Jemez Springs:

San José de Giusewa

(c. 1600); 1621–1622; 1625–28; abandoned c. 1630

The mere bulk of San José de Giusewa set in the hillside, its height, and its commanding proportions evoke the very image of stability, and its presence high on the canyon hillside seems inevitable. Yet missionary efforts on the site lasted hardly two decades, leaving only the piled stonework as a testament to the ambition and hope of its founders.

When an offshoot of the Coronado expedition under the direction of Francisco de Barrio-Nuero ascended the Jemez Mountains in 1541, it came on a community settled in several diverse units. At that time there may have been as many as eleven distinct villages occupying sites along the Jemez River and the canyons to the east roughly centered around what is today called the Jemez Hot Springs. Casteñeda gave the number of pueblos as ten; Espejo, seven; and Oñate, nine.[1] Giusewa means "place of boiling waters" in Towa, a reference to the hot springs found nearby. According to Paul Walter, by 1709 the Jemez Indians had abandoned the Giusewa site and had built their present pueblo further down the canyon.[2] Religious work in the Jemez district was assigned to Fray Alonso de Lugo, who concentrated his efforts in the canyon where the ruins of the church of San José now rest.

Spanish missionary policy required the sedentary residence of the Indians, a policy that in turn demanded the consolidation of scattered villages. In New Mexico this policy was usually unnecessary because the Indians were already resident in sufficiently dense pueblos linked to fields under cultivation. In the Jemez district, however, the missionaries were few (only one in the beginning), and the distances to be traveled between the various pueblos were too great to maintain either rigorous religious or military control. With continued efforts at concentrating settlement, the Spanish were relatively successful in consolidating the indigenous peoples into three pueblos: Astialakwa, Patoqua, and Gyusiwa (Giusewa).[3] Of these, the third was the largest and was thus the center of religious life. Scholes believed that Fray Alonso resided at one of the pueblos, probably Giusewa, and must have erected at least a rudimentary chapel some time around 1600.[4] From 1601 to 1610 the mission probably suffered intermittent abandonment, and Christianization attempts ultimately failed.

Fray Jerónimo de Zárate Salmerón was appointed custos of the New Mexican missions and was assigned to Jemez in 1617, although Scholes dated his arrival no earlier than 1621.[5] Undaunted by the apparent lack of success of his predecessors, Zárate Salmerón claimed that he executed no fewer than 6,566 baptisms in his time there. He no doubt im-

22–1

San José de Giusewa

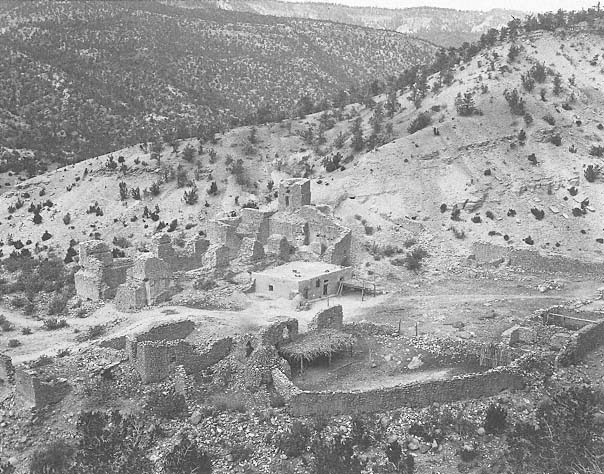

1880

The ruins of the church seen from across the valley.

[John K. Hillers, Museum of New Mexico]

22–2

San José de Giusewa, Plan

[Source: Kubler, The Religious Architecture ]

22–3

San José de Giusewa

The thickened base of the facade strengthens the sense of entry and

permanence.

[1981]

proved the condition of the Lugo structure or perhaps began a new church of his own in 1621–1622, with construction completed in 1625–1628.

Zárate Salmerón founded a second congregation called San Diego de la Congregación, another mission, in 1622. One year later the church and its convento were in ruins and the congregation scattered. In spite of his considerable faith, he left the district shortly thereafter because of the unsettled conditions.

The Jemez and the Navajo were traditional enemies, and the presence of the Spanish among the former did little to quell their basic mutual animosity. Fray Martín de Arvide assumed charge of the venture at Jemez in 1628 and reassembled those Indians who had abandoned their reductions. Little is known of his contributions toward mission construction, although Kubler stressed that a church had been built prior to Arvide's arrival.[6] When Benavides visited the area about 1629, he noted that the Jemez people had been "almost depopulated by famine and wars," but he described the church itself (credited to Zárate Salmerón) as sumptuous and beautiful and the convento as interesting.[7] Notwithstanding Benavides's positive and somewhat optimistic description, the institution failed once again and was abandoned sometime shortly after 1630.

