Pecos Pueblo:

Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles de Porciúncula

1598?; after 1629; c. 1696; c. 1717

In 1838 the last dejected inhabitants of Pecos pueblo left their homeland forever. This remnant of a once-thriving community sought asylum with their linguistically related kin at Jemez. As a last act of devotion they deposited the sacred image of San Antonio that had graced the wall of their church with the European town nearby, instructing the new caretakers to maintain the image with appropriate care and dignity. (Each year a festival would renew the contract between the Pecos survivors and their patron saint.) So closed a long and full chapter in the history of New Mexico Indian and Hispanic relations.

A rare exception to the hundreds of miles of arid plains lying east of the Rio Grande was the Pecos River drainage. As the last outpost, the hinge between settlement and desolation, the river had supported habitation in the form of a series of Indian pueblos and later European settlements. The largest among them was the thriving Pecos cluster, which at the time of the Spanish contact was estimated at a population of about two thousand souls. During the Archaic Period (from 5500 B.C . to A.D . 700–800) the settlement was characterized by a small population living in pit houses but already engaged in agriculture.[1] After the year 900, however, no record remains of inhabitation for the next two to four centuries. Typically the architecture developed from partially subterranean to fully aboveground structures, first built in a puddled mud technique but by 1300 constructed almost entirely of sandstone from the vicinity. All the villages except Cicuye were abandoned by 1450, its population concentrated in structures stacked up to five stories in height.[2]

The village's position on the edge of Pueblo culture guaranteed an intermediary role to Pecos, in which they traded cotton stuffs, pottery, belts, and food for buffalo products, beads, and leatherwork. In time the Pecos Indians also served as the intermediary between the Plains Indians and the Spanish, as did Taos to the north and Gran Quivira to the south. As usual, the recorded story begins with Coronado's party, which moving eastward in search of riches reached Pecos in May 1540. The Spanish camped there in late April or early May on their way east to the "country of the cows" (buffalo).[3]

Coronado's chronicler, Pedro de Casteñeda, noted the configuration of the pueblo: "Cicuye is a pueblo of nearly 500 warriors, who are feared throughout the country. It is square, situated with a large court or yard in the middle containing the estufas. The houses are all alike, four stories high. . . . The village is enclosed by a low wall of stone."[4] The setting was superb: a low ridge within the valley allowed

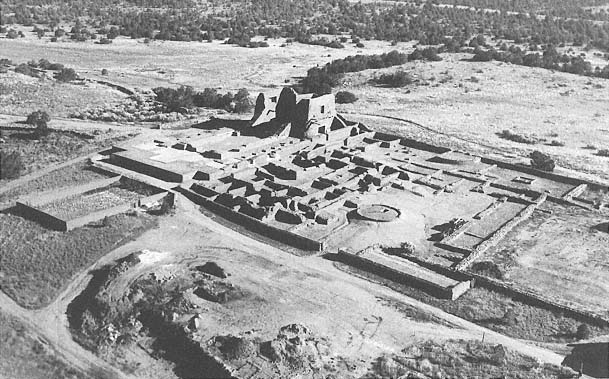

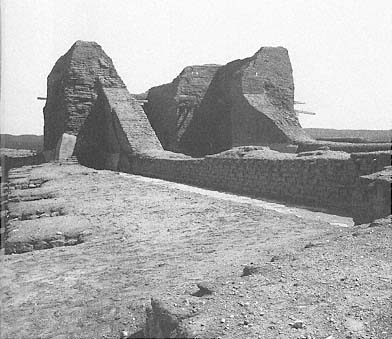

17–1

Pecos

Mission and pueblo ruins from the southwest.

[Fred Mang, Jr., National Park Service, no date]

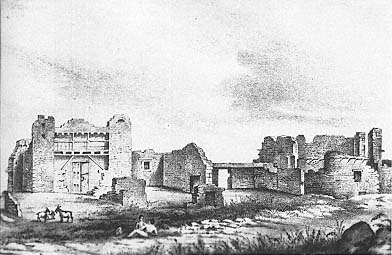

17–2

Pecos Pueblo

Restoration of the Pecos settlement about 1700 by

S. P. Moorhead. The mission and convento are in the

upper left.

