Picuris Pueblo:

San Lorenzo

c. 1620; 1706; 1740s; c. 1776; late 1960s; 1986+

Today the pueblo of Picuris remains relatively small and tranquil, still removed from the major settlements of the state. Yet during its history it played the role of political instigator on more than one occasion. Positioned in the mountains north of Santa Fe on the High Road to Taos, the location of the village ensured contact with the Apache and the Comanche as well as with the remainder of the Pueblo tribes that occupied the Rio Grande valley. The earliest contact with Europeans came with Gaspar Castaño de Sosa in 1581.[1] Fray Francisco de Zamora was charged with the establishment of a permanent mission at Picuris, and under his custody at least a rudimentary chapel dedicated to patron San Lorenzo was erected. In 1620 the church was under the charge of Martín de Arvide, and by the later part of the decade the religious enterprise was a going concern, serving several surrounding villages in addition to Picuris itself.

Benavides had mixed respect for Picuris: "Picuries [sic ] pueblo; more than 2,000 baptized Indians, it has its convent and church. They have been the most indomitable and treacherous people of this whole kingdom."[2] His report implied there was a good-sized edifice with convento at Picuris; his observation was confirmed by Agustín de Vetancurt.[3] Around midcentury the pueblo was said to have "a very good church and convento . . . and 564 souls under its administration."[4] The mission was federated with that of Taos and was originally a single district under the jurisdiction of Francisco de Zamora. In the church records Picuris was continually cited for its basic lack of interest or intractability toward conversion. Tupatu of Picuris was one of the principal antagonists in the 1680 rebellion. Under his instigation the resident priest was murdered and the church burned before the party of insurrectionists marched south to join the main attack on Santa Fe.

When Vargas returned to New Mexico twelve years later, the village was deserted, perhaps out of fear of Spanish reprisals. The church lay in ruins. In his usual manner Vargas induced the inhabitants of the village to return, which they did, and probably built a new church or repaired the old one. The governor found the church "very filthy" in 1696, with Indian designs painted on the walls and the door in disrepair. Kubler questioned whether this structure and that repaired in 1706 were the same structure as the church Benavides had mentioned.[5] The village was vacated again in 1704—Forrest attributed this to superstition[6] —and its inhabitants went to live with one of the Apache groups for a two-year period. They returned in 1706, rebuilt the pueblo, and presumably rebuilt the church.

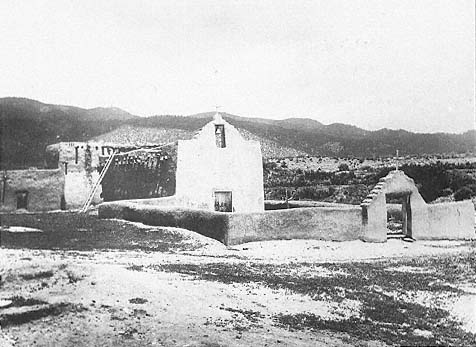

14–1

San Lorenzo

1899

Before the start of the twentieth century San Lorenzo had a typical cross-shaped plan and

a flat facade with a single bell arch.

[Adam C. Vroman, Museum of New Mexico]

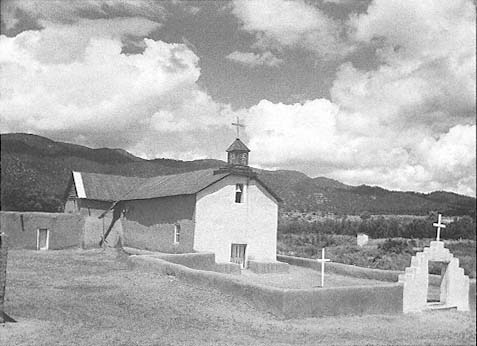

14–2

San Lorenzo

1935

Following a nearly typical pattern, the church—with its metal roof and stubby belfry—

looks more like a schoolhouse than a church.

