center, possibly dating from the same time as the church. James Ivey suggested that it had been built with Franciscan approval as a transitional form.[13] It was used as a refuse pit for the convento during later Spanish occupation. The eastern courtyard was used for the friars' livestock, mainly sheep and goats, as well as for storage of goods. The entry doors to the church pivoted on iron pins, which Toulouse claimed to be the only instance of this type found in seventeenth-century New Mexico[14] —although wooden versions of the pivot were in use up to the construction of the Santuario at Chimayo in 1816. Other iron elements, which were necessarily imported from New Spain, were nails, hinges, buttons, and fire tongs, all of which appeared on the list of supposed provisions for the founding of new missions.

The admission of the Spanish into the precincts of the pueblo had the effect of a Trojan horse. Prosperity at first increased through export and trade, but material gain was more than offset by increased attacks by the Plains Indians who fed so viciously on the well-being of the pueblos. Communicable diseases, unknowingly injected into the mainstream through contact with Europeans, also contributed to the downfall of the Tompiro. And then in the late 1660s and 1670s drought and consequent famine attacked the tottering population, whose numbers dwindled quickly. As early as 1671 there were reports of emigration from Abo to the Rio Grande valley near Socorro, and by 1678 the formerly thriving pueblo was vacant and quiet. Only the wind and the Apache visited it. The former, with the infrequent rain, contributed to the erosion of the mission, while the latter probably burned down the church shortly after its abandonment. Excavations of charred timbers bore witness to this supposition.

From about 1800 to 1815 tentative efforts were made to resettle the area around Abo. Houses and utility buildings such as barns, corrals, and pens were constructed for dwelling, ranching, and farming. But these attempts were premature, and heightened Apache raids around 1830 forced the abandonment of the hamlet.

Although known, the Salinas sites were rarely visited thereafter. In December 1853 Major James Carleton, stationed at Albuquerque, took a tour of the Salinas missions and left a detailed description of how they stood at the time. He noted basic dimensions and indicated that there were no finished stones and that the woodwork had been destroyed by fire.[15] Fellow soldier Lieutenant Emory had left a picturesque but somewhat vague record of the ruins in 1848. The site became private property with the American occupation of the territory. Late in the century, with the Plains Indian threat gradually reduced, the land again provided for Hispanic habitation. This time resettlement efforts were successful, and for half a century the Cisneros family held and worked the land around the former mission.

In 1937 the University of New Mexico, already sporting a Spanish Colonial Territorial Revival campus, bought the property and held it jointly with the School of American Research. In 1938 the remainder of the site, on which the apse was located, was donated by Fred Cisneros, and the church buildings became a state monument. From June to December 1938 there were excavations and stabilizations on the site, work that continued through 1939. Late in 1981 the entire property, with Gran Quivira and Quarai, became a joint historical district known as the Salinas National Monument, administered by the National Park Service. In 1988 the name was modified to the Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument.

Quarai:

Nuestra Señora de la Purísima Concepción

(1620s?); 1630–1633; deserted by 1677

Second Church

1830 (unfinished)

One of the most distinctive characteristics of the earliest New Mexican missions is their seeming disjunction from their sites.[1] At the Salinas missions, such as Gran Quivira and Quarai, for example, huge piles of stone in areas almost devoid of communities appear like the works of some long gone or extraterrestrial peoples or gods. Charles Lummis best captured the scope of the accomplishment in his often-cited quotation about the Salinas missions: "An edifice in ruins, it is true, but so tall, so solemn, so dominant of that strange, lonely landscape, so out of place in that land of adobe box huts, as to be simply overpowering. On the Rhine, it would be superlative, in the wilderness of the Manzano it is a miracle."[2]

Of course, this effect was the builder's intention: a miracle of scale, space, mass, and light meant to impress on the native population the wonders and glory of God. And even in ruins, although now stabilized and partially restored, Quarai resolutely stands its ground against the mountains that form its backdrop.

Coronado did not come this far east before turning his attention northward toward the Great Plains. But during the winter of 1581–1582 an expedition under the leadership of Captain Francisco Sánchez Chamuscado and Fray Agustín Rodríguez reached the five villages forming the Salinas group. These pueblos comprised Tompiro-speaking Tiwa Indians, as did the communities at Abo, Tabira, and Las Humanas. All these tribes were the object of conversion attempts during the early stages of Spanish colonization.

