San Felipe Pueblo:

San Felipe

1605; 1706 (new site); c. 1801

The earthen architecture of a pueblo looks so resolute and wedded to the site that it is difficult to believe that at some time in the past those buildings might not have been there. The structures read as geometric landforms, while the plaza spaces and alleys recall a slightly more confined and formalized version of the canyons that surround the site. Seen from the elevated bank across the river, San Felipe elicits just this feeling: as if it had always been in just this place, in more or less the same form.

But this is not the case. The pueblo has actually been moved at least twice since the time of the Spanish entrance into the province. In 1540 Coronado passed through this land on his move north and found the pueblo at the foot of Tamita Mesa. Some fifty-one years later Castaño de Sosa stopped at the village and christened it San Felipe, overlying its native Keres name of Katishtya. Apparently there is no translation for the name; Hesse, for one, said he had never been able to discover one.[1]

On Oñate's entry into the territory, the various religious personnel were assigned their posts and duties. Fray Cristóbal de Quiñones was assigned to San Felipe, and it was he who supervised the construction of the pueblo's first church, built in 1605. He died two to four years later and was buried inside the mission.[2]

Benavides described San Felipe only as part of his generalized description of the Keres, saying that it probably contained a joint population of "more than four thousand souls, all baptized" and that it possessed three "very spacious and attractive churches and conventos."[3] Some few decades later San Felipe was specifically credited with "350 souls, a good church and the provision for public worship is very well arranged."[4] Like nearby Santo Domingo, it boasted a choir, an organ, and other musical instruments.

After the Pueblo Revolt and the Spanish retreat to El Paso, the San Felipe church fell victim to the whim and revenge of the natives and the elements. When Vargas reentered the province, he found the pueblo relocated on the top of the adjacent mesa, no doubt for protection against both the predictable return of the Spanish and the other hostile Indian groups. Thereafter, a church was built on this elevated site, a small church of stone measuring twenty by fifty-four feet set in the northeast corner of the plaza. Although down to its foundations, and immediately adjacent to the eroded edge of the mesa, the ruins of the church are still visible in a 1967 aerial photograph.

Either Vargas was successful in goading the inhabitants into coming down from their mesa top to

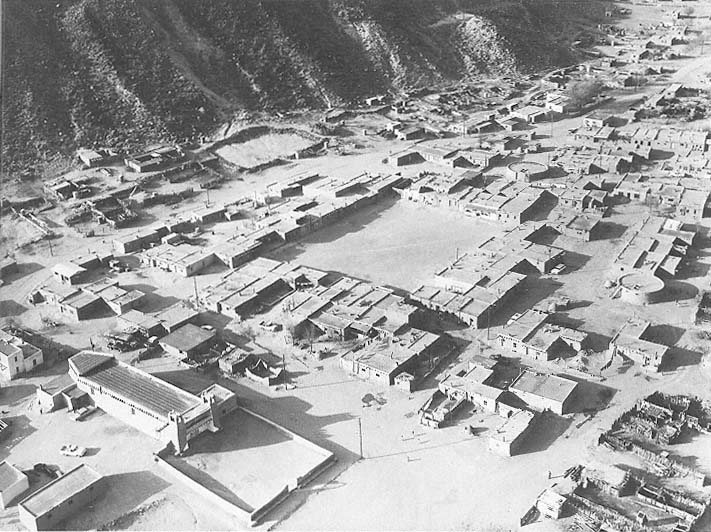

20–1

San Felipe

San Felipe has one of the best-defined plazas of all the pueblos. The church, at the lower left, is long and low, its

walled campo santo enclosing a square courtyard.

[Dick Kent, 1960s]

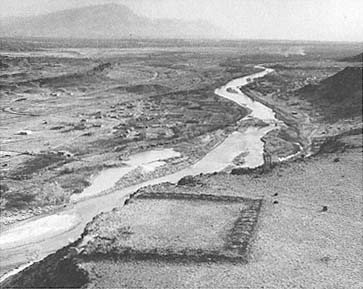

20–2

San Felipe

The ruins of the early church on the mesa are still visible in this aerial

photograph.

[Dick Kent, 1960s]

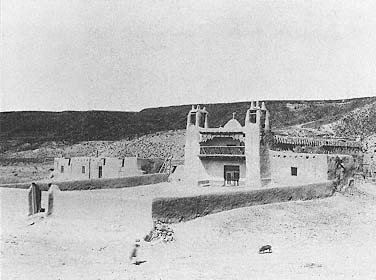

20–3

San Felipe

1899

A classic example of the two-tower facade type, San Felipe has aged

gracefully in this turn-of-the-century view.