There are few references to San José from this period to the 1680 revolt, which has led historians to believe that from 1630 on the newer San Diego became the active congregation and that, as Scholes contended, San José was abandoned sometime between 1632 and 1639. A 1664 copy of a report from 1642 remarked that "the pueblo of Jemez has a splendid church, a good convento, a choir organ, and 1,860 souls under its administration," but this description referred to the new church of San Diego.[8]

The church of San Diego endured. Founded in 1622, it was burned in 1623 and was rebuilt by Martín de Arvide in 1626 or 1628. Fray Juan de Jesús María was fatally shot in the shoulder with an arrow while at the altar and was buried there, but he was later disinterred by Vargas after the Reconquest. "The difficulties with regard to confessions and catechism continue," recorded Tamarón in 1760, but he said nothing of the church itself.[9] Kubler noted a new church built at Jemez in 1856; Bourke recorded "that it had collapsed about ten days ago" in 1881.[10] Presently located in the pueblo of Jemez some few miles downriver, a structure was built in 1919 in a style hardly of the Hispanic tradition.

22–4

San José de Giusewa

The floor of the nave was cut into the hillside, with the rubble removed in the process deposited at its lower end.

[1981]

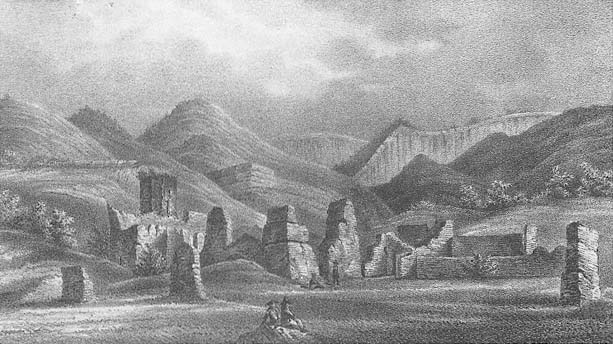

22–5

San José de Giusewa

1852

In this mid-nineteenth-century lithograph San José is treated romantically, the ruins and hillsides cut from the same

material.

[From: James Simpson, Journal , Museum of New Mexico]

22–6

San José de Giusewa

In spite of the cut-and-fill system used to flatten the slope, the altar

(chancel) end of the church was elevated more than the usual few steps.

[1981]

The church of San José de Giusewa, even in its fragmented state, provides an excellent picture of the sanctuary at the time of its construction in the early seventeenth century. By New Mexican standards it is an extremely large edifice, measuring some one hundred eleven feet in length and almost thirty-four feet in width. Its somewhat hybrid plan consists of a single nave with a stubby western transept that possibly served as a subsidiary chapel. The canyon is relatively narrow at the church's site (the intersection of a stream and the Jemez River) and provided little available flat land for construction. As a result, part of the nave was dug into the adjacent hillside, while other areas had to be filled. The floor of the church was built in two levels with a space in between filled with ashes and charred wood. This technique was used to absorb any water seeping in through the walls or the floor because excavation into the hillside interrupted the drainage pattern of underground waters moving toward the stream.

The church was built of local sandstone set in an adobe mortar, and its walls were massive: up to six feet thick in places on the west and eight feet on the east. The walls extended five to six feet above the roof level, which suggests that originally a crenellated parapet could have been used for combat from the roof. At the rear of the church an octagonal tower, sometimes interpreted as a chapel, extended about forty-eight feet above the church, with a doorway that gave directly onto the roof. Obviously this church was constructed with an eye as much to the Navajo as to God, continuing a tradition of fortress churches found in Mexico and Old Spain. The roof construction was supported by vigas, and traces have been found of the matting placed above the smaller roof pieces, in turn covered with pine needles and earth to form the final roof surface.

The nave is oriented north-south, directing the principal facade and entry to the south. The hillside is slightly less steep on this side of the canyon, and the exposure to the sun is considerably better, a particularly important feature during the winter months when the surrounding hill cuts off the sunlight early in the day. The presence of the tower and the access to the roof suggest that there was no clerestory, although the evidence is not conclusive. Remaining fragments indicate the presence of a balcony along the front of the church, perhaps also graced by two towers capping the wall, although these were not expressed as buttresses in plan.

The nave is lined with twelve low platforms, twelve by eighteen inches, which are believed to have once served as pedestals for sculpture or lighting units. The floor is stepped quite drastically in the chancel area, indicating that there have been efforts to minimize excavation. A door in the east connects the nave with the convento. As already noted, flat land on the site was severely limited, and as a result the convento, which included a small chapel, living rooms, kitchen, and sleeping rooms, took a relatively irregular disposition. To the south of the church and forming its forecourt is the burial ground, which once extended almost to the stream.

Although the church was built of stone, its interior was finished with gypsum plaster. Traces of coloring were found during excavation, which indicated that murals had been painted on the base white coat on the interior of the church. These murals were executed al fresco, that is, painted when the plaster was still wet, a technique quite rare in New Mexico. The windows of the church, quite high in the walls, were made of selenite, a micalike rock easily fractured to produce thin translucent panels. A good quantity of fragments of this material was revealed in excavation.

In 1921 two claimants to the property donated the ruins to the School of American Research. In that and the following year a team of archaeologists under the direction of Lansing Bloom excavated the site. From 1935 through 1937 work was continued at Giusewa by the Civilian Conservation Corps. More recent excavation work was performed by the Museum of New Mexico in 1965.

Archaeological investigation of the church has been extensive. Yet only a fraction of the pueblo has been excavated, although it is believed to predate the church by almost three centuries. The site is today owned by the state and administered by the Museum of New Mexico.