Settlers arrived with Oñate in 1598, at which time the new province was divided into areas of conversion, each assigned to various friars. Their work did not begin immediately, however, and it was not until 1610, when more missionaries arrived in New Mexico, that their efforts commenced in earnest. Governor Oñate had toured the new territory in the late 1590s and had extorted signatures on an "Act of Obedience and Vassalage" at Acolocu pueblo, which is believed to have been situated near Quarai. As part of the Spanish economic and political campaign, the viceroy had declared that the Indians should be gathered into more compact pueblos to facilitate control and conversion and to "promote the welfare of these Indians and facilitate their administration."[3] The Indians would have been only too aware of the latter Spanish motive, and it is doubtful that they would have agreed to the former without coercion. The first conversions and the construction of the earliest church at Quarai are credited to Fray Juan Gutiérrez de la

26–1

La Purísima Concepción

View across the pueblo ruins to the second church.

[1984]

Chica, who first took up the mission at the Salinas pueblos.[4] The site he chose, or on which he was allowed to build, was a pueblo mound requiring retaining walls and fill to render it suitable for constructing a church.[5]

The best known of the Quarai missionaries is Fray Estevan de Perea, who arrived in New Mexico in 1610. He served two terms as the custodian of the Franciscans and headed the Office of the Holy Inquisition—which applied only to the Spanish—then headquartered at Quarai. The presence of this office in the pueblo led to some degree of turmoil because various conflicts between the civil and the religious authorities over the Indians and other, mostly economic matters were played out here. These problems continued during the residency of Perea's successor, Fray Gerónimo de la Llana, a native of Mexico City who came to Quarai in 1634.

Because the church of Nuestra Señora de la Purísima Concepción dates to the period 1627–1633, it is difficult to determine who was responsible for its construction. The structure was built, however, under Franciscan supervision but almost entirely by Indian labor. It is cruciform in plan, with an altar in each transept. The nave measures a full hundred by twenty-seven feet, making it one of the largest in the state. It originally was forty feet high, nearly twice the height of many of the pueblo churches still extant.[6]

The church is built of a red sandstone similar to that used at Abo. Although the walls were built with minimal amounts of adobe, the mortar contributed little to the stability of the structure, which depended primarily on the dead weight and thickness of the stonework itself. The building units were rather small, commonly one to four inches thick and usually less than one foot square. Given the scale of the unit from which the church was built, the amount of labor required to construct an edifice of this scale must have been staggering.[7]

Like Abo, the nave of the church widens slightly toward the altar, only to converge quite noticeably past the transepts. The ceiling was constructed in the usual manner over vigas taken from the nearby Manzano mountains, although the beam sockets still visible in the walls indicate a clustering of squared vigas rather than the single round ones characteristic of convento and later church construction. The building faces south and slightly west and is believed to have had two towers in its better days. A campo santo extended south from the entrance, and a walled enclosure distinguished this ground from the pueblo to the west.

26–2

Quarai

Aerial view of the church and convento ruins. The foundation outline of

the 1830 church appears on the right.

[Fred Mang, Jr., National Park Service, 1975]

26–3

La Purísima Concepción, Plan

[Source: Wilson, Quarai State Monument ]

There was a reasonably large convento at Quarai, the ruins of which abut the east side of the church. The disposition was the familiar square cloister, which included the residence of the friar, storerooms, and offices and which was adjoined by a walled corral for the animals. Much of the pueblo construction aligned with the Franciscan structures, suggesting that they were built or rebuilt after the church.

Inhabitation on the site, ascertained from pottery fragments, dates to 1300, although this earlier occupation had probably ceased by 1350. Perhaps a period of drought forced a temporary abandonment of the pueblo, as occurred in the seventeenth century. Water is found in springs southeast of the church group as well as additional sources about three miles further up the hillside—a remarkably reliable situation for the Salinas area. The pueblo at the time of the Spanish arrival contained about six hundred people, but this number later fell drastically. A description of the building from about 1641 referred to it as a "very good church, organ and choir, very good provision for public worship. 658 souls under its administration."[8] The anomalous presence of an organ demonstrated that although the agricultural yield of the pueblo was limited and meager, the profit derived from trading in textiles, animal products, and salt was considerable.

