Ranchos de Taos:

San Francisco de Asís

c. 1815; 1967; 1981

For most Christian churches the facade is the principal architectural subject. Here is the ceremonial face of the church, its entrance, a surface to be embellished [Plate 14]. Often situated prominently on the plaza, the church occupied that zone between the mundane world of the body and the sacred world of the spirit. And although the east facade of San Francisco de Ranchos de Taos fronts the remnants of its plaza—strong, handsome, and noted in its own right—the rear of the church with its celebrated buttresses has become an icon of New Mexican religious buildings.

The notoriety of this particular apse stems primarily from the photographs of Paul Strand and Ansel Adams and the paintings of John Marin and Georgia O'Keeffe, who for many years lived and worked in nearby Abiquiu. But from the 1920s onward a host of artists, many from the northeastern United States, also gravitated to New Mexico, impressed by the area's climate and clear light. They sought the light that graced southern France, the intricacy of the native decorative motifs, or the noble people themselves as working subjects.[1] In the prismatic forms of the pueblos and adobe construction these artists found formal sympathies with the planar concerns of postimpressionism and cubism. And the nascent art deco style, popularized by the Paris Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts of 1925, could readily incorporate the geometric designs and colors of Indian weaving and pottery decorations.

O'Keeffe wrote, "The Ranchos de Taos Church is one of the most beautiful buildings in the United States by the Spaniards. Most of the artists who spend any time in Taos have to paint it, I suppose, just as they have to paint a self-portrait. I had to paint it—the back several times, the front once. I finally painted a part of the back thinking that with that piece of the back I said all I needed to say about the church."[2] The fragment does convey a sense of the whole: its mottled color, the texture of the earthen wall surfaces, the striking profile against the sky, and the mass of the buttresses.

Near Taos the Sangre de Cristo Mountains pull back, revealing a large and fertile plain. Watered by the Rio Grande and its tributaries, this land has been occupied as the northernmost settlement of Pueblo culture for at least seven hundred years. The Spanish followed the Indians, settling in proximity to them not only to facilitate religious conversions and provide a source of labor on their ranches but also to occupy reliable agricultural lands. One of Coronado's party, Pedro de Alvarado, "discovered" the Taos pueblo and valley in the great expedition

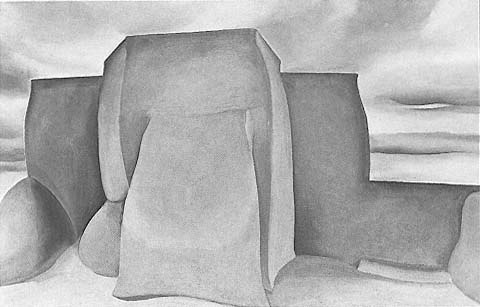

15–1

Ranchos Church, Taos, New Mexico

Georgia O'Keeffe, 1930

This painting has helped make the apse of the structure an icon of southwestern

architecture.

[Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas]

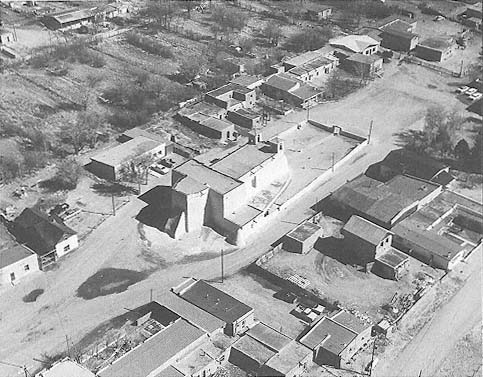

15–2

Ranchos de Taos

The plaza loosely retains the configuration of the fortified plaza.

[Dick Kent, 1960s]

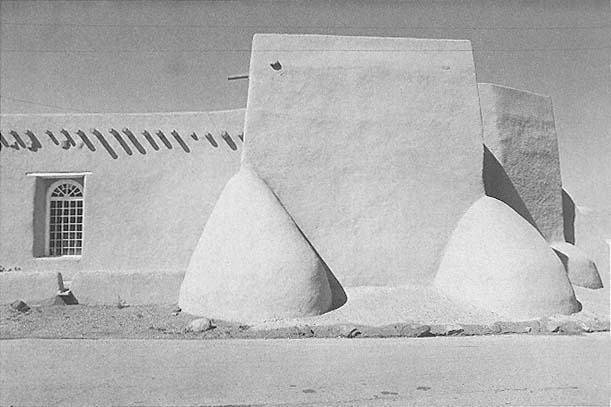

15–3

Ranchos de Taos

The play of curvilinear and planar forms in adobe.

