The Cathedral of Saint Francis

1869–1895; 1966; 1986

Architects: Antoine and Projectus Molny; François Mallet

When the location of the provincial capital at San Gabriel proved to be impractical, it was moved south to Santa Fe, where it has remained since its establishment in 1610. The city complied only roughly with the ordinances for founding new cities. These regulations dictated that the "principal church" was not to occupy the central position on the plaza mayor, which was reserved for the most important civil structures of authority. The plaza was to be the center of the municipality and would be augmented by "smaller plazas of good proportion . . . where the temples associated with the principal church, the parish churches, and the monasteries can be built." More specifically, "the temple [principal church] shall not be placed on the square but at a distance and shall be separated from any other nearby buildings, or from adjoining buildings, and ought to be seen from all sides so that it can be decorated better, thus acquiring more authority."[1] "Decoration" was a long time coming to the church in Santa Fe, and in spite of the ordinances, the Parroquia was tucked on the southeast corner of the plaza.

Like the city itself, the church—today the cathedral—still occupies the same site, although the location of the church itself has shifted slightly over the years. The identification of the original structures is made more difficult by the construction of commercial structures in the nineteenth century, which eradicated the entire eastern half of the plaza. The Parroquia as such no longer exists: the building was subsumed by the stone cathedral, substantially completed in the 1880s, that succeeded it.[2]

The parish church was not the first major religious structure in the capital. That honor fell to the chapel of San Miguel across the Santa Fe River in the Barrio Analco (see San Miguel). An appropriate parish church was a necessity, however.

According to Kubler, a rudimentary chapel existed on the site of the Parroquia as early as 1610 and was probably the product of Fray Alonso de Peinado's first efforts.[3] It possessed neither commodity nor architectural quality and was later referred to by Benavides as a mere plastered pole structure (jacal).[4] Appreciated or not, this original church was dedicated to Nuestra Señora de la Asunción (Our Lady of the Assumption).

By 1626, when Benavides took office, or by 1630, when his first report was published, about two hundred fifty Spaniards lived in the city and roughly three times that many Indians were affiliated with them, most of them serving in menial positions. The town was lacking a suitable parish church, Benavides related, "as their first one had col-

3–1

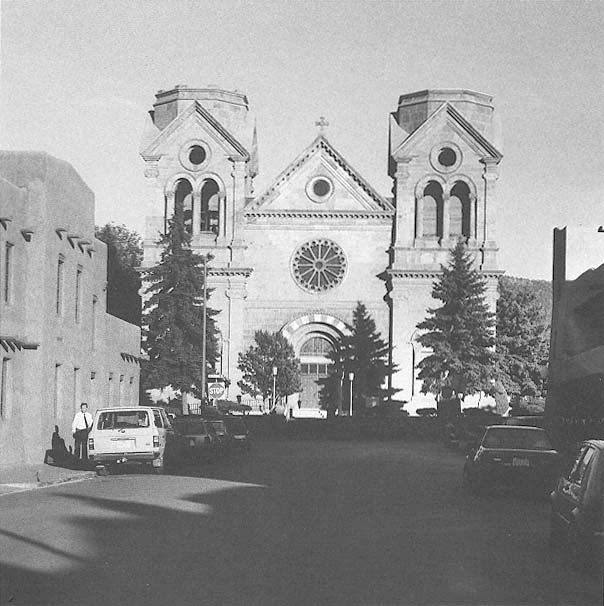

Cathedral of Saint Francis

The spireless principal (south) facade, based on a design by Antoine and Projectus Molny, executed in a style

recalling the Romanesque religious structures of their native France.

