Walls

Upon the stone foundation, which rose about eighteen inches above the ground, the walls were laid, their progress checked vertically by plumb bob and horizontally by a wooden leveling device. A triangle of wood, this mason's level relied on a plumb to mark the midpoint of the horizontal stringer along the hypotenuse of the frame. An effective tool, easily replicable, the level could be used horizontally to check for true right angles as well as vertically to ensure that walls and doors were plumb. As the walls of the church rose, scaffolding was erected, sunk into the ground, lashed with rawhide, and fixed to the wall as necessary for stability.

Contrary to European practice, and much to the shock of the missionaries, the construction of walls was the women's province: "Among these nations," Benevides told us, "it is the custom for the women to build the walls and the men to spin and weave their mantas, and to go to war and the chase; if we try to oblige some man to build a wall, he runs away from it and the women laugh. And with this work of women there have been built more than fifty churches, with roofs, with very beautiful carvings and fretwork and the walls very well painted."[75] This practice probably derived from traditions in Pueblo prehistory, not surprising because real property—the house and its contents—belonged to the wife and was passed through matrilineal inheritance.

Without exception, New Mexican churches employed a type of construction known as bearing wall; that is, a structural system in which the roof was directly and continuously supported by the walls rather than by columns or piers arranged in series. Given the economic and technical conditions in which the churches were built, the width of the naves was relatively large and the weight of the roof substantial. Design was to some extent based on trial and rule of thumb, and walls tended to be massive. The resultant thick wall, whether of stone or adobe, imparted the particular character of architectural solidity to these religious structures.

One structural device notably absent in New Mexico was the arch, which one hundred fifty years later was to become a hallmark of California mission architecture. Few instances of the arch are known to have existed in New Mexico, the one remaining, although structurally impure, example being the arched opening in the chancel at Pecos. A lack of advanced building knowledge, dressed stone, and wood for the formwork used during construction precluded an architecture based on the vault or dome. The colony was restricted to churches using bearing walls spanned by heavy beams, an architectural method that traced back through Spanish history to Asia Minor and that by the end of the seventeenth century was somewhat archaic in central Mexico. Indeed, bearing wall construction also precluded the development of a church with side aisles, as the construction of columns or piers proved structurally impractical when built of adobe or unworked stone.

Stone construction methods drew on centuriesold Pueblo practices; in look and technique they possessed only a passing resemblance to all but the most elementary European masonry. Rock was used as it was found, neatly fissured into usable pieces in hillsides and exposed cuts; it was not finished in any way. (An eroded bank by the stream approaching Abo provides a clear example of the readily available sources for stone. So evenly are the stones fractured there that they give the appearance of having been quarried with tools.) Pieces commonly measured about one foot square and four inches thick. Normally laid up without mortar, stone fragments were sometimes inserted in the gaps to increase stability. In other instances an adobe mortar was packed around the stones; having no chemical binding power, this bond was noticeably weaker than the stones it joined.

Five of the major churches included in this book were constructed of stone: Quarai, built of a rich, red sandstone; Abo, quite similar in texture but not as intense in color; Gran Quivira, a gray-yellow limestone [Plate 5]; San José de Giusewa, a yellow limestone; and Acoma, actually a composite structure of stone and mud.

A masonry wall, deriving its strength from mass, was piled to nearly six feet in thickness (a rubble core filled with a more finished surface) to attain the height of fifty feet the early church builders sought. There was a pronounced battering to the walls, reducing their thickness as the walls rose and producing a section resembling an elongated version of a truncated pyramid. At Quarai the walls of the nave were considerably splayed in plan, adding some stability to the basic quadrilateral form, although its effect must have been minimal in comparison to the dead weight of the wall itself. In sum, these stone churches derived their structural capacity from the straightforward laying of stone on stone, which thickened the wall as required to allow it to reach the level of the roof beams.