[1981]

15–4

Ranchos de Taos, Plan

[Sources: Kubler, The Religious Architecture , 1940, based on HABS; and field observation by Susan

Lopez, 1986]

of 1540, as it moved toward the northeast in search of the legendary Quivira.

With permanent settlement in 1598, missionary activities commenced. Fray Francisco de Zamora, who accompanied the Oñate party, established the mission of San Jerónimo at Taos pueblo further north, although it lasted under his care only for several years. Not until the 1620s did the undertaking achieve greater stability. The colonists settled on the fringes of the pueblo and even a century and a half later were reported to be living inside the pueblo's walls as protection against Comanche incursions. In the 1620s New Mexico's Catholic enterprise was reformed as the Custody of the Conversion of Saint Paul, and Fray Alonso de Benavides assumed the leadership, bringing with him into New Mexico an additional twenty-seven friars.

Certain aspects of the origins of Ranchos de Taos, south of the pueblo, are not precisely ascertained. Some would like to believe that the church itself dates from as early as 1730. Kubler, citing Hackett, established that there was Spanish settlement on the land as early as 1742.[3] Bishop Tamarón, visiting in 1760, mentioned only the church and settlement at Taos pueblo and noted that there were thirty-six European families included within the parish.

Domínguez, during his 1776 visit, wrote of Trampas de Taos, the site of the present Ranchos, "The settlement consists of scattered ranchos, and their owners are the citizens who live in the pueblo."[4] The plaza apparently had not been built by this time, nor was there a church. If there had been a religious structure prior to the post-Domínguez church, it was probably a private chapel—ermita or oratorio —and would probably have shared the dimensions of one of the transepts of the current church rather than its nave. Parallel origins have been proposed for the Conquistadora chapel at the Cathedral of Saint Francis and the Rosario chapel, both in Santa Fe.

The peripatetic friar explained that settlers not living in the pueblo had established a small plaza (town) near its western side. They were unable to hold their own against the depredations of marauding Indians, however, and retreated within the stronger walls and more secure numbers of Taos pueblo. This arrangement would not last indefinitely,

but only until the plaza which is being built in the cañada where their farms are is finished. This is being erected by order of the aforesaid governor . . . so that when they live together in this way, even though they are at a distance from the pueblo, they may be able to resist the attack the enemy may make. These settlers are people of all classes. Some are masters, others servants, and others are both, serving and commanding themselves. They speak the local Spanish,

15–5

Ranchos de Taos

The interior in the mid-1980s.

[Vicente M. Martínez; courtesy of San Francisco, Ranchos de Taos]

and most of them speak the language of the pueblo with ease, and to a considerable extent the Comanche, Ute, and Apache languages.[5]

The population stood at sixty-seven families with 306 people.

Juan Agustín de Morfi wrote in 1780 that "the settlement forms a square plaza, very capacious. Its houses were almost finished in 1779 with towers at proportionate distances for their defense."[6] His description implies that the houses forming the plaza's peripheral construction included a number of torreones, round tower forms that served as an observation platform as well as a last bastion of defense.

Domínguez's report, and de Morfi's thereafter, served to discredit the theory of a settlement earlier in the century, that is, settlement in the form of a chartered community. Thus, it is believed that the plaza was constructed some time between 1776 and 1780, with the church following shortly after the turn of the century. Tree ring studies made by W. S. Stallings in 1937 yielded a date of 1816 plus or minus ten years. About that time Ignacio Durán petitioned the provincial custos to have Fray José Benito Pereyro minister to the community as well as Taos pueblo, to which he was assigned.[7] The Santa Fe archives contain a copy of the permission to build the church dated September 20, 1813, and Pereyro stated that in 1818 the church was completed. Vigas were alleged to have been found with the carved dates of 1710 and 1718, however. Pereyro, who left Taos in 1818, wrote that "this temple was constructed at the cost of the Reverend Father minister Fray José Benito Pereyro and the citizens of the plaza."[8] The church was substantially complete by the end of 1815, when permission was sought to permit burials within the consecrated space of the nave. The altar screen, by Molleno, appeared on one inventory from 1818 and is still found within the church.[9]

Matt Field, traveling in New Mexico around 1840 in spite of the dearth of travel arrangements, commented on the state of the community: "This town called the ranch lies at the base of a gigantic mountain and is watered by a swift stream that rushes from the ravine we have just mentioned. It contains about 300 houses, and these are built completely together, forming a wall, enclosing a large square, in the center of which stands a church."[10]

