Chimayo:

El Santuario

1816; 1920s

L. Bradford Prince, writing in 1915, had only good things to say about the Chimayo valley; truly he found it the Land of Enchantment:

It would be difficult to find a population more entirely cut off from the vices and frivolities of the world, as well as from its newer conveniences and luxuries, than of Chimayo. The people are contented to live almost entirely on the products of their own valley. Money is little needed where requirements for happiness are so few; and the community illustrates the philosophy of content, which proclaims that happiness is not attained by the multiplication of possessions, but by the satisfaction of a few real wants of man, and the absence of desire for anything that is unattained.[1]

The twentieth century has entered the town and valley forcefully, particularly in the postwar period with the impact of television and the automobile, but certain traditional aspects of the place still linger. These include a noted restaurant that draws diners from all around the state, the continuation of the Ortega family's long tradition of Chimayo blankets, the growing of small apples and apricots, and the Santuario de Chimayo, which has attracted pilgrims from an extremely large area for almost two centuries.

With the Reconquest of 1693 came a steady influx of Spanish and Mexican settlers into northern New Mexico. Santa Fe already contained its fill and could provide land for neither shelter nor agriculture. To the south the land was less fertile, much of it already occupied by the sedentary pueblos, and so Diego de Vargas, seeking a solution, looked north. Colonizing San Gabriel had provided a familiarity with the mountain valley lands between Santa Fe and Taos (the zone that runs along what is now known as the High Road to Taos). Vargas's first effort was to relocate the Tano Indians who had been living in the Galisteo basin to the Chimayo valley farther north and east, vacating the lands for the "reinstituted" settlement of Santa Cruz. The Indians had little time to establish thriving farms because hardly a year later increased pressure for land by the Spanish forced them to move once again. The Spanish incessantly spread out, usually moving north into the Chimayo valley, occupying and farming the fertile, protected valleys irrigated more or less automatically by mountain streams.

The land, however, was hardly quiet or free of danger, and the Indians did not always accept their displacement willingly or without a fight. In 1696 there was a minor insurrection, quickly suppressed, which like the revolt of 1680 originated in the northern pueblos. The continual shifting of homelands

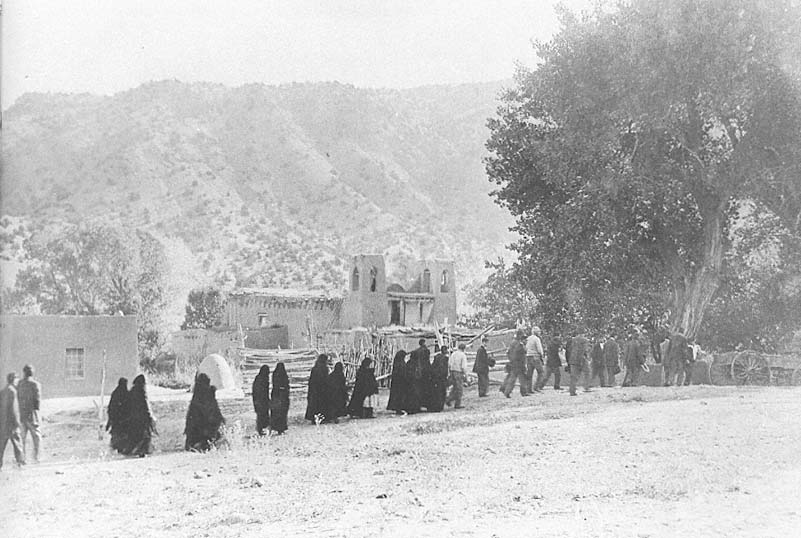

12–1

El Santuario, A Procession

circa 1917

The Santuario in its prior form, with flat roof and without wooden caps to the towers.

