Santa Clara Pueblo:

Santa Clara

1626–1629; c. 1758; 1905 (collapse); c. 1914; late 1960s

Santa Clara is a small Tewa pueblo on the western bank of the Rio Grande not far from Española.[1] Today, although difficult to discern, the formal layout of the pueblo is organized on a loosely defined double-plaza plan. To the north of the pueblo, and quite distinct from it, is the diminutive church of Santa Clara. The structure that stands today exhibits few of the qualities of the older building that collapsed early in this century and certainly none of its cautious grandeur.

Evangelization earnestly began in 1598, the first mission at Santa Clara being established by Fray Alonso de Benavides somewhere between 1626 and 1629. A church was built at this time, although its dimensions and form are not known. A 1664 report stated that "the pueblo of Santa Clara has a very good church, whatever is necessary for public worship, a choir and organ, a fair convento , and a visita in the pueblo of San Juan. . . . It has 993 souls under its administration."[2] If we judge by the amount of increased effort needed to rebuild the ruined church after the Reconquest, its dimensions could not have been impressive. Having no resident friar, Santa Clara witnessed no martyrdom at the hands of the Indians during the revolt, although Spaniards in the vicinity were killed. The mission thereafter remained a visita of San Ildefonso, continuing its religious program when Bishop Tamarón visited the province in 1760. He noted that a missionary resided at the village and that the Indian population of 157 persons almost equaled that of the "citizens," who totaled 277 souls.[3] Domínguez surpassed his usual thoroughness by offering the complete story of the then-extant church.

Because the old church had fallen down, beginning in the year 1758 Father Fray Mariano Rodríguez de la Torre started to build the present one and finished it. . . . Although the Indians and settlers of the mission assisted in this project, no levy was made for the purpose, since most of it was at the father's expense, as is shown by the fact that he supplied twenty yoke of oxen to cart the timbers and he fed the laborers gratis.

When the roof of the nave was finished, the Indians and the settlers left the rest up to the father alone and to his industry. Therefore, what was necessary to roof the transept and sanctuary was taken from alms, and with this he roofed it. The carpenters, in addition to being well paid, ate, drank, and lived in the convent at the father's expense for a period of two months in the winter, when the days are short in this region. And since these workmen are very gluttonous and spoiled (in this land, when there is work to be done in the convents, the workers want a thousand delicacies, and in their homes they eat filth; the gravy

9–1

Santa Clara

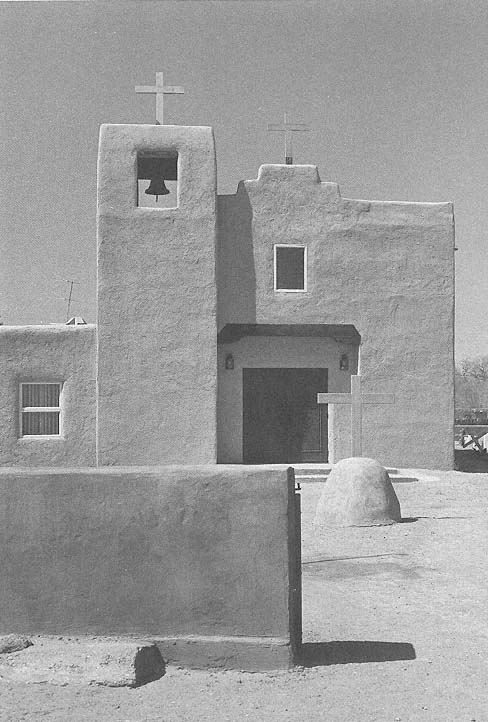

The single tower of the smaller and simplified church was added between 1962 and 1978.

[1981]

cost the father more than the meat (as the saying goes). That is to say, they ate and were paid more than they worked.[4]

While the church was under construction, mass was said in a small chapel or other convenient place. The former chapel found a new use on completion of the new church: "And the reward which has been given to the said shrine for its holy service is that it serves as a stable for dumb beasts that gather in it of their own accord."[5] The new church, Domínguez continued, was built of adobe with thick walls and a main door facing the east. But its proportions were more exaggerated than the common church; in fact, Santa Clara at the time exceeded all other missions in narrowness. The reason, he explained, was that large vigas were more difficult to transport down the rough terrain of the canyons of the west side of the river than from the mountains to the east.