[Courtesy of the R. S. Peabody Museum]

a clear view of the surrounding land. A spring within the pueblo's walls provided the water, as did a second spring to the east and Glorieta Creek.[5] The Pecos River helped irrigate the crops, including the cotton used for weaving. On January 1, 1591, Gaspar Castaño de Sosa, in full battle dress, took Pecos and noted in his Memoria that the village possessed sufficient firewood and building timber to allow each family to build more or less at will.[6]

Pecos was established in 1598 as the headquarters of the eastern division, and a church was built.[7] Kessell noted that "if even the structure was used, it must have been only briefly." It was built about a thousand feet northeast of the pueblo and measured twenty feet by thirty feet; it was built of stone, plastered inside and out, and faced south. Given the limited space available for construction on the narrow mesilla, there was no convento.[8] The threat of an Indian uprising forced the friar to leave, and the church was subsequently razed. Only in 1616 were friars once again dispatched to the pueblo.

During that year a Franciscan was assigned once again to Pecos, and a sanctuary, Nuestra Señora de los Angeles (Our Lady of the Angels), was constructed or rebuilt. Although the structure might have been scanty, with the priest still living somewhere within the south part of the pueblo itself, a dedication took place on August 2, 1617 or 1618, the feast day of the patron saint.[9] The second church arose on a site two hundred feet south of the pueblo structure, attempting to minimize its vulnerability to potential raiders. Fray Pedro de Ortega is credited with initiating the works, and by the early 1620s enough of a convento had been completed to provide him with lodging.

The uneven site required considerable fill to level its floor, similar to those problems at San Ysidro at Gran Quivira or San José de Giusewa at Jemez Springs. Its foundations, however, lay on solid bedrock. Construction continued during the jurisdiction of Fray Andrés Juárez, although how much he accomplished has been difficult to ascertain. Juárez, who had entered New Mexico in 1612 and had stayed at Santo Domingo before his assignment to Pecos, wrote to the viceroy on October 2, 1622, that

a temple is being built in this pueblo de los Pecos de Nuestra Señora de los Angeles because it has no place to say Mass except for a jacal in which not half of the people will fit, there being two thousand souls or a few less. And then, God willing, it will be finished with his help next year. Therefore I beg Your Excellency, for the love of our Lord, please order that an altarpiece featuring the Blessed Virgin of the Angels, advocate of the pueblo, be given, as well as a Child Jesus to place above the chapel which was built for that purpose.[10]

He continued with comments on trade between Spanish and Indian groups, noting that "many times when they come they will enter the church and when they see there the retablo and the rest there is, the Lord will enlighten them so that they want to be baptised and converted to Our Holy Catholic Faith. And in all the good that results from the altarpiece Your Excellency will share."[11] Clearly the intention behind construction of a significant edifice was not only to glorify the Lord but also to serve as a propaganda device for the divine work.

Although the claim to a church large enough to hold the whole pueblo of nearly 2,000 could have included the use of an atrio, this second church still commanded respect.[12] Benavides, visiting the territory from 1625 to 1629 to inspect the missions and encourage their development, termed Nuestra Señora de los Angeles de Porciúncula "a convent and church of peculiar construction and beauty, very spacious."[13] Alden Hayes recorded its dimensions as 133 feet long by 40 feet wide at the east entrance, about 45 feet high (almost two times the height of what is seen today), with walls up to 10 feet thick.[14] Agustín de Vetancurt called it a "magnificent temple . . . adorned with six towers, three on each side," with walls so thick "services were held in their recesses."[15] The quality of its woodwork—Pecos was noted for its fine Indian carpenters—matched the scale of the enterprise. A two-storied convento abutted the church to the west, the priest dwelling in the upper story. As the seventeenth century came to a close the mission at Pecos stood firmly established, with its structure a physical statement of the presence and importance of the church.

