Illumination

New Mexican architecture is an architecture of both mass and light: the structure itself is little without the radiance that imparts visual life to the inert soil. As Charles Lummis wrote of New Mexico's light, "One cannot focus upon sunlight and silence; and yet without them adobe is a clod."[87]

Today we find beauty in these structures' simple volumes, striking profiles, soft textures, and vital, if rudimentary, ornamentation. But in the creation of a sense of sanctity and significance within the church, light was the critical ingredient. If the vault and the dome were nonexistent in New Mexico, and if elaborate, gilded decoration was impossible to procure, then brilliance and sparkle had to be created by other means. Pueblo rooms were dark [Plate 17]. Lacking glass, the Indians made small eyelike windows of flaked mica stone called selenite, at least one example of which still remains at Acoma. The Spanish brought glass in small pieces into the province, but glass was a precious commodity because it had to be transported overland from Durango or Chihuahua. Hence its use was not widespread. More commonly Spanish church builders used oiled hides or adapted the native practice, creating windows of translucent selenite set in wooden grills that admitted a soft and diffused light.[88] The individual units rarely exceeded five inches square, however. Even with the opening of trade in American goods during the Mexican period, the size of the panes remained limited. Shipping invoices that served as customs declarations for a shipment of products from St. Louis in 1854 listed glass of only eight by ten inches and ten by twelve inches. Presumably, only smaller panes could be economically produced and transported by wagon.[89]

George Kubler, in his pioneering work The Religious Architecture of Early New Mexico , asserted that the transverse clerestory was the most characteristic invention of the New Mexican church.[90] He suggested that the clerestory was a vestige of the Mexican cupola, a form unattainable with New Mexico's limited technology and materials. The light quality and configuration of the church's cross-section, however, recalled more closely the stepped roofs of Moorish construction, such as the mosque at Córdoba, Spain, begun in 785 and converted into a Catholic church in the thirteenth century at the time of the Reconquest. The mosque's space comprised a seemingly infinite number of bays spanned by horseshoe arches that disappeared into the murky distance. A series of linear clerestories provided strips of diffused illumination running nearly the full length of the mosque. Its soft and indistinct lighting and the strength of its structure were recalled in the New Mexican nave.

Raising the ceiling height between the nave and the choir area in the New Mexican church introduced a slit of light that, with care and luck, would fall directly on the altar. The effect of this device can be stunning and is best witnessed today at San Agustín at Isleta and San Ildefonso [Plate 16]. Unfortunately, other factors governed the selection of church sites within the pueblo so that the nave was not consistently oriented toward the south, which would have guaranteed continued light throughout the day, or the east, which would have secured light during the morning mass. Santo Domingo, for example, faces roughly west, while the sequence of Pecos churches actually reversed orientation in subsequent reconstructions.

The theatrical impact of the clerestory doubles when one enters the church after crossing a bright, sandy plaza, as the eyes require some minutes to accustom to the darkness. Then at the end of the nave is revealed the striking presence of light flung across the crucifix and altar, a radiance enhanced by the basic darkness of the interior.

Windows in the early churches were precious commodities, and Domínguez provided detailed descriptions of them in his report. But at that time windows were fewer than those seen in churches

1–26

San José

Las Trampas

The longitudinal profile of the church reveals the raised chancel roof necessary to create a transverse clerestory.

[1981]

1–27

San Agustín

Isleta pueblo

As a result of the 1960 renovation and the removal of the pitched roof,

the clerestory was restored to working order—a striking use of dramatic

illumination.

[1981]

1–28

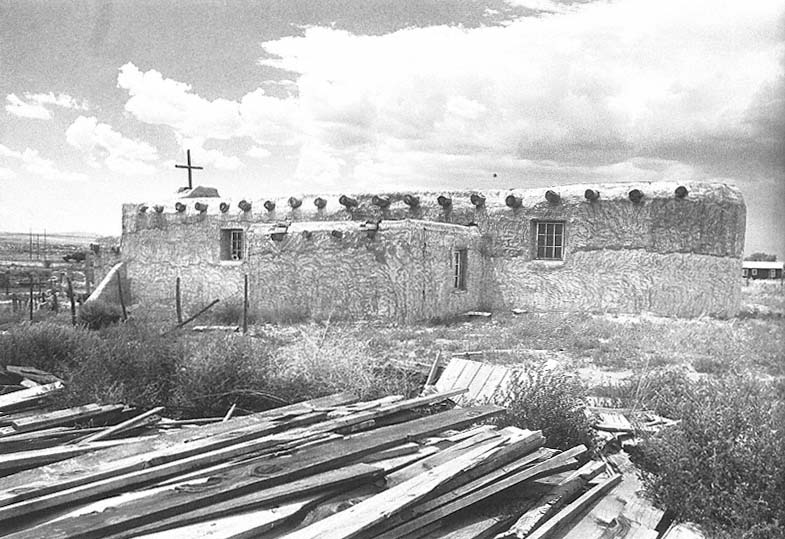

San Miguel

La Bajada

The single nave and battered apse are characteristic of the basic church.

[1984]

today and were almost certainly of smaller dimensions. Often restricted to a single side of the nave, such as the south at Acoma or the west at Isleta, these apertures high in the wall provided accents of light rather than a principal source of illumination—that role was granted to the transverse clerestory. Only with the large-scale importation of glass made possible by the railroads in the late nineteenth century could the size of windows be feasibly increased or new ones cut [Plate 13]. With their enlargement came a rather significant modification in the quality of light within the church. Even more severe was the effect of changes wrought by the pitched metal roof that accompanied American jurisdiction. While protecting the adobe walls from deterioration by water, the roof completely sealed off the clerestory, making the windows the sole source of light. Only at Santa Cruz, where a southfacing window lights the reredos (altarpiece) and altar, has a qualitative equal to the clerestory been found.