The resulting nave reminded him of a cannon, so long (more than one hundred fifteen feet) and narrow (merely fourteen feet wide) was the nave. There was no choir loft—the good Franciscan even expended a mild joke on that fact. There were transepts, each with a window at the end, and two additional windows on the south side to provide continued light for the nave. The roof contained an unusually high number of vigas, forty-seven he counted; they were of limited diameter and were installed at short intervals to achieve the strength necessary to support the heavy earthen roof. The floor was of earth in the nave, the baptistry, and, naturally, the cemetery.

Over the entry was a small arch with a bell. "There is a sacristy joining the church on the south as did the convento built by Fray Mariano in the form of a square cloister."[6] Although the rooms were commodious and seemed to impress the usually nonimpressionable Domínguez, their layout was hardly functional in terms of direct circulation. "One must ride from this passage [in the convento next to the kitchen] on a hobbyhorse, because the stable, strawloft, oven and hencoop are not connected with the convent and church." The population counted sixty-seven families with 229 persons, a slight decline from the 1760 figure.[7] The church's prize possession was an altarpiece painted by Fray Ramón Antonio González in 1782, the same year he painted two screens for the side altars.[8]

Photographs from the 1880s taken from the side of the church show its incredible length. The nave appears as a prone figure, almost like a Gulliver tied down by Lilliputians, so elongated and grotesque is it in relation to the surrounding pueblo structures. The nave actually gives the impression that in ear-

9–2

Santa Clara

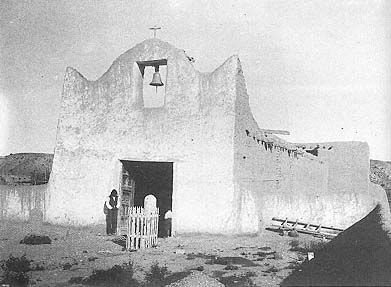

1899

At the turn of the nineteenth century Santa Clara looked much like Laguna

does today: a single bell arch, a flat facade, and two spikes at the corners.

[Adam C. Vroman, Museum of New Mexico]

9–3

Santa Clara

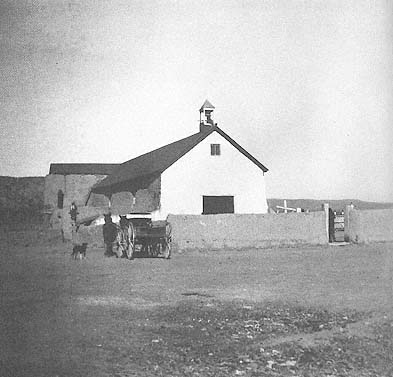

1904

The church uncomfortably wears the pitched roof that will cause its collapse.

[Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, Churchill Collection]

lier times it had once been both shorter and wider and that some supernatural hand had stripped its entry facade and stretched it across the dry earth. It stood that way into the twentieth century.

Lieutenant John Bourke, in 1881, noted in his journal:

My guides were anxious to show me the ruined church of "Santa Clara" and under their care, I made a brief examination. . . . The ceiling is formed of pine vigas with a flooring of rough split pine slabs, upon which is laid the earthen roof. In one arm of the transept, were a collection of sacred statues, dolls, crosses, and other appurtenances of the church. The altarpiece, though much decayed, is greatly above the average of church paintings to be found in New Mexico. It is a panel picture, with an ordinary daub of Santiago in the top compartment and a very excellent drawing of Santa Clara in the principal place. The drawing, coloring, and expression of countenance are unusually good and I don't blame the Indians for being so proud of their Patroness. A confessional and pulpit occupy opposite sides of the nave.[9]

Before 1903 it was decided that the chronically leaking flat roof should be covered by a metal pitched roof, which would solve the water problems once and for all, while the eastern facade would be trimmed with a crisp gable. The results, however, were not fortuitous. Earle Forrest told the sad tale:

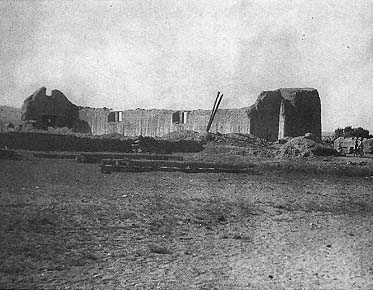

This great building was so massive that no one ever dreamed it would not stand for all time to come; and some twenty years ago [1909] when the destructive hand of the modern spirit reached Santa Clara, the work of remodeling the ancient edifice was started. The old roof was removed with its supporting timbers, and during a terrific storm the walls fell, the same as at Nambe, and this historic landmark was utterly destroyed.[10]

Prince's version of the events was more emphatic: "So the old timbers were removed and a modern roof placed on the adobe walls and alas! when the storm came, the great building which had withstood the vicissitudes of centuries fell with a great crash."[11]

The pueblo lived without a church for about nine years, and when a new building was erected, it "replicated" the old structure. That is to say, although possessing none of the extreme dimensions or proportions, it had roughly the same facial characteristics as its predecessor: flat, with two peaks at its corners and a small bell arch in the center of the pediment. The new church was built with transepts but without a pitched roof. Walter was heartened by the process, noting that we can "rejoice that the Pueblo at Santa Clara are rebuilding in the old way."[12] By 1962, in a photo published in a new edition of Prince, the hard cement stucco was shown badly peeling,

9–4

Santa Clara

circa 1910

Collapsing under forces exerted by the added pitched roof, the church

was in ruins.

[Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, Fred Harvey

Collection]

9–5

Santa Clara

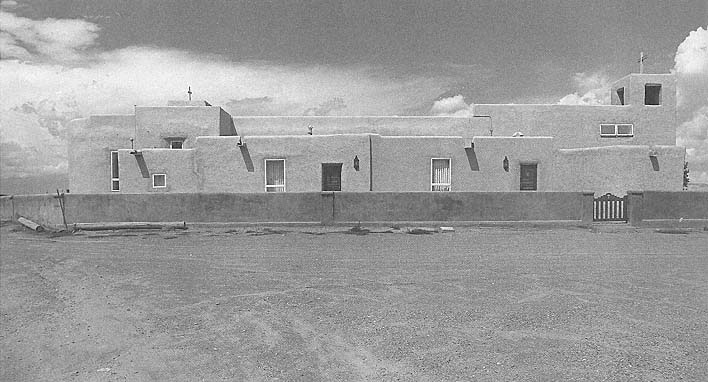

The new structure, although a much-reduced version of the church that preceded it, sprawls along the earth.

9–6

Santa Clara, Plan

[Source: Plan by John McHugh and Associates, 1978]

indicating that although the church was made of adobe, the fatal mistake of hard plastering had been made.[13] Sometime thereafter the church was remodeled. The single tower in the southeast corner of the facade seems to date from this time, as it is missing from the aerial photo of the pueblo published in Stubbs in 1950.[14] At least minor changes occurred between September 1976 and summer 1981: a pediment was added to the facade, and a window cut was added to light the choir loft.[15]

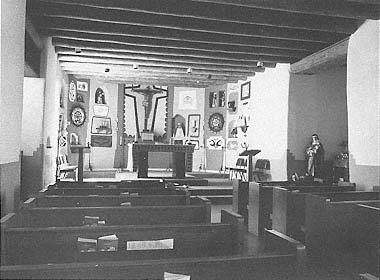

The present church appears somewhat forlorn, set off as it is from the remainder of the pueblo. Gray beige in color and surrounded by an earthen cemetery, only clusters of artificial flowers provide points of bright colors. The interior is just the contrast: long and low, perhaps in the old manner, it is now illuminated mostly by windows with milled window frames. Painted decorations line the walls, rendered a brilliant pink color (1981) in the sanctuary area. Sadly, there is no clerestory or increased elevation to the ceiling of vigas over the chancel areas. The feeling is low and heavy. But perhaps the composite feeling—low and oppressive—unwittingly recalls that of the "cannon" church on which Domínguez commented two centuries ago.

9–7

Santa Clara

The contemporary interior is low and long, enlivened by bright paintings

but no clerestory.

[1981]