The pueblo exported salt, piñon nuts, hides, cotton mantas, and livestock.[9] In exchange, the triannual mission supply caravans brought items such as ironwork, chocolate, and "certain things used for the divine cult."[10] Trade with the Plains Indians yielded buffalo meat, hides, and captives in exchange for Pueblo corn and cotton and Spanish horses and iron knives. But peaceful trade with the Plains tribes existed side by side with violent plundering. Indeed, introduction of the Spanish horse led to increased fear in the pueblos of Apache raids. Given this new mobility, the Plains Indians discovered that raiding was more profitable than stock raising and that the risk of retribution was lessened.

By the 1670s a combination of debilitating forces was already wreaking havoc on the Salinas missions. European diseases had continually reduced the population, and when pestilence was not actually present, there was always the fear of its reappearance. Plains Indian attacks were a constant threat. In response to this latter pressure, the Quarai ostensibly attempted a peace treaty with the Apache between 1664 and 1669, but the leaders of the negotiations were found out and hanged. The Apache, no doubt less than pleased by this reversal of events, mounted attacks with renewed vigor. And drought in this last decade reduced the agricultural yield while increasing the pressure of the Plains deprecations; the Apache, too, were hungry. In 1669 Fray Juan Bernal wrote of the Apache forays, the crop failure, and the consequent starvation that prevailed throughout the pueblo. The Spanish requested more arms and troops; some of them were later reduced to eating animal hides merely to subsist. By 1678 all the Salinas missions as well as the pueblos they served had been abandoned. Quarai was most likely deserted by 1677. The Indians probably migrated first to nearby Tajique and then to Isleta, where they had linguistic kin. And then the desert and the elements took their course.

Like Abo, squared beams—here twelve inches deep by ten and a half inches wide—spanned the nave of Quarai about twenty-six feet above the floor.[11] In the transepts and apse the ceiling height was increased by an additional six feet to create the transverse clerestory that illuminated the nave. Facing nearly south, it would have provided almost constant light throughout the day.

The beams supported a field of latillas installed on the diagonal as well as layers of rough fiber matting, earth, and a finished plaster coating sloped to encourage water runoff. In the apse a lower, "false" ceiling thirty feet above the floor created a profile in which the section of the church resembled its plan; in this way the sanctuary was articulated, and its presence as the focus of the church was heightened. Similar to the roof structure, a series of thirty-five-foot-long beams ran continuously through the south wall to form a balcony without and a choir loft within.

The exterior was plastered, concealing the mason's craft and rendering the wall surfaces monolithic. Within the church the walls were covered with white plaster on which decorations "in red, black, gray, yellow, orange and probably blue, white and green" were painted.[12] Although provisions had been made in the masonry structure for the mounting of an altarpiece imported from Mexico, the wall surfaces behind the altar may have been ornamented directly to serve until the time and the means allowed for a more polished work.

Attempts to reinhabit the land around 1800 had been both premature and futile, but by 1815 clusters of houses were beginning to appear around the pueblo of Quarai and what was to become the town of Manzano. By the 1820s sufficient resources and settlers on the Manzano grant were available to establish a congregation, and on August 25, 1829, they petitioned to build their church in Manzano.[13] Within a month, however, the citizens decided that

26–4

La Purísima Concepción

The partially restored facade.

[1984]

the new church should be built at Quarai, probably because it had been the religious seat in times past.

Concepción de Quarai was still standing, with portions of its roof and convento nearly intact, well into the nineteenth century. But water damage, rot, and soil that had fallen or blown into the church had rendered the old structure unsafe and unusable. Refurbishing the old structure was not practical, and instead the Spanish settlers began to construct a small church to the southwest. They did not get very far. The instability of the Indian situation in general and an Apache attack in late 1829 or early 1830 instigated a retreat from building efforts at Quarai. The church was left barely protruding out of the ground, with its walls less than two feet in height. On July 6, 1830, the citizens again petitioned the parish priest to move the church to the Plaza de Apodaca at Manzano.

