San Ildefonso Pueblo:

San Ildefonso

(1617); 1711 (new site); 1905; 1969 (new structure)

Architects: McHugh and Hooker; Bradley P. Kidder and Associates

Some twenty miles north and west of Santa Fe, at the foot of the mountains, lies the pueblo of San Ildefonso. The architectural disposition of the pueblo and its plaza orients toward Black Mesa, which rises behind the community. San Ildefonso was little known as anything other than another pueblo until the rediscovery of the beauty of its pottery. Maria Martínez, who died some years ago, was the best known of the pueblo's potters, but she was only one of a number of makers of the elegant black, highly burnished, unglazed San Ildefonso ware.

Originally the pueblo featured two plazas divided by a block of dwelling units that were still visible in Stubbs' aerial view of the pueblo published in 1950.[1] The settlement of a dispute between the tribe's factions led to the block's removal, and the result today is a single plaza cut by the road leading to the church sited just off the northwest corner of the space. The freestanding kiva—one of the most beautiful of any pueblo—is still mud-plastered and blessed with a magnificently strong staircase that blends the pure geometry of its stepped profile with the softening influence of time on adobe.

Hewett dated the founding of the mission of San Ildefonso prior to 1601, although Walter was less specific and suggested that it was established some time before 1617.[2] Kubler listed no date for the founding of the first missions, giving only the 1680 date of its destruction during the Pueblo Revolt.[3] Whatever the exact date of its construction, the church was in place by 1629, the year of the Benavides visit. Although Benavides was generous in his evaluation of the Spanish efforts, church and convento still warranted the rating of "very spacious and beautiful"; Benavides also noted the positive influence of the irrigation water added by Fray Andrés Bautista.[4]

The church must have been in relatively decent condition at the time of the Reconquest, or it was rebuilt; there remained enough of it to be burned in the incidents of 1696 during which two priests were killed. The insurrection was rapidly quelled, but it was only in 1706, according to Kubler, or 1717–1722, according to Walters, that the church was reconstructed on a site just north of the original location.[5] This edifice seems to have weathered the remainder of the eighteenth century and most of the nineteenth rather well, until its deterioration in the latter part of that century. Tamarón mentioned little of the physical structure in the record of his 1760 travels. He did note, however, that there were ninety Indian families with 484 persons and "four families of citizens, with 30 persons."[6] The Domínguez description of San Ildefonso in 1776 reads al-

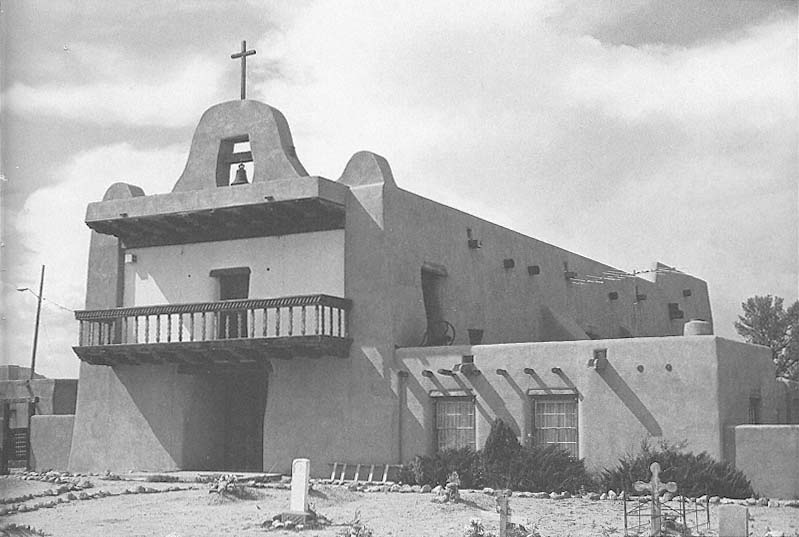

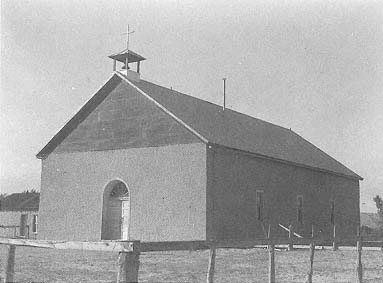

8–1

San Ildefonso

The new church replicates the form, if not the exact feeling, of its predecessor.

[1981]

8–2

San Ildefonso

The plaza with the church to the rear left.