The buildings of Ranchos de Taos were constructed in the form of a fortified plaza, that is, as a ring of buildings of relatively thick adobe walls constructed contiguously. Other examples of the village type include Las Trampas and Chimayo, which still exists in a nearly perfectly preserved form. At Ran-

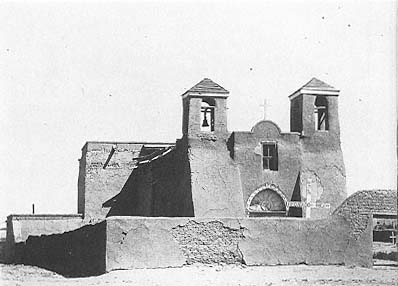

15–6

Ranchos de Taos

circa 1916–1918

The twin towers were trimmed with wooden caps to protect them from the

elements, although in spite of these precautions, the mud plaster is

separating from the adobe bricks.

[Museum of New Mexico]

chos de Taos the church may have formed the western edge of the plaza—certainly its apse wall and buttresses were sufficiently thick to withstand attack.

The church of San Francisco is built in the cruciform plan type more common to the later Hispanic village churches. A good-sized church for New Mexico, it extends about one hundred eight feet in length within the nave, suggesting a significant congregation at the time of its construction. The sanctuary is elevated above the remainder of the nave by three steps, and the church fills out the normal pattern by including a choir loft ("in the usual place," as Domínguez would say) and a clerestory. The northeastern transept, which now serves as a subsidiary chapel, may continue its original use.

The walls are constructed of adobe and measure nearly six feet in average thickness. As mentioned, the enormous buttresses that prop the northeast transept and the rear of the apse have become signatures for the church. On the southeastern facade facing the plaza are two buttresses that support the tower, although these are not structurally bonded to the wall itself, which suggests that they were added at a later time. Diagonal wooden braces shoulder the main viga spanning the chancel area and recall similar braces once seen on the exterior of the Pecos church. There are two windows, one on either side of the nava, although these have been greatly enlarged. Some time after the importation of milled lumber that followed the railroad late in the nineteenth century, the window openings were enlarged. The rounded window heads, inset beneath traditional wooden lintels, appear almost Neo-Romanesque and may exemplify influence from the new cathedral in Santa Fe[11] [Plate 18].

Early photos beautifully capture the texture of the mud plaster applied to the exterior of the church. To retard the rapid erosion of the adobe belfries, wooden caps were installed on the tops of the two towers by the middle of the 1910s. At that time the posts in each of San Felipe's towers' four corners were severely eroded, resembling the earlier forms of both the Ranchos church and the Santuario at Chimayo. By 1918 the mud plaster had begun to spall, but in 1919 or thereabouts the church again sported a new coat of plaster and a protective sheathing of wooden boards over the towers. During the 1930s the church was reroofed and additional repairs were made.

Mud plaster as well as its adobe base is an unforgiving material. Once it has been neglected for an undue period of time, restoration is difficult without considerable attention and prolonged effort. Traditionally mud plaster was touched up each year

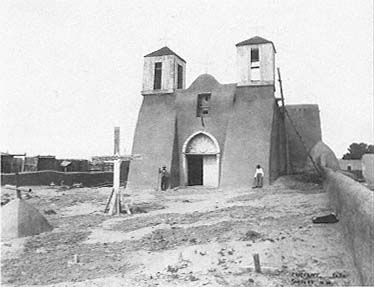

15–7

Ranchos de Taos

circa 1920s

Freshly plastered, the buttresses bring the facade softly to the ground.

Wooden shuttering sheathes the bell towers.

[Aaron B. Craycroft, Museum of New Mexico]

and repaired every two years. This continued maintenance represents considerable investment of time and effort and, more recently, money.

By the late 1960s the Ranchos church was again in need of plastering, and this time the church committee thought it would be better to apply hard (cement) plaster to the walls to "avoid" the problem of continued maintenance. Architect Van Dorn Hooker was asked in 1966 by the governing body to report on the church's physical condition. Working with architect George Wright, Hooker prepared a report for the archbishop that outlined the problems in the church as well as the range of possible approaches to their remedy.[12] They found not only that the walls were badly deteriorated in places but also that portions of the floor decking—and even the ends of some vigas—were severely rotted. They recommended four possible restoration strategies to the archdiocese: (1) abandon the church (and there had been some talk that the building was too small), (2) give it to the National Park Service to become a monument, (3) partially restore the structure in a piecemeal fashion, or (4) totally restore it. A complete restoration would include replacing all deteriorated wooden materials, recessing all electric wiring, installing a new heating system and confessionals, rebuilding the bell towers, and plastering with mud or stucco.