[T. Harmon Parkhurst, Museum of New Mexico]

During the decade 1740–1750 the mission was again restored. Much of the work was due, by his own admission, to the efforts of Fray Fernando Duque de Estrada, who resided in the pueblo from 1746 to 1747. He claimed to have built the sanctuary "from the foundations up," whitewashed the church, leveled and packed the dirt floor, constructed a belfry, built a crenelated parapet around the entire church, and restored the campo santo as well as providing interior furnishings. He also directed his attention toward remodeling the convento and its kitchen.[7]

Much of this was to no avail. Barely a year later his successor noted that Duque de Estrada had moved the kitchen, oven, doors, and windows to the upper floor, leaving on the first floor "nothing . . . but the ruins of what was before."[8] By 1749 there was "nothing at this mission but disrepair and misery."[9] Tamarón left no words on the church, but by the end of the 1750s Governor Antonio Marín del Valle had discovered the pueblo in ruins. The Comanche completed what nature had begun, conclusively destroying the mission in 1769 in its relatively defenseless position on the outskirts of the pueblo. Fearing another sacrilege, Governor Pedro Fermín de Mendinueta ordered that what remained of the building be leveled to the ground and a new church constructed in a more defensible location. The new church was under construction in 1776 when Domínguez arrived at Picuris to look things over and report.

The story of the new church's construction is of interest because it illustrates the presence of Hispanic building skill even in the building of churches in Indian pueblos. This may have been the principal vehicle for the introduction of the Spanish architectural tradition into that of the Indian, with the civilian builder serving as a sort of technical intermediary between the stylistic ideas of the padres and the common construction competence of the Indians. In any event a civil contract to construct the church was enacted between Fray Sebastián Ángel Fernández of Santa Cruz and Alcalde Salvador García de Noriega. It was to be a complete package, what today would be termed a turnkey project, including "transepts, door, two windows to the east, choir loft, corbels and round beams, plus a three-room dwelling, a sort of token convento."[10] The payment was to be in goods, and the amount of goods that the good friar had at his disposal seemed to wrinkle the eyebrow of Domínguez, who perhaps believed that there should be less commercial dealing and more converting. The renumeration was to be "12 cows, 12 yearling calves, 25 ewes with a stud ram,

14–3

San Lorenzo

circa 1935

The simple spatial configuration of the church is

graced by a handsome reredos and an ornate railing.

[T. Harmon Parkhurst, Museum of New Mexico]

a fine she-mule, 100 fanegas of maize and wheat," and for his sweet tooth "100 pounds of chocolate," enough to keep a child, and one suspects, a padre, content for years.[11] Notwithstanding the seemingly lavish payment, our first commentator, Father José Benito Pereyro, taking inventory in 1808, termed it just ordinary.[12]

Domínguez opened his report by explaining why there was neither church nor convento, that is, the problem of the Comanche raids and how the governor ordered that the defenseless church be torn down. "These raids are so daring that this father I have mentioned [Andrés Claramonte] assures me that he escaped by a miracle in the year '69, for they sacked the convent and destroyed his meager supplies; yet he considered them well spent in exchange for his life and freedom from captivity."[13] Domínguez continued by describing how the new church was in a much better position:

This [the new location] is near one block of, but outside, one plaza of the pueblo, with the intention that the convent shall be in that block. But according to the plan, all is to be defensible as a unit, for the present space between the church and the block where the convent is to be built will be a cloister. The new church is adobe with quite thick walls, single-naved with the outlook and main door due south. It is 24 varas long, 7 wide, and what has been built is 3 varas high.[14]

Even after a century of Christianization efforts, the friar had to fend for himself. The people remained unconvinced.

The pueblo does part of the sowing, cultivation, and harvesting, but for the time being the present missionary bears most of the work. When I remonstrated him, citing the custom among the Indians, he replied: That since they are so lazy, even in their own affairs, they are even more inclined to let what belongs to the father be lost, and so to avoid animosities, gossip, etc., he considers it a pleasure to do it himself, even to the threshing of the wheat with six of his own animals.[15]

To live in the wilderness, the eighteenth-century Spanish missionary in New Mexico needed to be both diplomat and stoic. The census then stood at sixty-four families with 223 persons, down even from the drastically reduced 328 Indians of the Tamarón census of 1760.