Although still noticeable a half-century later and indicated on Bandelier's sketch map of the site published in 1892, the remnants of the structure had been buried in the intervening century.[14] In 1959 the "lost" church was found by Stanley Stubbs, who mistakenly believed it to be a first church dating from 1615–1620 and similar to San Ysidro at Gran Quivira. A recent study by James E. Ivey provided a logical rationale for the 1829 date based on church patents.

The Apache raid of 1829–1830 also burned the remaining wooden structure of Concepción: openings such as the clerestory and collapsed areas of the roof served as chimneys that intensified and spread the fire. With the covering gone and weakened by the heat of fire, the walls lay prone to attacks by the elements. By the time of the early photographs, the profile of the church had weathered to softened masses, with a deep V cut dividing the towers of the facade.

The site was visited in 1853 by Major James Carleton, who gave the interim report of the church's condition:

These ruins appear to be similar to Abo, whether as to their state of antiquity, the skill in their construction, their state of preservation or the materials of which they are built. The church at Quarra [sic ] is not as long by thirty feet as that at Abo. We found one room here, probably a cloister attached to the church, which was in a good state of preservation [almost two hundred years later]. The beams that supported the roof were square and smooth and supported under each end by shorter pieces of wood, carved into regularly curved lines and scrolls. The earth upon the roof was sustained by small straight poles, well finished and laid in herringbone fashion upon the beams.[15]

26–5

Quarai, The Unfinished 1830 Church, Plan

[Source: Stubbs, "'New' Old Churches

Found at Quarai"]

26–6

La Purísima Concepción

The nave, looking toward the sanctuary.

[1984]

26–7

Quarai

The church ruins, in 1916, reveal the extent of subsequent stabilization

and restoration efforts.

[Museum of New Mexico]

The Quarai site was purchased privately in the nineteenth century and was donated to the state of New Mexico in 1913. At that time very limited excavations on the site were undertaken; not until 1934 did a joint team from the University of New Mexico, the Museum of New Mexico, and the Civilian Conservation Corps complete the excavation of the churches. Five years later efforts continued under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration, when archaeological investigations of the pueblos were also carried out. During the course of the 1939–1940 work the walls were stabilized, and new portions, from one to ten feet high in places, were added to them. (The change in the color of the stone makes these newer additions readily identifiable.) The smaller chapel southwest of the main church was discovered in 1959.

Even in ruins, the facade of the church with the remnants of two towers retains a stately presence [Plate 4]. The church was built when religious zeal, resources, and the numbers of the Indian population were all at their zenith. The memories of Mexico, not only of the fortress church but also of the stone and the scale of the naves, were the obvious standard by which the friars reviewed their intentions. When Domínguez visited the province a century later, Mexican churches were still the yardstick he used. The walls at Quarai were uniformly thick, thicker than at Abo, where buttresses were used to lighten construction.[16] Quarai was a "safer" church, more conservative in its building method. Only in the transepts, with the projected clerestory, were the walls thickened to support the increased weight. There remain two clean-cut square openings visible in the ruins, one high on the west wall and the other over the entry lighting the choir loft, the sockets for the beams of which still exist. The interior was flagged with large pieces of sandstone, roughly eighteen to twenty-four inches and as at Abo, the interior was entirely plastered. Just left of the entry is a small projecting structure believed to be the baptistry. The sacristry connects with the eastern transept, which in turn leads to the convento.

Walking through the ruins, one can easily complete the building mentally by supplying the missing roof. But a more difficult task is to imagine the quality of the clerestory light, which would have fallen on the narrow and battered chancel. Given the passage through the walled cemetery, the massive towers, the darkness at the entry, the general feeling of weight and bulk, and the compressive force of the choir loft, that light pouring on the altar must have been convincingly ethereal. As Lummis said, in the Manzano it was a miracle.

Gran Quivira [Las Humanas Pueblo]:

San Ysidro

1629–1632?

San Buenaventura

1659?–1660s

The pueblo of Las Humanas constituted the limit of culture in more than one sense. On the periphery of the Rio Grande pueblos, it was situated on the edge of a vast desert that supported only nomadic raiders. If the sky did not precisely "determine" in these lands, it certainly coerced. Water was measured by its absence, and existence was always marginal. And yet in spite of these severe environmental conditions, a community of several thousand people thrived until the Spanish arrival in New Mexico. This arrival also marked the beginning of a rapidly escalating population decline: about a century later the pueblo would be deserted.

