Our Lady of Lourdes

1890

Two noticeable bumps interrupt the view over San Juan pueblo: the church of San Juan Bautista and the chapel of Our Lady of Lourdes. In contrast to the mostly single-story texture of the pueblo, the chapel and church stand more than two stories high. Built of stone and brick, rather than of native adobe, their Neo-Gothic style contrasts distinctly with the prismatic earthen masses of the low-lying native dwellings. There appears to be no existing common ground between these buildings of two cultures, and the inevitable conclusion is that it is the Christian structures that remain foreign to the site.

As early as 1915—just two years after the construction of the present church—L. Bradford Prince lamented the passing of the earlier adobe sanctuary it replaced, although he added that "no one can fail to revere the devotion which has thus laid its gifts upon the altar, and has made this little Indian pueblo a center of ecclesiastical artistic beauty."[1] His reference was to the generosity of Father Camille Seux, who tended San Juan for more than half a century and was responsible for the building of the church. And while the aesthetic merits and appropriateness of the structure's style might be questioned, they serve as excellent examples of Catholic building at the turn of the twentieth century—illustrating the overlay of alien styles on the traditional foundation of Hispanic-Native architecture.

San Juan Pueblo lies some twenty-eight miles north of Santa Fe on the eastern bank of the Rio Grande. Situated between two forks of the river system—near the confluence of the Rio Grande and the Chama River—the pueblo's rich alluvial plains have provided excellent and continued yields. The distant mountains, considered sacred by the people, provide a dramatic backdrop for the village. San Juan is currently the largest of the Tewa pueblos and for centuries has served as a commercial and religious center, its importance having been diminished only with the impact of automobile transportation.[2]

A branch of the Coronado expedition reached the pueblo of Ohke, or Yunque (Yunqe in Tewa), in 1541, but news of the expedition's summary manner of dealing with other pueblos had preceded its arrival, causing the people to flee to four fortified villages nearby.[3] A half century later Oñate determined that the pueblo would be an excellent center of operations and colonization, and he settled in for the winter. The inhabitants are said to have willingly allowed the Spanish to occupy their village, although, as Ortiz commented, the pueblo's side of the story has not been passed down to us. In return for the gracious manner in which they acted, to Oñate's name "San Juan Bautista" (after Saint John

10–1

San Juan Pueblo

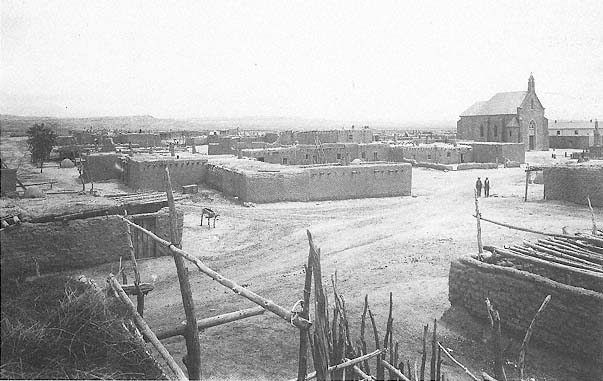

Above the flat plane of the pueblo roofs rises the Gothic form of the chapel of Our Lady of Lourdes.

[Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives]

10–2

San Juan Pueblo

circa 1905

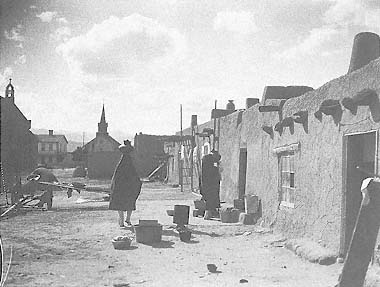

The steeple of the renovated old church punctuates the horizontal

pueblo landscape.

[Edward S. Curtis, Museum of New Mexico]

10–3

San Juan Pueblo

Aerial view of the pueblo showing the church of San Juan Bautista in

the center and the chapel of Our Lady of Lourdes to its left across the

road.

