Cochiti Pueblo:

San Buenaventura

pre-1637; c. 1706; c. 1900; 1960s

At the bottom of the basalt flow that extends southward from Santa Fe, where the Rio Grande cuts deep into the terrain, lies the pueblo of Cochiti. Always aware of the surrounding mesas, today the community is further dwarfed by the great earthen dam that has transformed the Rio Grande behind it into a shallow lake. But the river squeezes through the sluices and then comfortably flows once again through the cottonwoods and shrubs that surround the pueblo. Earle Forrest described Cochiti in 1929 as a nearly perfect pueblo: "Cochiti contains everything that goes to make an interesting pueblo; an ancient catholic mission in charge of a priest from Peña Blanca, two large kivas where members of the Turquoise and Calabash clans still strive to keep alive the religion of their fathers in spite of the fact that most of these indians are catholic, and a picturesque plaza in the center of the village."[1] The scene, alas, is not as perfect today, nor is there a marked consistency to the buildings of the village.

The pueblo, as the northernmost of the Keresan group, claims its origins in the Tyuonyi and Frijoles canyons, where the early dwellings were enlargements of natural caves dug in the soft tufa stone (now part of Bandelier National Monument). Subsequent settlement was invested in two or three separate locations before the group eventually split in two, forming the pueblos now known as San Felipe and Cochiti. Other linguistically related Keres speakers include Santo Domingo, Zia, Santa Ana, and the western pueblos of Acoma and Laguna. Bandelier claimed that Cochiti was one of the group of eight Keresan pueblos named by Pedro de Casteñeda, the chronicler of the Coronado expedition.[2] In the fall of 1581 the Chamuscado-Rodríguez expedition was supposed to have reached the pueblo, described as having 230 houses of two and three stories and named Medina de la Torre.[3] The following year the Espejo expedition also stopped at Cochiti and described the people as being "very peaceful." They provided the Spaniards with foodstuffs such as turkey and maize and traded skins for iron goods.

The date of the mission's founding is not known, but Forrest assumed it to be early in the 1600s, the same as the nearby Nuestra Señora de la Asunción monastery associated with San Felipe Pueblo.[4] Benavides mentioned Cochiti but only as one of three churches and conventos serving the "Queres Nation."[5] Throughout the seventeenth century, Cochití remained a visita of Santo Domingo mission, although in 1637 the presence of a resident friar was noted.[6] In 1642 Cochití was said to "have a church."[7] A 1667 reference was the first to attribute the mis-

18–1

San Buenaventura

1890s

The balcony stretching between the extended side walls was sagging noticeably at the turn

of the century.

[Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives]

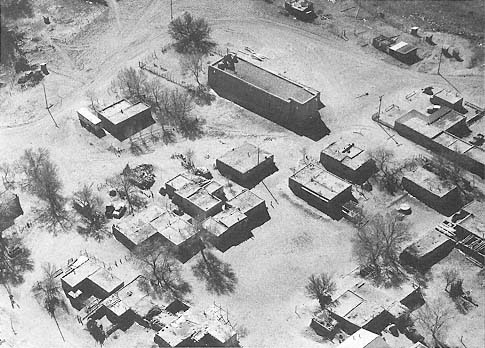

18–2

Cochiti Pueblo

A portion of the pueblo from the air.

[Dick Kent, 1960s]

sion name to San Buenaventura, who remains the patron saint.

The early church building no doubt followed the prototype for its time and location: thick adobe walls, a single nave, a flat facade with a small arch for a bell, a beamed ceiling, and perhaps a clerestory. Although the pueblo was a "storm center" (as Prince called it) for the great revolt of 1680, no priest died there.[8] Legend has it that warned by an Indian believer, he managed to escape the pueblo. What happened to him thereafter is not known. But if the mission was a visita of Santo Domingo, there might not have been a priest in residence. In 1681 the abortive Spanish attempt to reclaim New Mexico reached Cochiti but found that the pueblo, with the warriors from San Felipe and Santa Domingo, had fled to Horn Mesa, which rises about seven hundred feet above the village. Again in 1693—the Reconquest—the Indians withdrew and fortified an adjacent hilltop but were coerced by the Spanish to peacefully return to their fields and pueblos. The peace did not last. In April 1694 Vargas returned to find the Cochiti people once again entrenched on the mesa top.[9] This time efforts toward peaceful negotiations were unsuccessful. The outcome was that the few Spanish, augmented by forces from the now pacified and allied San Felipe, Santa Ana, and Zia pueblos, stormed the summit and took the battle, large stores of food, and many captives.

