Las Trampas:

San José de Gracia de Las Trampas

c. 1760

In the original license that authorized the construction of a church and chapel at Las Trampas, Bishop Tamarón admonished the parishioners to construct a religious edifice that would be appropriate and proper. "We charge the citizens of the place to try to maintain the aforesaid chapel with all possible seemliness and cleanliness so that the devotion of the faithful may thus be aroused to frequent it and the spiritual consolation which is the aim of our pastoral zeal."[1] Although the church has suffered its share of vicissitudes in its two hundred years of existence, that charge has been met.

Driving the mountain road from Santa Fe through Santa Cruz to Taos, one comes upon the church of San José de Gracia de las Trampas as an unexpected oasis. The village that surrounds it has changed with time and reflects modern building practice and a more contemporary lifestyle. But the church itself, recently restored, reflects and illustrates a devotion and a construction that in many places have long passed. To this day the church is maintained by its parishioners, and the possession of the key and the care of its interior rotate periodically within the congregation.

The vegetation changes abruptly as the plateau gives way to the Truchas peaks of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. From the scrub juniper and piñon that dot the plains there is a marked shift to the evergreen forests that blanket the slopes. Flat land becomes a premium and water and sun a concern.

Mountain villages such as Las Trampas were settled near those few flat areas available for cultivation that could be served by irrigation. Valuable water from rivers and streams and south-facing slopes seemed to have been the primary considerations. The fields, although limited in dimension, did yield sufficient crops, including, somewhat surprisingly, fruits such as apricots and peaches.

In 1712 Sebastián Martín received a land grant for a large area including that of Las Trampas. In 1751 twelve families seeking a new place to live and farm were granted about forty-six thousand acres by Governor Tomás Vélez Cachupín, which included 180 varas of farmland for each family. In addition, plots for fifty-seven residences and dwellings were included, as was a series of one-half-vara units set aside for "droppings, enclosures, stables and other objects of that nature."[2] If this area proved insufficient, there were also 1,620 varas that could be transferred to the twelve families from the original grant. The exact fertility and conditions of the soil were undoubtedly known quantities, and this last piece was to forestall any difficulties in settling land disputes, if that proved necessary.

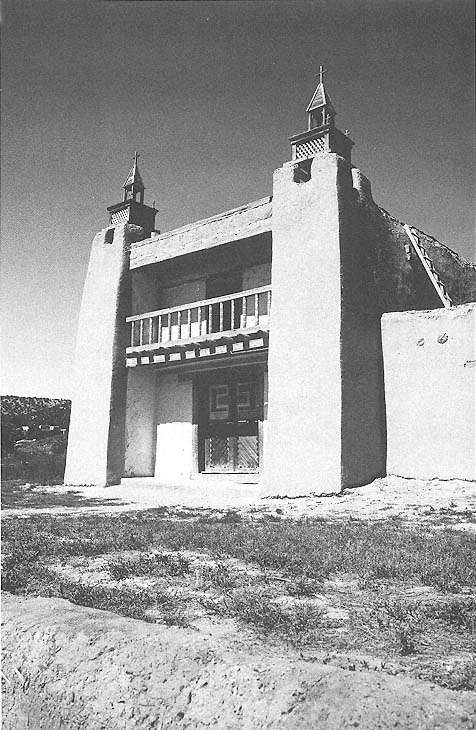

13–1

San José

San José possesses the most poised facade of the New Mexican churches, a composition

pitting the strong verticals of the towers against the lighter wooden balcony.

[1984]

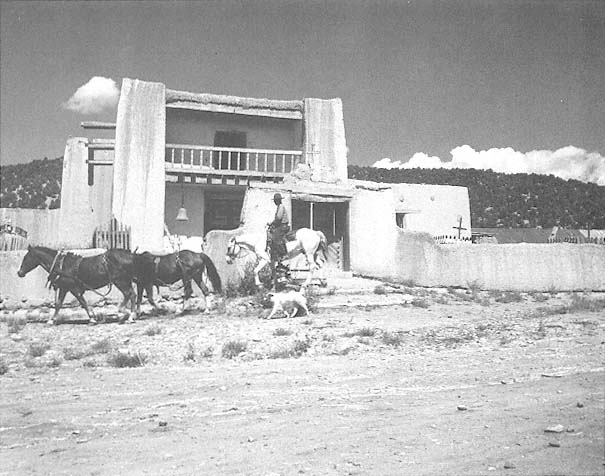

13–2

Las Trampas

The remnants of the original fortified plaza are barely discernible in this photo.