[National Park Service Remote Sensing, 1979]

the Baptist) was appended "de los Caballeros" ("of the gentlemen") by his captain, Gaspar Pérez de Villagra. This anecdote was probably a nineteenth-century fabrication.[4] The qualifying phrase more likely referred to the Knights of Malta, whose patron saint was John the Baptist.[5]

Some decades later Benavides provided his own creation myth: the pueblo converted to Christianity because a miraculous rain alleviated the impact of a serious drought. The inhabitants called on the blessed father to intervene on their behalf: "It was remarkable, for, while the sky was as clear as a diamond, exactly 24 hours after the outcry had gone up, it rained throughout the land so abundantly that the crops recovered in good condition."[6] In the following years pragmatic irrigation, according to Benavides the work of Fray Andrés Bautista, replaced divine intervention and allowed the community to prosper.

Habitation was one aspect of living; relations with God were another. Soon after the arrival of the complete party on August 18, 1598, work commenced. On September 8 the chapel was dedicated, although its fabric remained unfinished. The ceremonies, including sports of both Spanish and Indian varieties, continued for an entire week.[7] With the colony established, the religious enterprise began: Fray Cristóbal de Salazar, with two lay brothers, assumed the jurisdiction of the Tewa pueblos that included San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, and San Juan.[8] During 1599 or 1600 the Spanish established San Gabriel within the pueblo precinct on the opposite bank of the river, a colony that subsisted but did not prosper. Finally, in 1610 the capitol was reestablished in Santa Fe. Although records do not provide a description of the early church, it is believed that the San Juan enterprise included a church, a convento, and the "necessary (auxiliary) facilities for missionary work."[9]

Relations between the pueblo and the Spanish were hardly amiable. As was characteristic of so many New Mexican pueblo stories, the first mutual antagonisms were fanned by the Spanish persecution of native religions and exploitation of Indian labor and resources. A 1664 report, which France Scholes believed to be a supplement to the Relación of Fray Jerónimo de Zárate Salmerón, stated that San Juan at this time was treated as a visita of Santa Clara.[10] In a document concerning the mission program needs for the years 1663 – 1666, however, San Juan was listed as under the jurisdiction of San Ildefonso: "In the convento of San Ildefonso there serves and will serve one friar-priest, who will administer pueblo and six estancias, and because of the lack of

10–4

San Juan Bautista

October 1881

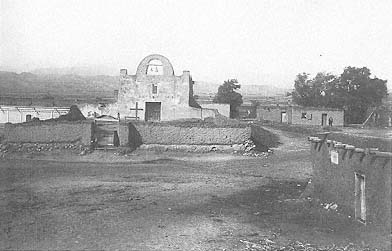

The old church with its distinctive bell arch.

[William H. Rau, Museum of New Mexico]

10–5

San Juan Bautista

circa 1912

Viewed laterally, the historical church is barely visible under its pitched

roof disguise.

[Carlos Vierra, Museum of New Mexico]

friars he visits the convento of Santa Clara of the Tewas, and that of San Juan of the same nation, distinct and separate pueblos; and at least three friars are needed, two priests, and one lay brother."[11]

In 1675, forty-seven Indians were brought to trial in Santa Fe for witchcraft or more likely for the practice of the native religion. Efforts to intercede on their behalf by a medicine man named Popé were unsuccessful. This incident is often cited as contributing to the Pueblo Revolt, in which Popé played a major role.

At the time of the Spanish resettlement in 1693, little or nothing remained of the prerebellion church. In 1706 a new church was under construction.[12] Domínguez credited Fray Juan José Pérez de Mirabal with the "construction" of the church, although this could have meant substantial repairs, not a completely new building.[13] This eighteenth-century structure probably followed the normal pattern of a nave and raised sanctuary and possibly possessed transepts and transverse clerestory.

Bishop Tamarón included San Juan on his 1760 tour of inspection but had more to say about the surrounding countryside than the church building itself. The Indian population stood at fifty families with 316 persons.[14] The 1750 census report of Custodian Andrés Varo, however, had listed the number of Indians as 500.[15] In 1776 Domínguez included San Juan on his survey of the Franciscan project in New Mexico and was little impressed by what he saw. "Poor," "hideous," and "ugly" were the adjectives he used to describe San Juan.