[Museum of New Mexico]

may have been an important factor contributing to this flare-up. Following the directives of the crown and the viceroy (the king's agent in the New World), the town of Chimayo, formalized about 1695, was arranged in the form of a fortified plaza (known as the Plaza del Cerro). The walls of the dwellings and animal structures were made contiguous, with only small doors and gates of heavy wooden construction admitting passage. Inside the ring of structures were limited pasture lands for cattle and sheep in the event of siege or attack by the natives. Today the plaza at Chimayo is the best preserved (although much restored) of these arrangements and provides an excellent picture of the town type that also served as the basis for planning at Las Trampas and Ranchos de Taos farther north. The small Oratorio de San Buenaventura remains on the west side of the plaza under the care of the Ortega family.

The families that originally settled the Chimayo valley came from the valley of Mexico and were part of the group that settled Santa Cruz. Among them, as Stephen de Borhegyi reported in an excellent study of the shrine, was one Diego de Veitia.[2] The name has changed within the family over the centuries, and from the original spelling and pronunciation it was modified to de Beyta when he moved to Santa Cruz and became Abeyta at Chimayo.

Against the hardships of winter and the native population but with the blessing of fertile soils and sufficient water, the small settlement managed to thrive and grow. Prince credited Abeyta with particular abundance, the reasons for which he thanked the Lord by building a chapel on his land.[3] On November 15, 1813, Bernardo Abeyta, representing nineteen families, petitioned the Very Reverend Álvarez, who forwarded the request for construction to the vicar general of the diocese, stating that "the miraculous Image of our Lord of Esquípulas has been already honored for three years in the hermita , a small chapel next to Bernardo Abeyta who built it."[4] The petition recorded the first mention of the curious connection between the Santuario of Chimayo and its predecessor in Guatemala.

During the conquest of Central America the Spanish were aided in several instances by allied Indian groups. The Tlascalan Indians, for example, were granted special favors in response to their alliance and possibly served as laborers and model settlers as the Spanish pushed settlements further north (see San Miguel). The Guatemalan chief Esquípulas also saw the futility, one assumes, of fighting against superior arms and supplies and was astute enough to surrender his town to avoid loss of life. In his honor the Spanish named the town Santiago de Esquípulas, which combined the name of the chief with that of the holy military patron Santiago, who had inspired the Christian forces against the Muslims. The town soon became a local trading center, and the consequent accumulation of wealth and resources was expressed in religious images.

One example of this art was an image of Christ made from balsam and orange wood by local woodcarver Quirio Catano. The color of the natural grain of the wood endowed the statue with the facial skin tones of the Indians. The carving soon became famous for its curative power. Among the sufferers who were cured through the intervention of this Christ of Esquípulas was the bishop of Guatemala, Pedro Pardo de Figueroa, the victim of "contagious disease." He began construction of a chapel to house the image, but it was not completed until after his death. His body was interred there, along with the Christ figure, in 1758, and the site became a venerated destination.

Part of the ritual of pilgrimage was the consumption of clay (a practice known as geophagy) pressed into small tablets. This custom had parallels in certain practices of the Pueblo Indians in the American Southwest. Among the Hispanic settlements there was only one recorded instance of the practice: at the Santuario de Chimayo. Here the clay, or tierra bendita (blessed earth), was found in a pit in the chamber to the west of the sanctuary. Prayer, pilgrimage, and ingestion of a small amount of this substance were supposed to cure the afflicted of "pains, rheumatism, sore throat, paralysis and childbirth."[5]

Into the early twentieth century, Prince told us, there was a daily stream of visitors to the shrine:

Every day throughout the year, men, women, and children from all directions, from Colorado on the north to Chihuahua and Sonora on the south, may be seen approaching the shrine, in carriages, in wagons, on horses, on burros, or on foot; but all inspired with full faith in the supernatural remedial power that is here manifested, and high hopes that a good Providence will vouchsafe life and health to the suffering pilgrim.[6]

The pilgrimage continues to this day.

