New Trends in Nepali Poetry

This chapter presents some Nepali poetry that reflects the predominant trends of the past twenty years or so. I have resisted attaching the label contemporary to this poetry, partly because it is difficult to decide a specific date from which contemporary literature should be deemed to have commenced and partly because all literature is by its very nature contemporary when it is written. Qualities such as "modernity," "contempor-aneity," and so on can be assessed only subjectively, and assessments change with the passage of time. Of course, this fact has not prevented most Nepali critics from debating ceaselessly about what is, and what is not, modern.

The majority of these poems are drawn from an anthology entitled Samsamayik Sajha Kavita (Contemporary Sajha Poetry) published in 1983 as a supplement to the important Sajha Kavita anthology of 1967. Because the youngest poet to appear in this latter volume was Banira Girl (born in 1946), it was originally supposed by the publishers that the new anthology would be restricted to works by poets born after this date. The editor of Samsamayik Sajha Kavita , Taranath Sharma, argued that this was not an appropriate criterion for selection. Many poets born before 1946 began to write rather later in life. He also pointed out that poets who were included in the earlier volume, such as Mohan Koirala and Ìshwar Ballabh, could not be regarded as uncontemporary because their poetry had continued to evolve. In an interesting postscript to the anthology, Sharma described the features of the Nepali poetry he considered to be truly contemporary.

After about 1965, Nepali poetry entered a period during which its accessibility and popularity seriously declined. The new class of intellectuals wrote in language that was pedantic and abstruse and made

references to mythologies and concepts that were alien to ordinary Nepalis. The old school continued to publish verse in time-honored metrical forms that imparted traditional values. Thus, the new poetry became innovatory and experimental to the extent that it was incomprehensible to all but a small intellectual elite, whereas the old style of poetry re-worked well-worn themes and formulas, offering little that was new.

Both of these styles retain some currency today, and the poems by Ìshwar Ballabh and Avinash Shreshtha demonstrate that abstraction is alive and well. This style of poetry has been eclipsed in more recent years by a new and most welcome development. The distinctive features of the most recent poetry are linguistic simplicity, the complete absence of metrical forms, the use of symbols drawn from everyday life, and frequent references to present-day social and political issues. It therefore exhibits more than anything else the influence of Nepali poets such as Rimal and Sherchan and is deserving of the title contemporary poetry in the sense that it is clearly intended to speak to its times.

During the early 1970s, and to some extent during the previous decade, too, most modern poetry was pessimistic and gloomy and gave evidence of a growing sense of social alienation among the educated urban young. Such tendencies are clearly apparent in the poems of Bhairava Aryal and Haribhakta Katuval. In 1979, however, changing political circumstances brought about some significant new developments in Nepali poetry.

Since 1960, Nepal had been governed by a pyramidal system of Panchayat councils at local and national levels, headed by the monarch. Although all political parties were banned, dissatisfaction with the political status quo became increasingly apparent and eventually led to the national referendum of 1980. During the twelve months leading to this referendum, strenuous efforts to influence public opinion were made by both supporters and opponents of the Panchayat system. In the capital, a new atmosphere of political freedom produced the sadak kavita kranti (street poetry revolution). Young poets recited their poems on street corners, and people gathered on New Road each evening to purchase collections of political verse all supporting the alternative "multiparty" option. These collections were printed and sold in large numbers and were typified by the short-lived journal Swatantrata (Freedom). The August 1979 issue of Swatantrata , a "Street Poetry Revolution Special," included political poems by young writers such as Ashesh Malls., Bimal Nibha, and Min Bahadur Bishta, who are now among the leading exponents of the "new" poetry. Nepali poetry had once again descended from its ivory tower to become a medium for the expression of popular sentiment. As a consequence, its language regained its former simplicity,

and its references and allegories were readily comprehensible. Although these poets' aspirations were not fulfilled by the outcome of the referendum, the legacy of this brief but important period is still clearly apparent in more recent poetry.

As this book goes to press in July 1990, conditions in Nepal are changing once more. The Panchayat system has been dismantled, Nepal's constitution is being redrafted, and political parties are operating freely. One hopes that all of these changes will produce an atmosphere that is more conducive to free expression than has been the case hitherto and that Nepali literature will thrive as a result.

The selection of poems that follows is arranged as far as possible in an order that reflects the process of change. Dates of first publication are given, when known. Ìshwar Ballabh and Avinash Shreshtha are both important present-day poets, but the ways in which their poems contrast with the rest of this selection should perhaps serve as a warning to those of us who seek to identify simple and consistent patterns in the process of literary and cultural change.