The nave was more than four times as long as it was wide, was about square in section, and gave the appearance of a "gallery," or corridor.[16] The convento was a bit rude, enclosing a courtyard south of the church.[17] There was a choir loft but no access to it within the church; indeed, it could be reached only "from the flat roof of the convent."[18] Over the entry was a single adobe arch supporting two bells without clappers, which people rung by striking them with stones! The floor was bare: "The only dais and carpet are the earth floor."[19] The picture was not a happy one, although Domínguez, perhaps with a sigh of relief, noted that because of the richness of the soils, the land was "sufficient to maintain the friar."[20]

Paintings on buffalo hide, the type that so upset Bourke a century later, included one image of San José and one of San Juan Bautista. Two adobe tables nearby, however, Domínguez termed "hideous."

In 1776 the population stood at sixty-one families with 201 people,[21] a figure that, if accurate, recorded the village's continuing decline. An attack of small-

10–6

San Juan Bautista

circa 1912

The facade was surfaced with plaster carefully scored to resemble cut stone;

with its steeple and architectural trim, the church created the aura of a proper

Anglo church.

[Museum of New Mexico]

10–7

San Juan Bautista

circa 1903

The interior of the old church.

[George H. Pepper, Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation]

pox in 1781 reduced the remaining population by one-third. The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were relatively uneventful at San Juan, with religious and domestic life maintaining a sleepy pace. The relations between the Spanish and the pueblo communities appear to have been less strained than in earlier times, and the secularization of the missions in the first decades of the nineteenth century went almost unnoticed.

Reports dating from 1818 and 1826 described the church as in good repair, with a "renovated baptistry, a new pulpit and confessional, and the cemetery with a deadhouse, depósito de difuntos , for corpses until burial."[22] The 1846 U.S. Army reconnaissance party, of which Lieutenant W. H. Emory was a part, bypassed the Rio Grande pueblos on its way to Santa Fe and California as the territory quietly joined the dominions of the United States.

Of far greater impact on the church institution was the establishment of the new diocese in Santa Fe in 1853. With the installation of Jean-Baptiste Lamy as bishop, the traditional simple mud church structures underwent considerable modification. Lamy brought a new view to New Mexico: the church should raise the educational and aesthetic standards of the parishes. To achieve the second, existing structures were substantially renovated, at times to the point of unrecognizability.

A number of Lamy's priests came from France, like the bishop himself. They seemed intent on exchanging the look of the "primitive" church for that of a "contemporary" (i.e., "polite") institution. The parish church in Santa Fe became the new cathedral, a considerable stone structure in a Romanesque style. Isleta, under Father Etienne Parisis, assumed a Neo-Gothic guise that was curious at best and bizarre at worst, a wooden Gothic crown on an adobe base. San Juan underwent a similar transformation.

The architectural developments of these years, as several authors have noted, must be seen as congruent with the generosity of Fray Camille Seux. Seux, known in a more familiar Spanish form as Padre Camilo, was born in Lyons, France, in 1838 and issued from a family of means. He arrived in the United States in 1865 and served at Taos, Santa Fe, Pecos, and Albuquerque before being assigned to San Juan in 1868.[23] San Juan changed under his hand; during his tenure at the pueblo he had built and paid for a church, a chapel, a statue, and a rectory.

Up to that time the historic form of the church—the "corridor" church of Domínguez's report—had been preserved. In 1881 Bourke found the church

10–8

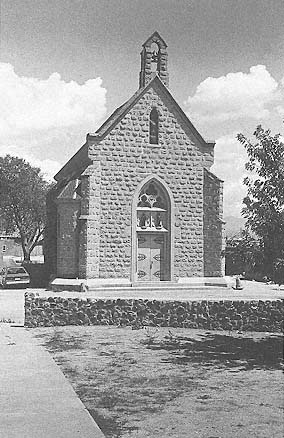

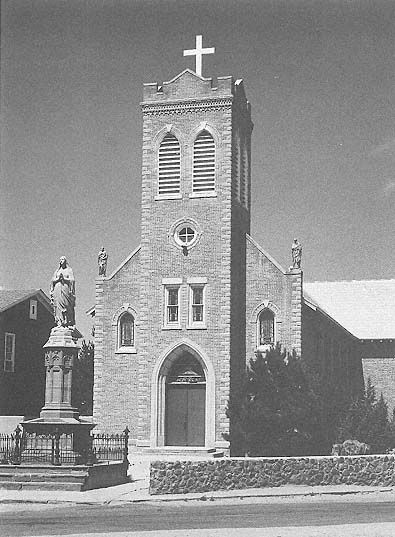

Lourdes Chapel

The rusticated Romanesque stone facade more closely

recalls memories of Europe than the mud buildings of

the adjacent pueblo—a typical practice at the close of

the nineteenth century.