Las Humanas, or Gran Quivira, is one of the three sites that today form the Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument. Salinas is Spanish for "salt beds", and these were the lands from which the salt so critical for the preservation and flavoring of food and for mining was extracted. From here it was shipped in trade to other parts of the province and to Mexico itself. The land, Lummis related, was not always salty. According to Indian myth, this area was once freshwater lakes, and it abounded with fish, waterfowl, bison, and antelope. But dwelling among the people was one unfaithful wife, "and for her sins the lakes were accursed to be salt forever."[1] Under the unyielding pressure of the heat of the sun, the seas evaporated, leaving the great salt flats east of the mountains.

The remains of Las Humanas pueblo are situated on a gentle rise in the rolling limestone hills that extend eastward from the base of the Chupadera Mesa. The road south from Mountainair continues through this sparsely settled landscape, and the monument is hardly discernible in the surrounding landscape. As one approaches, however, the regularity of San Buenaventura distinguishes it from the adjacent scrub and terrain. It has changed little since Adolph Bandelier wrote about it almost a century ago: "In this arid solitude the massive edifice of the church, with the mounds of the pueblo, look strangely impressive. From the west the church can be seen miles away, a clumsy parallelopiped of gray stone; from the northeast, through vistas of dark cedars and junipers, the ruins shine in pallid light, like some phantom city in the desert."[2]

Based on ceramic evidence, inhabitation on the site began some time between the seventh and eighth centuries, with A.D . 900 the latest probable date.[3] This fortuitous location formed a geographic pivot between the Jornada branch of the Mogollon culture to the south and the Rio Grande Anasazi culture to the west. Interpretation of pottery found during excavations determined that both cultures

27–1

Gran Quivira

The ruins of San Buenaventura are to the right, and San Ysidro is to the left.

[Fred Mang, Jr., National Park Service, early 1970s]

had a decided effect on the pueblo until the beginning of the fourteenth century, when the culture turned more decidedly toward the Rio Grande. The pueblo's language, like that of nearby Abo, was Tompiro. By the thirteenth century "pueblo groups of 12 or more surface buildings" had been built, with the pit dwellings of earlier eras being retained as the ceremonial kivas.[4] About seven miles west of the pueblo, wells fifteen to twenty-five feet deep provided a more reliable source of water.[5] The current average rainfall is only twelve and a half inches, most of it falling in irregular summer storms and incapable of being retained. But if water is present, the soil can be made to bear.

The group managed to thrive in spite of the severity of geographic and climatic conditions by augmenting agricultural subsistence through chasing deer, quail, bison, and rabbit and growing corn, squash, and beans—none of which required high water consumption.[6] In time geography played a decisive and in this case positive role, positioning Las Humanas as the last commercial outpost between the sedentary pueblo peoples and the nomadic Plains groups. Like Pecos, or to some degree Taos far to the north, Las Humanas became an important trading camp where the Plains Indians exchanged the products of the buffalo for the products of the soil. The pueblo's position, however, ultimately proved to be its downfall as drought and continued demands by nomadic traders for goods brought the pueblo to ruin.

Early Spanish exploration did not reach the Salinas district because the usual route turned north along the Rio Grande nearer present-day Albuquerque. Only with permanent settlement were efforts made to bring the Indians under Spanish hegemony and into the church. In October 1598 Oñate traveled through the country and found three Humano pueblos. In March 1599, Scholes reported, Oñate personally visited the provinces of Abo and Xumanas (the original spelling). Oñate wrote his superiors that he had again visited "the Xumas [sic ], where within four leagues there are three pueblos, one very large like Cia [Zia] and two smaller ones. [A]nd the two pueblos of the Salinas and the Xumanas all gave obedience to your majesty."[7]

The first friar to begin serious conversion work at the pueblo was Alonso de Benavides. Having preached a sermon in the plaza of the pueblo, he reported, "The Indians are all converted, the majority baptized, and more are being catechized and baptized every day."[8] Benavides explained that there were six churches and conventos operating in the district.

27–2

Gran Quivira

View over the pueblo toward the remains of San Buenaventura.