[1986]

lapsed. . . . I built a very fine church for them, at which they, their wives and children, personally aided me considerably by carrying the materials and helping to build the walls with their own hands, to the honor and glory of God," and not incidentally to the glory of the friar himself.[5] The institution seemed to progress satisfactorily: "We have them well instructed, and they set a good example. The most important Spanish women pride themselves on coming to sweep the church and wash the altar linen, caring for it with great neatness, cleanliness, and devotion, and very often they come to partake of the holy sacraments."[6]

While the second parroquia was under construction, San Miguel served as the parish church. Chavez believed that construction of the convento might have preceded or progressed more rapidly than the church itself because the convento was probably in use by 1631. Construction of the church was completed by 1639. The dedication of the church possibly changed, as in 1661 there were references to a church of the immaculate conception.[7] Fronting the church and extending westward toward the plaza was the cemetery. The convento lay south of the nave, which was oriented east-west. A report from the 1640s recorded that the capital of the territory was also the seat of the custodia and that it had "a very good church in which is kept the Blessed Sacrament; everything pertaining to public worship is very complete and well arranged; it has a fair convento, and there are 200 Indians under its administration who are capable of receiving the sacraments."[8]

Unlike nearby San Miguel, the Parroquia was destroyed during the Pueblo Revolt, and although Vargas vowed to rebuild the ruined structure in 1693, he in fact never did. What remained of the pre-1680 structure was rebuilt as the existing Conquistadora chapel and was refurbished to house the statue of the Virgin that had accompanied the Vargas expedition of Reconquest (see El Rosario). The population of the city had grown, increasing pressure for the erection of a religious edifice of more appropriate stature. The convento for the Franciscans, however, had been maintained through the auspices of Governor Cubero, who took office in 1697. Within fifty days of his arrival, repair work was "for the most part" completed.[9]

A chapel in the east torreón of the Palace of the Governors still stood at the time of the Vargas entry into Santa Fe. During the years of native occupation the chapel had been converted to serve as a kiva. Necessity seems to have triumphed over desecration, as the chapel was reconsecrated and served as a center of worship until the construction of the

3–2

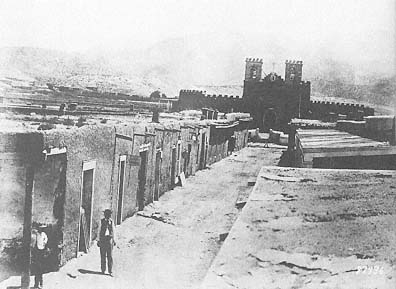

Looking North on San Francisco Street

Circa 1878

The Parroquia stands at the end of the street.

[U.S. Signal Corps, Museum of New Mexico]

new parroquia almost two decades later.[10]

The new church, shifted on its original site, was under construction in 1713, as evidenced by two documents referring to building activity. One, dated 1713, referred to "the church which is now being built in Santa Fe"; the second described a house "on the main street which goes from the Plaza to the new church now being built."[11] The structure was probably completed by 1717, and from then until the end of the eighteenth century, the building suffered continual decay. Tamarón noted its existence in his report of 1760 but had little to say either in praise or condemnation: "On May 25 [1760], which was Whitsunday, the visitation was made with all possible solemnity in the principal church, which serves as the parish church. It is large, with a spacious nave and a transept adorned by altar and altarscreens."[12] Tamarón appeared more caught up with the excitement of building the chapel of Nuestra Señora de la Luz (Our Lady of the Light) on the south side of the plaza.

"Surely when one hears or reads Villa of Santa Fe, along with the particulars that it is the capital of the kingdom, the seat of political and military government with a royal presidio, and other details that have come before one's eyes in the perusal of the foregoing," wrote Domínguez in 1776, "such a vivid and forceful notion or idea must be suggested in the imagination that reasons will seize upon it to form judgments and opinions that it must at least be fairly presentable, if not good." Alas, the city did not live up to those expectations. In all, he had little that was positive to say about the villa other than to remark its splendid site: "Its appearance, design, arrangement, and plan do not correspond to its status as a villa nor to the very beautiful plain on which it lies, for it is like a rough stone set in fine metal."[13]