According to legend, the Indian name for Chimayo, Tsimmayo, suggested the site of healing spirits, possibly in the form of warm or sulphurous springs. The valley was first inhabited some time between 1100 and 1400, which coincided with the migration of the Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde peoples. Thus, once again there is a coincidence of Indian and Hispanic cultures, in this case the overlaying of a source of healing with a legend originating in Guatemala, applied to a site traditionally

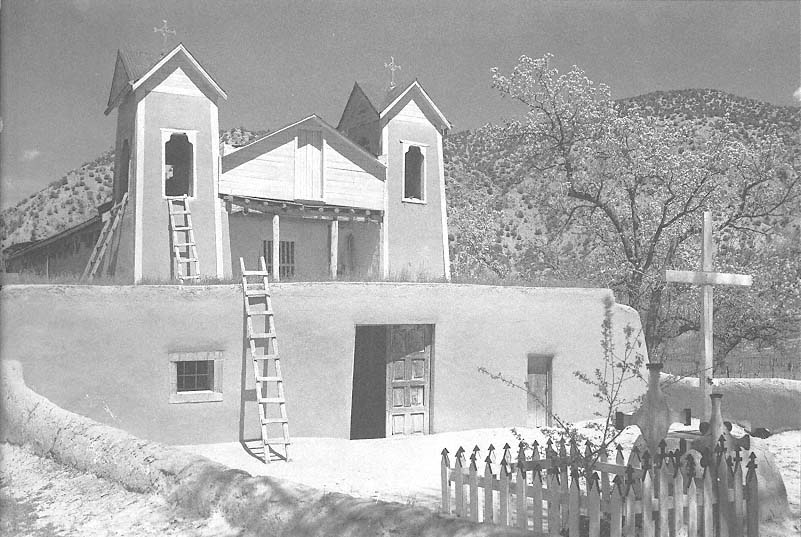

12–2

El Santuario

circa 1935

The addition of the pitched roof closed the nave to clerestory lighting and necessitated a gable on the facade. The building was

trimmed in wood and topped by two roofs.

[T. Harmon Parkhurst, Museum of New Mexico]

regarded by the Indians as ameliorative prior to European contact.

The chapel was originally annexed to the Abeyta farmstead. In a letter Reverend Álvarez wrote that "the most decent and appropriate spot on the said plaza fortified village, or Rancho de Potrero, is called El Santuario de Esquípulas, where they can worship the lord."[7] Thus, the current structure replaced a smaller preexisting chapel that was deemed too meager or too private. The application for a new structure was approved at the bishopric in Durango in a letter dated February 8, 1814. The letter reached the custos, Fray Francisco de Otacio, and in April 1815 he granted permission to the faithful Bernardo Abeyta. Sponsored by Abeyta, the chapel was built with the help of the parish.

Although the chapel was built in 1816, its plan type and form match those of missions dating from centuries earlier. With single nave, tapering apse, and twin towers, the building resembles a smaller version of early seventeenth-century churches such as San Esteban at Acoma or San Agustín at Isleta. Built of adobe and plastered with mud, the chapel is roofed by vigas and latíllas covered by a foot or so of packed earth. Fronting the Santuario is a campo santo with a single cross, once again in the traditional pattern. Unusual, however, is its siting, now overgrown with mature cottonwood trees watered by the adjacent creek. The Santuario sits separately from the houses around it, which, unlike those in the rigid rectangle of the plaza nearby, display no conformity to geometric design. By 1816 the threat of attack had become marginal, and the need for a defensive structure was all but negated for an inland settlement such as Chimayo with sufficient elevation from the plains to the east.

Early photographs show the flat-roofed church with towers unadorned by the wooden finials that cap them today. We can assume that during the 1920s the pitched metal roof was added to the chapel, thereby forcing the addition of the pediment between the two towers. The folded wooden hats on the towers were most likely added at this time, given the consistency of the style. These were added for protection against deterioration of the plaster (noticeable in photos from about 1915), which could have led to erosion of the structural adobe bricks. There seems to be some affinity between this remodeling and that of San Augustín at Isleta dating from 1923, where elaborate wooden turrets, pediment, and balcony were added to the solid and stolid adobe base. One enters the Santuario through a zaguán formed by two uncharacteristic storage rooms and an exterior balcony. Early

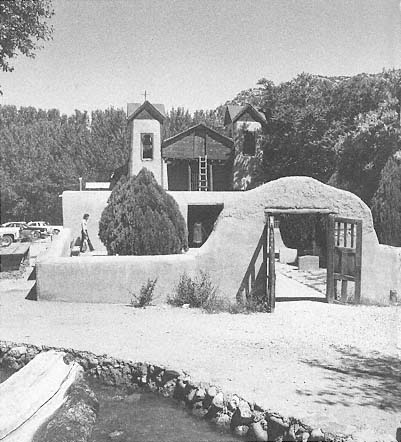

12–3

El Santuario

The entrance and courtyard seen from the creek.

