Furnishings and Decoration

Hispanic colonial buildings had no closets. In fact, spaces for storage were not included within the house except in rooms used for agricultural reserves or wares related to the farm. Domestic goods were stored in wooden or rawhide chests, which were either horizontal with hinged tops flat or arched or upright with hinged doors. Furniture of this sort—first imported as traveling trunks but later domestically produced—offered surfaces for carved or painted decoration. In certain instances, particularly for domestic purposes, the chest might double as a table: ornament and show, not comfortable sitting, were the main considerations.[104]

In these chests everything was deposited. Domínguez commented on the need to secure all the church possessions, poor as they were. His recordings of the holy vessels as well as all the furniture and furnishings only pointed out how barren and destitute the churches actually were at the time. Had they been repositories of ecclesiastical treasure, a comprehensive list of the contents would have been a formidable task, or an abridged inventory might have sufficed. But the friar did list the complete stock of the church, and in the end, the list was not long. Although the floors were of earth and Indians stood in their churches throughout the service, Herbert Bolton reported that to increase the prestige of the governor, alcalde, and council, "Separate benches were placed in the churches" for them, implying that seats did exist in the Spanish churches.[105]

Just as the possessions of the church were meager, so were its decorations. Missing were the ex-

tensive ornamental programs of central Mexican church interiors. On the plastered surfaces of the walls decorative patterns were brushed. At the ruins of Jemez Springs as well as at Abo excavated fragments of red and black paintings suggested an intention to ornament church interiors from the earliest construction period. But the first decoration, if it can be called that, was probably whitewash applied to the interior of the church or to the facade or all the exterior. And in a landscape of earth tones, the power of the color white is considerable. Prior to its recent collapse, the facade of Picuris, for example, palpitated visibly, so striking was its contrast with the remainder of the earth-red church and its surroundings [Plate 12]. Laguna and Zia—the former stark white, the latter a rusty golden cream—are dazzling counterpoints to the rubicund surrounding landscape. And the orange-brown and white vertical stripes of San Jerónimo at Taos pueblo further the elaboration, although the color scheme is from this century and is executed with commercial paints.

Beyond this basic chromatic tinting, facade decorations included geometric or animal motifs, two outstanding examples of which are the churches of Santo Domingo and San Felipe. In both instances animated images of horses appear above the serrated wainscot with brilliantly colored geometric designs that recall the ornamentation of ceramic vessels. Although these paintings are of recent execution, their images stem from and continue a centuries-old iconographic tradition.

Decoration also finished the naves of many churches. Early builders applied to the walls a lightly colored wainscot of whitewash prepared by baking limestone, plastering with a white sandy soil known as tierra blanca or with a yellow tierra amarilla that sparkled with mica flakes. The sanctuary of San Ildefonso in the late eighteenth century was "painted blue and yellow from top to bottom like a tapestry."[106] Upon these painted surfaces geometric patterns might be added, such as those at Acoma, whose designs recalled the motifs used on the pueblo's noted pottery. Floral and animal motifs were also common. The painted wainscot not only addressed the functional problems of wear; it also provided a visual base of reference against which the apparent scale of the nave increased.

In addition to the simple and delicate pink-tinted wainscot paintings at Acoma, the boldly painted interior decoration of San José at Laguna is also noteworthy. The white walls of the nave host painted abstract and animal images in red, green, and black; when taken together as a progression, these images

1–32

San José

Laguna pueblo

The ornamental program is executed in red and black paint on the whitewashed surface of

the walls.

[1986]

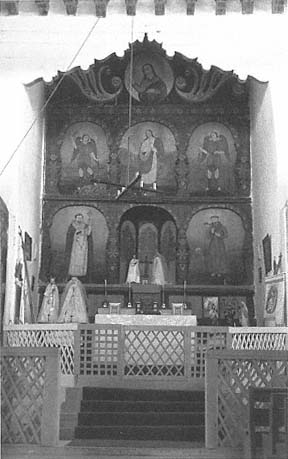

1–33

San José

Las Trampas

The main altarpiece, attributed to José Gonzáles.

