The Pueblo Rebellion

Traditionally, the Pueblo tribes had lived as independent units governed by their own councils. Even among groups that shared the same language, mutual tolerance, rather than political union, was the general practice. But resistance to the Spanish had been building. The colonists' demand for additional fields and pastures at times forced the Indians to relocate, often to land less convenient or less fertile. Late in the 1670s, under the instigation of Popé from San Juan and several other influential leaders from the northern pueblos, the resentment that had been smoldering for a century finally ignited. A native informant recalled:

Popé came down to the pueblo of San Felipe, accompanied by many captains from the pueblos and by other Indians, and ordered the churches burned and holy images broken up and burned. They took possession of everything in the sacristy pertaining to divine worship, and said that they were weary of putting in order, sweeping, heating, and adorning the church; and that they proclaimed both in the said pueblo and in the others that he who should utter the name of Jesus would be killed immediately; and that thereupon they could live contentedly, happy in their freedom, living according to the ancient customs.[31]

On August 10, 1680, the rebellion flared; the Spanish were either killed or forced to flee south to El Paso. Twenty-one Franciscan friars died in or near their churches; four hundred colonists were slaughtered. The Indian victory was swift and complete: the first loss of a Spanish province in the New World.

Life without the Spanish did not prove easy, however, nor was the confederation of pueblos an administrative success. "Scarcely a Pueblo alive in 1680 could remember how affairs had stood before the Spaniards had brought them cattle and sheep, exotic vegetables and grains, iron hardware, and a new religion."[32]

For twelve years the Indians retained control of the country. In 1691 a preliminary expedition attempted to reclaim the province, but this effort proved premature. Finally, however, under the

1–7

Plaza Del Cerro

Chimayo

The best preserved of the fortified plaza town plan.

[Dick Kent, mid-1960s]

1–8

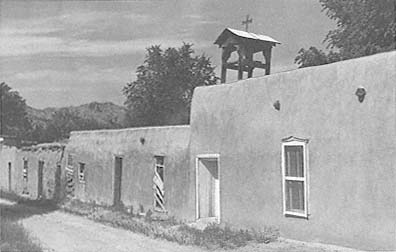

Ortega Chapel

Plaza del Cerro, Chimayo Only the small wooden belfry identifies this

particular cell as serving a religious function.

[1984]

leadership of Diego de Vargas, New Mexico was retaken during the campaigns of 1692–1693. Given the hostilities of 1680, the Reconquest was swiftly accomplished. Vargas retook the capital in 1693, and Spanish rule was reinstated at the same Palace of the Governors from which the Spanish had fled twelve years before. Relations between the military and the clergy were still strained. In one case, the military purposely provoked the clergy by saying the kachina images (of Pueblo deities) were harmless and allowing the Pueblos to maintain possession of them. This taunting was a familiar practice with a long history. In 1661, for example, one priest recorded "that once when there was a great deal of snow the catazinas (i.e., kachina) Indians went up to the flat roof of the very church and began to perform their superstitious dance very noisily."[33]

During the insurrection, the Indians had in most cases simply torched the roofs of the churches, as if this act alone were enough to deconsecrate these buildings and remove them from the Christian province. Laying adobe walls was time consuming, and if they were still standing, why not use them to good purpose: as a corral, for example? With the Spanish return, the church walls were repaired or rebuilt, and new roofs were constructed. The Pueblo Revolt marked a turning point in the history of virtually every existing church structure in New Mexico, thereby making problematic questions of origins, dating, and formal evolution.

In 1696 a second revolt flared but was quickly quelled. For the most part the colony—both Spanish and Indian alike—settled thereafter into maintaining its existence. Bishop Pedro Tamarón y Romeral undertook an inspection in 1760 and was appalled at the state of both clergy and religion in the province. Sixteen years later, Fray Francisco Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante made a two-thousand-mile voyage of exploration and investigation. As an official visitor , Domínguez left an excruciatingly detailed description of mission architecture and native ethnography; his inventory of even the smallest object suggests the paucity of the missionary program in general and church holdings in particular. Domínguez's Description of New Mexico provides an invaluable document for examining the state and use of the churches of the province at the end of the eighteenth century.

Almost from the very beginning, the regular church had continually attempted to wrest control of the New Mexican religious project from the Franciscans, who had been granted its jurisdiction. Finally in 1797, under renewed pressure from the bishop of Durango, the towns of Santa Fe, Santa Cruz, and Albuquerque were secularized, which placed the churches under the direction of parish priests rather than Franciscan missionaries.