[1981]

most as a generic description of New Mexican religious architecture of that period. Built of adobe and wooden roof construction, the church took the form of a single nave. Notwithstanding the clerestory and two "ill-made" windows that faced east, the friar noted that "this church is dark."[7] The structure faced south, with the baptistry extending to the east and entered under the choir loft, which extended across the south end of the nave. Curiously, the "whole wall around the sanctuary is painted blue and yellow from top to bottom like a tapestry, and not too badly."[8] Coloring an entire wall, rather than a wainscot, was rare in mission interiors and was probably intended to add a celestial and regal touch to the backdrop of the high altar, itself made only of adobe. Two additional altars faced into the nave at its sanctuary end.

The convento, situated to the west of the nave, took the form of a rough, enclosed square with a cloister "very pretty and cheerful, for it is square and open, with adobe pillars at the four corners and others in between in regular intervals, but of wood, carved with corbels above to imitate arches."[9] Much of these facilities, however, were in poor repair. At the time San Ildefonso contained 111 families with 387 people.

Domínguez credited Father Juan de Tagle with instigating and funding the improvements to the church's fabric. Fray Juan de Tagle "built and founded" the church and convento, its dedication taking place on June 3, 1711. Arriving at San Ildefonso in 1701, he remained there almost 25 years, "a most singular record in post-Revolt New Mexico, where missionaries, like the swallows, transferred almost with the seasons."[10]

By 1881 the church stood in poor condition. Bourke observed that the "church is very dilapidated and the rain runs through the roof in a perfect stream."[11] The traditional problem of water leakage through a flat, earthen roof with parapet was inescapable, and the temptation to sheathe the structure with a pitched metal roof must have been strong. Kubler recorded that the church was pulled down in 1905 and that a new church was built, possibly on the original seventeenth-century site adjacent to the dance plaza.

Writing in 1915, Prince told us that the church had been reconstructed after the 1696 difficulties and that it had continued in its rebuilt form "until a few years ago."[12] Three years later Walter concurred, although he might have used Prince as a reference, and assumed that "it was practically destroyed by alterations and mutilated by the construction of an ugly tin roof a few years ago."[13] Despite their con-

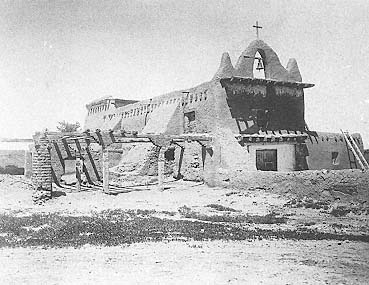

8–3

San Ildefonso

1899

The old church with its weathered belfry and immense buttress used

to support a sagging wall. The remains of the structure to the left,

probably a porter's lodge, may also have served as an atrio.

[Adam C. Vroman, Museum of New Mexico]

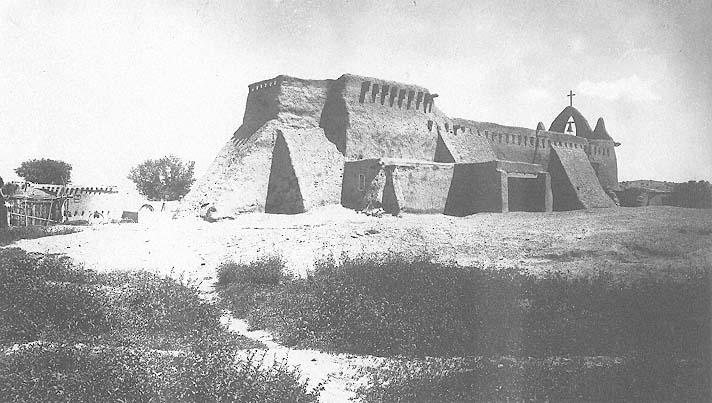

8–4

San Ildefonso

1899

The apse end of the church shows the buttresses bracing the west wall.

[Adam C. Vroman, Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives]

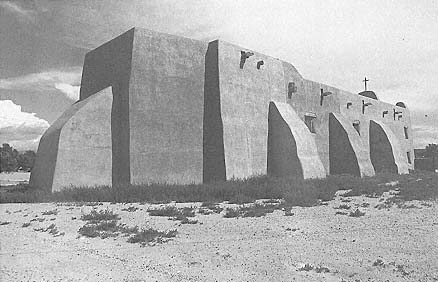

8–5

San Ildefonso

The apse end of the rebuilt structure.

[1981]

fusion about the nature of the new construction, both writers were troubled by the "more practical" form in which the church was built.