[1981]

provide a rhythm that binds the entrance to the altar. The ceiling latillas are turned obliquely to the vigas, forming a herringbone pattern emphasized by selective painting in red, white, and black. And in its totality the Laguna church comes the closest of any mission in the state to possessing a unified decorative program, which extends beyond its wall paintings and ceiling to a fine altarpiece and paintings. The choir loft of Santa Clara is also lavishly painted in bright colors, but the size and intensity of the designs are not in complete sympathy with the intimate scale of the nave. As a result, the interior lacks the unity and harmony of pictorial devices found at Laguna and Acoma.

The ritual focus of the church was the high altar, which was centered in the nave and marked the sanctuary area. Although the altar could be made of as simple a material as adobe, or more politely in stone, its surface was always intended to be covered by a cloth. Linens and other fine fabrics accompanied the missionaries from Mexico or might have been shipped on subsequent supply trains or borrowed from other churches when a new mission was founded. Native weavings could grace the interiors; parishioners might have donated examples of their own crafts as acts of devotion or social display.

Upon these cloths rested the regalia of the sacred service, and here at least was one surface able to rise above the roughness imposed by frontier conditions. Or perhaps there were two surfaces. Although the altar was the heart of the church, the altarpiece, or reredos, provided a suitable backdrop to the divine rite. [Plate 7] The reredos was a didactic instrument, narrating in images the stories of the saints, illustrating vignettes from their lives, and depicting their portraits, attributes, and, perhaps, martyrdom. Rather than a single, large painting, the altarpiece comprised a series of separate panels joined together in an architecturally treated frame with the images in each panel painted, usually in tempera, on gessoed wood. In later periods the framework containing the paintings was elaborately worked and colored and rivaled the painted images themselves in intricacy and beauty. The iconography of the reredos derived from European and Mexican precedents, although those painted in the severely constrained conditions of New Mexico were of necessity relatively fundamental and naive. Frequently a dark contour line outlined the image, suggesting its derivation from printed sources such as engravings, woodcuts, or books on biblical subjects. The wooden engraving, for example, relied on a style of rendering that used thick outlines to retard deterioration by continuous impressions. Early santeros , the

1–34

God the Father

Rafael Aragón

The painting of religious images during the nineteenth

century was characterized by a simple outlining that

resembled prints produced from woodblocks.

Expression derived from linework and gesture rather

than from careful modeling or accurate resemblance.

[Taylor Museum, Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center]

makers of sacred images, employed similar techniques that relied on line rather than on the elaborate modeling of form.

In many areas beyond those generating primary cultural and artistic change, the portable book provided the principal source for images. Since the woodblock and, later, the engraving were the dominant modes of graphic reproduction, their characteristics necessarily influenced artists who sought inspiration from them. This reliance on line, rather than on modeling, considerably simplified the act of painting by enabling a two-stage execution: the first stage determined the form; the second, its rendering. Although complementary, the two stages did not have to be absolutely congruent, as would have been the case without use of the outline. A simplification in tone and intention paralleled the shift from modeling to line.[107]

Of course, exceptions to this approach did occur, most notably in the work of the so-called Laguna Santero credited with the altarpiece of that church (c. 1803—1809).[108] The Laguna altarpiece is a splendid and exuberant work that combines the secular imagery of the moon and sun on a panel inclined above the principal reredos with religious images of San José, the patron of the church, Santa Bárbara, and others [Plate 10]. Because depictions are conveniently ambiguous, these celestial subjects could derive from the Laguna religion, or they could just as easily relate to Saint Francis's Brother Sun and Sister Moon. Although the nave is dark and without the benefit of a clerestory, the colors of the paintings display an intensity that conveys gripping conviction: to a member of the congregation the reredos must have had an almost hypnotic effect, rendering the presence of the saints almost tangible.