[1981]

10–9

Lourdes Chapel, Plan

[Source: Measured plan by Pat

McMurray and Bob Wicks, 1967;

John Gaw Meem Collection,

University of New Mexico]

to be a "much better structure than at Santa Clara" and remarked that the rear wall of the structure had been washed out by heavy rains the previous summer but that the church had "to all appearances, been restored quite recently, whitewashed and provided with a new altar-piece."[24] First, the existing church was inundated by a Gothic tide. Perhaps closest in appearance to Santa Fe's Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe in a similar state of remodeling, its exterior walls were not covered in wood but in a hard plaster scored to resemble masonry.[25] A single bell tower rested on the facade—in all a successful effort at dressing up an adobe structure to look like a polite masonry edifice.

Father Camilo did not stop here. When a statue of the Virgin, a full-size copy of the one at Lourdes, attracted a flock of pious visitors, he built a chapel to accommodate them. The chapel of Our Lady of Lourdes, built in 1890, was seen by certain contemporaries as a landmark in northern New Mexico, what Prince termed "an architectural jewel set down on the edge of a desert."[26] The single-nave chapel, constructed of red stone with characteristic angular apse and buttresses, was a decent essay in the style, although foreign to the local architectural tradition. Padre Camilo was buried within the chapel in 1922.

During the early part of the twentieth century the church of San Juan Bautista no doubt suffered the ravages of time and the elements. The new pitched roof helped retard water leakage, but the walls beneath it were still adobe and were therefore prone to the extensive expansion and contraction that cause cracking. The hard plaster covering created additional problems by trapping water behind its surface and preventing evaporation. Padre Camilo also saw a new church as his ultimate gift to San Juan Pueblo and the surrounding peoples. The old building fell; the new one rose on the same site.

This new church, consecrated in 1913, once again took the Neo-Gothic style popular at the time, although this was a version of the Gothic quite foreign to France. Built of brick, its design was not particularly distinguished, but with the Lourdes chapel across the street, the church created a suitable backdrop for the statue of the Virgin.

That these two structures abut the traditional field of the pueblo may cause some consternation to the visitor. They are without question imports, sharing neither the soil nor the profile of the traditional buildings. Even Forrest was troubled by it. In 1929 he wrote:

While it [the new church] is a fine, substantial building and would be a credit to any New England town or some other eastern village, the style of architecture is very incongruous out there in the sun-baked desert, surrounded by adobe Indian houses centuries old. It is so strangely out-of-keeping with its surroundings in a land where everything is Spanish that it strikes a harsh, discordant note, and leaves an unpleasant thought of what would otherwise be an ideal visit to old San Juan.[27]

The contemporary critic with less of a romantic streak might find curiosity instead of harsh discord. The distance between the look of vernacular building and that of the church and chapel lucidly depicts the relationship between the architectural and ecclesiastical views of the modern clergy and the tastes of the people. The eighty years that have elapsed since the construction of the two sanctuaries have done little to soften the basic disparity, except by adding the ruddy dust that inevitably coats all buildings in the area. The lesson seems obvious: architecture is a statement of the values behind its construction. The congruence and disparities between two value systems remain clear, even decades later.

10–10

San Juan Bautista

The new church: brick, Neo-Gothic, and a stranger to the earthen structures

of the pueblo.

[1984]

10–11

San Juan Bautista

The smooth plastered surfaces of the nave contrast

with the textured brick exterior.

[1990]

10–12

San Juan Bautista, Plan

[Sources: Measurements by Susan Lopez and Thomas Cordova, 1986; and

Dorothée Imbert and Mare Treib, 1990]