Bhairava Aryal (1936-1976)

Bhairava Aryal was well known for his humorous and satirical essays, which have been published in four volumes. He was also a poet of some importance. "A Leaf in a Storm" (Huriko Patkar ) expresses a sense of alienation and pessimism that was common in the Nepali poetry of the late 1960s and early 1970s, and this poem may shed some light on the aspect of Aryal's character that contributed to his suicide in 1976.

A Leaf in a Storm (Huriko Patkar)

He frightens himself, defeats himself,

this consumptive man, this man of today,

this man who is called Man.

Every night when he goes to sleep,

he puts his death warrant under his bed,

every day as he rises at dawn

he winds on a heavy turban of rags.

Yes, through each day I walk,

selling my moments, selling my days,

as if to bargain for a night with my wife,

for some nights with life and the world.

These are this century's terms:

from Creation I must rent each day,

to buy myself I must sell myself here.

My days transport the paralyzed sun

in a cranky ambulance,

1 stand at the junction of listless eyes,

amazed and astonished:

my day comes empty-handed without gifts,

my day goes back gloomy without news.

(c. 1966; from Sajha Kavita 1967)

Haribhakta Katuval (1935-1980)

Katuval was born in the northeast Indian state of Assam in 1935 and was also known by the pseudonym Pravasi , "exile." He was one of the most popular Indian Nepali poets, and unusually for an India-based Nepali writer, he was also well known in Kathmandu. His poems describe the meaninglessness and futility of modern life, a common theme in the Nepali poetry of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Katuval died in 1980.

Haribhakta Katuval's poems and songs are collected in Samjhana (Remembrance, 1959), Bhitri Manche Bolna Khojcha (The Inner Man Tries to Speak, 1961), Sudha (Nectar, 1964), Yo Jindagi Khai Ke Jindagi ! (This Life, What Life Is This? 1972), and Badnam Mera Yi Ankhaharu (Infamous These Eyes of Mine, 1987).

A Wish (Rahar)

Father, I will not go to school,

there they teach the history of days long dead.

Math's formulas are old,

the rusted components of a machine,

I refuse to live in history's pages,

I must live in days still to come,

I must overtake history, become something more.

So father, I will not go to school,

there they teach the history of days long dead.

I prefer ideals I can feel

to ideals which are locked in a frame,

I prefer building my road as I travel

to walking a ready-made road,

my muscular arms need a hoe, not a tome,

and plans are not for me.

My feet must traverse each lofty peak

to pay off the debt of this earth.

Father, I will not go to school,

there they teach the history of days long dead.

(no date; from Katuval 1972)

This Life, What Life is This? (Yo Jindagi Khai Ke Jindagi?)

This life, what life is this?

Hollow within, alive from without,

sucked by the atomic dread,

harassed by the spirits of problems,

this life, what life is this?

Here you must sleep with your head on a gun,

here you must live on the edge of a knife,

afraid to open or close your eyes:

this life, what life is this?

Like a bangle made of glass

adorning a trader's showcase,

it can break at once on a maiden's wrist.

Like cheap sandals made of rubber,

it can suddenly break as you walk.

This life might suddenly break:

this life, what life is this?

(no date; from Katuval 1972)

Ìshwar Ballabh (B. 1937)

Ìshwar Ballabh was one of the trio of writers who initiated the Tesro Ayam movement from Darjeeling in the early 1960s. Unlike Bairagi Kainla, however, Ìshwar Ballabh continues to publish poems today. Many of these are apparently intended to do little more than to convey a series of abstracted images, and in a poem such as "The Shadows of Superfluous Songs" (Anavashyak Gitka Chayaharu ) language often seems to be an end in itself. Thus, the legacy of the dimensionalists is clearly apparent in many of Ìshwar Ballabh's works. In others, however, there is evidence of a concern with the realities of human society. "Where Is the Voice?" (Avaj Kaham Cha? ) is the expression of an overtly humanistic poet who is contemptuous of the hold religious tradition still has on the ordinary people of Nepal.

Ìshwar Ballabh's poems are collected in Agoka Phulharu Hun, Agoka Phulharu Hoinan (These Are Flowers of Fire, These Are Not Flowers of Fire, 1972), Samantara (Parallels, 1981), and Kasmai Devaya (Oath of the Gods, 1985).

The Shadows of Superfluous Songs (Anavashyak Gitka Chayaharu)

All of a sudden I sit down to write

the lines of songs which no one needs;

I always attempt such pointless sorcery,

feeling perhaps they will vanish within me,

running away like water,

their forms turning dark and vague.

Once I would say, "Do not make me write songs,

my songs are all lost, they make my flesh ache,"

but I was afraid when I heard someone say,

"No song is lost"—so I write.

