Santo Domingo Pueblo:

Santo Domingo

1607; 1706; 1754?; 1895 (new site)

Many of the pueblos suffered at the hands of the Spanish or other tribes; for the churches destruction was often caused by the depredations of the Comanche or the Apache. The Salinas missions were ravaged by drought and, like many of the villages, by the communicable diseases that accompanied the Europeans. Santo Domingo, in addition to all these other problems, was also plagued by flood.

There have been four settlements in the vicinity of the current pueblo; the first, called Gipuy by Forrest, lay about two miles east of the present Santo Domingo.[1] It was here that Oñate founded the monastery of Nuestra Señora de la Asunción. This was the second pueblo of that name to exist on the site, the first, tradition has it, having been destroyed by the high waters of the Galisteo River prior to 1591. Gaspar Castaño de Sosa rechristened the village Santo Domingo when he stopped there in 1591. Both the pueblo and early efforts to found a Catholic mission there were dashed by floodwaters again in 1605. A new village, almost coincident with today's Santo Domingo, was founded shortly thereafter, moved further eastward as its western edge was lost to the river.

A new church structure arose in 1607 under the direction of Juan de Escalona, and in 1619 Santo Domingo became the ecclesiastical headquarters of the province. Relations between the religious and the Spanish civil and military authorities were not always the best during the early seventeenth century. The church precinct was apparently strengthened to such a degree that the friars were charged with constructing fortifications and storing munitions and other defensive supplies within the convento.[2]

Although Santo Domingo was not specifically named by Benavides, he attributed seven pueblos to the "Queres nation, commencing with its first pueblo, San Felipe. It contained 7,000 souls, 'all baptized,' three convents and churches, very spacious and attractive, in addition to one in each pueblo." He credited Fray Cristóbal de Quirós with conducting training in the Catholic faith but also "in the ways of civilization, such as reading, writing, and singing."[3] By midcentury Santo Domingo was said to have "a very good church . . . a choir, an organ, and many musical instruments; its convento was 'good.'"[4] Almost a century and a half later music was still a notable part of the service.

Indian vengeance struck swiftly during the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, and within two days the three priests at the pueblo were killed. Governor Antonio Otermín and his party of refugees passed through the village on their forced flight south and found the church securely locked. They broke open the fas-

19–1

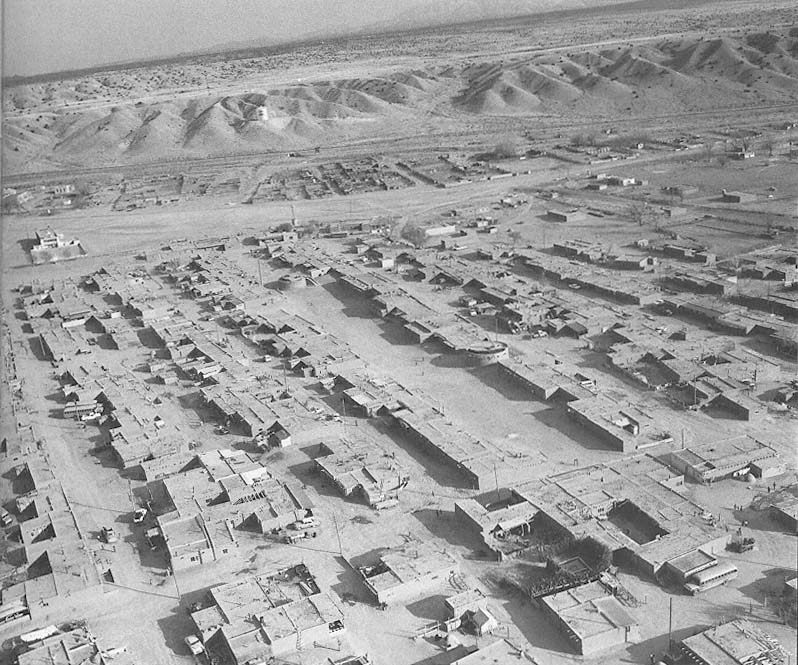

Santo Domingo

Seen from the air, the linear organization of the pueblo is clear. The church is in the upper left.

[Dick Kent, 1960s]

tenings and discovered a large mound of earth in the middle of the nave. Subsequent digging uncovered the bodies of the three missionaries buried in their Franciscan robes. But the physical aspects of the structure stood unmolested, and the retreating Spaniards removed the ornaments, vessels, and pictures and carried them to El Paso del Norte.