The Parroquia, in his estimation, fared a little better. He noted that it was built of adobe, that its doors faced west, and that its "regular transept" was raised three steps up from the rest of the nave. He gave no hint that the walls of the church converged slightly toward the transept. "Across the mouth of the nave a clerestory rises to light the transept and the sanctuary," while three windows in the south wall lit the nave. "The church has a choir loft in the usual place which occupies the full width and projects 5 varas into the nave. . . . The entrance is below it near a corner, like a trap door, reached by a ladder inside the church. Its furniture, or adornment, is the entire absence of any, for there is not even a bench for the singers. The floor is bare earth packed down like mud."[14] The effort of making the building registered favorably on the visitor, perhaps more than the actual structure. He conscientiously recorded what was there: the cemetery, the floor of wooden planks, the governor's throne in the transept, and the wooden altar screen. In addition to the two altars in the chancel, four more flanked the nave, two on either side. The beams in the ceiling were new, suggesting a recent renovation. The baptistry stood to the right, adjacent to the convento to the south, and was entered under the choir. Protecting the image of the Conquistadora, the Rosario chapel extended the north transept and was built in the typical manner, although it lacked a clerestory. Domínguez's judgment was mild: "Its interior may not be cheerful, but it is not gloomy either."[15] Whereas the Benavides church may have borne only a plain facade, the eighteenth-century church featured two tower buttresses spanned by a balcony from which "all the view the villa has to offer to the north, south, and west can be easily surveyed."[16]

Before 1797 portions of the church had dangerously deteriorated and had subsequently been rebuilt. The inevitable processes of entropy and erosion were only temporarily halted, however, as the church was again in ruinous condition or had even collapsed by 1799.

In 1804, by which time the walls had been substantially completed, disaster called: just before the roof beams were scheduled to be installed, the church was struck by lightning and the new construction was destroyed. The sponsorship of the rebuilding is credited to Don Antonio José Ortiz, who also funded improvements to San Miguel about the same time.

After it [the parish church in this city] had fallen down, six years ago, I undertook by myself to reconstruct the same, and in fact I [prepared it] for the vigas last year. [O]wing to the damage of lightning which struck, I was obliged to tear it down again and enlarge it ten varas. From the foundation up I extended it 8 varas and reconstructed its walls and have it now ready nearly up to the placing of the vigas, there missing four rows of adobes in order to be able to roof it.[17]

Ortiz paid to lengthen the church toward the west and to erect a chapel dedicated to San José that extended the south transept. The church thus filled out a cross-shaped plan configuration, while the Conquistadora chapel and chancel were recast into the characteristic battered form.[18] Renewed efforts completed the structure in 1808.

The church form at that time displayed certain properties still observable in the earliest photographs of the Parroquia since it was described in a report by Agustín Fernández, vicar general of the

3–3

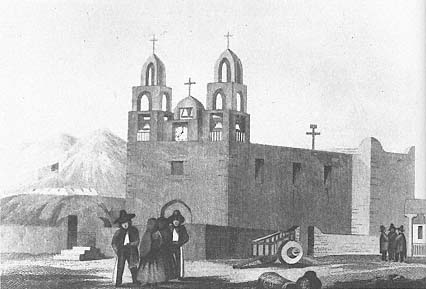

La Parroquia

The church in 1846 as sketched by J. W. Abert.

[Museum of New Mexico]

3–4

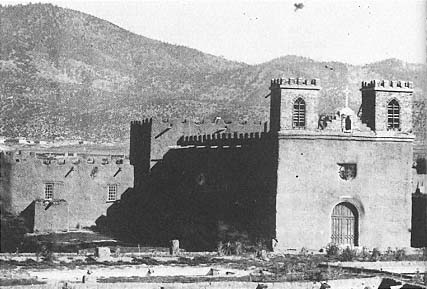

La Parroquia

circa 1867

Within a decade of Lamy's arrival in New Mexico, the Parroquia was polished with

a mild Gothic trim.