[Fred Mang, Jr., National Park Service, 1973]

27–3

San Ysidro

The first church seen from the exterior of its apse

[1986]

Among the pueblos of this nation there is a large one which must have three thousand souls; it is called Xumanas, because this nation often comes there to trade and barter. I came to convert it on the day of San Isidro, archbishop of Seville, in the year 1627, and I dedicated it to this saint on account of the great success that I experienced there on that day. Many were converted, and our Lord delivered me on that day, because these Indians are very cruel. Nevertheless, many leaders were converted, and with their favor, I erected the first cross in this place and we all adored it.[9]

In 1629 Father Francisco de Letrado arrived and is believed to have begun construction on the chapel of San Ysidro, which lies southwest of the main flank of the native structures. Exactly how much he completed during his tenure has not been determined, although Benavides credited him with the building of a church and convento. Archaeological evidence does not seem to bear this out, at least not to the letter, because no remains of a convento have been found in relation to the first chapel. The convento to which Benavides referred was probably a portion of the Indian pueblo that had been modified to provide a residence for the visiting priest, storage areas, and perhaps office space. Letrado left to minister to Zuñi in 1632, and for the next twenty-eight years Las Humanas remained a visita of Abo. The latter was a much larger pueblo—at least in the beginning—and was closer to the Spanish strength and farther from hostile nomad groups. A stream also provided Abo pueblo with an adequate amount of water, in contrast to the marginal and irregular sources of Las Humanas.

Ironically the first and "small" chapel of San Ysidro was among the widest of any New Mexican church, second only to the early construction of San José de Giusewa in the Jemez Mountains. Apparently even the priest supervising the building was not aware of this fact, nor did he possess the necessary knowledge of structure and construction. The span may have exceeded that allowed by the beams and the bearing capacity of the wall supporting them. The chapel, today in ruins, measured 29 feet by 109 feet, a considerable size for a first effort. Located on a falling limestone slope, part of the floor had to be built up and part excavated. Only in the eastern sections was a foundation wall laid, the remainder being built directly on the bedrock of the mesilla. Here, at the entrance (east) end, the walls were three and a half to four feet thick, while the remaining walls were kept between one and a half and two feet thick. (The stone walls at Quarai and Abo, for example, were at least three to four

27–4

San Ysidro, Plan

[Sources: Vivian, Gran Quivira ; and National Park

Service measured drawings, 1986]

27–5

Gran Quivira, Hypothetical Restorations of San Ysidro (Above) and San Buenaventura (Below)

[Lawrence Ormsby]

27–6

San Buenaventura and Convento, Plan

[Sources: Vivian, Gran Quivira ; and National Park Service measured drawings, 1983]

feet thick and could vary up to a full six feet in places. The system of buttresses at Abo allowed for the relative thinness of the walls.) At San Ysidro the minimal wall thickness courted disaster, and the width of the nave relative to its wall thickness has been offered as evidence that it was Letrado who began construction. If it had been Fray Francisco de Acevedo who supervised construction at Abo, he would have been far more knowledgeable, having had his own church as precedent, and would not have attempted the architectural daring—or ignorance—that transpired at Humanas.

San Ysidro is of the single-nave type without transepts and is oriented on an east-west axis. It was constructed of the local light blue-gray limestone, unworked, but positioned best side out [Plate 5]. The stones were set in a mud mortar, or caliche . Along the nave are two rows of what are taken to be foundation stones; Gordon Vivian interpreted these to be the bases of a row of columns that supported the roof beams.[10] Although these posts might have been intended from the start of construction, in effect forming a three-aisle church, they were probably, introduced once the bearing capacity of the walls or the strength of the beams had been tested and found wanting. The pines for the great vigas, which must have been at least thirty-three feet long, could have come only from the Gallinas Mountains at least twenty miles away and were probably positioned on seven-and-a-half-foot centers. On top of these were savinos of the local juniper, used when the span presented no problem. The usual layer of branches topped the construction, carrying the adobe mud for the roof surface. The weight of this building system was considerable and paired with the relative thinness of the walls hastened the collapse of the structure after the pueblo was abandoned in 1670. In the eastern portion of the nave the foundation stones supported columns that carried the choir loft located just inside the entry.