This is a thousand-year process, my love,

my songs are formed and they vanish,

disappearing into dark backgrounds,

like my skylines, my countless dreams.

"Be not a mirage," said I, and I heard,

"This is a path which must go on."

"Remembering the endless," I say, then I hear,

"Continue it must, like these strange voices"

—and then a song is made.

Sometimes I suddenly try to be

like the juniper trees which no one needs,

like these tall mountain peaks:

I have found them standing like evening,

ruminating in solitude,

I have touched them deepening like the sky.

I am surprised—why is the evening not faith?

Why is it not the flowers

offered up in temples?

So I refuse to write more songs

for which there is no need,

the far shores are not illusions, my love,

"They are illusions which nobody needs."

Climbing stairs which must be climbed,

I am up on Olympus, the pagan god's peak,

far below I see waters and shores;

my desires a river seen from a mountain,

my strange urges a city seen from a mountain,

the communal life of strangers:

a bond of chance seen from a mountain;

the lines of my song are those images,

for as long as they may last,

these forms always busy with shadows,

these distances, too, are my kin,

desolate places always busy with light.

I am asked, "What is this shadow?"

It is the superfluous songs I write.

(no date; from Ballabh 1981)

Where is the Voice? (Avaj Kaham Cha?)

We had watched the festival of flowers,

we had seen them in their rows,

even as we spoke another folktale formed;

tales of Sunkeshari and Dikpal disappear,

Dikpal is lost, of the demons there's no sign[1] in the festival of flowers.

Unfamiliar faces are walking by

with paper flowers for the Gai Jatra,[2] their lines are dark smoke, dark words,

they walk with dark conduct.

I asked—where is this procession going?

but received no reply:

we always want an answer,

but no procession ever gave one.

We asked, what are these eyes and masks?

Just their festival, they replied.

Just a procession that has not set out,

just lines all ready which have not moved.

Those shapes and horizons,

those skies and patterns!

How distant it is, unreachable,

however far the procession goes,

tramping mountain paths,

up hill and down dale, however long we walked,

that unreachable world was nowhere,

nowhere to be found.

Why can't we arrive there today?

With our feast of flowers

we have made flowers grow in the gardens.

Here one must not mention it;

it could be a song,

[1] Princess Sunkeshari and Prince Dikpal are the central characters of one of the most popular Nepali folktales. Dikpal rescued the princess from the clutches of some demons (daitya ) who had devoured all the inhabitants of her father's kingdom and kept her under a spell.

[2] This is the annual "cow festival" celebrated by the Newars of the Kathmandu Valley.

it could be a god,

it could even be this Kal Bhairava.

To the dumb Kal Bhairava by the Hanuman Gate[3] we said, get up and walk,

why do you squat on a rock?

But he did not walk; he is afraid,

he would melt if he walked the roads of Man.

We are quite different:

he is the Bhairava, we are men:

such valorous men, defeated by a stone Bhairava.

Multilingual men defeated by a Tantric rock:

the history of this day.

Come, you rocks,

soften and melt and run:

this is the world of Man.

Whoever tells a story here

just watches a flower blooming;

a few pretty blossoms, and Man melts away.

Come, oh dreams, tell the tale of Dikpal,

sing the song Sunkeshari sang.

The sky and the earth have died without songs,

the rocks are dead,

they have hardened, hardened,

even God has died and turned to stone;

flow now, rocks, come and save

the thing we once called life.

But far away there was nothing,

no breeze, no sky, not even those houses.

Apprehensive, we watch the god of faith,

we watch Ganesh and Bhairava,

we watch even the stairs.

At such a time,

why does no voice reassure us?

Where is the voice?

Where is the voice?

(1981; from Ballabh 1985)

Hem Hamal (B. 1941)

Hem Hamal is a popular modern poet who writes gently satirical poems in simple, musical language. His work is typical of a recent trend of "softness" in Nepali poetry, which is also evident in the poems of Mohan Himanshu Thapa (b. 1936) and Shailendra Sakar (b. 1946).

[3] Kal Bhairava is a famous statue of the fearsome aspect of Shiva situated near the Hanuman Dhoka entrance to the old royal palace in central Kathmandu.

Village and Town (Sahar Ra Gaum)

If the town prospers

the country progresses,

so say the men of the town.

If it rains this year

the village will prosper,

so say the village men.

A man from the town

stops his car on the road

and asks, "How are the crops

in the village this year?"

A farmer comes forward to answer:

"The farming is not so bad,

but can the sweat of our labors

fill your motor cat's stomach?"