[Dick Kent, 1984]

Living conditions were not secure in the area, however. The mountains were distant from the plateau areas protected by the Santa Fe garrison, and as a result the settlers lived uneasily. A missionary resided at Picuris pueblo, but he could offer none of the physical security provided by military forces. Consequently, the town was formed as a fortified plaza in the manner of Chimayo and Ranchos de Taos and distinct from the dispersed ranchos of the southern Rio Grande area. Whether the plaza was ever completely encircled, however, has not been ascertained.

The settlers' spiritual needs were equal to their secular wants. With the "Indian question" far from settled and the seemingly short distance of two leagues between Las Trampas and Picuris rendered dangerous, the citizens petitioned for their own church. In 1760 Bishop Tamarón made a visitation of the New Mexican churches and responded favorably to the petition for a church. On June 15, 1760, at Picuris pueblo he granted permission to construct a "chapel and church with the title and avocation of Lord St. Joseph of Grace and of Most Holy Mary Immaculate," charging the builders to make it "seemly, clean and otherwise required."[3] Given the small number of families that made up the congregation, there would be no resident priest. Instead, the church would be treated as a visita of Picuris.

By 1776, when Domínguez made his visit, the population had grown to sixty-three families with a total of 178 people. The church, following Tamarón's direction, was built within the walled enclosure of the plaza and did not measure more than thirty varas. Domínguez seemed impressed with the nascent settlement and wrote of its setting, "It runs from southeast to northwest, with a small river with a rapid current of good crystalline water in the middle. It is not half a league long, but since it is rather wide, it has fairly good farmlands on both banks of the river. Watered by this river they yield quite reasonable crops with the exception of chile and frijol." He also told of its history: "The chapel has been built by alms from the whole kingdom, for the citizens of this place have begged throughout it. The chief promoter in this has been one Juan Argüello who is more than eighty years old."[4]

The chapel at the time was almost complete. The Franciscan noted that the choir loft still lacked a rail and that the twin towers flanking the entrance were hardly begun. This note leads one to conclude that the church was first built as a typical cross-shaped box with a flat facade, the towers added later for aesthetic and symbolic reasons rather than out

13–3

San José, Plan

[Sources: Kubler, The Religious Architecture , 1940 based on

HABS; and field observation, 1986]

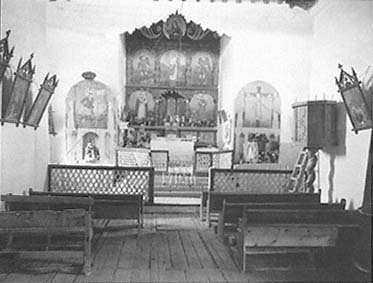

13–4

San José

circa 1935

The interior with its full complement of santos.

[T. Harmon Parkhurst, Museum of New Mexico]

of structural necessity. And yet today it is just these towers and the dignity of the facade that form the gateway to the church and its ranking as the finest of the Spanish colonial religious buildings.

Following the customary pattern of building in Spanish settlements, the church was constructed with transepts. In addition, the sacristy at the Epistle (right) side filled out its profile. Windows were present by the time of Domínguez's report: he stated that there was one window on either transept end, plus two on the Epistle side near the nave. Widened over the course of time, their position has probably been the same, although the dimensions have varied from the originals.

The altar was raised by four steps fronted by wooden beams in the usual manner. Originally the floor throughout was packed earth, although today only the baptistry is so made. The wooden floor in the remainder of the church is a late-nineteenth-century addition at the earliest because milled lumber became available in the mountain villages only sometime after the American occupation.