[Nicholas Brown, Museum of New Mexico]

archdiocese of Durango, as having two small towers and measuring about 29 feet by 162 feet—a relatively long and narrow space.[19] The elongation of the nave in subsequent rebuildings reduced the dimensions of the campo santo, thereby bringing the facade closer to the plaza.

When the Americans entered the city in 1846, they found the church, made of adobe, little changed in architectural style from the previous century. Typically, the mass of the church and the manner of the pious stood foremost in the eyes of observer Lieutenant J. W. Abert.

October 4, 1846. We were early awakened with the ringing of the campanetas, summoning the good citizens of Santa Fe to morning mass at the parroquia, or parish church. I had a great desire to see the interior of this church, which with the "Capilla de los Soldados," are said to be the two oldest churches in the place, and were doubtless those alluded to by Pike, when he says, "there are two churches, the magnificence of whose steeples form a striking contrast to the miserable appearance of the houses." . . . The body of the building is long and narrow; the roof lofty; the ground plan of the form of a cross. Near the altar were two wax [wooden] figures the size of life, representing hooded friars, with shaved heads, except a crown of short hair that encircled the head like a wreath. One was dressed in blue and the other in white; their garments long and flowing, with knotted girdles around the waist. The wall back of the altar was covered with innumerable mirrors, oil paintings, and bright colored tapestry. From a high window a flood of crimson light, tinged by the curtain it passed through, poured down upon the altar. The incense smoke curled about in the rays, and, in graceful curves ascending, lent much beauty to the group around the priests, who were all habited in rich garments. There were many wax tapers burning, and wild music, from unseen musicians, fell pleasantly upon the ear, and was frequently mingled with the sound of the tinkling bell. . . .

In the evening [of October 5] I made a sketch of the parroquia, although mud walls are not generally remarkable; still, the great size of the building, compared with those around, produces an imposing effect.[20]

Like Abert, Lieutenant William Hemsley Emory was taken by the activity more than the space:

August 30. This was on a Sunday.

Today we went to church in great state. The governor's seat, a large, well-stuffed chair, covered with crimson, was occupied by the commanding officer. The church was crowded with an attentive audience of men and women, but not a word was uttered from the pulpit by the priest, who kept his back to the congregation the whole time, repeating prayers and

3–5

La Parroquia

1880

In this illustration by Charles Graham, probably based on a

photograph by Ben Wittick, a wooden arch distinguishes the

central nave from the sanctuary.

[Museum of New Mexico]

3–6

Cathedral of Saint Francis

1880

Taking advantage of some clever planning strategy on the part of the

architects, the builders used the roof of the Parroquia as a work platform

for the new stone structure rising around it.

[Museum of New Mexico]

incantations. The band, the identical one used at the fandango, and strumming the same tunes, played without intermission. Except the governor's seat and one row of benches, there were no seats in the church.

The interior of the church was decorated with some fifty crosses, a great number of the most miserable paintings and wax figures, and looking glasses trimmed with pieces of tinsel.[21]

Five years later when Jean-Baptiste Lamy arrived in New Mexico, he set to putting his house in order. Although he might have harbored no love of the native architecture, aesthetics was not the major issue. "The trouble with the native tradition as Bishop Jean-Baptiste Lamy and his French priests saw it was that New Mexican Catholicism of the times too closely resembled its crumbling churches," wrote Bruce Ellis in a recent monograph on the cathedral.[22] As a cathedral, rather than a parish church, the building demanded a greater expression: "No adobe-walled, viga-spanned structure could be as high or as wide as proper cathedral dignity required; to permit its consecration in strict accordance with canon law the building must be of solid masonry throughout."[23] Yet another factor was the chronic repair demanded by adobe construction: why not build a masonry structure that required less maintenance? Nor was there popular support for the existing structure on the basis of its historical significance—such appreciation would have to wait another century to flourish. For the moment modernity and progress held sway over sentiment. "When finished," a newspaper editor wrote in 1873, "the edifice will be a credit and an ornament to the city and territory. . . . That old mud church [the Parroquia] has stood for years looming up dingy, gloomy, and awkward, like an adobe brick-kiln—an eyesore to every man of taste and a disgrace to the city."[24]

After saving and repairing the Castrense chapel, Lamy sold it in 1859 to raise money for the Parroquia and to acquire a piece of land upon which to erect a school. But he also had bigger plans in mind, and they had little to do with traditional Spanish colonial building types. The parroquia had become his cathedral, and the bishop sought a church building that would objectify the church's newly elevated status. Neither adobe nor local builders could produce what he envisioned, and for stylistic expression he looked, not to the land around him or its parent country of Spain, but back to his mother country of France.