If Indian-religious relations appeared to be relatively stable, those between the civil authorities and the church remained volatile. Colonists usually came to New Mexico with the intention to gain. "The governor had to buy his position and neither he nor his men were paid by the Crown."[16] Obviously this prompted exploitation—either of the land or its inhabitants—to extract financial reward. Under the jurisdiction of governors like Luis de Rosas (governed 1637–1641), the situation became intolerable. Rosas was a harsh man, demanding quantities of blankets from the Pueblos and forcing Christian pueblos to work with the detested Apache and Ute under intolerable conditions. He traded knives for buffalo hides and meat with the Apache and engaged in a campaign of exploration and lucrative commerce.[17] Although an extreme example, his term of office was indicative of the typical pat-

tern, which forced the missionary to act at times as a powerless intermediary. This pattern did little to aid evangelical efforts among the Indians. Yet an inventory, probably of 1641, stated that the mission "has a very good church, provision for public worship, organ, and choir. There are 1,189 souls under its administration."[18]

As was the case in most of the missions, the Pueblo Rebellion of 1680 brought the first chapter of its history to a close and inaugurated the second. The insurrectionists ignited piles of juniper and piñon, setting the roof of the church afire. The clerestory now served as a chimney vent, sucking in air and expelling ashes out the door.[19] Walls were pulled down, and the facade tumbled into the nave, covering the ashes of the pyre. The work of more than six decades lay buried by adobe.

With the Reconquest, plans were made to reestablish the missionary presence at Pecos and to restore or rebuild the fallen structure. Within a year Vargas turned his attention to these matters and wrote the viceroy, although his primary interests were military and strategic as well as evangelical. "At the pueblo of the Pecos, a distance of eight leagues from Santa Fe, 50 families could be settled, because it too [like Taos] is an Apache frontier and, being so surrounded by very mountainous country, suffers unavoidable ambush. Settled in this manner, and backed by the military of the villa, it will prevent the robberies and murder that follow from assured entry. It is very fertile land which responds with great abundance to all kinds of crops planted."[20] By the following year a (rebuilt) church stood on the site, but curiously it was reconstructed adjacent to the nave of the earlier structure. Utilizing the remnants of the north wall of the old convento but reversing the orientation, it measured about twenty feet by sixty to seventy feet. The structure was hastily built under the direction of Fray Diego de Zeinos, who stayed about a year at the pueblo but was ultimately removed to ease tension after accidentally shooting an Indian.[21]

Vargas visited the site in the fall of 1694 and was assured that the pueblo "would build their church in order that divine worship might be celebrated in greater decency than at present. They have provided for the construction of a chapel which they provided by showing me the beams for to roof it. . . . They had rebuilt for [the reverend] its very ample and decent convento and residence."[22] Improvements continued as part of the process of use and construction. Vargas recorded in November 1696 that they had "added to the body of the church by increasing the height of the clear story [sic ], and to the sanctuary by adding two steps to the main altar, and had walled in the sacristy and had closed the portion at the entrance to the convento with a wall."[23] Even though the walls and roof were improved periodically, the process of deterioration by the elements subverted efforts to maintain the church.

By 1705 Fray José de Arranegui had undertaken the building of a new structure, although he continued to use the makeshift chapel built on the ruins of the prerebellion church. In 1706 Fray Juan Álvarez reported that construction was under way.[24] Kessell cautioned, however, that Alvarez made a similar claim for fifteen other pueblos including Acoma, where the pre-1680 church still stood, and he may actually have been noting substantial repairs rather than truly new construction.[25] This was to be the fourth and last church at Pecos pueblo, three times the size of the Zeinos structure but not as large as the Juárez sanctuary. Thus, the last effort fit within the walls of the second church, although it maintained its reversed orientation to the west. Two bell towers flanked the main door and formed a shallow narthex. A clerestory illuminated the nave, augmented by one window high on the north wall and three facing south overlooking the convento. Construction was probably complete by 1787. The old convento was still habitable and retained more or less the same form, although probably with a nominal degree of repairs and upgrading. The raggedly profiled mound of red adobe that one sees today is primarily the ruin of this church.