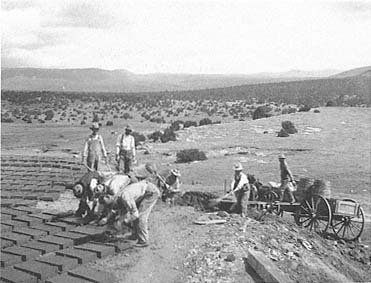

1–19

Making Adobe Bricks

during the reconstruction and stabilization of the Pecos churches,

circa 1915

[Museum of New Mexico]

Abo was one exception to this general pattern; there the thickness of the walls was reduced, and the walls were stiffened instead by buttresses—extra masses, like columns, attached or "engaged" to the walls themselves. This practice, which may have had its origins in the fortress churches of Spain, provided additional bearing surface just below the beams where the weight was concentrated, thereby helping transmit the load to the ground. At the crossing—the intersection of the nave and transepts—the wall was considerably thickened to accommodate the sizably increased load and to support the bell tower. In comparison to Quarai or Gran Quivira, Abo's walls were light and elegant, although hardly thin when compared with modern construction in wood or steel. Nevertheless, neighboring churches in the Salinas area avoided the risk the builders at Abo took when contriving its more sophisticated structural system.

The Spanish did not introduce mud construction into New Mexico; they merely rationalized its production. Although stone was a building material at Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon, it was used in conjunction with mud, which functioned as a mortar and finishing material. Exactly when the transition to a mostly mud or purely mud wall construction took place has not been ascertained, but the transference of the mesa top or cave villages to the river valleys made obvious the superseding of stone construction.

Continuing an attitude that perhaps derived from ceramic production, New Mexican builders did not use mud as a unit material, although blocks shaped like loaves of bread and called turtle backs were used to build the Casa Grande in Arizona.[76] The Indians built their pueblos on the basis of puddled construction: with or without a form, they piled up heaps of mud in layers to make walls. Piled up one or two feet at a time, walls were raised in a manner that paralleled the construction of pottery using rolled coils of clay. From a central point, these coils spiraled outward and upward and were ultimately smoothed over inside and out to remove traces of rough construction and lend unity to the surfaces. This technique enabled construction to proceed without formwork and with no time spent in the production of units. But extensive time was needed for each layer of the walls to season properly, drying slowly to retard cracking.

Mud bricks had existed in New Mexico prior to European contact, but their use was not widespread. The Spanish introduced the idea of unit construction in large numbers—in this case the manufacture of the basic mud brick and its use in a manner simi-

1–20

San Agustín

Isleta Pueblo

The problems created by applying hard plaster to

adobe walls are evident in the cracks and peeling paint.

[1981]

lar to stone. This common unfired mud brick was called adobe.

The word adobe derives from the Arabic atob , which suggests a Moorish, rather than a Spanish, origin.[77] Indeed, the earthen constructions of North Africa provided a centuries-old proving ground for this remarkably practical building system. Adobe is also related to the English daub, which formed one part of the wattle and daub construction of medieval England: applying (daubing) mud over a wooden framework.

Therefore, use of the word mud in this context is an oversimplification. Mud for adobe is not any form of wet earth; it is a carefully balanced product of clay, soil, and a binder such as straw, all blended in proper proportion. Although the straw does not increase the tensile properties of the brick, during drying it helps modulate evaporation in different parts of the block. Too much clay in the mix causes the bricks to shrink and crack while drying; too much sand causes them to become brittle and fall apart. An ideal composition is required, a balanced mixture derived in any locality only through a process of trial and error.

Wooden frames, with neither tops nor bottoms, form a number of bricks at a time. The mud is mixed in batches, and the form is filled while lying flat on the ground. A short time later, after the mud has set, the mold is lifted off, leaving a neat field of wet adobes each measuring roughly ten by fourteen by four inches. When the bricks are sufficiently dry, they are turned over and eventually stacked diagonally or on edge to complete the drying process. Unlike brick, adobe is not fired to high temperature in a kiln; being nonvitrified, the blocks are always susceptible to deterioration by moisture and wind. Traditionally, a layer of mud plaster applied over the adobe wall has been its primary means of protection against the elements. The absorption of moisture from the ground or the air or evaporation can cause a marked change in the size of the bricks, a movement that renders the use of the more stable cement plaster coatings impractical.