Lamy's search had numerous precedents in the history of ecclesiastical architecture. Early in the

1840s Greek and Roman revivals had been used to reinvigorate the spirit of the American republic, however farfetched and muddled the stylistic associations were. Among the Catholic and Episcopal faiths Gothicism became the predominant religious architectural style, mostly through the original instigation of A. W. N. Pugin, who looked back to the medieval era in Europe as the most fervent—and truest—expression of Christian religion. The impact of medievalism was felt as far afield as New Mexico, where many of the simple adobe churches received at least minor Gothic redressing. Early photos of the Parroquia show that it, too, was modified under this influence, with crenellations added to the parapets and pointed arches to the belfries.

It was not the Gothic style, but the Romanesque, in which the cathedral of Santa Fe was finally built. Lamy came from southern France, where the Romanesque churches of the eleventh and twelfth centuries remained the major monuments—the Gothic cathedrals were mostly built farther north in the Isle-de-France or further east. In spite of years of living and working abroad, even in the relative wilderness of Kentucky, Lamy retained his early stylistic preferences. But the Frenchman encountered problems in realizing his vision: lack of a building tradition that used the vault and the arch was one; lack of money was another. The new bishop overcame them both. He imported the architects Antoine and Projectus Molny from France as well as certain craftsmen who worked with local crews. Molny probably prepared his drawings while still in France and sent them to Santa Fe "in or just before 1860."[25]

As in any project of this size, complications arose. At the start the work was given to an American contractor who either was "dishonest" or "did not understand the work."[26] In 1869 work commenced; the cornerstone was laid on October 10—and stolen within a week! "Some heathen with infamous hands tore up the cornerstone of the new cathedral which had been laid by Bishop Lamy only the Sabbath preceding . . . and everything of any value, silver and gold coins, etc., etc., were [sic ] carried off."[27]

The strategy for erecting the new cathedral was rather ingenious. Because the Parroquia would be in use during the period of construction, the new structure would be built over and around it. The width of the existing church would determine the width of the central nave, which would be flanked on either side by an aisle. The roof of the Parroquia would serve as a useful platform for the construction of the vaults of the masonry structure.

A red native stone was chosen for the walls and a

3–7

Cathedral of Saint Francis

An engraving of the revisions proposed by Francois

Mallet to the Molny scheme, including completion of

the spires left as stubs.

[From Aztlan , by William G. Ritch, 1885; Museum of

New Mexico]

3–8

Cathedral of Saint Francis, Plan

[Sources: Architects' drawings by McHugh Loyd Associates; and field observations,

1990]

volcanic tufa for the ceiling, which established a prototype for succeeding religious architecture in New Mexico—although few, if any, builders followed it. Modifications were made en route: the width of the proposed facade was reduced and rotated slightly to align it with the streets. Work stopped for about four years beginning in 1874, and a new architect, François Mallet—French, living in San Francisco—replaced Antoine Molny, who had returned, blind, to France in 1874. Mallet prepared documents and an estimate for completing construction, including the two spires that were never built.[28] When the centering for the vaults was removed, cracks appeared, prompting the insertion of triple arches between the pillars.[29] The arrival of the railroad facilitated the movement of some materials, although stone was still transported to Santa Fe from Lamy by teams. European workmen arrived in 1883, lending their stone-carving skills to the project.[30] A year later construction had reached a point sufficient to permit the final demise of the adobe Parroquia, its earth used to fill the streets of the city: "Its adobes and rocks are now doing other public work," said Father James Defouri.[31]