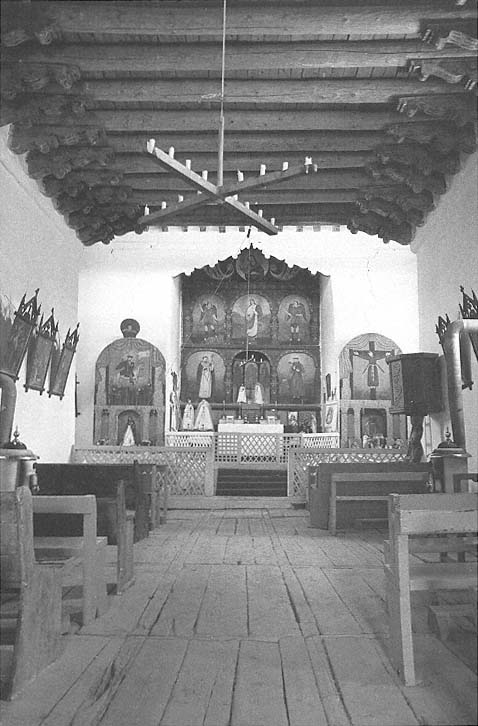

Fortunately San José is not covered by the tin shed roofs that now protect many of the abode churches, and as a result the light quality from the windows—however enlarged—and the clerestory reveal an interior characterized by softness and repose. The wash of light over the white plastered walls and the soft rendering of the prismatic masses create a spatial impression that complements the cubic forms of the exterior towers. The altar area is narrower than the nave, which, coupled with a decorative cut-wooden screen, distinguishes the sanctuary. The altar, now of wood, as in many of the churches, was originally of adobe, so that its base literally grew out of the earth.

Over the entry to the church and extending as a balcony on the exterior is the choir loft, with access only by ladder [Plate 8]. Its floor is also of packed earth. The baptistry is a simple rectangular room connected to the nave and found to the right immediately upon entering. Domínguez noted that the baptismal font consists of "an adobe pillar in the middle [of the room] but no font." The sacristy, which extends the southwest transept, has a simple roof with corner fireplace. Domínguez had little to say of its worthiness: "A very ordinary room without a key."[5]

At the time of the friar's visit there was little by way of religious furnishing within the church. If the building was still under construction, this would not have been too surprising. There was a "middlesized image in the round of Lord St. Joseph" and some paper prints, but little else. Today the setting is

13–5

San José

San José offers a classic Spanish Colonial church interior. Five reredoses fill the nave, the

principal altarpiece illuminated by the characteristic transverse clerestory.

[1981]

quite different: there are five major reredoses, with a number of subsidiary images; all are of high quality and interest. Two flank the nave, while the remaining three—including the principal reredos—complete the sanctuary. The frames of the reredoses date from somewhere between 1776 and 1871, according to Louise Harris, and are attributed to José de Gracia Gonzáles.[6] They were probably painted in Sonora and brought by trade caravan to Las Trampas. Harris noted that they were a bit "too good" to be of New Mexican origin and not good enough to be from central Mexico—hence the attribution to Sonora.

Not all visitors have been as kindly in the evaluation of the church and its art as was Fray Domínguez. John Bourke, who visited Las Trampas on July 19, 1881, reflected the Anglo view of Hispanic Catholic iconography (a view that seemed to have been shared by Bishop Lamy). Bourke wrote, "Upon one wall hung a small drum to summon the faithful to their devotions. The paintings were of wood and were I disposed to be sarcastic I would remark that they ought to be burned up with the hideous dolls of saints to be seen in one of the niches of the transept." But his scathing condemnation is followed by a more temperate, although still condescending, attempt at accurate description:

This criticism, in all justice, would be apt and appropriate in our own day; but we should not forget that this little chapel dates back to a period and condition of affairs when the Arts were in their infancy, so far as these people were concerned; when the difficulties of transportation compelled the priests to rely upon native talent alone. This talent supplied the fearful artistic abortions we laugh at today; yet these pictures and dolls served their purpose in object-lessons to a people unable or unwilling to comprehend abstract theology—and altho' a newer and more progressive day has dawned, one which can readily replace these productions with the works of artistic merit, the halo of antiquity has endeared these smoke blackened daubs to the simple-minded youths and maidens who gather here to recite the Rosary or chant the Creed. To the traveller, the greatest charm of New Mexico will be lost when these relics of a by-gone day shall be superseded by brighter and better pictures framed in the cheap gilding of our own time.[7]

San José has been the subject of two major restorations, one easily accomplished and the second the scene of a major social confrontation. The first took place in 1932 under the auspices of the Committee for the Preservation and Restoration of New Mexico Mission Churches. At the time the bases of the towers were repaired, new beams for the balcony were mounted, and a new turned balustrade for the

13–6

San José

circa 1910?