(no date; from Samsamayik Sajha Kavita 1983)

Children Going to School (Pathshala Jana Lageka Naniharu)

Do not ask these little children,

coming toward you all in a line,

do not ask them where they are going.

They have their own roads to travel,

their own tools for creating themselves.

They have feet you cannot see,

do not ask about when and where,

these children are their own open sky,

their wings they make themselves.

Their language is different, meanings diverge,

if they are noisy, it does not matter.

Do not try to understand what they say:

these are the books of tomorrow's Nepal.

(no date; from Samsamayik Sajha Kavita 1983)

Berore the Dawn (Bihana Hunubhanda Pahile)

The sweepers have not risen

to come and sweep our floors,

no tinkling is heard from bangles

on arms unlocking doors,

no one has begun to daub

the yard below the stairs,[4] drops of dew have still to fall

from the petals of the flowers,

the birds have not yet stretched their wings,

they have not begun to sing.

Still there is no one about,

in the east no hint of light,

no cock has yet been heard to crow:

sleep, Nepali, sleep,

it is not yet time to rise.

(no date; from Samsamayik Sajha Kavita 1983

Krishnabhushan Bal (B. 1947)

Krishnabhushan Bal is one of the most powerful poets of recent times. All of his poems comment forcefully on contemporary social and political issues. "April Wind" (Chaitko Hava ) is an unambiguous call for radical change in Nepali society and something of a prophecy, too, because the political upheaval of 1990 reached its climax in April of that year; "Historical Matters" (Itihaska Kura ) bewails the "backwardness" of the kingdom.

April Wind (Chaitko Hava)

April has come to these lowlands,[5] the wind strips bare the trees

like a mad, demented elephant.

This is no breeze to merely grasp

the gentle scent of flowers:

it sweeps away the dust of ages,

fells ancient trees with ease.

This wind made most of the history we read,

this wind makes most of the history we write,

I may fear for my house of confidence,

but it blows down not only weak buildings,

it uproots not only frail voices;

it can blow away the ocean's waters,

and drive the rain from the sky.

[4] It is traditional for Hindu householders to smear their courtyards and so on with fresh mud or cow dung early each morning. This hardens to provide a clean, smooth floor surface.

[5] The month of Chait, or Chaitra, corresponds to the second half of March and the first half of April in the Western calendar.

And can I omit to say,

it dispels the clouds which cover this land,

it rips up the leaves of our incongruous history,

sounding the bugles of revolution.

Today it is filling the skies

with the whirlwind of a tree's old leaves:

contractors' houses, founded on profit,

cannot stand for long,

the clouds can no longer keep the sun

from warming people's backs.

A prayer flag flutters before my house,

furious in the wind,

the pipal tree sounds loud and free.

The wind has bypassed truth and peace,

rashly deciding to bring in the Spring.

If hindered, if blocked by a mountain,

who knows what might not happen?

May it not destroy the prayer flag,

may it not bring down the pipal tree

which gives us all cool shade.

April has come to the lowlands

with a wind like a crazy elephant.

Oh cooks with ladles and spoons in your hands,

beware of the fire!

Oh you who try to act as a father,

grabbing your whole family by its hair,

beware of the fire!

Beware of the wind!

(no date; from Samsamayik Sajha Kavita 1983)

Historical Matters (Itihaska Kura)

A moon of creation set foot here among us

and has only just gone on its way,

to the riverside steps, taking an air of excitement,

there to make it cold.

The city carries a great crush of dead bodies,

frightened like a kitten,

the streets are dumb amid dull footsteps.

There history stayed, and there we stayed, too.

To find out whether the rivers were sleeping,

we immersed the wood for our fires,

to discover whether the hills still slumbered,

we wandered from town to town.

When we found out these things for certain,

we were already washed away,

when we discovered these things for sure,

we had subsided with the land.

There history stayed, and we moved far behind,

branded by the Sagauli Treaty,

cursed by Sati,

we who saw Bhimsen uncremated.[6]

How long can the lamp go on burning,

wrapped in a sky of coldness?

How will the fallen trees stride out

from the banks of the Arun River?

The cock which just summoned the morning

is already plucked bare by a jackal,

a cloud has already hidden the sun

which glimmered just now on the hill.

Geography has cheated us both,

but we have defrauded history.

(no date; from Samsamayik Sajha Kavita 1983)

Bimal Nibha (B. 1952)

Like Hem Hamal, Bimal Nibha is a poet of gentle satire, and this poem mocks the escapism of the romantic nature-poetry that is still popular in Nepal.

Are You Quite Well, Oh Poet? (Ke Tapaimlai Sanchai Cha Kaviji?)