Whatever the exact date and whether it was a new church or not, Walter and Prince both expressed regret at the new construction, illustrating once again the continuing conflict between expedience and romance. The church in its 1905 form was a modern building and may have been the reason Kubler wrote nothing about the church in the text of his book but relegated it to a small mention in the chronological table. Kessell provided the definitive word on the history of the building by explaining the construction of a simplified structure in 1905 that replaced the badly deteriorated fabric of the old church, which was sustained primarily by the bulk of its eroding mass: "The 1711, 1905, and 1968 churches have all stood on the same site at San Ildefonso."[14]

One notable element in the church (visible in an 1880s photograph) was the "porter's lodge" that might have served at one time as an open-air chapel. Kubler mentioned that the chapel was placed perpendicularly to the main axis of the church, although Domínguez's descriptions referred to the appendage as a porter's lodge. Open-air chapels may have taken a modified form in New Mexico, but they continued a tradition that developed in sixteenth-century Mexico when the number of converts was extreme and the available space within religious structures severely limited. In theory, only Christians should enter the church for prayer. In the atrio, an enclosed courtyard that doubled as a campo santo, a small chapel was built as part of, or adjacent to, the main church. From this location services could be held, catechism could be directed, and a greater number of celebrants could be accommodated. The atrio represented a compromise between pragmatism and idealism; the courtyard was set off and defined as sanctified ground, although the full power and religiosity of an interior space were absent. An 1899 photograph of the San Ildefonso structure shows a simple three-bay construction of wood and adobe, which may have served a religious purpose, although this remains conjectural.

In the mid-1950s the question arose as to how repairs to the church should be carried out. Apparently the elements had so seriously undermined its physical condition that a major reconstruction was considered necessary. The simple tin-roofed building, so indicative of the practical, yet insensitive remodeling or constructions of the late 1880s through 1920s, possessed little character and little relation

8–6

San Ildefonso

after 1920

The remodeled church, closer in feeling and form to a New England

schoolhouse than to a New Mexican church.

[Museum of New Mexico]

8–7

San Ildefonso, Plan

[Source: Plan by John McHugh and Associates,

Architects]

8–8

San Ildefonso

The ceiling, looking toward the altar. The herringbone

pattern of latillas recalls the church of San José at

Laguna.

[1981]

8–9

San Ildefonso, Nave

Despite the windows on both sides of the nave, the transverse clerestory

provides the dramatic lighting characteristic of the New Mexican church.

[1981]

to the adjacent pueblo. The ultimate solution was to construct a new church in the form of the old one documented in early photographs. Of course, this approach raised questions of authenticity and intention. Would it be possible to recreate the aura of an old building without the original materials or the passage of time? Should the building replicate its predecessor or merely incorporate enough of the old features within a believable framework? Or should there be a new church built "in the spirit of tradition" but without slavishly imitating the old forms? All three approaches were problematic, particularly when the talent of the architect—and possibly the financial resources of the client—were limited. In the case of San Ildefonso, however, the story had a relatively happy ending.

Certainly there is no way to duplicate the feeling of adobe and mud plaster using cement stucco. The smoothness and imperviousness of hard stucco do not catch light or reflect time in the same way and to the same degree that soft mud plaster mixed with straw does. The purpose of stucco is to thwart time; it acquires the mark of history only through spalling and cracking. Mud, however, disintegrates unevenly, although more rapidly. There is a hardness to the look of stucco, and that it weathers evenly, rather than unevenly, ensures that the form of a church will not change drastically over the years. These properties are illustrated here in two photographs taken some eighty years apart. The softness and sensitive texture of mud are missing in the new structure. The towers and facade of the new church and the arch with its bell will never feel as comfortable and organic as the old structure; its edges will remain relatively precise, unlike the softened corners of adobe. Nevertheless, the merits and the suitability of the 1969 church, designed by McHugh and Hooker, Bradley P. Kidder and Associates, can cautiously be deemed a success.

The interior of the church is more convincing, however, because the vigas and the latillas that make up the roofing do continue the historic building tradition. The single nave and the prominent presence of the transverse clerestory return to the congregation some of the character lost in the 1905 rebuilding. The nave tapers in the apse end, visually extending its length, while the clear light falling on the altar creates the appropriate visual focus. The church faces roughly south, which guarantees a continual source of light from the clerestory throughout the day. To the east are a small convento and sacristy, and a campo santo fronts the church with its single cross.

The church of San Ildefonso lies in the northwest segment of the pueblo, neighboring the two plazas that have now become one. Traditionally dancers emerged from the darkness of ceremonial spaces, such as the handsome kiva at the south end of the plaza. Yet on saints' days, in the blending of Catholic ritual and native religions, the church was integrated into the dance. At Isleta, for example, the Christmas dance began in the church and was completed out-of-doors. Prince published one image of a dance at San Ildefonso in which the entry portal of the campo santo was clearly present in the photograph, demonstrating how the plaza space before the church was used for the dance. The presence of the church as the dominant structure in the community was unquestionable, yet the kiva remained more central ceremonially to the built fabric of the pueblo.