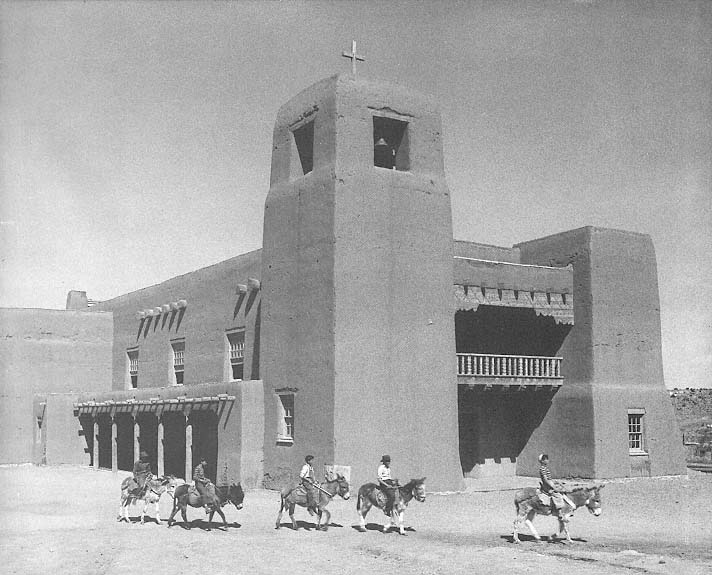

Cristo Rey

1940

Architect: John Gaw Meem

Although the Laws of the Indies did not specify that a church be built prominently on the plaza, neither did they proscribe its construction. And because the plaza was originally conceived primarily as a military space, it is not surprising that the chapel of the military confraternity should be built directly fronting the parade ground. It took some time, however —about a century to be more precise—before a chapel was built on the site.

During his term as governor (1754–1760), Francisco Antonio Marín del Valle purchased a lot on the south side of the plaza, facing the Palace of the Governors "between two houses of settlers."[1] He raised a chapel there for the sum of 8,000 pesos. Captain as well as governor, he had an interest in the project that probably exceeded piety. On this site a structure was erected with its facade toward the plaza, following the configuration of nave and transepts common to the Spanish towns of northern New Mexico.

As early as the 1620s Benavides had reported the paucity of church buildings in Santa Fe because the size of the population was small: "The Spaniards . . . may number up to 250. Most of them are married to Spanish or Indian women or to their descendants. With their servants they number almost 1,000 persons. They lacked a church, as their first one had collapsed." To rectify the problem, he had "built a very fine church for them, at which they, their wives and children, personally aided me by carrying the materials and helping to build the walls with their own hands."[2]

By the time of Bishop Tamarón's visit a century and a half later, the population had increased by about one-half: "I have confirmed 1,532 persons in the said villa, [but] I am convinced that the census they gave me is very much on the low side, and I do not doubt that the number of persons must be at least twice that given in the census."[3] Public worship was limited to the nearby Parroquia and the chapel of San Miguel across the river. Construction of the Castrense chapel was well under way, although building would not be completed for another year. Unlike the majority of churches in New Mexico at the time, this chapel would be highly embellished, receiving praises even from critical Mexican visitors. Tamarón witnessed the event:

In the plaza, a very fine church dedicated to the Most Holy Mother of Light was being built. It is thirty varas long and nine wide, with a transept. . . . The chief founder of this church was the governor himself, Don Francisco Marín del Valle, who simultaneously arranged for the founding of a confraternity which was established while I was there. I attended the meeting and approved everything.[4]

6–1

La Castrense Chapel

This redrawn detail based on the Gilmer map of 1846,

shows the Castrense chapel just south of the plaza. The

Parroquia (today the Cathedral of Saint Francis) lies to

the right of the original plaza, already filled in with private

buildings.

Written by Marín del Valle himself, the organization's constitution was approved by Bishop Tamarón during his visit, indicating that the founding of the confraternity postdated the chapel already under construction. Given what Domínguez termed "the fervent and glowing order of his devotion," it is no surprise that Marín del Valle was elected the first "Hermano Mayor," or "as we should now say, first president of the Society."[5] Work on both the altar screen and the body of the chapel continued during Tamarón's visit and were officially consecrated on May 24, 1761. Although officially the chapel was dedicated to Nuestra Señora de la Luz, or Our Lady of Light, it was usually known as La Castrense in reference to the military confraternity.

A considerable sum was to have been expended on the chapel interior, although the exterior remained the simple mud-plastered adobe common to the province. Most notable among the furnishings was the elaborate altar screen that filled the rear wall of the chapel. Under Marín del Valle's patronage, Mexican stone carvers, perhaps from Zacatecas, were imported to handle its crafting. "Eight leagues from there," Tamarón recorded, "a vein of very white stone had been discovered, and the amount necessary for the altar screen large enough to fill a third [of the wall] of the high altar was brought to this place. This then was carved."[6]

Domínguez, exceptionally, was just as impressed during his visit of 1776. His description noted that the structure "has walls about a vara thick. Its door faces north, and a little above it is a white stone medallion with Our Lady of Light in half relief. At the very top of the flat roof are three arches, a large one in the center with a good middle-sized bell, and a small one on either side without anything." A clerestory and a choir loft, both supported by "wrought beams" on corbels, were typical, although the carving was more elaborate than usual. Three windows faced east. Unlike the more normal wood-fronted steps into the chancel of most churches, however, "the ascent to the sanctuary consists of four octagonal stairs of white stone. The whole sanctuary is tiled with said stone, and there are three sepulchers in it."[7] The sacristy adjoined the east transept, its window to the south.

