Albuquerque:

San Felipe Neri

c. 1706; 1793; 1880s

Albuquerque today displays precious few signs of its original Spanish colonial founding. The city is mostly modern and predominantly postwar modern, as is typical of many Sunbelt cities. Only weak stylistic references or slight vestiges of an adobe tradition or the basically earthen brown color palette of its architecture gives a hint of the villa founded on the banks of the Rio Grande some two and a half centuries ago. Central to that founding was the parish church of San Felipe Neri, although that was not the name of the church when it was first consecrated.

Albuquerque was the third villa to be established in New Mexico, if the first tentative capital of San Gabriel is discounted. Albuquerque's founding directly responded to the domestic needs of the evergrowing number of Spanish settlers trickling into the province after the Reconquest. In the north sixty-six families crowded into the limited confines and agricultural lands in and around Santa Fe, and to meet the problem, Governor Vargas ordered the settlement of "La Villa de Santa Cruz de los Españoles Mejicanos del Rey Nuestro Señor Carols Segundo" on April 12, 1695. The valley's Indian inhabitants were ordered displaced, and some of the families moved north after the order. (See Santa Cruz.) The founding of the new town helped ease pressure on the capital, yet settlers continued to arrive in the province. Albuquerque, on the other hand, was established to serve settlers already living in the area.

Communication between New Mexico and the mother country was slow, and the authority for gubernatorial appointment rested with the king of Spain on advice from the Council of the Indies. Upon Vargas's death in 1704, as an interim measure the viceroy, duke of Alburquerque, appointed Francisco Cuervo y Valdés as the acting governor. In the principal gesture for which he is remembered, Cuervo y Valdés resettled thirty to thirty-five families on a piece of land along the Rio Grande between Sandia and Isleta pueblos and named it "La Villa Real de San Francisco de Alburquerque"—the last reference was undoubtedly intended to garner some favor from his overlord. The year was 1706. Unfortunately, the acting governor was overstepping the boundaries of his duty in establishing a town since settlements were supposed to be approved by the viceroy and ultimately by the king. Instead of a reward from the viceroy, Cuervo y Valdés received a reprimand. At the same time the patron saint of the nascent villa was changed from San Francisco to San Felipe Neri; the simpler spelling eliminating one r —Albuquerque—came with time.

23–1

San Felipe Neri

The elaborated tower finials crown

the Neo-Gothicized church.

[1981]

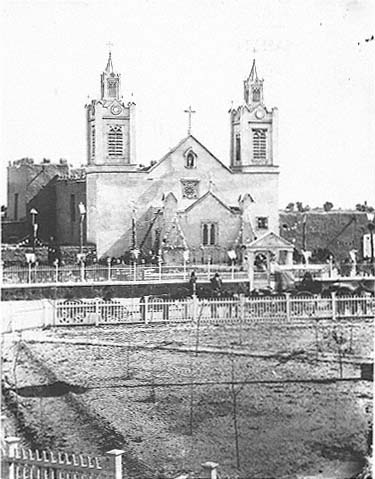

23–2

San Felipe Neri

1881

With its elaborate turrets and white picket fence, the church appeared

quite Anglo and "proper" in 1881. A look beyond the facade, however,

would have revealed the church's Hispanic origins.

[Ben Wittick, Museum of New Mexico, School of American Research

Collections]

A church was soon constructed, although not on the site where it resides today. The plan of the city was based on the royal ordinances of 1573, which declared that each town should be centered on a plaza mayor, with streets extending from it on the pattern of the gridiron. But New Mexican towns rarely followed the letter of the law. The church itself served a congregation of settlers numbering roughly two hundred thirty-two and included some limited elements of a convento for the priest's use.[1] In his 1760 report on the town, Bishop Tamarón remarked, "This villa is composed of Spanish and Europeanized mixtures. Their parish priest and missionary is a Franciscan friar. . . . There are 270 families and 1,814 persons."[2] There was an adjustment in the number of duties expected of the priest in consideration of the distance between settlements and the difficulties in getting to Santa Fe: "And the title of vicar and ecclesiastical judge of this villa was issued to him [the priest] because of the distance."[3] Tamarón, however, gave no description of the church itself, although he did recount a somewhat amusing incident about the problems caused by the scattering of the ranchos necessary to secure fertile and irrigatable lands:

Because some of his parishioners are on the other side of the river, this parish priest of Albuquerque, called Fray Manuel Rojo, is obliged to cross it when summoned. This kept him under apprehension, and above all he emphasized to me that when the river froze, it was necessary to cross on the ice. He elaborated this point by saying that when the ice thundered, he thought he was on the way to the bottom, because when one crosses it, it creaks as if it were about to break.[4]

Visiting the villa real some sixteen years later, Domínguez provided a complete description of the church structure, noting that it was "adobe with very thick walls, single-naved, with the outlook and main door to the east."[5] The convento faced south. As Bainbridge Bunting pointed out, the present church shares neither this orientation nor these dimensions, indicating that a new church rising on the site in the 1790s modified its orientation.[6]