[1986]

12–4

El Santuario, Plan

[Sources: Kubler, The Religious

Architecture , 1940, based on HABS;

and measurements by Susan Lopez,

1987]

lists of goods stored there suggest that sales of commodities donated to the Santuario were used to maintain and administer the site.[8]

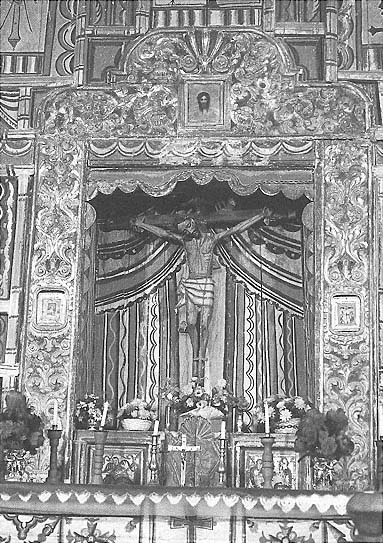

As an act of humility, praise, and faith, the interior of the chapel was highly ornamented—to a degree unacceptable to the Reverend Agustín Fernández de San Vicente. In a letter dated August 29, 1826, he instructed the resident priest of Santa Cruz, who had jurisdiction over the Santuario, to remove all the saints' images painted on animal hides or rough boards.[9] De Borhegyi credited the reredos to José Aragón and the east wall to Miguel Aragón of nearby Cordova, where even today a wonderful tradition of santos wood carvings thrives.[10] The principal reredos are attributed to Molleno, called "the Chile painter."

Today the lavishness of the paintings rivets one's attention forward from the moment of entry into the nave [Plate 7]. The pitched roof blocks the clerestory, a common malady in church remodelings, and the incandescent floodlights that illuminate the reredos only suggest the true power of the directed clerestory lighting once present in the chapel. Nonetheless, one is moved by the sanctity of this small edifice and of the adjacent rooms covered with votive offerings with gratitude for miracles rendered to the afflicted faithful.

Some time between 1850 and 1860, apparently prompted by jealousy of the trade generated by the Santuario, a neighbor built a second chapel, this one dedicated to the Santo Niño de Atocha. Its popularity drained the revenue of the Santuario's owners, who ultimately acquired a Santo Niño of their own—although they selected by mistake an image of the Holy Child of Prague. The statue currently rests in the room with the pit of sacred earth.[11]

Possession of the chapel passed to Abeyta's daughter, who maintained it, as he did, with access to all. She was troubled by an overzealous clergy, who perhaps believed that the possession of the chapel should rest with the archdiocese in Santa Fe. Apparently various threats failed to gain their intended object, and the daughter steadfastly held on to her inheritance. In time the conflict became known to church authorities and the matter was settled.[12] In 1929 title was transferred to the archdiocese of Santa Fe through the generosity of an anonymous donor, "a Roman Catholic graduate of Yale."[13]

Because the chapel and site have a collective history that predates the arrival of the Spanish, there are a series of legends associated with the place. De Borhegyi explained that most of these stories deal with apparition and disappearance in groups of three and with the taking and return of some

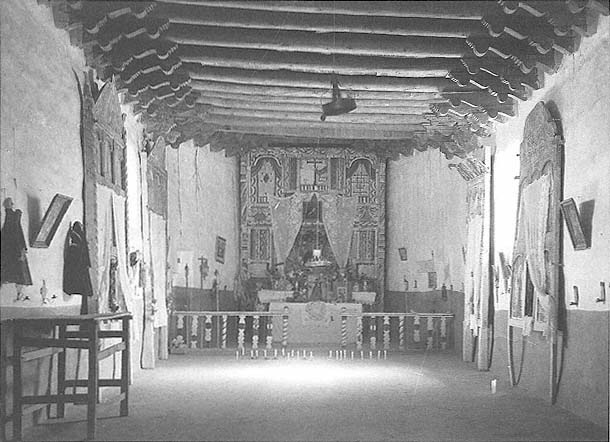

12–5

El Santuario

circa 1915

The interior before the addition of the pews. The subsidiary reredoses flank the nave.