Early in this century only one wooden turret remained, the clerestory

structure was sagging, and the tops of the walls had been stripped of

plaster by the elements.

[Museum of New Mexico]

13–7

San José

1949

The fragile wooden turrets have disappeared and the entry arch has deteriorated since their invention and

installation.

[New Mexico Tourism and Travel Division]

13–8

San José

In a 1960s rehabilitation, the turrets were remade and the church walls

were stabilized. The baptistry adjoins the nave.

[1986]

balcony was installed—until that time the railing had been lattice. During the period of the restorations the building was measured and recorded by the HABS, which documented several New Mexican churches during the Depression.

In the 1960s the town and the church were threatened—or blessed, depending on point of view—with the promise of a widened road. Seen as progress by many of the citizens—connections with Taos and Santa Fe had been tenuous because of poor road conditions—the widening of the road would have removed part of the churchyard, thereby causing, in the eyes of the preservationists, irrevocable damage. Among the leaders of the battle for the church was architect Nathaniel Owings, who later wrote of the saga in New Mexico Magazine . Apparently the townsfolk were not united in their stand to save the church. Although venerated, the building was old, and the increased benefits of better communication could not be disparaged. Owings recounted, "The villagers' attitude was summed up by the comment of one that, if their church as a historic monument was standing in the way of progress as indicated by the building of the road, they would blow up the church."[8]

Undaunted, although no doubt discouraged, the preservationists were able to secure National Landmark status for the church in April 1967, which granted them leverage and badly needed bargaining time. In the end a compromise was struck: the so-called Treaty of Santa Fe, dated June 8, 1967.[9] An alternate road design was instituted; the church was not only saved but was also repaired. The walls were mud plastered; there was new roofing, the first since the 1932 restoration; and cupolas of wood for the two towers were executed to a design by John Gaw Meem based on old photographs.

Las Trampas today is the high point of the scenic tour from Santa Cruz to Taos. The apse of Ranchos de Taos, justly celebrated and publicized in the paintings of Georgia O'Keeffe, might be better known, and Santa Cruz might be larger, but neither possesses the softness and quiet dignity of San José de Gracia. The surrounding architecture reflects modern incursions, and the architectural definition of the plaza has seriously deteriorated, but the form and the feel of the eighteenth-century original can still be discerned. San José de Gracia de las Trampas, because of its handsome proportions, the wealth of its art, its maintenance, and its refinement in spite of crude materials and technology, remains the finest of the Spanish colonial church interiors.

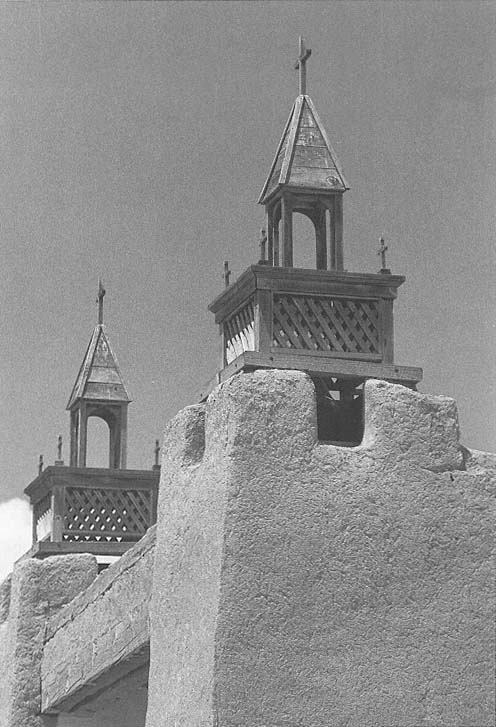

13–9

San José

The ornate wooden finials, designed by John Gaw Meem based on historic prototypes, were

installed at the time of the last major restoration.

[1981]