The convento was at least sufficiently rebuilt in 1780 to allow habitation. Fray Francisco Martín Bueno underwrote the cost of the altar screen added in 1785–1787. In 1833 Bishop Zubiría, who had a critical eye, related that "it lacks many other things, even a legitimate altar stone, for there is none there

14–4

San Lorenzo, Plan

[Sources: National Park Service Remote Sensing;

and field observations, 1986]

with sepulcher and relics."[16] From this point on life seemed to even out and rest quietly.

"The first building I entered was the church," reported Lieutenant John Bourke in 1881, "where I found the 'governor' of the Pueblo, Nepomuceno, who with others of his tribe was engaged in carpentry work, making a new altar and other much needed repairs."[17] About the church he said nothing more, but Bourke's sketch, like early photos, showed the building to be both simple and severe. The transepts and clerestory were clearly articulated by their additional height, fronted by a simple south facade with small arch enclosing a bell, topped by a cross. A wall of adobe six or seven feet high surrounded the campo santo, which was entered by a gate surmounted by a softened pedimented form. A ladder rested on the west wall, as it often does today. An 1899 photograph by Vroman illustrated this planar facade with its elongated bell opening and simple Territorial Style pediment above the door.

Early in this century the church received a metal pitched roof and a belfry, both of which gave it that distinctive schoolhouse look that many New Mexican churches had to suffer. The surrounding wall was lowered, and by 1935 it was barely three feet high in places—certainly none of the architectural sense of enclosure produced by the high wall remained. The stepped sky altar motif of the gateway was more pronounced, while two adobe bases appeared in a circa 1935 photograph on either side of the door. The south wall of the church was whitewashed and was strikingly distinguished from the earthen remainder.

In the late 1960s the church underwent restoration; the result producing a building of visual simplicity and interest.[18] The pitched roof was removed and the traditional flat roof reintroduced. The south, or principal, facade was extended past the side walls so that it read as a front applied to the church, a literal rendering of the word facade. Two small wings, like the old Santa Clara, flanked each side of the pediment, which was reconstructed to better proportions with a marked stepped profile. Painted white, as was the gateway, the contrast of this brilliant plane against the brown cement plaster that covered the remainder of the building was exceptionally striking on a clear autumn day [Plate 12]. Trapped between the gateway and the plane of the entry is the campo santo with its single cross. The cross on the bare earth is a fitting symbol of missionary efforts in New Mexico; one must have faith to project cultivation into the barren soil.

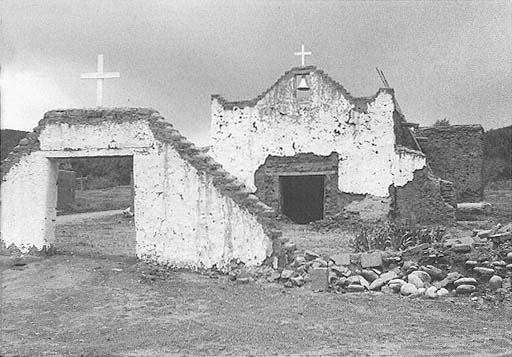

The collapse of a portion of the nave wall in spring of 1986 occasioned a major restoration of San Lorenzo. The reasons were familiar, the root of them being the cement stucco that covered the adobe walls. Even though the concrete "ribbon beams" helped thwart coving at the base of the wall, they could do little to alleviate the problems created by cracks in the stucco and the seepage of water into the earthen blocks of which the wall was made.[19] The work in progress is a major rebuilding, what in the eighteenth century might have been termed "a new church."

14–5

San Lorenzo

The apse end.

[1981]

14–6

San Lorenzo

In 1986, portions of the nave walls had given way and the church as a whole was badly

deteriorated, although it was in the course of rebuilding.

[1986]