To what extent the church itself was damaged is not known, but during the attempt to retake the lost province in the following year, one of the soldiers recorded that

they marched to the pueblo of Santo Domingo where they found things in the same condition as in the others. All the churches had been demolished and burned, and yet in all of them, as had been stated, the Indians' kivas had been built. The apostates had rebuilt the principal stretch of wall (lienzo ) of Santo Domingo for a fortress and living quarters. The Spanish saw in this pueblo a large number of masks and idolotrous objects.[5]

Perhaps, Kubler queried, the church was rebuilt prior to 1696 and ruined in the incidents of that year; or perhaps the remains of the old structure were extended and refurbished in the construction of 1706.[6] The site of the pueblo was shifted to the current location around 1700. Some time after the arrival of Fray Antonio Zamora in 1740—1754 is a date suggested in one "vague" report—a larger church was constructed at the padre's own expense. "Thus in 1776 Santo Domingo had two churches, side by side facing south, an old one relegated to burials and passage to and from the convento, and a thick-walled newer one, both 'in full view of the Rio de Norte,'" explained John Kessell.[7]

Tamarón visited the mission in 1760 and commented more on the state of the souls than on the condition of the structures. The next reports, these in the usual excruciating detail, were those of Domínguez in 1776. "Father Zamora," he began,

built it [the church] out of his alms. It is adobe with very thick walls, single-naved, and the outlook and main door are due south. The choir loft is in the usual place and like those of the Rio Arriba missions, and the entrance is an ordinary single leaf door with a key. It is approached by a stairway of small beams between the walls of the two churches mentioned. This begins from the front corners of both and is open toward the cemetery. In the choir there is a good large niche for the musicians, who, at Father Zamora's expense, keep two guitars and three violins there.[8]

There were only rudimentary furnishings for the church. "For further adornment of the good work which I have been describing, Father Zamora had

19–2

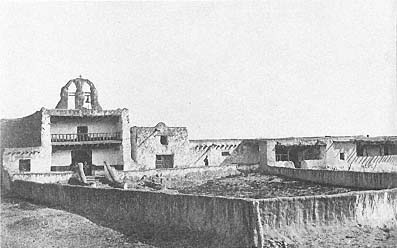

Santo Domingo

1880

In this early photograph two churches—both subsequently destroyed—are

visible. Although suffering from erosion, the bell arch displays an

exaggerated vertical note surpassing that of the old San Juan church.

[Museum of New Mexico]

19–3

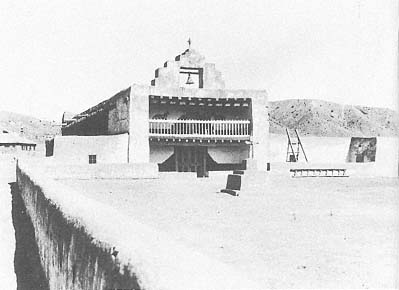

Santo Domingo

1917

Taken away by flood, the new church has been rebuilt in a safer location and

stands in good condition—neatly plastered.

[Museum of New Mexico]

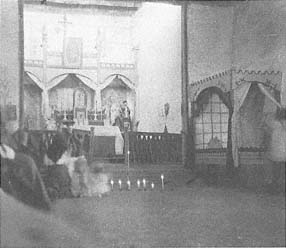

19–4

Santo Domingo

circa 1907–1910

The clerestory is oriented toward the west, receiving

the afternoon light.

[Museum of New Mexico]

a small altar screen in perspective painted on the wall at his own expense. Although it is an ordinary painting in tempera, it is very pretty and carefully done. It is in two sections and does not reach the ceiling."[9] This reredos, which features an image of the patron Santo Domingo carved in the round, had been painted by a father named Camargo and shipped from Mexico.

The plan of the pueblo differed noticeably from the layout of the other pueblos except, perhaps, for a weak formal simultaneity to that of Acoma. Instead of the more typical plaza-centered arrangement, Santo Domingo was, and still is, arranged in roughly parallel linear blocks.

The pueblo consists of six blocks, or buildings, of dwellings. Of these, two stand one after the other below the right corner of the new church, and face due east overlooking the church and convent to their left side on the north and to the south side on their right side. The four remaining blocks face due south with their backs to the church and convent. They are all separate from one another, with a street in the form of a cross dividing the four.[10]

There was, however, a plaza in the pueblo: "The houses have upper and lower stories like those I described at Tesuque, and these are better arranged than the ones there, with a beautiful plaza overlooked by the last ones mentioned between their facades and those of the church and convent."[11]

An 1880 plan by Bandelier is reproduced as Figure 51 in Kubler's The Religious Architecture of New Mexico and depicts this arrangement in basically the same position, although the supposed beauty of the plaza is difficult to glean from Bandelier's sketch. The depredations of the Comanche and other Plains Indians had on rare occasions penetrated as far as the Rio Grande valley, and so, as at Taos, "the whole pueblo is surrounded by a rather high adobe wall with two gates; this is for resistance against the enemy [Indians], for day by day they show more daring against the natives of this kingdom."[12] Fray Juan Agustín de Morfi was warmer in recording the conditions in 1782: "The church is large and beautiful and attractively decorated and painted. The house of the priest is roomy and comfortable."[13]

When the American Zebulon Pike was escorted from Santa Fe to Chihuahua for interrogation, he had the opportunity to stop at Santo Domingo. He described his visit in a diary entry dated Friday, March 5, 1806, and did so in a rather casual tone, considering the harsh conditions in which he was traveling: "When we entered it [the church], I was much astonished to find enclosed in mudbank walls many rich paintings, and the Saint (Domingo) as

large as life, elegantly ornamented in gold and silver. . . . We then ascended into the gallery, where the choir are generally placed to procure the charming view frequently mentioned by visitors."[14] An unsigned 1806 inventory stated that the church had "just been repaired, well roofed with boards, the vigas very striking with their corbels and carved decoration."[15]

