Colonization

Only in the 1580s was interest in the colonization of New Mexico revived as profitable silver mining in northern Mexico suggested that long-term efforts, rather than quick gains, in New Mexico might prove financially rewarding. In addition was the prospect of thousands of Indians waiting for conversion: people whose existence had been confirmed. As a result, a royal decree of 1583 delegated the viceroy of New Spain to organize the settlement of New Mexico. Considered a politically attractive and potentially lucrative post, the governorship of the new province was actively solicited. The appointment was finally awarded to Don Juan de Oñate of Zacatecas, who provided most of the financial support for the expedition himself and spent three years assembling the necessary supplies, settlers, stock, and permissions.

Even though the lands of the New World were the property of the king, in matters of their administration he was advised by the Council of the Indies, a group composed of humanists, politicians, and religious figures. Articles, later formalized as the Royal Ordinances on Colonization and commonly referred to as the Laws of the Indies, specified in great detail who could and should found colonies, where towns should be sited, where certain buildings should be placed, and so forth. The native peoples were seen as a resource to be protected and educated until ready to enter European culture. In principle the articles, for their time, treated the natives remarkably fairly, proscribing their exploitation or genocide. Article 5, for example, exhorted colonists to "look carefully at the places and ports where it might be possible to build Spanish settlements without damage to the Indian population."[13] Although the articles were imbued with the humanism of the times, they were overly optimistic in their conception of human nature, and their actual implementation often fell short of the spirit that created them.

Royal approval for Oñate's expedition was finally issued in 1598, and he set out accompanied by five Franciscans who had been granted the religious jurisdiction of the new province. New Mexico had been deemed a nullius , a land without the benefit of a bishop or regular clergy, and had been assigned to Franciscan jurisdiction. Oñate more than met the requirements of Article 89 of the revised Laws of the Indies, which governed the requisite numbers of settlers, livestock, and clergy to accompany an expedition. Burdened with thousands of head of cattle and sheep; 400 men, of whom 130 had families;[14] 200 soldiers; and 5 priests in eighty-three wagons, the expedition moved slowly.

Military protection was a necessity not only for the journey but also for the founding of missions. Two to six soldiers were assigned to maintain the religious enterprise, although the friars were often more fearful of the poor example the soldiers might set than of danger from the Indians. Centuries later the problem remained unchanged. Fray Romualdo Vartagena, guardian of the College of Santa Cruz de Querétaro, wrote in a manuscript dated 1772:

What gives these missions their permanency is the aid which they receive from the Catholic arms. Without them pueblos are frequently abandoned, and ministers are murdered by the barbarians. It is seen everyday that in missions where there are not soldiers there is no success, for the Indians, being children of fear, are more strongly appealed to by the glistening of the sword than by the voice of five missionaries. Soldiers are necessary to defend the Indians from the enemy, and to keep an eye on the mission Indians, now to encourage, now to carry news to the nearest presidio [fort] in case of trouble.[15]

That both the presidios and missions were financed from the same source, the War Fund, suggests the basically hostile nature of colonization.

Oñate's expedition followed the most logical highway, the Rio Grande, and entered New Mexico through El Paso del Norte (The Pass to the North, or El Paso, now part of Texas). This route was more direct than the one taken by earlier expeditions;

without the benefit of real roads, travel followed the river valleys, which provided the benefit of a defined path and an assured source of water. From central Mexico northward there were two primary routes separated by hundreds of miles of desert: the Rio Grande drainage in New Mexico and the Gila River drainage in Arizona. Mission systems were founded along both rivers, but contact between these geographic areas was negligible until the arrival of the railroad in the nineteenth century. Like the lands between the two river systems, the Indians who dwelled in them were groups apart.[16] Acoma occupied a fringe of the Rio Grande missions, and pueblos like Zuñi and Hopi were difficult to administer because they lay too far from either jurisdiction. Zuñi, as a result, suffered its lapses of missionary presence, and Hopi was never convincingly brought within the Catholic circle.

As the Oñate group traveled north, it nominally pacified the Pueblo Indians with whom it came in contact and extorted an oath of allegiance to guarantee future obedience. The natives were to acknowledge that there was one God and one king, the former residing in heaven, the latter in Spain. After nearly half a year, the expedition reached what became its destination: the town of Ohke, rechristened San Juan de los Caballeros by the settlers, near the present-day town of Española. Because winter was rapidly approaching and insufficient time remained to build shelter, the Spanish commandeered a segment of the pueblo in which to live. As time and weather permitted, they set about constructing their own dwellings and a crude chapel to serve the entire colony and undertook rudimentary farming. The first church was dedicated in September 1598, although the structure was still incomplete. The Indian residents of San Juan were apparently calm—probably more out of fear than generosity—in tolerating the Spanish incursion.