. . . flowers of many colors bloom,

bees are buzzing, birds are singing,

the sky is clear and spotless,

the river flows by swiftly ...

... but pardon me please, oh poet,

I break the flow of your poem,

to ask you—are you quite well?

[6] The Treaty of Sagauli (1816) ended a series of military clashes between the Nepalese and the forces of the British East India Company. Because the treaty deprived Nepal of some of its most fertile territories, many felt it to have been a humiliation. Bhimsen Thapa was the commander in chief of the Nepalese army, and therefore the most powerful man in Nepal, from 1804 until his assassination in 1837. For the Nepali belief that Nepal was cursed by a sati as she mounted her husband's funeral pyre, so that altruism would never be rewarded in Nepal, see Raj (1979, 29).

. . . the mountains stand with heads held high,

the cascades tumble, melodious sound,

the kites are wheeling in the sky,

a flute sounds sweetly from afar,

the breeze is whispering soft ...

but pardon me please, oh poet,

I must ask you this in your poem—

have you had enough to eat?

... the moon is spreading its coolness,

the night is fragrant, the body light,

the heart is overjoyed ...

... but pardon me please, oh poet,

again I interrupt—

Is rice very cheap in the marketplace?

Is rice very cheap in the marketplace?

Have you had enough to eat today?

Are you quite well, oh poet?

(no date; from Samsamayik Sajha Kavita 1983)

Ashesh Malla (B. 1954)

Malla was born in Dhankuta, in eastern Nepal, and is also known as a successful playwright. He continues a style of verse that was first made popular by Gopalprasad Rimal. In both of the poems translated here, concern is expressed for the exodus of hill Nepalis to the cities and lowlands in search of land and employment.

To the Children (Tiniharulai)

Little children should gambol and play,

cheerfully, clutching books,

carefree in the streets and fields,

beneath the piece of the sky they choose,

playing any game they please,

their lips all filled with Autumn.

Why do these strange children

bear the silence of pain in their eyes?

Why do their minds' dumb voices cry

that the wounds on their feet have not healed,

that their mothers and fathers who left seeking faith

have not returned from other towns?

These children's lips should bear smiles,

new buds should bloom in their cheeks,

why do they try to hide their hands,

wearing on one side a shower of rain,

on the other a slap of wind?

Books should be tucked under their arms,

but now they can go nowhere, they cannot rise

above the town which fills their eyes.

All they need is a mind,

to be able to see,

a warm human embrace,

a father's sweet kiss,

and a breast of mother's milk.

(no date; from Samsamayik Sajha Kavita 1983)

None Returned From the Capital (Rajdhanibata Pharke Pharkenan Uniharu)

Munching chiura[7] the old faiths came

to attend the capital's festive day;

they never returned from Pashupati's bare slopes,

from the softness of dawn sleeping wrapped in frost,

perhaps even now they are sipping the dew,

chanting God's name on some temple steps,

or moving dumb lips in the crowds and the noise,

their walking sticks lost on the streets,

feeling the void with trembling hands,

wrongly attired at pedestrian crossings.

They came to the capital seeking their country,

they entered the city they knew as Nepal,[8] freed, they will run to the streets

already auctioned in their name:

these are not the bare mountain valleys,

these are not. the lowlands' tax-free dusts[9] (in short, I call the capital

the headline of a newspaper).

Old fathers, come to the festival,

know nothing of its glorious tales;

perhaps they have listened to Scripture

and imagine entering Swasthani's palace.[10]

[7] Chiura is parched rice, a common staple among the poorer sections of Nepali society.

[8] Kathmandu is still often referred to as "Nepal" by people from outside the valley.

[9] This reference is to recent government policies that encourage landless people from the hills to settle in the lowland Tarai.

[10] Swasthani is a goddess of prosperity and fertility to whom women who wish to bear children often make a vow.

I fear they did not return,

waking cold perhaps beneath some statue;

so many gathered,

sucking chiura in toothless mouths.

Somewhere, small children await old fathers,

watching from walls in hill villages,

expecting blessed food and sweet stories.

They do not know of the few scraps of chiura

which now remain in the bag,

no one knows if they have returned;

where can they be?

There is no hint of them anywhere.

(no date; from Samsamayik Sajha Kavita 1983)

Minbahadur Bishta (B. 1954)

Bishta is a resourceful poet who criticizes political and economic conditions in Nepal with great verve. "What's in the Bastard Hills?" (Sala Pahadmem Kya Hai? ) mourns the environmental decay that is gathering pace in the hills of western Nepal and forcing farmers to abandon their ancestral lands. "Thus a Nation Pretends to Live" (Yasari Euta Rashtra Banchne Bahana Garcha ) is a satire on Nepal's dependence upon foreign aid donors.