In time the cathedral rose, with its new stone walls surrounding the venerable adobe church it was to supersede in majesty and style. John Bourke, writing in 1881, observed the construction process and its results:

I went to the Cathedral of San Francisco, a grand edifice of cut stone, not more than half completed and enclosing within its walls the old church of adobe. As I purpose, at a late date, giving a more detailed account of this old building and others equally venerable in Santa Fe, as well as a sketch of the town itself, I will content myself now with saying that the town has been transformed by the trick of some magic wand during the past 12 years. . . .

The old church in itself is a study of great interest; it is cruciform in shape, with walls of adobe, bent slightly out of the perpendicular. Along these walls, at regular intervals, are arranged rows of candles in tin sconces with tin reflectors. The roof is sustained by bare beams, resting upon quaint corbells. The stuccoing and plaster work of the interior evince a barbaric taste, but have much in them worthy of admiration. The ceilings are blocked out in square panels tinted in green, while two of the walls are laid off in pink and two in light brown. The pictures are, with scarcely an exception, tawdry in execution, loud colors predominating, no doubt with good effect upon the minds of the Indians. The stucco and fresco work back of the main altar includes a number of figures of life size, of saints I could not identify and of Our Lady. In one place, a picture of the Madonna and Child represents them both with gaudy

3–9

Cathedral of Saint Francis

The unusual configuration of arches and columns

reflects revisions made to ensure structural stability.

[1981]

crowns of gold and red velvet. The vestments of Archbishop Lamy and the attendant priests were gorgeous fabrics of golden damask.[32]

By 1886 the church was substantially completed, but a construction hiatus in 1895 left the eastern end of the church in adobe until 1966. Structural and economic problems continued to haunt the structure. During the 1930s cracks again appeared in the vaults and north wall, belying the problematic soil of the old burial ground and the poorly laid foundations. With John Gaw Meem as consultant, the foundations were reinforced in an attempt to stabilize the settlement.[33]

What was left after the removal of the Parroquia was a competent Neo-Romanesque church with two side aisles, round arches, a great rose window, and the stubs of two eighty-five-foot towers that would never receive their spires. At the time it must have appeared as a very impressive structure unlike anything ever seen in the territory. Today it is a handsome church with little of particular aesthetic note. If there is a lesson to the venture, it might be that a provincial version of an international style is often of less interest and emotion than a superb example of a local tradition. Nevertheless, the traditional style was unable to produce a structure of a cathedral's desired scale and magnificence. A recent renovation, executed in 1966–1967, demolished the remaining adobe structures except for the Conquistadora chapel and introduced a south chapel dedicated to the blessed sacrament that also serves daily as the entrance to the cathedral.[34] A grand skylight floods the altar with light. In the mid-1980s renovations designed by McHugh Lloyd and Associates, Santa Fe, were again in progress, flooring the crossing and the sanctuary in a pattern of light and dark wood.

Recent revisions in ecclesiastical doctrine resulting from the Vatican II accord have brought about the modification of many traditional church interiors, and this last renovation is one such project. Liturgy will always determine church architecture; the process is inevitable. Unfortunately, the new lighting lacks the orchestration characteristic of traditional church architecture. The ambient nature of the cathedral's light has reduced the light quality from a source of inspiration or wonder to a source of illumination. The miniature Conquistadora chapel, however, remains the cathedral's north transept and retains the character of its predecessors, a reminder of the humble beginnings of the city and its "principal church."

3–10

Cathedral of Saint Francis

circa 1948

The church during services.

[Robert H. Martin, Museum of New Mexico]

3–11

Cathedral of Saint Francis

The altar area was opened during the renovations begun in 1986. Although the sanctuary is

bathed in light, the unorchestrated quality of the illumination is foreign to the choreographed

play of lighting in the traditional New Mexican church.

[1986]