The church occupied a site nearby the bank of the Rio Grande, that is, northwest of the pueblo. In time the church sat directly on the banks of the river, which continually wore away at the available land. A mission report of 1831 listed floodwaters in 1780, 1823, and 1830 when two unnamed churches were lost.[16] The threat was relatively constant. John Bourke mentioned the heavy rains of the summer in 1881 in several of his journal entries, often adding that repairs to the church were necessary as a result. His sketch of the old Santo Domingo presented the structure much as its successor appears today, except that the gable then sheltered two bells instead of one.[17] In 1881 through 1884 the very existence of the structure and the western part of the pueblo was continually threatened by the river's waters. On each occasion, with levees built to protect the building and a last-minute subsiding of high waters, the church was spared. In 1885 the last grace period expired. The Santa Fe New Mexican Review ran a headline in 1885 exclaiming, "The Raging Rio Grande Is About to Take the Church at Santo Domingo." And then it finally happened: on Thursday, June 3, 1886, the river reached the church and began its destructive undermining. First to go was the main new church, then the old one, and finally the convento. Anything that could be removed had been removed, including all mobile ornamentation, paintings, and other furnishings. The earth structure of the buildings succumbed to the turbulent waters and became part of the riverbed or bank or was carried downstream.

Father Noel Dumarest, a young French priest, was assigned the custody of Santo Domingo on January 1, 1895, as part of his ministry at Peña Blanca. Through his prompting a new church was constructed, this time safely east of the pueblo on rising ground. It maintained the traditional ground-hugging adobe nave with a twin-towered facade, and although a new structure, it immediately occupied a comfortable position in the community. Given the ravages of Archbishop Lamy's campaigns for putting archdiocese architecture in a more "polite" style, it does indeed seem a wonder that the church was built in the usual manner. "Judging from the improvements upstream at San Juan,"

19–5

Santo Domingo, Plan

[Sources: National Park Service Remote Sensing;

and historical photographs]

John Kessell succinctly put it, "one might have expected the new Santo Domingo church to rise with peaked windows, gabled roof, and slender white steeple."[18] Somehow the building escaped this fate. Perhaps Dumarest was in no bargaining position as to style—he was both too young and too new on the job—or maybe the traditional ways of Santo Domingo pueblo forced continuity rather than innovation.[19]

The church of Santo Domingo is rather small in comparison to, say, San Felipe nearby, but the congregation at the time the building occurred was probably smaller. Domínguez listed the population of the village in 1776 as 136 families with 528 persons,[20] and the population had not drastically changed in the intervening century.

The last church, like its predecessors, is a single-naved structure. The choir loft above the entry to the nave continues a spatial sequence that begins between the towers. Because of the building's orientation to the west, the effect of the functioning clerestory is felt only in the afternoon when the declining sun directs its light on the altar. The windows on the south side of the nave, however, somewhat counteract the effect of the limited clerestory light.

The sanctuary is inset, raised, and articulated, but it is not battered inward as at several other pueblo churches. A lively, three-part altarpiece dominates the front of the church and illustrates the continuing tradition of santos in New Mexico. Free and simple, the colors and painting techniques derive their effect from feeling in gesture rather than sophistication in modeling. The lattice altar rail and several other details, like the frames of the reredos, reflect the Victorian penchant for ornamentation, rather than the simple and direct execution of traditional construction.

On the exterior the principal, western facade is composed of two towers with a balcony between, much in the manner of nearby San Felipe or the rebuilt Cochiti. But unlike the earth tones of most of the church, the western elevation is rendered more emphatic by the use of white and color. Painted decorations exhibiting the same feeling as woven patterns are painted over the white background. The large beams that span the opening (in 1982) are colored in green, white, and red; the geometric designs are intricate and handsome and reinforce the presence of the main doorways. A stepped motif integrates the dado wainscot with the frame around the lower and upper balcony doors. Also on the balcony are the two familiar horses that Hesse tried in vain to have eradicated with whitewash (see San Felipe).

One enters the church through the enclosed campo santo at the west of the church. Earthen and bare except for a single wooden cross, the enclosed court marks the collective summation of the hundreds of graves on this site or on that land once west of the pueblo reclaimed by the river.

Writing in 1929, Earle Forrest noted that each year at the fiesta on August 4 the church was put in order: "It is cleaned and whitewashed, and two large horses are painted by native artists on the front [of the church]."[21] The annual dance is still held in August, and it has grown into one of the main attractions of the summer season. Several hundred dancers may participate, and a crowd of thousands fills the pueblo. There is a strange mixture of cultural institutions at this time: the Anglo tourist, often in strange garb; the commercial aspects of the fair; the amusement park rides and snocones; the presence of the faithful at the church; and, of course, the dancers emerging from the kivas clad in costumes that date back centuries. A curious, sometimes tawdry blend, it directly reflects the juxtaposition, or collision, of the cultures and values from which New Mexico has been fashioned.