What's in the Bastard Hills? (Sala Pahadmem Kya Hai?)

Springing quickly from its source,

it hurries here, and loiters there,

but never glances back;

instead, the river is kicking hard

against the sickly mountains

which stand like statues on its banks,

as it runs away, and leaves this land.

Young sons are walking out,

leaving the places they were born,

taking loved ones with them,

carrying bags, neatly tied

with red kerchiefs on their shoulders.

Khukuri knives hang from their waists,

dull and unpolished for years;

they tell their sick old parents

to look after homes, homes which are lifeless.

Soft petals of gentle flowers, tender leaves of green,

flying in every direction,

plucked up by unseasonal winds

blowing from unknown lands.

Trees stand bare and disfigured,

like soldiers on parade along mountain ranges.

Flocks of doves like destitutes

are driven from their homes

by incessant storms, the deluge

which ends the longest drought;

their bodies are soaked by rain:

no hope of food to eat,

no place for them to rest.

Thus there is nothing in the hills

on which to pen a poem,

you could even say there is nothing there

for anyone to write;

it's like the soldiers always say,

home for a few months' leave,

"What's in the bastard hills?"[11]

Surely there is something here:

dying mothers, newborn babies,

springs shedding sorrowful tears,

pools frozen like heaps of stone,

absolutely still,

where the rivers have left some dirty water

and a few frog shops

as they give up hope and leave,

a few old people tending their homes,

awaiting their time,

some mountains with finished faces,

some trees felled in their youth.

And there are the cooing destitutes,

piercing the heart, shedding tears of blood:

flocks of doves.

(no date; from Samsamayik Sajha Kavita 1983)

[11] Sala pahad : I have translated this as bastard (sala ) hills (pahad ). Sala , with the basic meaning of "brother-in-law," is a common term of abuse. By addressing a man as sala , one implies that one has had sexual relations with his sister. The term is also applied adjectivally to any object deserving of contempt, an application that is far beyond the original meaning. The soldiers' rhetorical question (sala pahadmem kya haim? ) is asked in Hindi. (See Hutt 1989a.)

Thus a Nation Pretends to Live (Yasari Euta Rashtra Banchne Bahana Garcha)

Honored friend,

this is Machapuchare, that is Annapurna,

over there stands the Dhaulagiri range.[12] You can see them with the naked eye,

you do not need binoculars.

Here I shall open a three-star hotel:

would you kindly make me a loan?

Dear guest,

this is the Koshi and that is the Gandak,

the blue over there is the Karnali.[13] You may have read in some papers

about the selling of Nepal's rivers.

That was a lie, sir.

Those rivers have given our regions their names,

we plan to generate power from them:

could you give us some help?

Respected visitor,

this is Kathmandu Valley.

Here there are three cities:

Kathmandu, Lalitpur, Bhaktapur.

Please cover your nose with a handkerchief,

no sewage system is possible,

the building of toilets has not been feasible.

Our next five-year plan has a clean city campaign:

could you make a donation?

(no date; from Samsamayik Sajha Kavita 1983)

Avinash Shreshtha (B. 1955)

Avinash Shreshtha was born in Gauhati, the state capital of Assam in northeastern India. His voice is unique among the younger generation of Nepali poets, and his work has caused a stir in Kathmandu literary circles. Avinash's poems are heavy with mystical symbolism; their beauty is indisputable, but their interpretation is the subject of vigorous debate.

Avinash Shreshtha's poems are collected in Samvedana o Samvedana (Feelings, Oh Feelings, 1981) and Pareva: Seta-Kala (Doves: Black and White, 1984).

[12] These mountains are seen prominently from Pokhara.

[13] These are three of Nepal's most important rivers.

A Spell (Moha)

I do not know from which Manasarovar there sprang

the Brahmaputra of my consciousness,[14] I do not know how far it will be

to the final sea of its ending.

The fisherman fears poverty,

the fish is afraid of the fisherman,

sleep is startled by a dream,

eyes are made dizzy by sleep;

greetings from the restless sea,

palms of ebb and flow together,[15] to the moon, to the sky.

Where does it hide, where?

pouring out boundless blue silence,

filling the eyes of the sky.

Has it collided somewhere

with the illusion of insoluble space,

or simply disappeared?

On a rain-soaked Indra-lotus night

in the month of Bhadau,[16] I do not know who it was that walked,

joined to rumor, body fragrant,

across the mind's unpeopled forests,

unseen.

(1986; from Kavita 1986)

Headland (Antarip)

A negro-black night

dozes in each eye

where cigarettes of disbelief are lit.