[Museum of New Mexico]

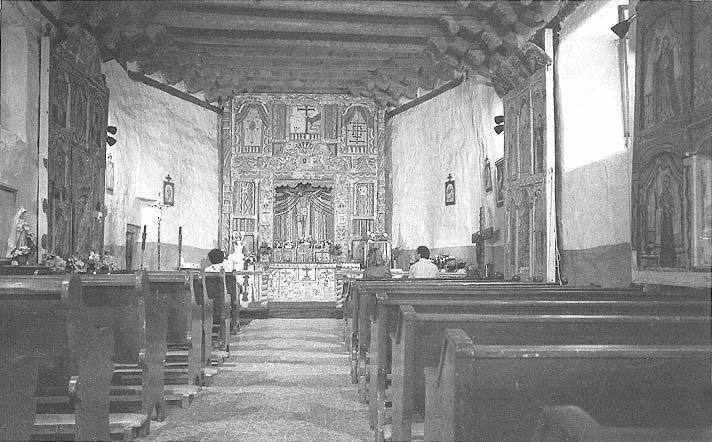

12–6

El Santuario

Artificial illumination today replaces the original clerestory and window lighting in the nave.

[1981]

12–7

El Santuario

Detail of the vigas, carved wooden corbels, and milled ceiling boards.

[1982]

object.[14] For example, Bernardo Abeyta saw a bright light one day and found the crucifix of Our Lord of Esquípulas. Abeyta placed it in the main altar of his chapel, but the next morning, to his surprise, found that it was missing. This happened three times. Realizing that this must be a sign, he later constructed the chapel over the hole where the crucifix had been found. A similar story was told of a Picuris shepherd who found an image of Saint Istipula and put it under his pillow.

At Chimayo, the traditional home of the Tewa immigrants to the Hopi, there is preserved in a room of the church a hole in the ground of which clay has in the Indian opinion potent medicinal value, "good for pains in the body, and for being sad," said my Isletan informant. Twice he had visited the "santuario" or Shamno, as it is called from the man of Picuris (Shamnoag) who first found the saint. He was out herding sheep. With his crook he was tapping some rocks and there by a big rock he found the saint, Saint Istipula. He was made of clay. The old herder took the image and placed it overnight by his pillow. In the morning the saint had disappeared; he had gone back to his rock where the herder sought him and found him. But from there, too, the morning after, the saint disappeared. The herder returned to the rock and there was the saint. So the herder thought there was no use in carrying the saint away and on that spot he built a shade for him. Later in some way Mexicans got possession of this place.[15]

Among the best-known images in the Santuario is a rather small statue of Santiago. This figure has traditionally been decorated with crafted flowers and candles and even pictures of the pilgrims offering thanks for the healing properties of this representative of the saint. In earlier times, E. Boyd noted, the figure received tiny boots, sombreros, and even bridles in thanks for children cured.[16] The figure has been painted many times during its history, but it was restored in 1955 by Alan Vedder of the Spanish Colonial Department of the Museum of New Mexico.

Veneration for the Santuario of Chimayo continues to this day. Marc Simmons reported that in response to the extremely high losses suffered by New Mexicans in the early part of the Pacific War, including the infamous Bataan death march, "some of the survivors, keeping a vow made during that harrowing time, later undertook a pilgrimage on foot to the rustic adobe Santuario de Chimayo."[17] Sanctity lies embedded in this place.

12–8

El Santuario

Detail of the restored reredos.

[1981]