[Adam C. Vroman, Museum of New Mexico]

the more manageable lands along the river, or they realized that the probability of attack by other natives had been greatly reduced with the return of the Spanish. In either case there was no longer any need for living in this defensive and inconvenient position distant from water and fields. And so San Felipe pueblo was moved to its present location, somewhat reversing the migration pattern of the Anasazi at Mesa Verde, as they shifted downward from the mesa into the caves.

The pueblo today is formed around a single, highly defined square and slightly concave plaza that orients to the river to the east. Some time shortly after 1700, probably near 1706, a church was built at the new site south of the pueblo, and here it remains.

Fray Juan Álvarez reported in January 1706 that both the pueblo's residential structures and kivas and the new church "are being built, the latter having been moved down from a high mesa."[5] This early structure proved insufficient for the needs of the community, and a larger church was constructed in 1736 through the efforts of Fray Andrés Zeballos. Little attention, however, was paid to the convento in which he lived, adding, in retrospect, greater commitment to his vows of poverty. In 1743 a Franciscan successor, Fray Pedro Montaño, set to remedy the priest's living conditions, which he found deplorable. Montaño prided himself on the results:

All this [fixing the convento, stables, corrals, all of which were in ruinous condition] I repaired and put in order, raising the walls anew, cleaning out and leveling everything that was uneven and full of sand for the most part, all at a cost of great diligence and care, and labor in order to incline the Indians. I stayed with them in person like a shadow, not even giving them the time to go and eat, so that they might not get away and quit their labor.[6]

Kubler specified that roof repairs directed by Andrés Zeballos were undertaken in 1736 and involved "the use of 84 canales or drain spouts, probably signifying a church of some size."[7]

Tamarón passed by in 1760 but offered no description of San Felipe; he seemed intent on getting on to Santo Domingo. Domínguez, however, with his usual thoroughness, left a complete description of the church, convento, and pueblo:

The church is adobe with thick walls, single-naved, with the outlook and main door to the east. . . . The sanctuary is marked off by four steps made of wrought beams. . . . It is as wide as the nave and as much higher as the clerestory demands. The choir loft is in the usual place and like those of the mis-

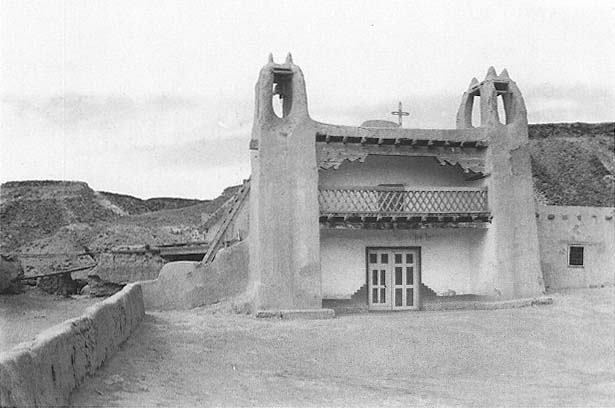

20–4

San Felipe

circa 1935

Exposed to erosion in four sides, the pillars of the towers appear badly worn. Note also the geometric painted

ornament around the doors and the carved and overscaled corbels supporting the roof of the balcony.

[T. Harmon Parkhurst, Museum of New Mexico]

20–5

San Felipe

1919

The attenuated length of the nave about which Domínguez commented late in the eighteenth century is apparent

when viewed from the flank.

[Museum of New Mexico]

sions that have them. Its entrance is from the flat roof of the convento. On the right side there are three poor windows with wooden gratings which face south.[8]

There was no covering on the floor: "It was bare earth, its interior dark."[9] There were at the time ninety-five Indian families with 406 persons living in the pueblo.[10]

Shortly after 1801 Fray José Pedro Rubí de Celis assumed the administration of the mission. Writing in 1808, he noted that "the church was rebuilt with its two new towers,"[11] implying that until that time there had been only the planar facade typical of early postrevolt religious building. In 1782 the status of the church was reduced to that of a visita of nearby Santo Domingo. The control of the church was removed from the hands of the Franciscans in 1823 as the missions were secularized by the Mexican government; but on July 9, 1900, the Franciscans returned to the pueblo, serving San Felipe from nearby Peña Blanca.