Where the solitude makes you forget your name,

the river your shape and the sea your limits,

there is a headland.

Oh Iravati,[17] through what lonely place do you flow?

[14] Manasarovar, a sacred lake on the Tibetan plateau, is the source of the great Brahmaputra River.

[15] This reference is to the gesture of greeting known as the namaste .

[16] The month of Bhadau, or Bhadra, corresponds to the second half of August and the first half of September in the Western calendar. This is the season of the late monsoon rains.

[17] Iravati is the sacred Ravi River in northern India.

In what desolation have you hidden hate?

Where is the innocent headland

of your fleshless love?

One blue star still twinkles

on the sky's frightened breast

on nights sunken in chants of pain.

(1986; from Kavita 1986)

Bishwabimohan Shreshtha (B. 1956)

Born in the Terhathum district of eastern Nepal, Bishwabimohan Shreshtha is recognized as one of the leading poets of the new generation and was awarded the Moti prize for poetry in 1987. The poem translated here describes the difficulty of pursuing a literary career in Nepal, where the struggle for basic needs is a more pressing concern.

Bishwabimohan Shreshtha's poems are collected in Bishwabimohanka Kehi Kavitaharu (Some Poems by Bishwabimohan Shreshtha, 1987).

Should I Earn My Daily Bread, or Should I Write a Poem? (Ma Bhat Jorum Ki Kavita Lekhum?)

At home my aged mother

watches for her son

on every festive day,

wondering if he will come

to help her make ends meet;

Each night in her lodgings,

my wife watches the door,

hoping that her husband will bring

something sweet and fine;

My daughter wears torn pajamas

and runs round telling tales

to neighbors, strangers, friends:

this winter father will bring her

a fine new suit of clothes;

My son, sent home from school,

plays all day in the dust

with crowds of local children;

he hopes father will send him

back to school this term;

The little one's asleep now,

teasing milkless breasts,

his nakedness forevermore

mocks my very manhood;

Speak not of brothers and sisters:

for them no work could be found,

for them no spouse was chosen;

How much longer can 1 go on

in my tattered coat and patched-up jacket,

holding together heaven and hell?

Tell me, oh respected friend,

with such an evening in my arms,

should I earn my daily bread,

or should I write a poem?

Forget the radio, papers, speeches,

speak not of slogans, marches, placards,

and if some time remains

do not push me into darkness

with affectionate intent.

It is hunger I endure,

a greater Everest by far

than any ideal or doctrine.

The drying softness of life,

learning's gentle kindness:

only these can defeat hunger.

It is done: do not make me hesitate

by relating the Buddha's story,

if your dreams delay me,

if your temptations beguile me,

if I do not work these fingers to the bone,

if I neglect to sell my sweat,

my parents, my wife, my children,

will all grow hungry and die;

I am tired, a beaten warrior,

at war with the stomach's demands.

How much longer can I go on

in my tattered coat and patched-up

jacket, holding together heaven and hell?

Tell me, oh respected friend,

with such an evening in my arms,

should I earn my daily bread

or should I write a poem?

I always bear upon my head

an Annapurna of need,

I always carry on my back

a Kanchenjunga of crisis,

how long can I fight this battle,

lifting a Machapuchare of costs

up onto my shoulders?

I believe that life should mean

flowing onward, a boon from God,

so do not mock my prayer.

Please try not to let me hear

of the horrors of the Falklands,

of massacres in Vietnam,

Afghanistan,

they are salt in my wounds.

Life is iron, I know you must

bite down hard upon it.

Life's a desolate shore, I know

you must water it with sweat,

but with what simile, what metaphor,

can I adorn and embellish this life?

How much longer can I go on

in my tattered coat and patched-up jacket,

holding together heaven and hell?

Tell me, oh respected friend,

with such an evening in my arms,

should I earn my daily bread

or should I write a poem?

(from B. Shreshtha 1987; also included in Samsamayik Sajha Kavita 1983)

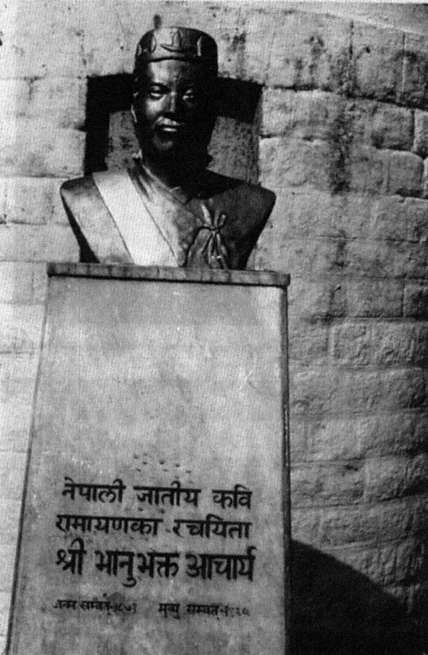

1.