The remainder of the Pecos ecclesiastical story is one of dissolution and decay. Although the pueblo occupies an excellent site within the valley, its vulnerability to Apache attack increased as the population declined. In 1694 there were 736 inhabitants, but smallpox epidemics in 1738 and 1748 reduced the population to one-fourth of that figure. Yet there were still moments of glory among those of depression, moments of pride within the confines of the vows of poverty. Fray Juan Miguel Menchero recorded in 1744 that "the construction was done through the industry and care of the Father of the mission without having spent even a half-real of His Majesty's funds." The church, he said, was "beautiful and capacious."[26]

Bishop Tamarón visited the church, but he left no specific comments or criticism; he was, however, troubled by the problems in communications between clergy and congregation. "Here the failure of the Indians to confess except at the point of death is more noticeable, because they do not know the Spanish language and the missionaries do not know those of the Indians." Perhaps this was by choice.

17–3

Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles, Plan of the Seventeenth-Century Church and Convento

[Source: Hayes, The Four Churches ]

17–4

Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles, Plan of the Eighteenth-Century Church and Convento

[Source: Hayes, The Four Churches ]

17–5

Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles, Hypothetical Restoration of the Eighteenth-Century Church and Convento

[Lawrence Ormsby]

17–6

Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles

The massive ruins of the eighteenth-century church fit within the

crenellated footprint of the towers that buttressed its predecessor, the

post–Pueblo Revolt structure.

[1981]

17–7

Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles

Lithographic view of the mission ruin in 1846.

[From Calvin, Lieutenant Emory Reports ]

"In trade and temporal business where profit is involved, the Indians and Spaniards of New Mexico understand one another completely. In such matters they are knowing and avaricious. This does not extend to the spiritual realm, with regard to which they display great tepidity and indifference."[27]

At the time of the 1776 Domínguez visit both the newer structure and the remains of the older one still stood.

As we enter the [newer] church, on our right under the choir is the entrance to an old church outside the wall. The old building extends to the south, with the door where I said, and is joined to the convent on the Epistle side. And in order not to become involved, I state now that it is a size to fit in the nave of the one we are describing and that it is falling down. As we enter this old church, outside its wall on the left is the sacristy now in use, and the baptistry now in use is on the right, also outside the walls, and the entrance to both rooms is from the old building.[28]

Domínguez found at least two aspects of the complex worthy of comment: "All the beams in the roof are well wrought and corbeled," and the "two beautiful stables, each with a straw loft that was a part of the convento structure."[29]

De Morfi's 1782 description testified to the continuing demise of the community:

In 1707 it had about 1,000 souls. In 1744, 125 families, in 1765, 178 . . . families, with 344 persons. Today 84 inhabit it. It suffered such a considerable decline, being the frontier for enemies who with pretext of peace frequented it and took the opportunity to wreak havoc.

It has a capacious and beautiful church and a convent where two religions lived previously; today there is only one.[30]

The pueblo continued its downward spiral. Disease and raids took their respective tolls, and there was little chance of reversing the process of dissolution. After 1782 Pecos suffered the reduced status of a visita of Santa Fe and, in 1820, of San Miguel del Bado.[31] At the turn of the century "land-poor" Spanish settlers were admitted to the pueblo lands, and the independence of the village as an entity was completely undermined. By 1820 the imbalance was already apparent: the census listed 58 Pecos Indians and 735 Spanish settlers. The last entry in the church's book was recorded in 1829. Nine years later the remaining 17 to 20 Pecos Indians left for Jemez, with the Hispanic settlers agreeing to celebrate the Feast of Nuestra Señora de los Angeles each August 2.[32] This, then, was the final end of the village that Benavides had noted "of Jemez nation and languages . . . 2,000 Indians and a very fine mission."[33]

17–8

Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles

Excavation and stabilization of the church ruins in December 1940.

[W. J. Mead, Museum of New Mexico]

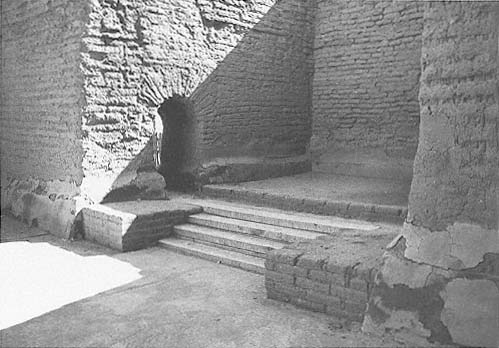

17–9

Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles

The chancel of the eighteenth-century church with an adobe arch, a rare building element in

New Mexico.