When the adobe matured, construction could begin. The builders laid up each course of blocks in an adobe mortar that rendered the construction homogeneous. Timbers imbedded horizontally within the wall at vertical intervals of up to four feet served to lessen cracking between bricks as the adobe or mortar dried or settled or could be used to reinforce the joint between new walls and old construction. After a few vertical feet of construction, the entirety was left to dry. Moisture permanently trapped in the walls could ultimately lead to the structural failure

1–21

The Architectonic Elements of the Church

[Source: Sketch by Robert Nestor, 1989]

of that section, or of the entire church, so judiciousness was the rule. Obviously this concern for moisture restricted construction to those periods of the year when rain was not a threat, a practice that compounded the extensive time periods required to build a church, often at least five to six years during the early periods. At difficult sites such as Acoma the construction activity extended over decades.

Adobe provides excellent bearing strength in compression and, in sufficient thickness, thermal mass [Plate 6]. The unbaked brick, however, is quite vulnerable to erosion by water and wind. During normal exposure certain portions of the external surface of a wall abrade, while other sections dissolve in rain, contributing to the subtly curving contour of an adobe structure. Wind erodes the top parapet, tapering the upper wall backward, while eroded earth is deposited at the base of the wall, giving it a pronounced bulge. Although in most cases walls are constructed as truly vertical or cleanly slanting, they acquire a sculptured profile that is never quite the same in any two places.

Erosion is both a natural and an unforgiving process, and church builders were forced to consider its effects when devising construction techniques. If the buildings are not replastered at regular intervals, weathering will eventually deteriorate the structural portions of adobe walls. One problem is known as coving. As water drains off the wall, or pours from the drains, it splashes on the ground and decays the base of the wall. Poor drainage compounds the effects of the problem, although a stone foundation can lessen it. Unless the water sources are checked, however, the wall will become seriously undermined, or coved, which can ultimately lead to the collapse of the structure.

The parapet remained another chronic problem area. Because this section of the wall extends past the roof level, it is exposed to weathering on three surfaces and is thus three times as susceptible to erosion. In many instances the parapet is the first part of the wall to deteriorate, furthering pronounced dissipation on the tops of the walls, destroying the roof and beams, and eventually leading to ruin. Perhaps in no other method of construction is the adage that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure so true. And even though there have been many attempts to eliminate the required upkeep, such as a pitched roof to cover the tops of walls, bricks or concrete blocks used for the parapets (now a common practice), a hybrid adobe made of mud mixed with cement or oil, and the more usual—although technically unsuccessful—application of cement stucco, nothing is as technologically and aesthetically triumphant as the time-consuming application of mud plaster [Plate 14]. (See Ranchos de Taos for a discussion of stucco plastering and a restoration story with a happy ending.)

The walls of stone or adobe were plastered on both inside and outside to appear monolithic and to suggest the more finished wall surfaces of the advanced religious architecture of Mexico or Spain. On the exterior the mud plaster served not only to integrate the separate bricks (because a chemical bond was formed) but also to add an inch or more of protective surface as a first line of defense against the elements. At Quarai and Jemez Springs traces of plastering and even painted decoration were discovered during excavation, indicating that the perceived surface was ultimately the architectural concern and that the vehicle of construction, stone or mud brick, was only the means to that end.

Building and plastering the walls of the church were women's work performed during the initial construction and then every second year for maintenance. As in ceramic production, the final coat of mud plaster was smoothed or burnished with sheepskin, deerskin, or small, round stones.[78] The technique was most often employed when interiors were plastered with yeso (or yesso ), a baked gypsum mixed with wheat flour and water to form a thick paste. Yeso walls were typical of Moorish interiors and created a surface much harder and more durable than mud, but this technique was less widespread than coating a wall with whitewash.[79]