In late fall 1598, Oñate dispatched a survey expedition of soldiers to explore certain lands to the west, including Acoma. The Spanish were brutally attacked and decimated by the Acoma warriors. In retaliation, Oñate ordered a party headed by Vicente de Zaldívar to avenge these deaths. Zaldívar's men fought their way to the top of the mesa and eventually took the battle, but the bloodshed did not end there. Oñate decreed that all "men over 25 were to have one foot cut off and spend 20 years in personal servitude; young men between the ages of twelve and 25, 20 years of personal servitude; women over twelve, 20 years of personal servitude; 60 young girls to be sent to Mexico City for service in convents, never to see their homeland again."[17] Today this chronicle, although probably exaggerated, still seems particularly severe despite the fact that its perpetrators were desperate to establish a precedent for obedience and control of the native peoples.

Having secured military control of the territory, the Spanish turned to its administration. The encomienda was a central aspect of settlement policy in both Mexico and New Mexico and served as the basis for religious and economic administration when the northern province was colonized.[18] Under the encomienda system, all land was ultimately held by the king, but tracts could be granted in his name to individuals by the royal representative. Together with the land, settlers, friars, or churches could also be assigned as "trustees" (encomenderos ) for one or more Indians. A trustee was "strictly charged by the sovereign, as a condition of his grant, to provide for the protection, the conversion, and the civilization of the natives. In return, he was empowered to exploit their labor, sharing profits with the king."[19] The Spanish thereby encouraged the education of native peoples to the ways of European religion, civilization, and technology but in turn taxed them for the privilege. The encomienda served a military purpose as well. Because the governor was responsible for the protection of the colony, it was to the common good to create a civil militia to augment the scant complement of regular troops. No funds were earmarked for this purpose, but the encomendero could be paid in tribute goods by the Indians he protected. The law specified that goods, not labor, be used as currency, but this was often not the case. In New Mexico "heads of Indian households were required to pay a yearly tribute in corn and blankets to the Spaniards. That put affairs on an orderly basis, since the Pueblo peoples now knew exactly what their obligation was, but it made the burden no more palatable."[20]

The Franciscan, as religious leader, oversaw the spiritual welfare of his charges through the catechism, baptism, and mass. Policy dictated that after conversion individuals could not depart from the church or, once settled in a village, had to remain in residence until the period of encomienda was terminated or the mission was secularized. In some parts of the Spanish New World the encomienda could be hereditary through at least two generations.[21] In others ten years was assumed to be sufficient for the completion of the missionary's work and elevation of the native. But oftentimes ten years was not "sufficient," and the terms were usually extended. His charge seemed not to learn as fast as he should, a colonist might report—not surpris-

1–6

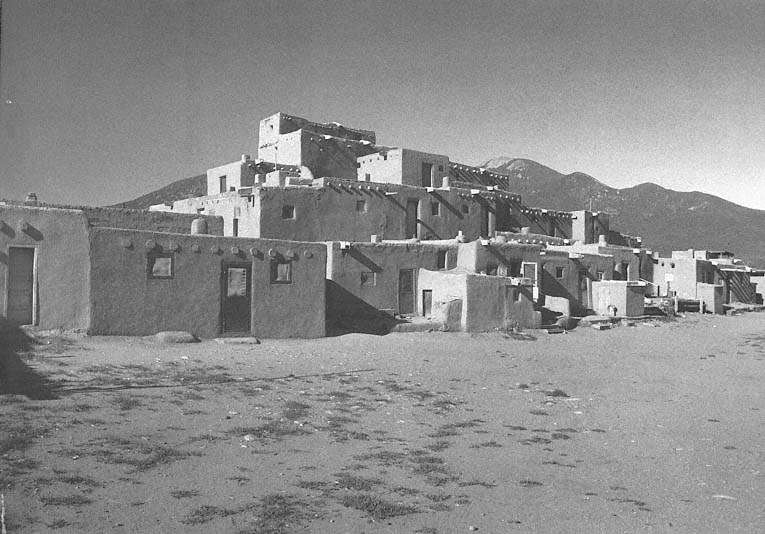

Taos Pueblo

The northern residential block.

[1986]

ing given that Hispanic settlers often exploited the Pueblo peoples mercilessly and treated them as little more than slaves. The imposition of unreasonable burdens left the natives little time to work their own fields, and when the yield was meager, there was hardly enough for the taxes, much less to live on. Attempts to repeal the system in 1542 provoked such a strong reaction by the colonists that modifications were enforced only minimally.

Friction intensified as differences among the various Spanish factions and Governor Oñate solidified. Soldiers and colonists alike were dissatisfied by the limits of Indian productivity and the stringent conditions under which Spanish settlers were forced to live:

They accused the governor of all kinds of crimes and malfeasance. They charged cruelty in sacking Pueblo villages without reason; that he had prevented the raising of corn necessary for the garrison and people and thereby brought on a famine and caused the people to subsist on wild seeds; and insisted that the colony could not possibly succeed unless Oñate was removed. On his part, the governor wrote to the viceroy and the king, charging the friars with various delinquencies and general inefficiency.[22]

To bolster his sagging prestige, Oñate set out in 1604 on an expedition lasting six months; his goal, to find precious metals. In his absence, Oñate's enemies in Mexico increased their advantage. News of the punishment he had meted out, reports of desertion, and the general condition of the colony reflected unfavorably on Oñate in spite of his military accomplishments. His efforts to secure riches for Spain were fruitless. He was ultimately suspended from office in 1607 and subsequently stood trial for indiscretions committed during his tenure.[23]