The focus of the interior was the altarpiece that dominated the rear wall.

The altar screen is all of white stone . . . very easy to carve. It consists of three sections. In the center of the first, as if enthroned, is an ordinary painting on white canvas with a painted frame of Our Lady of Light, which was brought from Mexico at the aforesaid Governor Marín's expense. . . . On the right side

of this image is St. Ignatius of Loyola, and on the left St. Francis Solano. Toward the middle of the second section is St. James the Apostle, and beside him, St. Joseph on the right and St. John Nepomuk on the left. The third section has only Our Lady of Valvanera, and the Eternal Father at the top.[8]

Originally, the entirety was polychromed in the tradition of the wooden altarpiece, and the architectural framework of the screen was filled out with Arabesque columns and entablatures. The effect, Domínguez noted, was that the altar screen "resembles a copy of the facades which are now used in famous Mexico."[9] Two altars of stone, like the altar screen, stood in the transept. "Its interior is very attractive," Domínguez said in summation.[10] Given that his opinion of the villa of Santa Fe was that it "lacks everything," this was no mean compliment.[11] The effect of the altarpiece was never equaled in colonial New Mexico, although its design served as the basis of many painted altar screens thereafter.[12]

The chapel was set back from the south limit of the plaza, fronted by a campo santo apparent in the simple Urrutia map of 1768. Six years later de Morfi provided fewer details but showed a bit more respect for the villa: "The plaza," for one, "was square and beautiful. A chapel consecrated to Maria Santisima de la Luz [Most Holy Mary of the Light] also adorns it [the plaza], where was established the parish of the military which a religious served since 1779, the year [of its erection and other private buildings]."[13] As the chapel was completed in 1761, this was either an error or a reference to a renovation, possibly the construction that added the two towers and balcony to the north facade, commented on by nineteenth-century observers.

By the end of the century the walls and roof had badly deteriorated, and in 1805 Fray Francisco de Hozio requested funds to make "repairs necessary for the decency of the divine worship."[14] The official visitor, Juan Bautista de Guevara, in a lengthy report, was "deeply saddened by the 'ruinous and lamentable state' to which the confraternity had sunk." His document, however, did record that "across its entire facade looking toward the plaza there is a gallery of six sections with columns and a wooden roof; two small adobe towers with wooden tops, all old and falling down."[15]

Services were well attended and treated with some degree of pomp. "During the first government of Manuel Armijo (1827–29), he went regularly with the whole garrison force of Santa Fe in full uniform to attend services there."[16] Although the chapel remained intact through the 1830s, this was to be the last period during which most of its

6–2

La Castrense Chapel

The upper portion of the stone reredos sponsored by Antonio Marín del

Valle, now in the church of Cristo Rey.

[1986]

previous glory remained. When the new republic of Mexico withdrew stipends for military chaplains, the Castrense lost its congregation.[17]

James J. Webb, a trader visiting Santa Fe in 1844, wrote that the "old church about the centre of the block on the south side of the plaza . . . has not been occupied as a place of worship for many years."[18] The chapel was not to have a quiet end, however—at least not yet. The military continued to support its upkeep with occasional repairs, however sporadic. At the time of the American entry shortly thereafter, the building was in derelict condition. Lieutenant Abert described the interior as having been

the richest church in Santa Fe. . . . There is some handsome carved work behind the altar, showing a much higher order of taste than now exists. . . . One finds the bones of many persons scattered about the church. These belong to wealthy individuals who could afford to purchase the privilege of being beneath the floor where so many prayers were offered up; but they have not found as quiet a resting place as the poor despised publicans. The roof of this church fell in a few years ago and it has not been used since.[19]

The United States Army acquired the use of the church, repairing the roof and using it for storage until 1851, when Justice Grafton Baker sought a suitable location to conduct due process. He eyed the property and began the process of adapting the storage buildings as a court of law. Surprisingly, given the dilapidated state of the chapel, he met with considerable resentment from the citizens, who cited the burials within the building as reasons not to use the chapel for civil purposes. Baker held his ground and the controversy grew. After one judicial session, however, an agreement was struck that passed the chapel back to the diocese. Bishop Lamy, after receiving the keys to the building, called for a subscription to repair the chapel. His efforts were successful, and the building was at least partially restored during the next few years.