The decision was made to restore the church. In the interest of time work began almost immediately to beat the winter weather and the freezing temperatures that precluded most construction. To retard erosion, the adobe bricks in the parapets were replaced with concrete blocks, and a new balcony floor and stairs were installed. The interior was replastered and painted. On February 3, 1967, the council decided to proceed with cement plaster applied over wire mesh.

The reaction to this decision was immediate. Several architects and other interested parties strongly recommended against plaster, mostly on aesthetic grounds. The reasons they presented, however, were not sufficient to outweigh the economic savings to be derived, and the church was surfaced with cement plaster.

But hard plaster and adobe are not compatible materials. Cement plaster is a fine finish material if applied to a stable base; unfortunately adobe does not provide that base. Because the unfired mud bricks attract moisture, they expand and contract to a considerable degree. But they also permit the passage of water if they are allowed to breathe; that is, if moisture eventually finds its way to the air and evaporates. When adobe is mud plastered, fewer problems exist because the atmosphere sucks much of the moisture from the bricks. When a wall is hard plastered, however, the moisture is trapped behind the cement skin. As the adobes move, the stucco cracks, allowing moisture behind the hard plaster and subsequently behind the cement skin. In time the once-dry bricks become like mud, eventually causing wall failure.

Cracks appeared in the stucco almost immediately. In 1970–1971 a painting contractor tried to patch the cracks with fiberglass tape. Within a year the rear buttresses had a major transverse crack, and the two front buttresses appeared unstable. In 1979 the Santa Fe architectural firm of Johnson-Nestor was requested to prepare a report on the church.[13] The firm offered the following alternatives: (1) refurbish all existing exterior stucco, (2) maintain existing stucco, (3) mud plaster the facade only, or (4) return entirely to mud plaster. By that time some portions of the buttresses included adobe that was the consistency of "brownie dough."[14] The church, in an extremely difficult and sensitive decision, returned to mud plaster.

The story of the mud plastering of the church is a happy one. The return to a form of the past meant that some aspects of modern construction, and perhaps modern life, were not as valuable as an almost archaic method that had been abandoned for economic expediency. Money was short; people were many. The congregation decided it would undertake the work itself over a period of two summers beginning in 1979. The rear buttresses were taken down and completely rebuilt. Some said the church would fall when they were removed; it did not. New adobes were installed where needed, and the tedious job of removing all the stucco and chicken wire was carried out. The work was a fiesta that continued for months, with cooking and eating on the site. Not only was the church building itself being renovated but the congregation as a social institution was also undergoing the same process of renewal. In time the work was completed: a new buttress in the apse, two new buttresses supporting the towers in the front, and a complete new coating of mud plaster over the entire church. In all, twenty thousand adobe bricks were made and installed.

The restoration was an unquestionable success. In late 1981 the reredoses were also undergoing restoration, but at the hands of a professional. As the incumbent pastor of Ranchos de Taos, Father Michael O'Brien, said, "Our church 'is' human. The link and bond between an adobe church and its people are strong and require commitment; we keep the church together and the church keeps us together."[15]

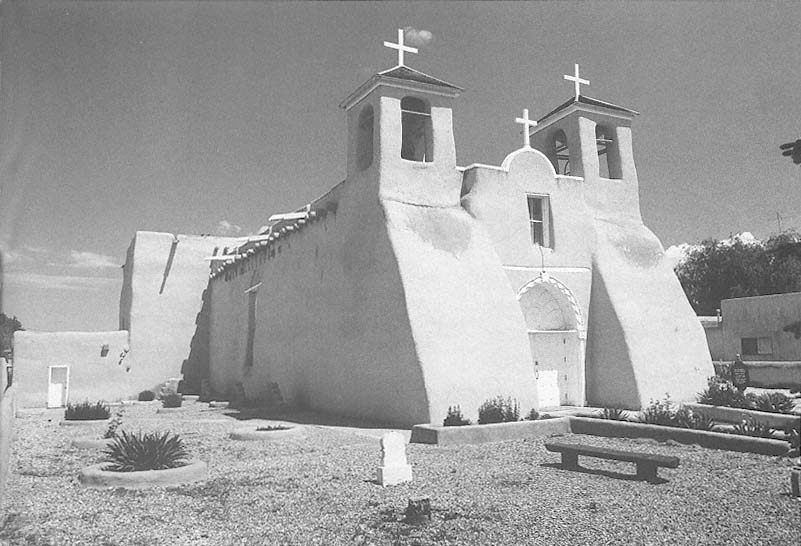

15–8

Ranchos de Taos

The mass, profile, and proportions of the stubby towers provide the church with a powerful, although somewhat

ungainly, repose.

[1986]