The prerebellion church lay in ruins, and Vargas ordered a new church built in place of the old. How much was constructed before the subsequent revolt of 1696 is not recorded, but in 1706 the mission was still, or again, in poor condition. Fray Juan Olvarez reported, "This mission has a broken bell without a clapper. (The Indians took all the clappers away, to make lances and knives.) There is one of the ornaments which his Majesty gave. The vials are a silver one, another of tin plate. The church is being built. This mission has about five hundred and twenty Indians. . . . It is called San Buenaventura de Cochiti."[10]

Whether this meant, as it often did, that the roof was being replaced, or that work from 1694 or post-1696 continued, is not certain. Bishop Tamarón in 1760 left no description of the physical structure, although he had only mixed reactions to the parishioners: "The catechism was put, and the Indians were prepared. They do not confess and are like the rest." There was a priest in residence at the time of Tamarón's visit, and the population stood at 450 persons.[11]

A decade and a half later Domínguez summed up his remarks by calling the interior "very gloomy." Once again he sought in vain the brilliance of the central Mexican religious interior. "The church is adobe with walls about a vara thick, single-naved, with the outlook and the main door due east."[12] Unlike today's church, the nave continued to the apse with no diminishing of width and did not include a choir loft. A clerestory and two "poor" windows facing south illuminated the interior. "There is a little belfry over (the main door) with a good middle-sized bell that the King gave."[13] "Adjacent to the church on its south side, there is a porter's lodge, which is a very pretty little portico to the east without pillars in front of it because it is very limited. The floor of this little portico is paved with small stones like those mentioned. There are adobe seats around this room, and the door is in the center of the wall."[14]

Rounding out the list of major structures was the corral, often an integral part of the religious complex. Here was kept the friar's stock as well as his means of transportation. "The corral is against the convent on the south, runs from the upper to the lower corner and is about 8 varas wide. It has a rather high adobe wall and a great two-leaved door without a lock to the east. Against the south wall in the corral are stable and strawloft, both very large rooms."[15]

The "very gloomy" church remained in eighteenth-century form until past the turn of the century, when its condition showed signs of grave deterioration. As was often the case, the neglect of the church's maintenance led to major repairs, in turn suggesting a considerable rebuilding or updating in style. Although not the resident priest, Fray Francisco de Hozio wrote to Governor Facundo Melgares in 1819 requesting that the governor aid in securing the services of a certain mason named Madrid who lived near Santa Cruz. "I have arrived here without incident and found this church in a state that caused me much sorrow since with the greatest ease it could have been finished by now. . . . I beg you therefore, by virtue of your authority, to make Madrid come and lay the adobes there are. Indeed I am of the opinion that with two days work it will be to the bed molding."[16]

The content of the letter suggests that the church was unroofed at the time, at least in sections, and that the replacement of the vigas was awaiting the final courses of adobe bricks. It seems curious that with the resources available to the Indians of the pueblo, their long experience with adobe, and the considerable sections of the church walls still remaining that the father felt it necessary to call on a Spanish or mestizo mason from fifty miles away.

18–3

San Buenaventura

circa 1900

The interior of the church with its raised sanctuary.

[Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives]

Perhaps there had always been continual reliance on the building skills of the Spanish colonists in the construction of large edifices such as churches. Perhaps the construction was always under the supervision of a builder rather than the missionaries themselves. Or perhaps the Indians were just not interested.

