Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

1795?; 1808?–1821

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe is one of those adobe churches that has changed so radically over time that recognizing it in uncaptioned photographs would be difficult. The church appears neither on the 1766 map by José de Urrutia nor in the Domínguez report of about the same time. The exact date of its origin remains a bit of a mystery, although it was probably built at the very end of the eighteenth or early in the nineteenth century because a license was issued for its construction in 1795.[1] The map of the city by Jeremy Francis Gilmar drawn in 1846 shows the plan of a cross-shaped church and campo santo on the site, but no tower. (The Castrense chapel is also shown without towers, however, suggesting that the church was rendered symbolically rather than literally.)

Father James H. Defouri, who administered the parish in the later nineteenth century, may have been the source for Ralph Twitchell's claim that the church dates from before the Pueblo Revolt: "[In 1680] Guadalupe being somewhat out of town fared better for a while, but was sacked the following year."[2] Except for these undocumented assertions, there is no recorded evidence of the church's existence or description until 1821, as Kubler noted, when it was visited by Agustín Fernández after Mexican independence. Having been omitted in Pereyro's inventory of 1808, Kubler ascribed its construction to the period between 1808 and 1821.[3] From then on the church suffered the normal pattern of ups and downs.

When the Americans took control of the city in 1846, the year of the Gilmar map, the church was sadly dilapidated, although Abert reported that it had been in use until as late as 1832.[4] An 1886 map now in the Museum of New Mexico illustrated the church in a vignette with typical New Mexican massing, stepped up at the choir and transepts to admit a transverse clerestory, and, of course, made of adobe. There was a three-stage tower similar to the old bell tower at San Miguel that was destroyed in the 1880s, but it was placed off center, to the east of the main door. Lieutenant Bourke confirmed the church's ruinous condition in 1881:

It shows great age in its present condition quite as much as in the archaic style of its construction. The exterior is dilapidated and time-worn; but the interior is kept clean and in good order and in very much the condition it must have shown generations ago. The pictures are nearly all venerable daubs, with few pretensions to artistic merit. At present, I am not informed upon this point and cannot speak with assurance, but I am strongly suspect that most of them were the work of priests connected with the early

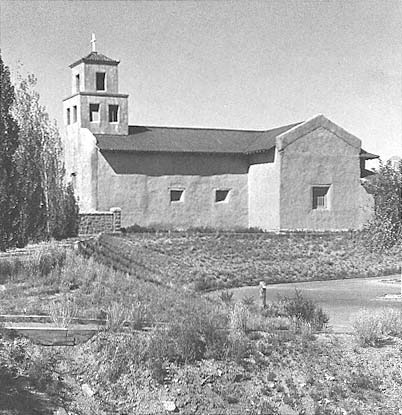

5–1

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

The renovations of the 1970s converted the church into a performing arts

center and gallery, although there were no attempts at a precise historical

restoration.

[1981]

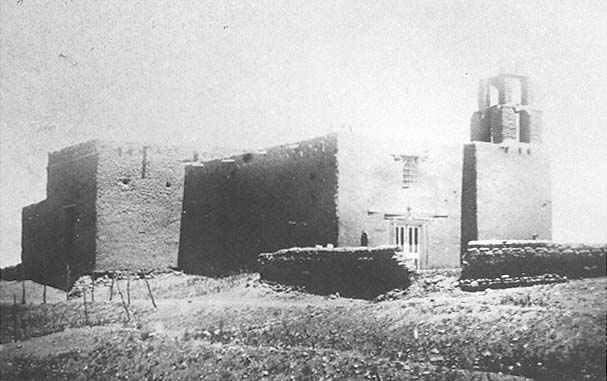

5–2

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

1881

The single tower, with its massive base, cast the church into asymmetry; its stepped profile resembled the old San

Miguel chapel.

[W. H. Jackson, Museum of New Mexico]

missions of Mexico. Many of the frames are tin. The arrangement for lighting this chapel are the old-time tapers in tin sconces referred to in the description of San Francisco and San Miguel. The beams and timber exposed to sight have been chopped out with axes or adses, which would seem to indicate that this sacred edifice was completed or at least commenced before the work of colonization had made much progress.[5]

At that time its only official services were held on December 12 at the annual festival of Our Lady of Guadalupe.[6] The church also seems to have been used for Protestant services in the 1880s under pressure from Anglo immigrants.

The growth of mining in northern New Mexico at that time also brought an influx of Catholics who, although centered around Cerrillos, petitioned for an English-speaking congregation in Santa Fe. About 1881 Reverend James H. Defouri was placed in charge, and like Saint Francis centuries before, Defouri energetically went about putting God's house in order. L. Bradford Prince noted that new windows, made available by the railroad, were installed and that a typical, although light-smothering, pitched roof of shingles was added. Capping the new incarnation was "a wooden spire of the strictest New England meeting house pattern in the place of the venerable tower."[7] Pews graced the new wooden floor. The transformation was so complete that had it been worked on a child, even its mother would not have recognized it—which was, no doubt, the intention.

A fire in 1922 destroyed the roof timbers of the sanctuary and transepts as well as the alien steeple. By then the popularity of the California Mission style had begun to work its romantic magic on the populace, and Guadalupe was accordingly rebuilt with curved shoulders supporting a two-staged tower with proper arched openings. Although not accurate in terms of historical precedent—as was clearly visible in the sloped tile roof—the new form fit better into the architecture of Santa Fe than had its dilute Gothic predecessor. On the interior a single arch spanned across the altar, somewhat elevating the character of the historic adobe structure.