Father Jerome Hesse left us with a somewhat ironic and amusing incident of life in San Felipe pueblo and the Indian's relation to the church. It tells of Christmas 1912 and poignantly illustrates the amalgam of native and Christian beliefs at this most sacred of holidays. Like the Christmas story of Isleta by Elsie Parsons (see Isleta), the anecdote also illustrates the relationship between architecture and dance, structure and movement, and prayer and belief. Father Jerome wrote, "I entered the church where I found the altar tastefully decorated. Before the altar the Indians had erected a hut of cedar twigs, covered with a roof of straw." (This was similar to structures built outdoors to house a shrine or serve other religious purposes—for example, the structures built each year as part of the dance on August 4 at Santo Domingo pueblo, erected at the head of the principal dance plaza.)

A dance? in church? before the crib? What a scandal, a desecration, a sacrilege! someone might say. And the benches? Are they removed? Well, there are no benches. . . . The Indians squat on the floor, not even a wood floor, but just Mother Earth. The interior of an Indian church is very bare, at least at San Felipe and Santo Domingo. Four adobe walls, whitewashed within, an adobe roof, generally leaking in places, with an adobe floor: truly not unlike the stable of Bethlehem. A few simple boards nailed together to form an altar, a statue of St. Philip, a few mural paintings to serve as ornaments, and you have a complete Indian church.[12]

If decoration was spare at San Felipe, segments of the church were whitewashed, but whitewashing

20–6

San Felipe, Plan

[Sources: National Park Service Remote Sensing;

and historical photos]

was usually restricted to that segment of the principal facade between the towers or to a wainscot on the interior, while the balance of the church remained the color of the earth. A similar practice is still evident at Picuris, where only the facade is painted white, although the balance of the structure is an earthen color. At Laguna the entirety is white, although it was probably not always so. The whiteness makes a lasting impression in the dusty lands of New Mexico as almost every structure, whether made of earth or not, acquires a chromatic layer of dust that joins it to the countryside.

Although the towers were eroding in 1915, Prince was nonetheless impressed by the brilliance of San Felipe and noted its "dazzlingly white appearance"; he also remarked that "it is cared for most faithfully, being whitened every year until it glistens in the bright sunlight."[13] There were other benefits to whitewashing, which Hesse described in a 1920 article. Hesse was troubled by the two horses painted on the upper balcony of the eastern facade, a motif also present at Santo Domingo and occasionally at other churches. "Horses, stationed at the entrance of a church," he reasoned,

are not very conductive to devotion, so I asked the parishioners to obliterate them through a coat of whitewash. The feast of St. Philip, patron of San Felipe, was near at hand, when, according to "costumbre" (custom) the church is annually whitewashed both inside and outside. The Indians' love for the horse is well known; and "cabellitos" are objects of their superstitious veneration. . . . What happened? The church was simply not whitewashed, for the Indians had no time! Excuses are never wanting to the Indian.[14]

The church of San Felipe is an impressive structure but is more impressive from the flank than from the front. The facades of the Spanish mission churches, other than those of the Salinas district and perhaps Acoma, rarely achieve the scale or proportions necessary for lifting them from their bases. Nor are they integrated into the pueblo in such a way that their increased mass is sufficient to create a striking contrast. In pueblos such as Zia or Laguna, for example, when the pueblo is contemplated as a unit, the church may actually read more strongly from a distance. In these conditions the church, a reflection of native construction method, becomes a part of the architecture of the pueblo, however different the form.

Height was not the means, nor was span the tool to increase the church's volume, and the heights of postrevolt churches rarely exceeded their widths. Length was the sole variable, and with it the church size, determined by the number of the congregation. San Felipe is nearly one hundred twenty feet long, an exceptional dimension for an architectural method that historically had produced living spaces on the order of twelve to fifteen feet square.

As Kessell noted, there are more vigas in place today than at the time of the Domínguez visit, suggesting that the church was extended during the 1801 remodeling, at which time the twin towers were added to the facade.[15] The marvelous photograph taken in August 1919 from the southwest, where the nave is played against the lower convento to the south, illustrates the feel of the long, literally shiplike nave and the characteristic bump of the tapered apse as it rises to accommodate the transverse clerestory. This photo also shows the seriously eroded towers, particularly the pinnacles of the open belfries, which suffered under rain and wind from all four directions. The church was refurbished after 1920, probably on more than one occasion, as it usually appears in good condition in photos.

The images of the horses that troubled Father Jerome still grace the entry facades, although they were missing from a Parkhurst photograph from the 1930s. By that time the convento had all but melted into the landscape, and a small structure (baptistry/sacristy) appended the nave to the north.

With the importation of commercial paints came a greater palette of colors. Today the facade and its wooden brackets are painted in lively hues: turquoise tipped with red. The horses have returned, and the dado and stepped sky altar motif of the wainscot are worked in yellow. Even from the opposite bank of the Rio Grande, the church creates an unmistakable impact.