In any event three days later the governor ordered the alcalde of Santa Cruz de la Cañada to send "the mason Madrid under appropriate guard to Cochiti to build up the church, on the basis that he should have done it already."[17] The work apparently was done. Kessell suggested that some major modifications to the building fabric were undertaken at this time: the narrowed chancel, the two towers, the shallow balcony, and the choir loft that had not been in its "usual place" to greet Domínguez.[18]

The remainder of the century passed uneventfully. Nevertheless, when Lieutenant John Bourke visited the church in 1881, he wrote:

The church of [San Buenaventura at] Cochiti [is] very old and dilapidated; the interior is 40 paces long to the foot of the altar by 12 broad. It is built of adobe and whitewashed on the inside—Altar pieces showing signs of age—swallows making their nests in rafters. Ceiling of riven slabs, nearly all badly rotten and those which had been nearest the altar have been replaced by pine planks covered over with Indian pictographs in colors—red, yellow, blue & black. Buffalo. Deer, Horses, Indians, Indians in front of lodges, X [cross] and other symbols. Olla used for holy water font. The cross had fallen from the front of the church and its whole appearance is strongly suggestive of decrepitude and ruin.[19]

Early photos from 1889 and 1900 by Vroman and others show the church in the condition Bourke described. The plaster has eroded, the walls look beaten, and the large beam that supports the balcony on the eastern front groans under the weight of its load. Vroman's interior photo, however, depicts a tranquil world in repose: the interior is empty, there is a bare earthen floor, and the altar-piece, flanked in symmetrical balance by two smaller paintings, fills the sanctuary. The walls, whitewashed and stained with a darker dado, support the tin candle holders Prince claimed originated in Chihuahua. The ceiling of the chancel is painted "grotesquely . . . with geometrical figures in high colors, red and yellow and black, while representations of moons, horses, etc., are interspersed without any apparent design."[20] The soft light that falls on the altar attests to the presence of the clerestory. Although the exterior is sadly deteriorated, the interior seems to be holding its own.

18–4

San Buenaventura, Plan

[Source: Kubler, The Religious

Architecture ]

But then in 1900 Austrian Franciscans took custody of the church, and the strong winds of change began to blow. Of course, repairs were necessary, but the forms these repairs took were unduly severe and rather insensitive. No doubt the fathers believed that this was an opportunity not only to repair the church but also to update its style as well. If San Felipe and Santo Domingo were spared the trauma of remodeling, Cochiti, although administered by the same custody at Peña Blanca, suffered the imposition of an imported architectural style. The walls were patched and replastered, and a pitched roof of corrugated metal was erected over the entire church. Topping it in good Anglo fashion was a steeple some twenty feet high. At the front a portico of three arches replaced the open balcony/ narthex—arched forms that would have been more comfortable in California, having been almost nonexistent in New Mexico. Photographs from this period portray a building so drastically revised that it would be almost impossible to match it with the form of the preceding structure. Of course, this was no doubt the intention—to create a distance between the "new" church and its predecessor. The steeple, however, caused structural problems. From the beginning its height exaggerated its wind-catching propensity and threatened to seriously crack the walls below. In short order it was lopped off to a truncated stump.

Even at the time of the remodeling in 1910, there must have been some outcry from those beginning to appreciate the rapidly deteriorating Hispanic colonial heritage in New Mexico. They were addressed directly by Father Jerome Hesse, who wrote about the remodeling in 1916 with a great sense of pride and righteousness:

The appearance of the old, venerable church of the pueblo has been changed completely, to the chagrin of the archeologists, it is true, but to our own great pleasure and satisfaction. Some years ago the mud roof was replaced by a substantial roof of corrugated iron, and last year the interior of the church was renovated and decorated. First of all the bumpy, crooked walls had to be made as even as could be done before plastering; then the damp floor of clay had to make way for a regular wooden floor; moreover, through the inventive genius of our Ven. Brother Fidelis, the rough logs of the ceiling were hidden by a selfmade, cheap but handsome ceiling; finally the interior was tastefully decorated. . . . The whole interior of the church underwent a complete change and assumed a rather modern appearance.[21]

If there was ever a succinct statement of the conflict between Anglo and Indian or Hispanic values, this must be it.

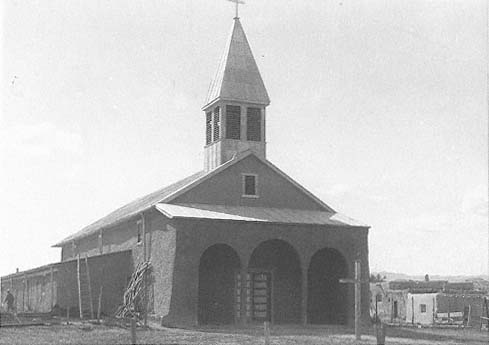

18–5

San Buenaventura

circa 1915

A three-arch porch has replaced the balcony, and the church wears a disproportionately

tall steeple.