Not much is known about the chapel's fenestration. There were probably one or two high windows in the south wall, a common pattern, but whether there was also a clerestory is impossible to determine because the existing walls are too low for a definitive interpretation. Vivian believed that oiled sheepskin parchment covered the windows because it more easily fit into the window frames than the irregular pieces of selenite of the native tradition.[11] Throughout the centuries tales of buried wealth attached to Gran Quivira (hence its sobriquet), and treasure hunters hastened the natural processes of attrition with their forays and their digging. The floor and altar area of the San Ysidro

27–7

San Buenaventura

The nave of the church, with tapering apse and two shallow transepts

[1984]

chapel were particularly unfortunate victims of such searches.

The altar end of the church still contains the remains of the stone altar and a box believed to have held the vessels of baptism. The font itself was supported on a small stand, the fragments of which lie along the east wall near the choir loft. Remnants of a thin, sandy plaster reveal that the interior of the nave was plastered. Along the base of the wall a wainscot of dull red paint once existed, decorated above a thin black line with designs painted on the white plaster. Similar treatment may be seen today at Acoma and Laguna. Only small fragments of these decorations have been found, however, implying that at least a portion, if not all, of the nave was so decorated.

West of the church's simple planar facade lies the burial ground, which is surrounded by a low stone wall and is focused on a single cross set on a stone base. Like the later San Buenaventura, the stone wall of the church might have been integrated into the circumferential wall of defense around the pueblo.[12]

San Ysidro represents a common second stage in mission development: the extension of development efforts from the existing spaces of the pueblo (first stage) to a small, temporary church for use until a larger structure was warranted. Single-nave buildings of the same type as San Ysidro include one at Tabira (1629), the earliest chapel of San Miguel in Santa Fe, and the "lost" Pecos church from the first two decades of the 1600s.[13] The church of San Buenaventura illustrates the third phase of mission establishments in the New Mexican religious campaigns: substantial edifices meant to endure.

Given the location of Las Humanas in the marginal areas of Pueblo culture, it is difficult to explain why a church this large could have proven insufficient. Rather than increased needs, the deterioration of the existing chapel or the desire for a less marginal position could have instigated the construction of a more ambitious edifice to the west of the old San Ysidro. The population already had seriously declined by the 1660s, perhaps by as much as fifty percent, from the 1627 count of 2,000 people.

During the 1650s the Apache raided the pueblo, destroyed the church, and carried off seventeen women and children as captives.[14] In 1659 Fray Diego de Santander arrived at Las Humanas, found the existing chapel in poor repair—perhaps in ruins—and began construction of the church and convento of San Buenaventura. These structures were still incomplete at the time of his departure three years later, although he is usually assigned credit for their erection.[15]

Gran Quivira witnessed one of the most exaggerated conflicts between the civil and the religious powers in New Mexico's history. Until Santander began his residency, Las Humanas had been administered from Abo. Nicolás de Aguilar, the alcalde mayor , came to the pueblo in the 1660s as a loyal executor of Governor Bernardo López de Mendizábal. Mendizábal had no love for the church, a fact borne out by his continuing program of personal gain at the expense of the religious venture. As Santander was trying to reestablish the position of the church in the pueblo, Mendizábal was waging a campaign against the religious by forbidding the Indians to work on the church's construction. The governor, Charles Hackett noted, "commanded under penalty of death that no Indian work on the structure; but the Indians continued at great risk in the construction of the edifice, for they had no church."[16]

This proscription was fueled by the traditional enmity between the missionaries and the governor's office. Indians working on construction could not be tending flocks, weaving, or growing corn. And if crops and other goods were produced for the religious, the friars were accumulating wealth directly in competition with the governor. The father replied to the governor that a church was needed to bring the word of God to the Indians. Unconvinced about such expenditures of time and resources, the governor replied "that churches with costly ornaments and decoration were not necessary; that a few huts of straw and some cloth ornaments, with spoken masses, were ample."[17] Construction continued, no doubt under the disgusted eye of Aguilar, who kept the governor informed of the pueblo's affairs.

Although the width of San Buenaventura is less than that of its predecessor, almost every other aspect surpassed the earlier structure. The nave is about 27 feet wide, with a length of 109 feet. There are two transepts barely 6 feet in average depth that hardly alter the impression of a single-naved church. The transepts are more symbolic than perceptual, although even these slight extensions allow for use as side altars. Like San Ysidro, the church is aligned on an east-west axis, with entrance again to the east. The original campo santo must have served for burials, as none fronts the second church.[18]

The construction technique remained the same: walls of local limestone laid in mud mortar but this time worked to a wall thickness of five feet or more.