About the villa of Albuquerque, Domínguez was more positive:

The villa itself consists of 24 houses near the mission. The rest of what is called Albuquerque extends upstream to the north, and all of it is a settlement of ranches on the meadows of said river for the distance of a league from the church to the last one upstream. Some of their lands are good, some better, some mediocre. They are watered by the said river through very wide, deep irrigation ditches, so much so that there are little beam bridges to cross them. The

23–3

San Felipe Neri, Plan

[Sources: Plan by Arthur H. Lewis, Architects; and

measurements by Dorothée Imbert and Marc Treib,

1987]

crops taken from them at harvest time are many, good and everything sown in them bears fruit.[7]

Its church facade was plain, a two-panel door "with a good lock" for an entry and two windows facing south. The clerestory illuminated the nave, while one window above the entrance lit the choir.[8] On each side of the nave were two altars, with "poor" or "badly made" furniture.[9] The condition of the interior was not good, and Domínguez noted that all the furnishings were worn. "The floor of this church is the bare earth," he added, "and its aspect is gloomy."[10] The square convento fared little better; it was basic and minimal, with "no cloister, but just a bare patio."[11]

Following the typical New Mexican pattern, the town dispersed, rather than concentrated, as it developed, and as a result the distance between parishioners increased. The church's substance decayed. By 1793 a new church or extensive repairs had been undertaken, mostly with the aid of Indians from Tome and Valencia. Bunting and Kessell have dated the present church to this 1793 rebuilding.[12]

For the next century the traditional forms were retained and maintained in decent repair, although with the usual lapses of attention. While descriptions are not exact, the church's present-day twin towers are found in a wood engraving from the 1850s.[13]

Two results of the 1846 American takeover of New Mexico had a direct impact on the form of San Felipe Neri. The first was the transference of the bishopric to Santa Fe, a move that severed ecclesiastical ties with Mexico and created a need for a cathedral worthy of the name. The second was the arrival of the railroad in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. New Mexico's first bishop, Jean-Baptiste Lamy, displayed little sympathy for the rudimentary expression of Hispanic churches and the passion of their art. In place of the traditional adobe masses came the transplanting of European medieval Gothicism, although its architectural vocabulary was quite varied and indistinct by the time it reached New Mexico. Gothic touches thus came to overlay the earthen Hispanic forms in hopes of conveying a more polished image and, one assumes, pride to building and congregation. The railroad, which provided milled lumber, metal for roofs, Eastern styles, and stock ornamentation, was the vehicle by which this architectural refurbishing program was implemented.

Under the direction of Father Joseph P. Macheboeuf, who had accompanied Lamy and thereafter served as parish priest, the look of the church began to change.[14] In 1868 Italian Jesuits assumed the ad-

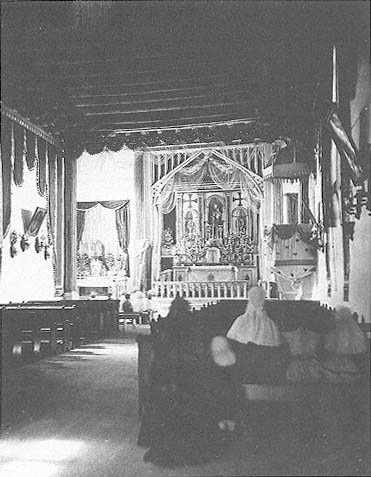

23–4

San Felipe Neri

1881

The interior of the church before the pressed metal ceiling and arches

were added.

[Ben Wittick, Museum of New Mexico, School of American Research

Collections]

ministration of the church and furthered the renovation efforts. A porch was added to the entrance, and the gothicization commenced. An 1881 photograph shows an almost complete transformation. The towers have been stepped, effecting a neat transition from the massive adobe base to the finicky detailing of the two-staged towers. Louvers over the belfry, like those at San Miguel in Santa Fe or the old Isleta church, continue the new architectural program. On the projecting porch there are two small end towers that recall the twin towers of the Santuario of Chimayo and no doubt express the same call to a somewhat lesser degree.

In all, the transformation of the exterior of the church was conclusive. The Gothic version of this adobe mission, with its mouldings, its touches of crenellation, and its pointed, arched, louvered windows, sat comfortably and harmoniously with the picket-fenced plaza it faced, a remade American plaza complete with requisite Victorian bandstand. The Hispanic elements remained, yet each had been overlaid with a hybrid of French, Gothic, and Anglo styles. Ecclesiastical Albuquerque tried passionately to join the United States, architecturally if not temperamentally.