[Museum of New Mexico]

18–6

San Buenaventura

1949

In response to the threat of structural failure, the tall steeple has been trimmed, helping return

the building to the earth.

[New Mexico Tourism and Travel Division]

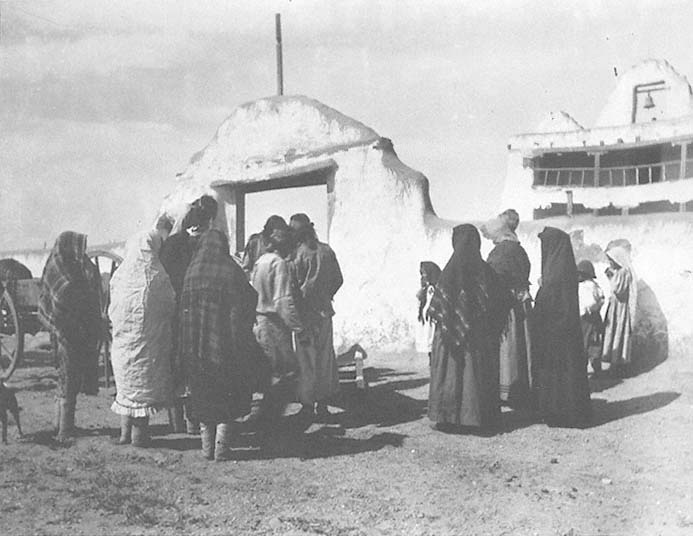

18–7

San Buenaventura

A funeral pauses at the entry to the campo santo.

[Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, F. Starr Collection, 1894–1910]

The archaeologists, and most of the writers, however, were not happy. In 1918 Paul Walter responded, "The beautiful Cochiti mission church . . . has been unfortunately transformed into a nondescript chapel with a huge tin roof and an arched portal, evidently an attempt to mimic the California mission style."[22] In 1929 Forrest was no kinder.

The modern destructive spirit which has ruined several of New Mexico's ancient monuments reached out its hand to Cochiti, and a few years ago the exterior of the old edifice was so altered that it looks more like a visitor from some eastern hamlet. This is the only discordant note in an otherwise perfect Indian pueblo. The old flat roof and picturesque Franciscan belfry have been replaced by corrugated iron and a high pointed steeple. The balcony was removed and the entrance was enclosed by an adobe porch with three arches, the only attempt at ornament.[23]

To those extolling the greatness of the missions as they were, the remodeling was a sacrilege. Fray Angelico Chavez, noted authority on the missions, discussed a re-remodeling with pueblo authorities as early as the 1930s,[24] but the actual work waited until the mid-1960s when Santa Fe architect Robert Plettenberg prepared the design of the current structure based on old photographs and descriptions. Certainly the result is happier than the Victorian revisions, although new construction can hardly restore the old quality, which is the product of years. While the facade reasonably approximates the look of the church prior to 1910, elements of the bell arch and beam work are turned comments on the old. The use of a hard cement stucco is another expedient: no covering material for adobe walls produces the same properties as mud plaster, whose deterioration acquires character over time, unlike the sadness of cracked and chipped stucco. The restoration, like the reconstruction at San Ildefonso, is comforting to some extent. Perhaps as time operates on this new building, and it is patched, augmented, and eroded, even in stucco, it, too, will acquire a patina of significance.

Earle Forrest was still moved by the simplicity and the beauty of the Catholic mass at Cochiti on July 14, 1929, at the time of the annual festival:

During the morning, mass is held in the old mission by a priest from Peña Blanca. The service is typically indian, and when you enter the church you step back across the centuries to the old Spanish days. Kneeling in the nave, which is without seats, the men on one side and the women on the other, are the indian neophytes with bowed heads listening to the blackgowned padre as in the days of old, while an indian choir sings at intervals from the gallery above.[25]

Cochiti today lacks the architectural coherence it possessed historically, even until early in this century when it was described as "the nearly perfect pueblo." The changes in the job market, the construction of federally sponsored detached houses at the periphery of the pueblo, and the impact of recreation and new development spawned by the Cochiti Dam have all taken their toll. But there is still a quality to the place, and to all pueblos, that speaks of a connection with the past and a connection to the earth.