5–3

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

April 1881

Like the exterior of the church, the interior underwent extensive changes

at the end of the nineteenth century. In this early photo the accretions

and clutter of votive offerings are apparent.

[Ben Wittick, Museum of New Mexico, School of American Research

Collections]

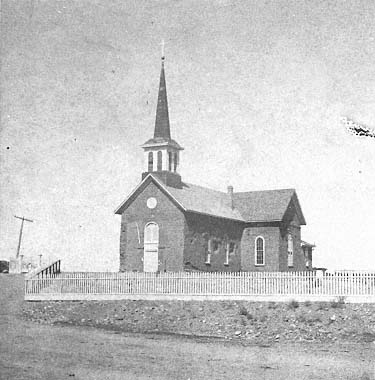

5–4

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

circa 1887

At the end of the 1880s the new pitched roof and belfry gave the church

the look of a New England schoolhouse.

[F. A. Nims, Museum of New Mexico]

Guadalupe became an auxiliary of the cathedral parish in 1918, but its status as a separate congregation was restored in 1931. A new church was constructed south of the original structure in a sympathetic, if not historicist, style. What was to become of the old building? For some time it functioned as a chapel. Through the initiative of Archbishop Robert Sánchez, however, the old church was restored for use as a museum of Spanish Colonial art and, when appropriate, as a performance center for chamber music and recitals. The Santa Fe architectural firm Johnson-Nestor directed the restoration, which was undertaken during the years 1976–1978.

The building has not been restored but has been significantly remodeled; the tile pitched roof still conceals the clerestory. The tower has been revised to a more severe form, with square openings using wooden lintels to replace the former arches. Throughout the interior and exterior the inappropriate aspects of the 1920s rebuilding have been removed and the architectural entirety simplified. A small watercourse leads toward the river as a tentative gesture toward establishing a link between the old church and downtown. While this remodeling is neither complete nor accurate in an archaeological sense, the current state could best be termed sympathetic and successful in feeling, if not in form.

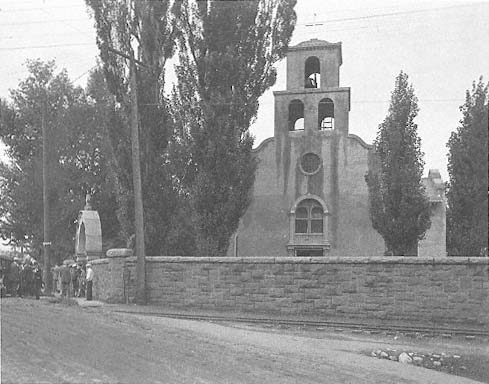

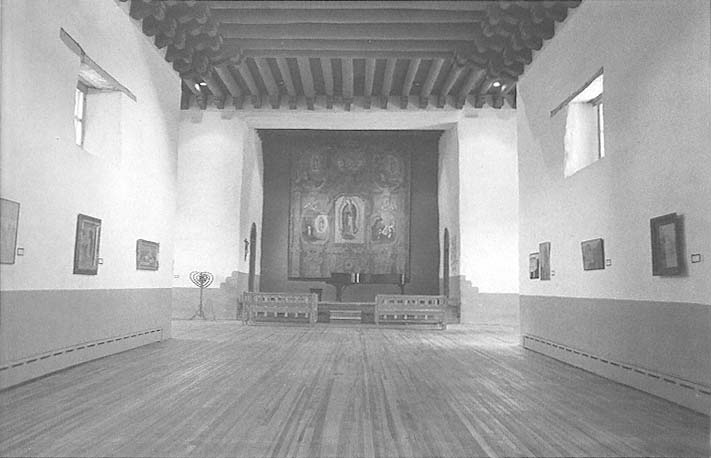

5–5

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

circa 1920–1925

By the late 1920s a central belltower had replaced the Anglo belfry, and a California Mission

style had glazed the church.

[T. Harmon Parkhurst, Museum of New Mexico]

5–6

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, Plan

[Sources: Plan by Johnson-Nestor, Architects; and measurements

by Susan Lopez, 1987]

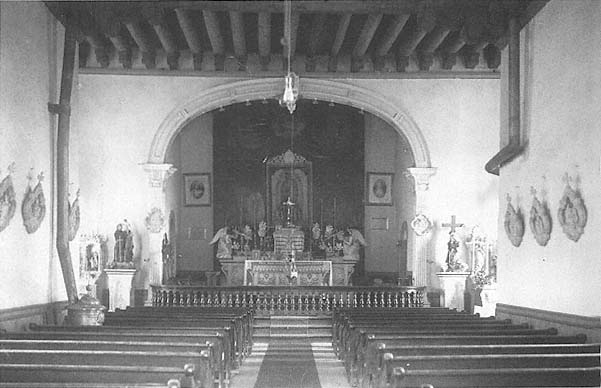

5–7

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

circa 1920

Victorian clutter has superseded the Hispanic; but the arch spanning the chancel reveals an influx of Anglo

architectural taste.

[T. Harmon Parkhurst, Museum of New Mexico]

5–8

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

The state of the interior after renovation: Spanish colonial architecture in a simplified form.

[1981]