From his journal entry of November 3, 1881, we learn that Bourke was impressed by the remodeling: "The cathedral of Albuquerque is a modern building of good size, double towers in front and of neat and attractive, but not imposing appearance. The interior is kept neat as a pin. It is the only Catholic Church in the Terry [sic ] provided with pews,—each of these marked plainly with the name of owner or occupier."[15] The same was not the case for the interior of the building, whose traditional aspects belied its origin as a Hispanic New Mexican parish church. The Victorian garb was just that, a reclothing to bring a classic form up to date. Inharmonious in some respects, clumsy in others, the decor lucidly illustrated the state of the territorial architecture idea in the late nineteenth century [Plate 18].

The transverse clerestory was lost with the installation of the metal roof, an addition that canceled the dramatic quality of light on the altar. A wooden floor covered the packed earth that had been the only floor surface for over a century and a half. Perhaps most curious and most ingenious was the manner by which the ceiling disguised the structural vigas and corbels of the eighteenth-century church. In sheathing them with nonstructural, stamped metal ceiling panels, the builders established vague references to both the vault and the then-current construction of the cathedral in Santa Fe, which

23–5

San Felipe Neri

The walls have been painted to resemble stone; columns and nonstructural

arches overlay the adobe walls.

[New Mexico Tourism and Travel Division, no date]

23–6

San Felipe Neri

Detail of the Victorian pressed metal and painted

ornamentation in the sanctuary of the church.

[1986]

provided inspiration for some of the detailing. The arches that sprang from the tops of the pilasters seemed inconsistent, yet harmonious, and the net effect of the package successfully countermanded the usual horizontal progression of the nave. The increased availability of glass from rail shipment permitted larger windows—like those at Ranchos de Taos, for example. If the quality of light was lost by blocking the clerestory, at least the volume of light could be equaled, if not actually surpassed. In commenting on the amount and quality of detailing, Bunting wrote, "The lavish use of sawed boards, and elaborately cut designs for crosses and crockets, finials and tracery show the relish with which the local carpenter availed himself of sharp metal tools and the unlimited supply of finished lumber."[16]

Much of the detailing created its own style and suggested that the builders worked from an interpretation of how "someone had heard things were supposed to be," working perhaps from printed images or verbal descriptions. The plaster walls were painted to look like stone, and the religious icons, as Bunting noted wryly, originated far from the territory: "If the invoice for these statues could be found, it would almost certainly indicate St. Louis as the source of supply, although the ultimate point of origin was undoubtedly some forgotten European plaster works."[17]

The church still retains a choir loft with an intricate railing of milled lumber. A spiral stairway in one of the towers provided access to the choir loft; a more recent stairway was added during the late 1880s–1890s.[18]

San Felipe Neri, like many churches, has had its share of controversy. In the mid-1960s there were plans to expand the church to accommodate a larger congregation and bring its form into accord with the Vatican II decision allowing celebrants more immediate contact and involvement with the mass. These plans, prepared by a Santa Fe architect, would have destroyed not only the feeling of the Victorian version of an adobe but also any feeling of what had been there historically. Restoration, remodeling, and enlargement are all complex processes with no perfect solutions. But in the case of San Felipe Neri, the "real" Victorian forms—which are today being created in an ersatz manner from coast to coast—would have lost out to a characterless 1960s version of Hispanic colonial. If some critics deride the Victorian drapings as dating from an era and a people out of accord with the Hispanic origin of the church's history, what would a future critic think of the complete destruction of both the colonial and the Victorian?

The 1960s remodeling of San Agustín at Isleta—that is, the removal of its turn-of-the-century Gothic appliqué to a restored version of a mission style that never really existed—left San Felipe Neri as the only major New Mexican church illustration of the manifest changes in style that accompanied the American takeover [Plate 19]. Under the gloss of decoration that reveals the church fathers', the parishioners', or the city's aspirations in the late nineteenth century, colonial intention remains discernible, even if the church does not completely reflect eighteenth-century Hispanic building style. The building's mass and cruciform plan; the presence of the choir loft; the positioning, if not the idiom, of the altarpieces; and the twin towers that still bracket the entry all serve as reminders that the foundation of the church and the community is Hispanic. As the proposed remodeling was never executed and close to twenty years have elapsed, perhaps the threat is over; one can only sigh with relief and hope the project will never come to pass.

More recently another problem has arisen. Old Town Albuquerque has become one of those places that seem to have sprouted up like weeds across the United States. Seeking an economic viability for the preservation of historic districts, many of which require extensive maintenance and considerable capital, communities find that the only viable solutions lie in the creation of tourist districts. "Real" functions—necessary services and neighborhood shops—moved out, and their places were filled by tourist-oriented souvenir shops, restaurants, T-shirt stores, and the like. There were also problems with drinking in the vicinity of the church. Church authorities asked the city government on several occasions to restrict the sale of alcoholic beverages within a certain radius of the church's doors. The city did not comply, and in response authorities closed the church at all times other than at mass and devotional services.[19] One can only hope that this problem will be remedied in the not too distant future so that San Felipe Neri, possibly the one authentic element in the quasi-Disneyland atmosphere of Old Town, can be open freely to the public for inspiration, education, and even enjoyment.