Usually a reredos stood in each transept facing toward the nave, whereas in single-nave churches secondary screens were mounted on the walls just before the sanctuary. In the church of San José at Las Trampas, however, there are five separate reredoses: one behind the high altar, two at subsidiary altars in the transepts on either side, and two more now within the nave itself. Each supersedes the previous one in size and lavishness. These paintings date to the late eighteenth century and include images of the more popular Franciscan saints as well as Santiago (Saint James the Greater), a military figure who led battles against the Muslims and whose spiritual presence would have aided in the battles in the New World against hostile Indians. At Santa Cruz, Fray Andrés García worked from 1747 to 1779 carving and painting pulpits, altar rails and

1–35

San José

Laguna Pueblo

Detail of the principal altarpiece with its mixture of Christian and possibly native iconography.

[1986]

screens, and religious images.[109] Other exemplary paintings can be found at Chimayo, Acoma, and Ranchos de Taos.

More basic were paintings executed on animal hides, used throughout New Spain when wood and canvas were not available. Buffalo, elk, and deer provided the most common surfaces, the images being rendered in vegetal dyes or water soluble paints.[110] E. Boyd underscored the role of Mexican precedents for this genre, particularly in years following the Reconquest, when the hide paintings bore a distinct resemblance to wall paintings: "The Franciscans who then came to New Mexico had been stationed at one or more of the 16th century churches built in New Spain, such as those at Acolman, Actopan, Cholula, and Huejotzingo. These had extensive frescoes in their convents and churches in the Renaissance manner and must have been the sources used from memory by New Mexican missionaries."[111]

Although Domínguez was critical of many aspects of the church furnishings, he appeared remarkably open-minded in estimating the worth of paintings on hide. In the inventories of most churches he merely recorded that the paintings used animal skins, rather than canvas or wood, for their substrate and even conceded that the sacristy of San Ildefonso had "a white buffalo skin painted with flowers and very pretty."[112] Juan Bautista de Guevara (whose visitation extended from 1817 to 1820) was hardly as accepting: "The painting of Santa Barbara on elkskin (at the parroquia in Santa Fe) must be removed and done away with completely as it is improper as an object of veneration and devotion of the altars."[113] His condemnation was reinforced by Jean-Baptiste Lamy, the bishop who arrived in the mid-nineteenth century.

As an expression of faith these paintings could not be faulted, but the nature of their ground, the hides of animals, was deemed "indecent" and unacceptable. In the field missionaries maintained a pragmatic flexibility necessary for survival under frontier conditions. Official visitors, however, gauged the appropriateness of the paintings against an absolute standard and found them wanting.

The earthen floor of the nave was at times covered with rugs, usually of Indian manufacture. The sanctuary of Laguna still contains weavings of various designs that, when grouped with altar cloth and reredos, form a decorative ensemble of considerable richness and complexity.

Being imported, worked metal was scarce in New Mexico, although ore was later found in some distant parts of the state. Early explorers were uninter-

ested in those minerals whose monetary return was not immediate. Although silver mines rewarded their investors with considerable profit, their portion of the state's history was played out mostly in the nineteenth century. Iron was used and reused for functional purposes; decorative metalwork remained relatively rare. Where possible, connections utilized alternate means, such as wooden pins or rawhide ties, to substitute for iron.[114] Early on the Franciscans taught smithing to the Indians and were so successful that during the Reconquest the Spanish found an operating blacksmith shop at Sandia pueblo. New Mexican blacksmiths produced a full variety of iron products from military supplies to construction and household articles that included lances, awls, hinges, latches, and ploughs. That the mission under Fray Estevan de Perea had acquired much of the imported iron was verified by a complaint to the viceroy by the municipality of Santa Fe. The missions had received so much of the available iron that scarcely enough remained for civilian needs, such as agricultural tools and horseshoes.[115]

At its founding, a mission was endowed with a standardized list of construction products such as locks and fittings, furnishings, and devices for mass. France Scholes provided a list of these supplies, from which the following has been excerpted and from which we can derive a sense of the inventory of the early missions:

For each new mission: cloths; 1 bell; iron framework for bell; oil painting of saint; cupboard for chalice; rug for altar steps; crucifix; for every five friars, iron for making wafers; and a set of trumpets. For each friar for building his church: 10 axes; 3 adzes; 3 spits; 10 hoes; 1 medium saw; 1 chisel; 1 latch for the church door; 2 augurs; 1 plane; 10 lbs of steel; 600 tinned nails for church doors; 4000 assorted nails; 800 tacks; 2 small locks; 1 dozen hinges for doors and windows; 1 dozen hook and eye latches; 1 pair braces for the two doors.[116]

Although intended as minimum provisions for a consecrated church, the list more commonly remained incomplete. Too many factors intervened to prevent fulfillment, from the staging of the goods in Mexico City to the long overland route threatened by humans and nature. Since supplies in the northern province were always at a premium, continued consultation and borrowing among the missionaries were the normal course, and competition was kept to a minimum, especially when compared to the competition among church, military, and civilian authorities. On the whole all metal, even iron, was treated as a precious substance. The eighteenth- or early-nineteenth-century hinges, straps, and grills extant demonstrate the settlers' ability to produce high-quality goods even when the availability of metal and the methods for working it seemed to preclude doing so. The church remained to the end a structure primarily of earth and wood, however.

The most noted fragment of metal in the church's fabric was neither of iron nor of silver but of bronze. This was, of course, the mission's bell, which in time became the symbol of the church. The bell, with the drum, brought the Indian to catechism or worship and was most often fabricated in Mexico or Spain and brought to New Mexico on supply caravans. Even a military expedition, like those of early exploration, carried a small bell among its supplies so that its Franciscan chaplain could celebrate mass en route. In certain inventories a bell was described as "a gift from the king," a reference to the practice of paying for the bells from Royal Fisc funds provided for the continuance of the missionary program. Domínguez, in his fastidious fashion, noted the existence or nonexistence of the bells in the churches he visited, assigning to the bell cultural qualities beyond the economics involved.

In the simpler structures the bell was tied with rawhide to the wooden lintel of a small opening within the pediment crowning the facade. In the churches with twin towers, one or both of the towers could be used as belfries. A more unusual arrangement is that of San Miguel, where one muchaltered tower is centered in the facade above the main entrance. At the turn of the century doors or louvers were installed in the tower, thereby partially screening the bells from view but allowing their sound to resonate.

Bells, their mountings, and their soundings continued to be problematic. Since bells were often cast without clappers, a rock was used as a substitute. Striking the bell required the sacristan or his assistant to mount the roof of the church or belfry, which was rarely an easy task given the uncoordinated planning of the church and convento circulation. Even the bells of Santa Fe's principal religious structure, the Parroquia, could be reached only by ladder. The motion of a swinging bell held in place by rawhide also took a toll on its adobe supports. Even if the lintel or arch was strong enough to withstand the forces of bell ringing, the forces of nature still held sway; rawhide ties wore, rotted, or snapped. Photographs illustrate that towers and bell arches, at San Felipe or Santa Clara, for example, were always the first part of the building to suffer erosion by wind and rain. As a result, some churches resorted to methods first used before churches were

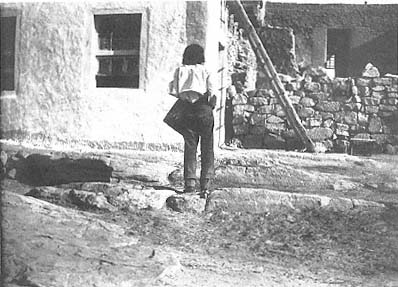

1–36

San Esteban

Acoma Pueblo

The drummer calls the congregation to prayer.

[George H. Pepper, 1903; courtesy Museum of the American Indian,

Heye Foundation]

built in the area: they kept their bells at ground level, supported by a wooden framework.[117]