Bust of Bhanubhakta Acharya, the adi kavi (founder poet), at Darjeeling.

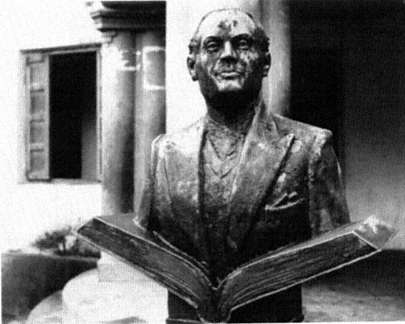

2.

Bust of Lakshmiprasad Devkota near his home in Dilli Bazar, Kathmandu.

3.

A verse from Devkota's "Like Nothing into Nothing," inscribed beneath

the bust in Kathmandu.

4.

Cover of the nineteenth edition of Lakshmiprasad

Devkota's classic Muna-Madan, published in 1988

in Kathmandu. Twenty-five thousand copies of this

43-page booklet were printed for this edition. A total

of 140,000 copies have been produced since the

fourteenth edition was published in 1976.

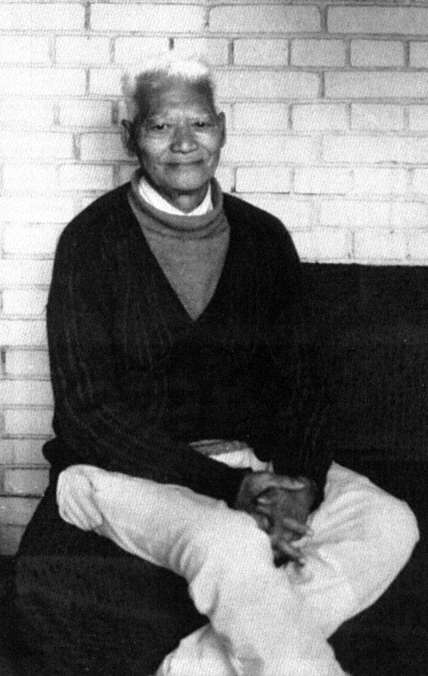

5.

Siddhicharan Shreshtha at his home in Om Bahal, Kathmandu.

6.

Kedar Man "Vyathit" at his home in Jyatha Tol, Kathmandu.

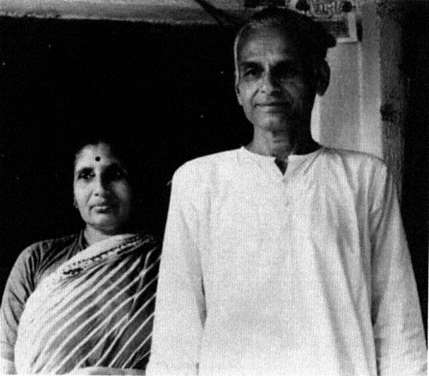

7.

Mohan Koirala and his wife at their home in Dilli Bazar, Kathmandu.

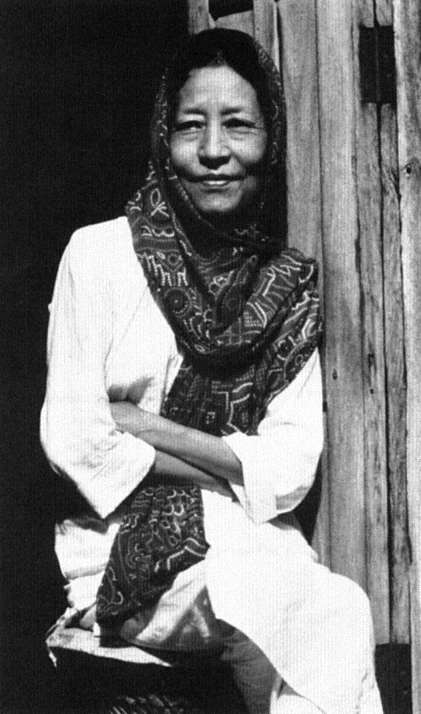

8.

Parijat at her home at Mehpin, Kathmandu.

9.

Banira Giri at her home in New Baneshwar, Kathmandu.

10.

Cover of Bairagi Kainla's collected

poems, published in Kathmandu

in 1974.

11.

The eleventh edition of Katha

Kusum, published in 1981 in Darjeeling.

Katha Kusum, the first anthology

of short stories in Nepali,

was initially published in 1938.