[1981]

Pecos today is an impressive monument, even in pieces [Plate 6]. On the narrow mesilla are the ruins of the pueblo itself, excavated by Alfred Vincent Kidder from 1915 to 1925 in the summers; these excavations figured prominently in the formulation of southwestern archaeology. Kidder believed the cellular configuration of the structure, clustered around a plaza, to be indicative of a preconceived plan built for defense. The southern group remains unexcavated but is visible as a mound between the church and the visitor center.

Today the remains of both the postrebellion church and the final, fourth church are discernible. Of the two, the younger structure is the more dominant. The western part of its construction is completely eroded, although the considerable bulk of the apse end remains. Constructed of adobe stacked to a thickness of almost six feet, the nave is articulated into two shallow transepts and steps up into the chancel, which once contained the altar. Behind the altar in the north wall is one of the rare remaining instances of the arch in New Mexico.

Like its predecessor, the fourth church boasted two towers and a balcony spanning the entrance. The structure lasted well into the nineteenth century. Emory made a record of Pecos in 1847 on his expedition for the U.S. Army, and at that time the church, although deteriorated, still bore vestiges of its earlier form. Like Domínguez, Emory was impressed by the woodwork.

Here burned, until within seven years, the eternal fires of Montezuma, and the remains of the architecture exhibit, in a prominent manner, the engraftment of the Catholic Church upon the ancient religion of the country. At the end of the short spur forming the terminus of the promontory are the remains of the "estuffa", with all parts distinct, at the other are the remains of the Catholic church, both showing the distinctive marks and emblems of the two religions. The fires from the "estuffa" burned and sent their incense through the same altars from which was preached the doctrine of Christ. Two religions so utterly different in theory, are here, as in all Mexico, blended in harmonious practice until about a century since, when the town was sacked by a band of Indians. . . .

The remains of the modern church with its crosses, its cells, its dark mysterious corners and niches, differ but little from those of the present day in New Mexico. The architecture of the Indian portion of the ruins presents peculiarities worthy of notice.

Both are constructed of the same materials; the walls of sun-dried brick, the rafters of well-hewn timber, which could never have been hewn by the miserable little axes now used by the Mexicans, which resemble, in shape and size, the wedges used by our farmers for splitting rails. The cornices and drops of the architecture in the modern church are elaborately carved with a knife.[34]

Two diagonal braces reinforced the balcony span, eliminating the need for central columns like those seen in early photographs of Cochiti and Zuñi. But the abandoned structure suffered under the forces of nature and the neighbors.

Hewett reported that as late as 1858 the roof still remained in place.[35] A widowed Mrs. Kozlowski told Adolph Bandelier that her husband had removed the timbers and used them to build or roof structures (outhouses) on his property. Bandelier visited the site in 1880 and wrote of it, "The ruins first strike his [the tourist's] view: the red walls of the church stand boldly out on the barren mesilla , and to the north of it there are two low brown ridges, the remnants of the Indian houses."[36]

In 1915 a significant chapter in New World archaeology was inaugurated with the beginning of excavation at Pecos by Alfred Vincent Kidder, who was followed by Jesse L. Nusbaum of the Museum of New Mexico. The site was registered as a state monument in 1935, and in 1965 it was elevated to National Monument status, administered by the National Park Service. The area of the monument was further increased in the 1970s with the donation of additional land.[37] A new interpretive center was added early in the 1980s.

The imposing red mass of the church dominates the site and the valley—an earthen lump that can be seen from miles away. Visiting the site, one will see not only the church and convento ruins and the pueblo structure but also the stabilized foundations of the second church, easily ascertained by its dentilated profile—the foundation of the "six towers" cited by Vetancurt. On the narrow mesilla at Pecos, one derives a clear picture not only of the sequencing of the four structures that occupied the land over a period of two centuries, but also of the relationship of the church to the pueblo. At first the church was separate from the pueblo; later, perhaps for defense, the church was closer or even abutting the village; but it was always a distinct entity that relied primarily on the topography of the ridge for its sense of connection.