Lamy had problems of his own. As an avid supporter of education he had formulated a rigorous program of instruction and school building. He had also set his mind on the construction of a stone structure to replace the adobe Parroquia that was now his cathedral. Both programs required money. In an effort to raise the necessary capital for the repairs and land for a school, he sold the Castrense in 1859 to Don Simón Delgado, who built a house on the site. In turn Lamy was given $2,000 by Delgado and a plot of land for Saint Michael's College.[20] Parts of the structure remained until 1955, when

6–3

La Castrense Chapel

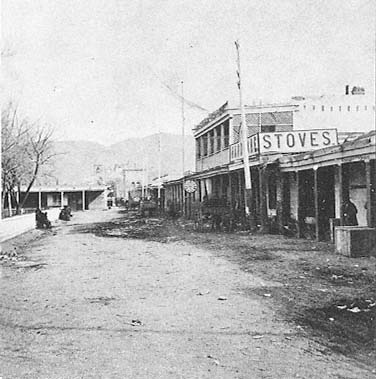

In this photo taken around 1877 the old chapel has been converted into

a store, with a latticed terrace addition at the second-floor level. The

beam ends still protrude through the adobe wall, and the new cathedral

is rising at the end of San Francisco Street.

[Benjamin H. Gurnsey, Museum of New Mexico]

demolition of the chapel was complete.[21]

The noted stone altarpiece of Nuestra Señora de la Luz was moved first to the cathedral, where it was kept until the church of Cristo Rey was built in the late 1930s. There it remains, but with only traces of its original polychromy, its force partially diminished by the much larger scale of the new structure.

Three factors contributed to the construction of the new church. The first was the interest of the Committee for the Preservation and Restoration of New Mexico Mission Churches in finding a new home for the stone altar screen from the Castrense. Since the 1860s the screen had been "stored" in a space behind the altar of the cathedral in a state of benign neglect. Second, when Reverend Rudolf Gerken became archbishop of Santa Fe in 1933, he found the need for an additional parish on the city's east side. A site was purchased on upper Canyon Road, John Gaw Meem's firm receiving the commission for design in 1939. The third factor was the four hundredth anniversary of Coronado's expedition through the Southwest. At a dinner in the cathedral rectory on April 6, 1939, Archbishop Gerken announced the commencement of the project: "We shall build a memorial to the Coronado Centennial in the form of the most beautiful church in the Southwest. This memorial will become a new parish."[22] For a project of this size, the design process must have proceeded rapidly, although there never seemed to have been any question as to the style of the structure.

The appearance of the church is traditional, but its form somewhat belies its construction. Although Cristo Rey is principally an adobe structure—with the number of bricks estimated at between one hundred fifty and one hundred eighty thousand—it is not a pure bearing-wall building. In response to the loads that the walls had to carry and the span of the nave, the adobe structure was augmented by a structural steel frame that not only reinforced the walls but also carried a portion of the vigas of which the roof was made.

The craft is of the highest order throughout. The corbels supporting the vigas are finely carved, and the split juniper logs, or cedros , that form the ceiling are carefully fitted. The exterior departs from the rigid symmetry of the interior composition, freely utilizing inspiration or forms from a number of historical structures. As Bainbridge Bunting noted, "It has the grand scale and at least one tower of Acoma, the balconied facade of Trampas, the transepts of the old Parroquia of Santa Fe, and the effective transverse clerestory of Santa Ana."[23] The totality escapes the level of pastiche, however, and evidences a coherent architectural idea executed with understanding and skill. The church received the archbishop's blessing on January 1, 1940, and was formally dedicated later that year on June 27.

When judged against the ideal, the church as the home for the Castrense altarpiece has two short-comings. The first is the size of Cristo Rey, which is of a grander order than the historical chapel. The effect of the reredos seen from the distance, surrounded by larger walls, is just not the same, being diminished by the size of the space. The second is the greater level of illumination, which from windows as well as skylights at times undermines the drama created when only a clerestory transmits light. Despite these minor criticisms, the fine Castrense reredos is again accessible to the public, and it lives once more within a church, not a museum.

6–4

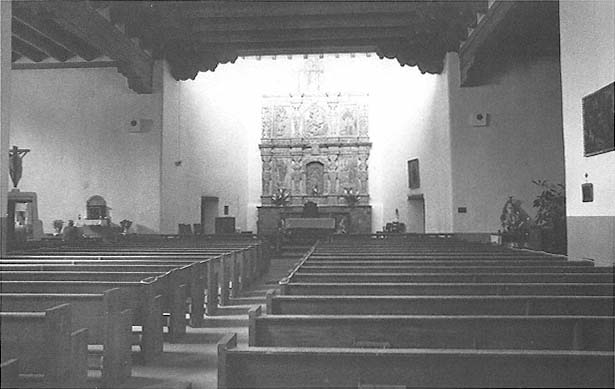

Cristo Rey

In spite of the large scale of the church, the effect of the clerestory light falling upon the reredos remains effective

and dramatic.

[1986]

6–5

Cristo Rey, Plan

[Sources: sketch plan by John Gaw Meem, University of

New Mexico Library Special Collections; and measurements

by Dorothée Imbert and Marc Treib, 1986]

6–6

Cristo Rey

May 1942

Shown three years after its completion, the church displays far greater subtlety in its mud plaster modeling than in

today's hard stucco.

[New Mexico Tourism and Travel Division]