27–8

San Buenaventura

The convento, its first courtyard seen in the center (walls with window openings) [1986]

The facade was planar and showed no traces of towers, although the remaining stone walls seen today offer that impression. A central door led directly into the nave through a tapered entrance spanned by a composite wooden lintel. The baptistry lay just to the right of the entry.

Evidence indicates that the building was never finished, although portions of its wooden structure had been installed, including the choir loft at the east end of the nave. This "entablature," as Major Carleton referred to it in 1853, received considerable carving and detail, but the church was never roofed.

Ornamentation, the last stage in the construction of a church, indicates that the edifice was nearly completed, although the corbels and beams were carved prior to installation. Because the span was shorter than San Ysidro's, vigas spared from the Apache desecrations could have been used in roofing the new church. Carleton was clearly impressed by the quality and the amount of carved ornamentation:

Some of the beams which sustained it [the choir loft], and the remains of the two pillars that stood along under the end of it which was nearest to the altar are still here; the beams in a tolerable good state of preservation—the pillars very much decayed; they are of pine wood, and are very elaborately carved. There is also what perhaps might be termed an entablature supporting each side of the gallery, and deeply embedded in the main wall of the church; this is twenty-four feet long, by, say eighteen inches or two feet in width; it is carved very beautifully indeed, and exhibits not only the greatest skill in the use of various kinds of tools, but exquisite taste on the part of the workmen in the construction of the figures.[19]

The illumination of the church presents other problems of interpretation. Vivian, after Kubler, assumed that there was the typical window illuminating the choir loft from the east as well as one or more windows high on the south side of the nave.[20] The existence of a clerestory cannot be definitely determined by archaeological evidence, although transept-type churches from this time usually possessed a transverse clerestory.

Along with the church, Gran Quivira now boasted a developed support structure. The extensive convento south of the church included a full sacristy with access from the south transept and a complete quadrangle of living and utility spaces. Lying further south was a large corral measuring sixty by fifty-three feet and an adjoining stable area. As the pueblo declined, the mission flocks and herds were moved to Abo, where food and water were more plentiful and the Apache slightly less in evidence.

By the middle of the 1660s conditions had turned even worse. As early as 1663 Alcalde Nicolás de Aguilar had sympathetically reported that "it costs a great deal to get water and it makes a lot of work for the Indians in obtaining it, and the wells are exhausted and there is an insufficient water supply for the people, for their lack of water is so great that they are accustomed to save their urine to water the land and to build walls."[21] The population fell to about one thousand. During the end of the decade no crops were harvested, and starvation became another of the population's miseries: at Las Humanas at least four hundred fifty people died. Those who did not die were seriously weakened and more prone to contract or expire from disease. Fray Juan Bernal, writing in 1669, described the horrible scene of the great number of Indians "lying dead along the roads, in the ravines, and in their huts."[22]

Conditions were no better for the Apache. What had been denied them through trading, they now attempted to extort through attack and theft. But there was little left to steal, except perhaps human life, which could be sold into slavery in exchange for life's necessities. The Apache displayed their rage by destroying the church on September 3, 1670. The situation had become intolerable. In either 1671 or 1672 the pueblo was finally abandoned to the desert, the Apache, and, in time, the Anglos.[23]

The site had sporadic visitors over the centuries. At the time of Major Carleton's visit in 1853, the ruins of the churches were still visible. The pueblo itself had been transformed into a series of earth-covered mounds, only parts of which have yet been excavated. Tales of buried treasure still brought many seekers, and even after the transformation of the site into a national monument in this century, permits were granted for digging. No treasure was ever found.

More scientifically, the School of American Research and the Museum of New Mexico undertook excavations of San Buenaventura commencing in July 1923 under the direction of Edgar L. Hewett. In 1951 National Park Service archaeologist R. Gordon Vivian undertook excavations at Gran Quivira that provided a more complete picture of the chapel of San Ysidro as well as parts of the pueblo proper. Gran Quivira National Monument was established on November 1, 1909; in the fall of 1988 it was incorporated with Abo and Quarai as Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument.