Preferred Citation: Hutt, Michael James. Himalayan Voices: An Introduction to Modern Nepali Literature. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1991 1991. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft729007x1/

| Himalayan VoicesAn Introduction to Modern Nepali LiteratureTranslated and Edited by |

Preferred Citation: Hutt, Michael James. Himalayan Voices: An Introduction to Modern Nepali Literature. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1991 1991. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft729007x1/

PREFACE

The compiler of any literary anthology is always liable to be accused of sins of omission and commission, and I do not expect to be spared. I began work on this project with the idea of producing two separate books: a much larger and more comprehensive selection of poems in English translation, including works by as many as forty poets, and an anthology of some thirty short stories. These objectives were modified for a number of reasons. It gradually became clear to me that the poetry of another culture can rarely be appreciated or understood fully if its authors are not properly introduced or presented in the context of their own historical and literary traditions. The approach I subsequently adopted was to provide an introduction to the works of a fairly limited number of important Nepali poets. At a later stage it dawned on me that although Nepali short stories contain a wealth of interesting material, many are simply less compelling in a strictly literary sense than are the more highly developed poetic genres.

Each poet who is the subject of a separate chapter in Part One of this book has been chosen for reasons of significance, and the importance of the contribution each has made to Nepali poetry is explained in an introductory preamble to the selection of translated poems. The farther back into the historical past one ventures, the easier it becomes to assess the importance of individual poets. Thus, it is unlikely that any Nepali will wish to quarrel with my choice of the first six poets. It is inevitably more difficult to predict who will come to be regarded in future years as the most important Nepali poets of the more recent past. In general, however, I have relied on the assessments of Nepali critics and anthologists in my choice of both poets and poems. If a poet appears regularly in the four anthologies published by the Royal Nepal Academy and Sajha

Prakashan, it seems safe to assume that he or she is considered significant. I have adopted a similar rule with regard to the selection of poems for translation, although it must be admitted that personal taste and the extent to which I have felt satisfied with my translations have also played a part in this process. Thus, some poems are translated here because Nepali critics agree that they are important; others appear simply because I have enjoyed them.

My aim in Part Two has been to present translations of some of the most interesting and best-known examples of the short story in Nepali, to demonstrate the extent to which they describe life in Nepal, and to give some indication of the way in which the genre has developed. This selection has been "boiled down" from my original collection of more than thirty translated stories and is presented as far as possible in order of first publication. Obviously, each story was originally written by a Nepali for a Nepali readership. It should also be borne in mind that the authors are from a particular section of Nepali society—the educated urban middle class—and that these stories therefore inevitably reflect the prejudices, perceptions, and preoccupations of members of that class. It is part of a translator's duty to explain and interpret, and I have tried to do this as unobtrusively as possible with a fairly brief introduction to the genre and its themes and with an explanation of Nepali terms and cultural references in brief footnotes to the texts. A number of Nepali words have been retained in these translations because no single English word could adequately translate them. More detailed explanations of such terms may be found in the glossary at the end of the book.

In selecting these stories for translation, I consulted with a number of scholars, critics, and authors in Kathmandu in the summer of 1988 and compiled a list of more than fifty important Nepali short story writers. Obviously, this list had to be shortened because the inclusion of one story by each writer would have produced a book of unmanageable and unpublishable proportions. It soon became clear that certain writers could be represented adequately by one story apiece but that justice would not be done to others if only one story of theirs was translated. Thus, an initial selection was made of thirty stories by twenty-two authors, of whom six were represented by two stories and one (Bishweshwar Prasad Koirala) by three. Once the authors had been selected, the problem of which stories to translate was solved with reference to critical opinion in Kathmandu and to the choices of the editors of the five important Nepali anthologies. These are Katha Kusum (Story Flower, 1938), the first anthology of short stories ever published in Nepali; Jhyalbata (From a Window, 1949), an anthology of twenty-five stories; Sajha Katha (Sajha Stories, 1968), which includes twenty-six of the most famous Nepali stories; Pachhis Varshaka Nepali Katha (25 Years of Nepali Stories,

1983), a collection of thirty-five of the best stories published between the establishment of the Royal Nepal Academy in 1957 and 1983; and Samsamayik Sajha Katha (Contemporary Sajha Stories, 1984), a supplement to Sajha Katha that contains thirty-seven more recent stories. My original intention had been to publish all thirty stories as a separate anthology, but, as I have explained, I later cut down the number of stories to what I consider an irreducible minimum. I hope that those that remain will serve to give a flavor of modern Nepali fiction.

I regret that stories by such noted Nepali authors as Pushkar Shamsher, Govindabahadur Malla Gothale, Shankar Koirala, Shailendra Sakar, Dhruba Sapkota, Pushkar Lohani, Jainendra Jivan, Jagdish Ghimiré, Kumar Nepal, Keshavraj Pindali, Ishwar Ballabh, Somadhwaja Bishta, Bhaupanthi, Devkumari Thapa, Anita Tuladhar, and Bhimnidhi Tiwari have not found their way into this collection. Some readers may also be surprised by the absence of two of Nepal's greatest writers— Lakshmiprasad Devkota and Balkrishna Sama—who both wrote a number of short stories. My opinion, shared by many Nepalis, is that Devkota's and Sama's greatest contributions were to the fields of poetry and drama in Nepali, not to fiction. This book might also be accused of ignoring to some extent the enormous contribution made by Nepali writers from India because most of the research on which the book is based was conducted in Nepal. Such, however, are the limitations inherent in a work of this nature. Let me conclude by saying that I hope that others will continue to investigate and translate Nepali literature, so that the gaps I have left may be filled and Nepal's rich literary heritage may be appreciated more fully in the world beyond the hills.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

It is difficult to state with any certainty when it was that I actually began work on this book because I first read and translated some of these poems and stories as long ago as 1980 while conducting research for a doctoral thesis. The project might well have taken another eight years to reach fruition had the British Academy not granted me a three-year research fellowship in Nepali in 1987. It is to that illustrious body that I am most deeply indebted.

I must also record my gratitude to innumerable members of staff at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London and particularly to Dr. David Matthews, who first taught me Nepali; to Professor Christopher Shackle, who encouraged me to maintain my involvement in this field; and to Dr. Ian Raeside, present head of the Department of Indology, who kindly agreed to host my fellowship.

The British Council and the Research Committee of the School were extremely generous in their support of visits to Nepal in 1987 and 1988. My thanks also to Dr. Nicholas Allen of Oxford University; to Professor J. C. Wright and Professor Lionel Caplan of SOAS for their help with some obscure mythological references; and to Dr. John Whelpton for helping me to unravel some of the historical background to these texts.

I have of course received an enormous amount of help from friends and colleagues in Nepal. Chief among these has been Mr. Abhi Subedi, who helped me to make many invaluable contacts in Kathmandu; spent long hours reading through the translations, often in consort with the authors themselves; and showed me great-hearted kindness in Nepal— earthquakes and monsoons notwithstanding. The assistance and hospitality of Mr. Peter Moss, the British Council's Representative in Nepal, are also gratefully acknowledged. The enthusiasm for this project ex-

pressed by Mohan Koirala, Banira Giri, Kedar Man Vyathit, Parijat, Siddhicharan Shreshtha, Bishwabimohan Shreshtha, Chuda Mani Bandhu, Ballabh Mani Dahal, Krishna Bhakta Shreshtha, Dayaram Sambhava, Bijay Malla, Krishna Chandra Singh Pradhan, Achyutaraman Adhikari and many other members of Kathmandu's literary community has been the single greatest spur to its completion. They are, after all, the true authors of this book.

My sincere thanks to Lynne Withey and Betsey Scheiner at the University of California Press and copyeditor Jan Kristiansson for the meticulous way in which they prepared this book for publication.

Finally, I must record my greatest debt of all: that which I owe to my dear Lucy, who has given me love and support and acquiesced gracefully to my long absences. To her I dedicate this book.

NOTE ON TRANSLITERATION

Because this book is intended primarily for the reader who knows no Nepali, I have not gone to great extremes to represent the exact Devanagari spellings of Nepali names and terms; I have sought instead to provide an adequate representation of their pronunciation. Any reader who is familiar with the Devanagari script, however, should have little difficulty in reconstructing original spellings. Differences in vowel length and between retroflex and dental consonants are indicated, but distinctions such as those that Devanagari makes between s and s, which are unimportant for the purposes of pronunciation, are glossed by presented both as sh. The temptation to follow the practice of spelling words such as Lakshmi Laxmi , or Bhupi Bhoopi has been resisted on aesthetic grounds. Nevertheless, some single consonants, such as v , may be pronounced in various ways: v, w, or b. In each case, the transliteration follows the most likely pronunciation. Vishvavimohan Shreshtha's first name is pronounced Bishwabimohan , and the poet actually spells it like this when required to do so. It would seem pedantic, not to say arrogant, to differ with a man over the spelling of his own name.

Long vowels are distinguished from short vowels by the addition of a macron: a/a, u/u, i/i. A is pronounced like the "a" in southern English "bus," whereas a is like "a" in English "father" or "bath," or occasionally harder, as in "hat." I is like the "i" in "hit," whereas i is like the "ee" in "week." U is like the "u" in "put," whereas u is like the "oo" in "moon." Most Devanagari consonants have aspirated, or "breathy," forms, represented here by the addition of an "h." Ordinary dental consonants are pronounced with the tongue against the back of the front teeth; retroflex consonants, indicated here by the addition of a dot beneath the dental form (t , d , n , and so on) are pronounced with the tongue pressed up into the palate.

INTRODUCTION

Nepal and Its Environment

Nepal is a Hindu kingdom, approximately equal in size to England with Wales, that lies along a 500-mile stretch of the eastern Himalaya between India and Tibet. The most striking feature of the country is its spectacular landscape, and the region's dramatic topography has been a crucial factor in its historical and cultural development since the most ancient times. From a strip of fertile lowland known as the Tarai in the south, Nepal rises in range after range of hills to the snow-covered crest of the main Himalayan range. Nepal's location between two great cultures and its previous isolation from the outside world have produced a rich and variegated mixture of ethnic groups, languages, and cultures. Because communication and travel in such mountainous country present enormous problems, the region remained politically fragmented until the recent historical past. In the south, the jungles and malarial swamps of the Tarai prevented both settlement and foreign military incursions, whereas the far north was cold, lofty, and inhospitable. The heartlands of Nepal have therefore always been the hill areas between these two extremes and, more particularly, the intermontane valleys with their fertile soils and equable climate.

Since the early medieval period, the Kathmandu Valley (often still known simply as Nepal) has been the most prosperous and sophisticated part of this region, and it is still famous for the distinctive arts and architecture of its most ancient inhabitants, the Newars. The hill regions are the home of an enormous variety of different ethnic groups, each with its own language. Although Hinduism predominates, Buddhism and minor local cults are strong. A large number of petty states existed

within the present-day borders of Nepal until the mid-eighteenth century (within the central valley alone, there were three separate Newar kingdoms); but all of these were overcome by the tiny principality of Gorkha within only a few decades. Gorkha's campaign of conquest and unification was inspired and led by the remarkable king, Prithvinarayan Shah, whose forces finally took the Kathmandu Valley in 1769. Prithvinarayan is now revered as the father of the modern nation-state. Nepal assumed its present proportions early in the nineteenth century after a series of battles with the British East India Company in 1815 and 1816. A treaty imposed on the Nepalis and signed at Sagauli, now in Bihar, India, was a severe blow to national pride.

Modern History

As a Hindu kingdom, Nepal has been ruled since its "unification" by a series of Gorkhali monarchs—the Shah dynasty—who claim a lineage that stretches back to ancient origins in the Rajput states of western India. For most of the time between the conquest of Kathmandu, the new nation's capital, and the mid-nineteenth century, however, a minor occupied the throne. This led to an almost continual and often bloody struggle for power among a number of rival families. An abrupt end was brought to this period of political chaos in 1846, when Jang Bahadur, head of the powerful Kunwar family, contrived to have most of his rivals killed off in an event now known as the Kot Massacre, the kot being a courtyard of the royal palace in which it took place. He subsequently became a virtual dictator, and the massacre inaugurated more than a century of rule by a succession of "prime ministers" who styled themselves Rana .

Jang Bahadur laid down the foundations of the Rana regime during his thirty-one years in power: the Ranas' primary concern was political stability, and they were generally supported by the British in India. Foreigners were barred almost totally during the nineteenth century, the kings were made virtual prisoners in their palaces, the office of prime minister became hereditary, and all foreign ideologies were viewed with considerable suspicion. Although it can be argued that the Rana governments saved Nepal from the threat of annexation to British India., it is quite evident that their conservative policies severely retarded the development of the kingdom. Educational policy is an important case in point. Until after World War I, education was provided only for the children of the elite in Kathmandu, and the national literacy rate remained abysmally low. The sons of high-caste families followed tradi-

tional modes of education: they studied the Hindu scriptures and the Sanskrit language and often traveled to the ancient centers of learning in India for their studies. For most of the people, however, social and educational advancement remained an impossibility, and subsistence farming was the only means of support.

After each world war, thousands of young men returned to Nepal from the British and Indian armies, bringing with them a much wider perspective on the world. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Nepal lagged behind even India in every aspect of development; roads, hospitals, schools, and industries were conspicuous by their absence. The nation's backward condition was readily apparent to the returnees, and the Ranas' hold on power became vulnerable to criticism from a growing class of educated and disaffected Nepalis. Despite a number of palliative measures taken to assuage political opposition, and despite periods of harsh repression exemplified by the 1941 execution of members of an illegal political organization, the Praja Parishad, the government's position became precarious after the departure of the British from India. By 1950 the main opposition group, the Nepali Congress, had begun to mount an armed insurrection, and early in 1951 the king, Tribhuvan, was restored to power in a series of events now called the "revolution" of 1950-1951. These events marked the advent of democracy in Nepal, and most Nepali historians regard 1950 as the beginning of the modern period of their history.

Since this revolution, Nepal has sought to enhance its national unity and identity and to establish viable political institutions and processes. The first decade of Nepali democracy was a troubled period characterized by vacillatory policies, the collapse of several short-lived administrations, and obstructive factionalism. In 1959 the Nepali Congress achieved a sweeping victory in the nation's first ever general election, but the Congress's program of radical reforms met with stiff opposition. In 1960 King Mahendra revoked the constitution, dismissed the government, and imprisoned its leaders, alleging that the Congress had failed to provide national leadership or maintain law and order. King Mahendra and his supporters also argued that the country's recent political instability had proved that parliamentary democracy was an alien system unsuited to Nepal. After 1960 Mahendra and his son and successor, Birendra, developed and refined a new system of Panchayat democracy based on a formal structure of representation from the "grass roots" up to national level. For most of this time all political parties were banned. Muted dissent flared up into student riots in the late 1970s, and a national referendum was conducted in 1980 to ascertain the people's will with regard to the national political system. The Panchayat system

was vindicated by a slim majority in this referendum, but rumbles of unrest continued to recur from time to time.

Toward the end of 1989 the banned Nepali Congress Party joined with other opposition groupings to launch the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD). The situation seemed ripe for change. A dispute with India concerning trade and transit agreements had caused severe shortages of basic commodities in Nepal. The continued ban on political parties meant that opposition activists faced increasingly harsh repression. Educated Nepalis found the pace of development frustratingly slow, particularly in view of the massive sums of foreign aid that they knew had poured into Nepal since the 1950s. Strong rumors circulated of corruption in high places, and many of these rumors implicated members of the royal family. Initially, the government responded harshly to the strikes and demonstrations the MRD had organized. Thousands were arrested and many newspapers were censored or banned. Dozens of demonstrators died in police actions during February and March 1990. On April 6, police fired on a large crowd of unarmed demonstrators who were marching on the royal palace in Kathmandu, and scores of marchers died. After this tragedy, the government capitulated. A curfew was declared to restore public order, the ban on political parties was lifted for the first time in thirty years, and a general amnesty was declared. After a brief period of intense negotiation, the king accepted a constitutional role, and an interim government was set up to redraft the country's constitution and to supervise elections in 1991.

After 1951 Nepal "opened up" to the outside world, becoming an active member of the international community, a popular tourist destination, and a major recipient of foreign aid. Massive schemes of road construction, health care, educational provision, power generation, and so on have been in progress throughout this period, and despite the unpopularity of the Panchayat system and of certain members of the royal family, King Birendra himself has always been considered an essential symbol of national identity and unity. Nevertheless, Nepal's future remains uncertain. It is still one of the world's ten poorest countries and faces such problems as the rapid growth of a population almost entirely dependent on land, severe ecological decline and consequent landlessness, and the growth of a class of educated but underemployed young whose thirst for change can only have increased during the early months of 1990. The events of recent history are referred to regularly in Nepali literature, and writers have not shied away from addressing current issues with insight and vigor. Because most of the research for this book was completed in 1988, the poems and stories translated here make no reference to the momentous events that occurred only two years

later, although some contain hints of the circumstances that produced the "revolution."

Nepali Literature: Antecedents

Nepali is an Indo-European language that is closely related to the other major languages of northern India, such as Hindi and Bengali. Approximately 17 million people speak Nepali, of whom perhaps one-third have acquired the language in addition to the mother tongue of their own ethnic group. The great majority of Nepali speakers, of course, live within the borders of modern Nepal, but Nepali is also the dominant language of the Darjeeling district of West Bengal, Sikkim, and parts of southern Bhutan and Assam. Substantial Nepali communities have grown up in north Indian cities such as Patna, New Delhi, and Banaras. For at least three centuries, Nepali has fulfilled the need for a "link language" or lingua franca among the various communities of the eastern Himalaya, a region of extraordinary linguistic diversity. During the past few decades, Nepali's prestige as a major language of South Asia has also grown considerably. In 1958 it was formally declared to be the national language of Nepal and was thus invested with an important role in the promotion of national unity. More recently, it was recognized as a major Indian literary language by the Sahitya Akademi in New Delhi, India's foremost institution for the promotion of vernacular literatures.

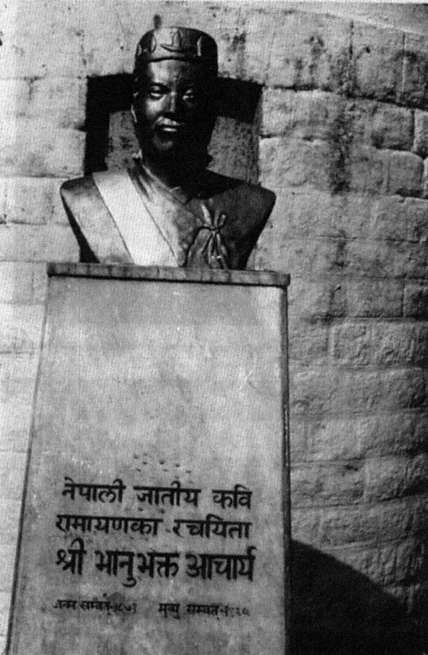

The oldest specimens of written Nepali extant are royal edicts from western Nepal, inscribed on stelae and copperplates, that date from the thirteenth century. Other than epigraphic material, however, very little Nepali literature has been discovered that dates back further than the seventeenth century. Nepali literature is therefore a much newer phenomenon than is literature in certain other languages of the region; Newari, for instance, has a rich literary tradition that dates back at least five hundred years. The translations into Nepali from Sanskrit scripture, royal biographies, and medicinal treatises that emanate from the seventeenth century possess very little literary merit, and the first Nepali poet of any real stature was Suvanand Das, who composed panegyric verse in praise of the king of Gorkha, Prithvinarayan Shah. Although the works of several other quite interesting eighteenth-century Nepali poets have been preserved and published, it is to a Brahman named Bhanubhakta Acharya (1814-1868) that Nepali literature really owes its first major work.

Bhanubhakta Acharya played a fundamental role in the development of Nepali as a literary language and is therefore honored as its "founder

poet" (adi-kavi ).[1] Obviously, he was by no means the first person ever to compose Nepali verse, but his rendering of the Ramayana epic into simple, idiomatic, rhyming Nepali was entirely without known precedent. in the language. Until Bhanubhakta,[2] few Nepali writers had been able to shake off the influence of the more sophisticated Indian literatures. As a consequence, their literary language was heavily larded with Sanskrit philosophical terms, or else it borrowed extensively from the languages of adjacent regions of India that possessed more developed literatures. Hindi devotional verse was an obvious source for such borrowings. Nowadays, Nepali writers come from various strata of society and strive to distance their language from Hindi, to which Nepali is quite closely related and with which it shares much of its word stock. These efforts are inspired partly by a nationalism that was largely invisible among the high-caste Nepali elites that monopolized the literary culture of Nepal in earlier centuries. Bhanubhakta's Ramayana was the first example of a Hindu epic that had not merely been translated into the Nepali language but had been "Nepali-ised" in every other aspect as well. It is still among the most important and best-loved works of Nepali literature, and along with Bhanubhakta's other works it became a model for subsequent writers.

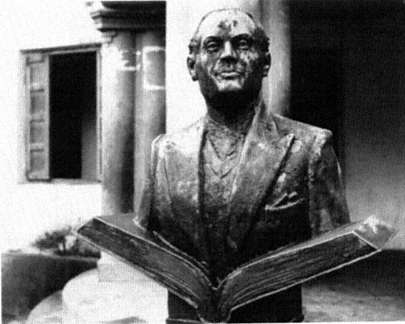

The second great writer in the history of Nepali literature, Motiram Bhatta (1866-1896), was an enthusiastic literary activist inspired by the example of the Indian writers who were organizing themselves in Banaras, where Motiram spent about twenty years of his short life. Bhatta was the first to recognize the significance of Bhanubhakta's Ramayana, and it was due to Bhatta's efforts that the poem was first published in 1887, some forty years after its composition. The Ramayana was followed four years later by Bhatta's biography of Bhanubhakta (M. Bhatta [1891] 1964). This is a delightful narrative interspersed with poems, but its historical authenticity is open to question. Bhatta subsequently became concerned about increasing the prestige of Nepali literature: he gathered groups of contemporaries about him in both Banaras and Kathmandu, encouraging literary debate and undertaking publishing projects. Through his own writings, he also attempted to broaden the scope of Nepali poetry, which was still largely confined to devotional verse, by developing interest in other genres such as the Urdu lyric known as the gazal (a Persian meter used in popular love songs) and the "erotic" style

[1] The term adi-kavi translates literally as "first" or "prime" poet.

[2] Nepali writers do not necessarily refer to people by the names that a Western reader might assume to be surnames because these are often impersonal titles (Acharya , for instance, translates as preceptor) or exceedingly common caste designations. I have followed the Nepali practice: because Nepalis do not refer to their "founder poet" as Acharya , or their "laureate" as Paudyal , there seems no need for us to do so either.

of shringar poetry. This latter genre, which celebrates the beauty of the female form in heavily stylized and allegorical language, is now generally considered decadent and indulgent, but it retains a few exponents among older poets. Kedar Man Vyathit's "Woman: Flavor, Sweetness, Brightness " (Nari: Rasa, Madhurya, Aloka ) is an example of modern shringar poetry.

Bhatta and his contemporaries prepared the ground for the growth of a body of creative literature in the Nepali language that would eventually enhance its prestige beyond measure. At the turn of the century, however, this process had barely begun. There were very few printing presses in Nepal and even fewer commercial publishers. The grammar and spelling of written Nepali remained completely unstandardized. The almost total absence of facilities offering public education meant that literacy was still the exclusive preserve of the powerful elites. The scope of existing Nepali literature was governed and limited by traditional convention and the somewhat decadent tastes of a tiny readership. The development and enrichment of Nepali literature that have taken place since the early twentieth century can only be described as remarkable.

The first signs of a literary awakening are actually to be found in a number of important government initiatives. A tradition of formal journalism was established in 1901 when the unusually liberal Rana ruler Deva Shamsher established the Gorkhapatra (Gorkha Paper). This newspaper, which is now published daily, is the official organ of the government of Nepal, and during the first thirty years of its existence it was the only periodical publication to be produced within the kingdom. It therefore provided a much-needed forum for the publication of poems, stories, and articles. The Rana administration headed by Chandra Shamsher (r. 1901-1929) also sought to promote Nepali literature by establishing the Gorkha (later Nepali) Bhasha Prakashini Samiti (Gorkha Language Publication Committee) in 1913. Chandra Shamsher is reputed to have declared, "There aren't even any books in Nepali! Just reading the Krishnacharitra and the Ramayana is not enough!" (Dhungana 1972, 29).[3] The committee had a dual role, however: as well as publishing books that met with its approval, it also operated a strong code of censorship:

If anyone wishes to publish a book, he must first bring it to the committee for inspection. No book may be published without the stamp of the committee's approval.... If a book is published without the committee's ap-

[3] The Krishnacharitra is a poem of 169 verses by Vasant Sharma (1803-1890) that narrates the legends of Krishna and enjoyed some popularity in Nepal during the nineteenth century.

proval, its publisher will be fined 50 rupees. If the contents of this book are deemed to be improper, all copies will be seized and punishment proclaimed and meted out. (Bhattarai 1976, 30)

Although this law was not enforced very consistently, there were periods during which offending writers were punished with extreme severity. The committee therefore came to be regarded with suspicion, and because it maintained an effective monopoly over Nepali publishing inside Nepal until the 1930s, poets and writers who wished to escape the overbearing censorship of their work had to publish, and even live, in Indian towns, most notably Banaras and Darjeeling. The relative conservatism of early works by poets such as Lekhnath Paudyal and Lakshmiprasad Devkota is explained partially by the fact that they resided in Kathmandu and therefore had to exercise extreme caution. Periodical publications, such as Sundari (The Beautiful, established 1906), Madhavi (1908), Gorkhali (1916), and the Nepali Sahitya Sammelan Patrika (Nepali Literature Association Journal, 1932),[4] that emanated from Nepali communities in India played a crucial role in the development of Nepali literature during the first few decades of the century. Indeed, Balkrishna Sama is quoted as once having said, "What Darjeeling thinks today, Nepal thinks tomorrow" (Giri & Pariyar 1977, 5).

In my discussion of Nepali literature I have avoided as far as possible the question of modernity because any division of literature into the categories "modern" and "premodern" is inevitably contentious. Nevertheless, the concept of modernity is of central concern to Nepali writers and critics when they consider the development of their literature. Some consider Bhatta, Lekhnath, or Guruprasad Mainali to be the founders of the modern era; others regard the political changes of 1950 as a watershed. These assessments are based upon a number of assumptions. It is held to be axiomatic, for instance, that religious or devotional literature is "old-fashioned" and that the modern writer should concentrate on secular themes. Time-honored forms and conventions inherited from Sanskrit literature have come to be considered restrictive; the abandonment by many poets of metrical forms and the development of prose genres are therefore regarded as major steps forward. In fiction, social realism came to be highly prized, and Western genres such as the novel and the short story were adopted and developed. This impulse to modernize Nepali literature was closely linked to a widespread desire for greater freedom of thought and expression and a growing interest in, and exposure to, the world outside Nepal.

[4] This was the journal of the Nepali Sahitya Sammelan (Nepali Literature Association), founded in Darjeeling in 1924. The association is still active today and produces a journal, Diyalo (The Lamp).

Perhaps the most important event in this process was the appearance of Kathmandu's first literary journal, the monthly Sharada , in 1934. Sharada , named after the goddess of the arts, Saraswati, was published with the help of a government subsidy under a regime headed by Juddha Shamsher that initially gave ground to demands for reform and liberalization. Described by Yadunath Khanal as "a product of an unwritten, silent compromise, allowed and accepted as an experiment, between the authorities and the rising impatient intellectuals" (1977, 236), Sharada provided a vital forum for Nepalis to publish their works within the kingdom itself. In a sense, this journal also gave birth to some of Nepal's first "modern" writers. Between 1936 and 1963, when its publication ceased, Sharada published nearly two hundred poems by Siddhicharan, Lekhnath, Rimal, Sama, and Devkota alone, as well as innumerable stories by Sama, Bishweshwar Prasad Koirala, Bhavani Bhikshu, and others (Subedi 1978, 7-9). It is therefore from the Sharada era and the years that followed that most of the works translated here emanate.

PART ONE

THE POETS OF NEPAL

Nepali Poetry

Poetry is the richest genre of twentieth-century Nepali literature. Although the short story has developed strongly, the drama holds its ground in the face of fierce competition from the cinema, and the novel is increasingly popular, almost every Nepali writer composes poetry. Since the appearance of Sharada , Nepali poetry has become diverse and sophisticated. The poets I have selected for inclusion represent different stages and strands of this development, and I have attempted to present them in an order that reflects the chronology of literary change. The direction that this process of evolution has taken should be clear from the introduction to individual poets and the translations of their poems. Here, a few general comments are offered by way of introduction.

Lekhnath Paudyal, Balkrishna Sama, and Lakshmiprasad Devkota were undoubtedly the founders of twentieth-century Nepali poetry, and each was a distinctly different poet. Lekhnath was the supreme exponent of meter, alliteration, and melody and the first to perfect the art of formal composition in Nepali. His impact on poets contemporary with him was powerful, eventually producing a kind of "school." Although his influence has waned, this school retains some notable members.[1] Sama was primarily a dramatist, but his poems were also important. He began as a disciple of Lekhnath but later rebelled against the restraints of conventional forms with the same vigor that he brought to his opposition to Rana autocracy. Sama's compositions are colored by sensitivity, intellectualism, and clarity, and because of his role as a social reformer and the accessibility of his work, he is still highly respected. Both Lekhnath

[1] These include Madhav Prasad Ghimire (b. 1919), whose long lyric poem on the loss of his wife, Gauri (1947), remains extremely popular.

and Sama were deliberate, methodical craftsmen and masters of particular modes of poetic composition, but the erratic genius of Lakshmiprasad Devkota brought an entirely new tone and spirit to Nepali poetry. Early in his career, he took the revolutionary step of using folk meters in the long narrative poems that are now among the most popular works of Nepali literature. Later, he produced the greatest epics of his language and finally, adopting free-verse forms, he composed some of its most eloquent poems. It would be difficult to overstate Devkota's importance in the modern literature of Nepal: his appearance on the scene has been compared to that of a meteor in the sky or as Nepali poetry reaching full maturity "with a kind of explosion" (Rubin 1980, 4).

The Sharada era produced poets who were influenced by their three great contemporaries, but also made their own distinctive contributions to the development of the genre. In his early years, Siddhicharan was obviously a disciple of Devkota, but his poems are calmer, clearer, and less rhapsodic. Vyathit also had much in common with Lekhnath, but he differed in his obvious social concern and his gift for composing short epigrammatic poems. Rimal was motivated principally by his political views, but he also did much to establish free verse and the prose poem in Nepali. His influence is more apparent in the work of young poets today than is that of most of his contemporaries. The Sharada poets were men who were in their prime during the 1940s and 1950s, although both Siddhicharan and Vyathit remain active today. The revolution of 1950-1951 certainly brought an atmosphere of greater freedom to Nepal, and a large number of works were published that had been withheld for fear of censorship. Few immediate changes took place in the Nepali literary scene, however, and the prerevolutionary poets continued to occupy a preeminent position until the following decade.

During the 1960s, Nepali poetry departed quite radically from the norms of the preceding twenty-five years, which was a result of the unprecedented changes that occurred in Nepali society in general and in intellectual circles in particular. After 1960, a new literary journal, Ruprekha (Outline) quickly became Nepal's major organ for aspiring new writers. Among these was Mohan Koirala, arguably the most significant poet to have emerged in Nepal since Devkota. The philosophical outlook of the generation of poets who emerged after 1960 differed from that of its predecessors in many respects. The immense expansion of education spread literacy throughout Nepal and produced a generation of graduates who were familiar with philosophies and literatures other than their own. The initial effects of this intellectual opening out in Nepal could be seen clearly in the poetry of the Third Dimension movement and particularly in the work of Bairagi Kainla and ÌIshwar Ballabh. The new poetry of the 1960s was full of obscure mythological references and

apparently meaningless imagery; this "cult of obscurantism" also influenced later poets, such as Banira Giri. It was coupled with a sense of pessimism and social alienation engendered by lack of opportunity in Nepal, which is expressed poignantly by the novelist and poet Parijat and angrily by Haribhakta Katuval.

The emergence of Bhupi Sherchan brought about further changes in the language and tone of Nepali poetry as well as in its purpose. His satire, humor, and anger were expressed in rhythmic free-verse forms, and the simplicity of his diction signified an urge to speak to a mass readership, not just to the members of the intellectual elite. During the 1960s, Nepali poetry seemed divorced from the realities of the society that produced it, but in the decade that followed it again addressed social and political issues in a language stripped of earlier pretensions. Poetry reassumed the role it had played during the Sharada era, once again becoming a medium for the expression of social criticism and political dissent. This trend reached a kind of climax in the "street poetry revolution" of 1979-1980, and Nepali writers played an important role in the political upheavals of February-April 1990 (Hutt 1990). This would surely have been a source of satisfaction to the mahakavi (great poet) Lakshmiprasad Devkota, who once wrote:

Our social and political contexts demand a revision in spirit and in style. We must speak to our times. The politicians and demagogues do it the wrong way, through mechanical loudspeakers. Ours should be the still, small voice of the quick, knowing heart. We are too poor to educate the nation to high standards all at one jump. Nor is it possible to kill the time factor. But there is a greater thing we can do and must do for the present day and the living generation. We can make the masses read us if we read their innermost visions first. (1981, 3)

Almost every educated Nepali turns his or her hand to the composition of poetry at some stage of life. In previous centuries, poetic composition was considered a scholarly and quasi-religious exercise that was closely linked to scriptural learning. It therefore remained the almost exclusive preserve of the Brahman male. Today, however, Nepali poets come from a variety of ethnic groups. Among those whose poems are translated here, there are not only Brahmans but also Newars, a Limbu, a Thakali, and a Tamang, and although it is still rather more usual for a poet to be male, the number of highly regarded women poets is growing steadily. Even members of Nepal's royal family have published poetry: the late king Mahendra (M. B. B. Shah) wrote some very popular romantic poems, and the present queen, writing as Chandani Shah, has recently published a collection of songs.

The Nepali literary world is centered in two Himalayan towns: Kath-

mandu, the capital of Nepal, and Darjeeling, in the Himalayan foothills of the Indian state of West Bengal. Other cities, notably Banaras, served as publishing centers during the period of Rana rule in Nepal, but their importance has diminished in recent years. Until the fall of the Ranas, some of the most innovative Nepali writers were active in Darjeeling (the novelist Lainsingh Bangdel and the poet Agam Singh Giri are especially worthy of note), and fundamental work was also done by people such as Paras Mani Pradhan to reform and standardize the literary language. In more recent years, Darjeeling Nepalis have been concerned with establishing their identity as a distinct ethnic and linguistic group within India and with distancing themselves from Nepal. Thus, the links between the two towns have weakened to the extent that writers are sometimes described as a "Darjeeling poet" or a "Kathmandu poet" as if the two categories were in some way exclusive. This difference is also underscored by minor differences in dialect between the two centers.

It has always been well-nigh impossible for a Nepali writer to earn a livelihood from literary work alone. All poets therefore support themselves with income from other sources. Lekhnath was a family priest and teacher of Sanskrit; Devkota supported his family with private tutorial work and occasionally held posts in government institutions. Nowadays, poets may be college lecturers (Banira Giri), or they may be employed in biscuit factories (Bishwabimohan Shreshtha). Many are also involved in the production of literary journals or in the activities of governmental and voluntary literary organizations. Devkota, for instance, edited the influential journal Indreni (Rainbow) and was also employed by the Nepali Bhashanuvad Parishad (Nepali Translation Council) from 1943 to 1946. Sama became vice-chancellor of the Royal Nepal Academy, as did Vyathit. Both Rimal and Siddhicharan were for some time editors of Sharada , and nowadays many younger poets are active in associations such as the Sahityik Patrakar Sangha (Literary Writers' Association) or the Sirjanshil Sahityik Samaj (Creative Literature Society), which organize readings, publish journals, and attempt to claim a wider audience for Nepali literature.

There are various ways in which Nepal rewards its most accomplished poets. Rajakiya Pragya Pratishthan (the Royal Nepal Academy), Nepal's foremost institution for the promotion of the kingdom's arts and culture, was founded in 1957 and now grants salaried memberships to leading writers and scholars for periods of five years. Academy members are thereby enabled to devote themselves to creative and scholarly work without the need for a subsidiary income. The period during which Kedar Man Vyathit was in charge of the academy is remembered as a golden age for Nepali poetry, but in general the scale of the academy's activities

is limited by budgetary constraints. Nevertheless, the academy is a major poetry publisher and has produced many of the anthologies and collections upon which I have drawn for the purpose of this book. The academy also produces a monthly poetry journal, Kavita (Poetry), edited until his recent demise by Bhupi Sherchan, and awards annual prizes to prominent writers; these include the Tribhuvan Puraskar, a sum of money equivalent to two or three years of a professional salary.

Another important institution is the Madan Puraskar Guthi (Madan Prize Guild), founded in 1955 and based in the city of Patan (Lalitpur). The Guthi maintains the single largest library of Nepali books, produces the scholarly literary journal Nepali , and awards two annual prizes (Madan Puraskar) to the year's best literary book and nonliterary book in Nepali.

Sajha Prakashan (Sajha Publishers) is the largest commercial publisher of Nepali books, with a list of nearly six hundred titles. It assumed the publishing role of the Nepali Bhasha Prakashini Samiti (Nepali Language Publications Committee) in 1964 and established an annual literary prize, the Sajha Puraskar, in 1967. Since 1982 Sajha Prakashan has also produced another important literary journal, Garima (Dignity). The Gorkhapatra Sansthan (Gorkhapatra Corporation) produces the daily newspaper Gorkhapatra and the literary monthly Madhupark (Libation). The latter publication has become the kingdom's most sophisticated periodical under the editorship of Krishnabhakta Shreshtha, who is himself a poet of some renown. With Garima, Bagar (The Shore, an independently produced poetry journal), and the academy's Kavita (Poetry), Madhupark is now among the leading journals for the promotion of modern Nepali poetry. The monthly appearance of each of these journals is eagerly awaited by the literary community of Kathmandu, many of whose members congregate each evening around the old pipal tree on New Road. Madhupark in particular has a wide circulation outside the capital. In India, too, institutions such as Darjeeling's Nepali Sahitya Sammelan (Nepali Literature Association) and the West Bengal government's Nepali Academy produce noted journals and award annual literary prizes.

Despite the limited nature of official support for publishing and literary ventures in Nepal, the literary scene is vibrant. The days when Nepali poets had to undertake long periods of exile to escape censorship, fines, and imprisonment have passed, but until April 1990 the strictures of various laws regarding public security, national unity, party political activity, and defamation of the royal family still made writers cautious. With increasing frequency during the 1980s, writers were detained, newspapers and journals were banned, and editors were fined.

But poetry remained the most vital and innovative genre and the medium through which sentiments and opinions on contemporary social and political issues were most frequently expressed. In Nepal, poets gather regularly for kavi-sammelan (reading sessions), and the status of "published poet" is eagerly sought. Most collections and anthologies produced by the major publishers have first editions of 1,000 copies—a fairly substantial quantity by most standards. Literary communities exist in both Kathmandu and Darjeeling, with the inevitable loyalties, factions, and critics. Books and articles on Nepali poetry abound, and critics such as Taranath Sharma (formerly known as Tanasarma), Ishwar Baral, and Abhi Subedi are highly respected.

Features of Nepali Poetry

The last eighty years have seen a gradual drift away from traditional forms in Nepali verse, although a few poets do still employ classical meters. Until the late nineteenth century, however, almost all Nepali poetry fulfilled the requirements of Sanskrit prosody and was usually composed to capture and convey one of the nine rasa. Rasa literally means "juice," but in the context of the arts it has the sense of "aesthetic quality" or "mood." The concept of rasa tended to dictate and limit the number of themes and topics deemed appropriate for poetry.

Classical Sanskrit meters, many of which are derived from ancient Vedic forms, are based on quantity and are extremely strict. A syllable with a long vowel is considered long, or "heavy," whereas a syllable is short, or "light," when it contains only a short vowel. Whether a syllable is followed by a single consonant or a conjunct consonant also affects its metrical length. The simplest classical meter, and consequently one of the most commonly used, is the anushtubh (or anushtup ), often referred to simply as shloka , "stanza." This allows nine of the sixteen syllables of each line to be either long or short and therefore provides an unusual degree of flexibility. In most other meters, however, the quantity of each syllable is rigidly determined. The shardula-vikridita that Bhanubhakta adopted in his Ramayana epic is a typical example. Each line of verse in this meter must contain nineteen syllables with a caesura after the twelfth, and the value of each and every syllable is dictated with no scope for adaptation or compromise.

Evidently, the ability to compose metrical verse that retains a sense of freshness and spontaneity is a skill that can be acquired only through diligent study and has therefore remained the preserve of the more erudite, high-caste sections of society. Most Nepali poets now regard these rules and conventions as restrictive, outdated, and elitist, especially

because they also extend to considerations of theme and structure. Yet it is significant that the skill to compose poetry in a classical mode was considered an important part of a poet's repertoire until quite recently. Balkrishna Sama used Vedic meters even in some of his later poems, and Devkota gave a dazzling display of his virtuosity in the Shakuntala Mahakavya (The Epic of Shakuntala) by employing no less than twenty different meters.

The first attempts to break the stranglehold of classical conventions were made during the 1920s and 1930s when poets such as Devkota began to use meters and rhythms taken from Nepali folk songs. The musical jhyaure became especially popular and retains some currency today. Such developments were part of a more general trend toward the definition of a specifically Nepali identity distinct from pan-Indian cultural and literary traditions. These changes could also be regarded as a literary manifestation of the Nepali nationalism that eventually toppled the Rana autocracy.

In the years that followed, many poets abandoned meter altogether. Nonmetrical Nepali verse is termed gadya-kavita , literally "prose poetry." Most nonmetrical poems can be described as free verse, but a few works do exist, such as Sama's "Sight of the Incarnation" (Avatar-Darshan ), that seem to be conscious efforts to compose genuine prose poems. As Nepali poetry departed from the conventions of its Sanskrit antecedents, its language also changed. The arcane Sanskrit vocabulary required by classical formulas was no longer relevant. When poets began to address contemporary issues and to dispense with traditional forms, they also strove to make their works more readily comprehensible. The vocabulary of the "old" poetry was therefore rapidly discarded.

Nepali poetry is composed in several distinct generic forms. The most common is, of course, the simple "poem" (kavita ) written in metrical or free-verse form. A khanda-kavya , "episodic poem," is longer and is usually published as a book in its own right. It consists of either a description or a narrative divided into chapters of equal length. Devkota's narrative poem Muna-Nadan (Muna and Madan) and Lekhnath's description of the seasons, Ritu-Vichara (Reflections on the Seasons), are two famous examples. Because the khanda-kavya is a form with classical antecedents, it is invariably composed in metrical verse. The lamo kavita , or "long poem," however, is a modern free-verse form that is not divided into chapters and that can address any topic or theme. The longest poetic genre is the mahakavya , the "epic poem," another classical form that must be composed in metrical verse. The importance and popularity of the khanda-kavya and the mahakavya have diminished significantly in the years since 1950.

Some Problems of Translation

All translation involves a loss, whether it be of music and rhythm or subtle nuances of meaning. To translate from one European language into another is no easy task, but when the cultural milieus of the two languages concerned are as different from each other as those of Nepali and English are, the problems can sometimes seem insurmountable. The first priority in translating these poems has been to convey their meaning, tone, and emotional impact. On numerous occasions, I have begun to translate poems that seemed especially important or interesting only to realize that justice simply could not be done to the original and that the task had best be abandoned. Lekhnath's poems in particular, with their dependence on alliteration and meter, are inhospitable territory for the translator: to render them into rhyming couplets would be to trivialize and detract from their seriousness, but a free-verse translation that lacked a distinctive rhythm would be dishonest. For these reasons, Lekhnath is represented here by only a few of his shorter poems: to appreciate fully the elegance of a work such as Reflections on the Seasons , a knowledge of Nepali is essential. In contrast, some of Bhupi Sherchan's compositions lend themselves particularly well to translation, especially to an admirer of Philip Larkin's poems. (See, for example, "A Cruel Blow at Dawn" [Prata: Ek Aghat ].) In every case, I have attempted to produce an English translation that can pass as poetry, without taking too many liberties with the sense of the original poem. I cannot claim perfection for these translations, and it would of course be possible to continue tinkering with them and redrafting them for years to come. Eventually, however, one must decide that few major improvements can be made and that the time has come to publish, although, one hopes, not to await damnation.

The intrinsic difficulty of translating Nepali poetry into English stems partly from some important differences between the two languages. The nature of the Nepali language provides poets with great scope for omitting grammatically dispensable pronouns and suffixes and for devising convoluted syntactic patterns. In some poems, it is impossible for any single line to be translated in isolation: the meaning of each stanza must be rendered prosaically and then reconstituted in a versified form that comes as close as possible to that of the original Nepali. This is partly because Nepali follows the pattern of subject-object-verb and possesses participles and adjectival verb forms for which English has no real equivalents. But the untranslatable character of some Nepali poetry can also be explained in terms of poetic license. Nepali is also capable of extreme brevity: to convey accurately the meaning of a line of only three or four words, a much longer English translation may be necessary.

The translator is often torn between considerations of semantic exactitude and literary elegance. For example, how should one translate the title of Parijat's "Sohorera Jau"? Jau is a simple imperative meaning "go" or "go away," but sohorera is a conjunctive participle that could be translated as "sweeping," "while sweeping," "having swept," or even "sweepingly," none of which lends itself particularly well to a poetic rendering. "Sweep Away" is the closest I have come to a compromise between the exact meaning and the requirements of poetic language. Problems can also arise when poets refer to specific species of animals or plants. This causes no difficulty when such references are to owls or to pine trees, but in many instances one can find no commonly known English name. A botanically correct translation of a verse from Mohan Koirala's "It's a Mineral, the Mind" (Khanij Ho Man ) would read as follows:

I am a Himalayan pencil cedar with countless boughs,

the sayapatri flower which hides a thousand petals,

a pointed branch of the scented Ficus hirta ...

Clearly, such a pedantic rendering would do little justice to the original Nepali poem.

A further problem is caused by the abundance of adjectival synonyms in Nepali, which English cannot reflect. The translator must therefore despair of conveying the textural richness that this abundance of choice imparts to the poetry in its original language. As John Brough points out, Sanskrit has some fifty words for "lotus," but "the English translator has only 'lotus,' and he must make the best of it" (1968, 31). Nepali poets also make innumerable references to characters and events from Hindu, and occasionally Buddhist, mythology and from their own historical past. Nepali folklore and the great Mahabharata epic are inexhaustible sources of stories and parables with which most Nepalis are familiar. A non-Nepali reader will require some explanation of these references if the meaning of the poem is to be comprehended, and brief notes are therefore supplied wherever necessary.

Lekhnath Paudyal (1885-1966)

Lekhnath Paudyal was the founding father of twentieth-century Nepali poetry, but his most important contribution was to the enrichment and refinement of its language rather than to its philosophical breadth. His poems possessed a formal dignity that had been lacking in most earlier works in Nepali; many of them conformed in their outlook with the philosophy of orthodox Vedanta, although others were essentially original in their tone and inspiration. The best of Lekhnath's poems adhered to the old-fashioned conventions of Sanskrit poetics (kavya ) but also hinted at a more spontaneous and emotional spirit. Although often regarded as the first modern Nepali poet, Lekhnath is probably more accurately described as a traditionalist who perfected a classical style of Nepali verse. Note, however, that his poems occasionally made reference to contemporary social and political issues; these were the first glimmerings of the poetic spirit that was to come after him.

Lekhnath was born into a Brahman family in western Nepal in 1885 and received his first lessons from his father. Around the turn of the century, he was sent to the capital to attend a Sanskrit school and thence to the holy city of Banaras, as was customary, to continue his higher education. During his stay in India, his young wife died, and he met with little academic success. Penniless, he embarked on a search for his father's old estate in the Nepalese lowlands, which was ultimately fruitless, and he therefore spent the next few years of his life seeking work in India. In 1909 he returned to Kathmandu, where he entered the employ of Bhim Shamsher, an important member of the ruling Rana family, as priest and tutor. He retained this post for twenty-five years.

As an educated Brahman, Lekhnath was well acquainted with the

classics of Sanskrit literature, from which he drew great inspiration. From an early age, he composed pedantic "riddle-solving" (samasya-purti ) verses, a popular genre adapted from an earlier Sanskrit tradition, and his first published poems appeared in 1904. Two poems published in an Indian Nepali journal, Sundari , in 1906 greatly impressed Ram Mani Acharya Dikshit, the editor of the journal Madhavi , who became the first chair of the Gorkha Bhasha Prakashini Samiti (Gorkha Language Publication Committee) in 1913 and did much to help Lekhnath to establish his reputation as a poet. His first major composition was "Reflections on the Rains" (Varsha Vichara ) and it was first published in Madhavi in 1909. This poem was later expanded and incorporated into Reflections on the Seasons (Ritu Vichara ), completed in 1916 but not published until 1934. More of his early poems also appeared in a collection published in Bombay in 1912.

One of Lekhnath's most popular poems, "A Parrot in a Cage" (Pinjarako Suga ) is usually interpreted as an allegory with a dual meaning: on one level of interpretation, it describes the condition of the soul trapped in the body, a common theme in Hindu devotional verse, but it also bewails the poet's lot as an employee of Bhim Shamsher. Here the parrot, which has to make profound utterances according to its master's whim, is actually the poet himself. This particular poem is extremely famous in Nepal because it is one of the earliest examples of a writer criticizing the Rana families who ruled the country at the time. In terms of literary merit, however, it does not rank especially highly in comparison with Lekhnath's other verse because it suffers from excessive length and frequent repetition. Indeed, some critics regard it as a poem originally written for children.

Lekhnath produced one of his most important contributions to Nepali poetry at quite an early stage of his career: his first khanda-kavya (episodic poem), Reflections on the Seasons , demonstrated a maturity that was without precedent in Nepali poetry. Indeed, it is largely to Lekhnath Paudyal that this genre owes its prestige in Nepali literature. The primary inspiration for this work was probably The Chain of the Seasons (Ritu-Samhara ) by the great fifth-century Sanskrit poet Kalidasa. Each of the six "episodes" of Lekhnath's poem comprises one hundred couplets in the classical anushtup meter and describes one of the six seasons of the Indian year. Most of the metaphors and similes employed in the poem were borrowed directly from Sanskrit conventions for the description of nature (prakriti-varnana ), but a few were unusual for their apparent reference to contemporary political issues:

In the forest depths stands a bare poinsettia

Like India bereft of her strength and wisdom . . .

Soon the flowers seem tired and wan,

sucked dry of all their nectar,

As pale as a backward land

The poem is also often praised for the subtlety of its alliterations and for the dexterity with which Lekhnath constructed internal rhymes:

divya anandako ranga divya-kanti-taranga cha

divya unnatiko dhanga divya sara prasanga cha

Divine the colors of bliss,

divine the ripples of light,

Divine the manner of their progress,

divine the whole occasion

Lekhnath did not develop the great promise of these early episodic poems further until much later in his life, but a large number of his shorter poems continued to appear in a variety of literary journals in both India and Nepal. Many poems were probably never published and may now be lost. A two-volume collection, Delicacy (Lalitya ) was published in 1967-1968 and contained one hundred poems. Lekhnath's shorter works covered a wide variety of topics and conveyed all of the nine rasa . Although many are plainly moralistic, some have a whimsical charm and are often couched in uncharacteristically simple language. One such is "The Chirruping of a Swallow" (Gaunthaliko Chiribiri ), first published in 1935, in which a swallow explains the transient nature of existence to the poet:

You say this house is yours,

I say that it is mine,

To whom in fact does it belong?

Turn your mind to that!

His devotional poems are more formal and are admired for their beauty and for the sincerity of the emotions they express. "Remembering Saraswati" (Saraswati-Smriti ) is the prime illustration of this feature of Lekhnath's poetry. Other compositions, such as "Dawn" (Arunodaya , 1935), represent obscure philosophical abstractions:

Inside the ear, a mellifluous sound

is drawn out in the fifth note,

the more I submerge to look within,

the more I feel a holy mood

Poems such as "Himalaya" (Himal ) are probably intended to arouse patriotic feeling. Lekhnath approached all his work in the deliberate man-

ner of a craftsman, paying meticulous attention to meter, vocabulary, and alliteration. His primary concern was to create "sweetness" in the language of his poems, and many were rewritten several times before the poet was content with them.

In 1951, Lekhnath was invested by King Tribhuvan with the title of kavi shiromani , which literally means "crest-jewel poet" but is generally translated as "poet laureate." Since his death in 1966, no other poet has been similarly honored, so the title would seem to be his in perpetuity. His first composition after 1950 was a long poem entitled "Remembering the Truth of Undying Light" (Amar Jyotiko Satya-Smriti ), which expressed grief over the death of Mahatma Gandhi. Under the censorious rule of the Rana regime, this would probably have been interpreted as an expression of support for the Nepali Congress Party.

The work that is now regarded as Lekhnath's magnum opus is "The Young Ascetic" (Taruna Tapasi ), published in 1953. "The Young Ascetic" is a lengthy narrative poem concerning a poet stricken by grief at the death of his wife, who sits beneath a tree by the wayside. As he mourns alone, a renunciant sadhu appears before him; this man later turns out to be the spirit of the tree beneath which the poet sits. The sadhu delivers a long homily to the mourning poet: as a tree, rooted to one spot, the sadhu has experienced many hardships and has learned much from his observation of the people who have rested in his shade. Thus, after long years of watchfulness and contemplation, he has achieved spiritual enlightenment. The poem contains much that can readily be construed as symbolism, allegory, and even autobiography. The poet probably represents Lekhnath himself, and the descriptions of the changing seasons are said to represent the advent and departure of the various ruling families of Nepal.

Lekhnath was honored by the Nepali literary world on his seventieth birthday in 1955 when he became the focal point of a procession around the streets of Kathmandu. The procession was probably modeled on the old-age initiation ceremony practiced by the Newars of Kathmandu Valley. The old poet was seated in a ceremonial carriage and paraded through the city, pulled by most of the better known poets of the time and even by the prime minister. In 1957, he was awarded membership in the newly founded Royal Nepal Academy, and in 1969 he was honored posthumously with the prestigious Tribhuvan Puraskar prize. These honors are a mark of the peculiar reverence felt by members of the cultural establishment of Nepal for the man whose poems represent the "classical" aspect of their modern literature. He can no longer escape the scorn of the young, however, and he is rarely imitated by aspiring poets. In an essay published in 1945, Devkota defended the "laureate" from his critics:

Whether poetry should be composed in colloquial language or not is still a matter for dispute: we praise the attempts that are made to utilize the melodiousness of rural or mountain dialects, but this, after all, is not our only resort. Even if one agrees that meter can fragment the flow of poetry, it remains true that less criticism can be made of the poet whose feelings emerge in rounded, smooth, illuminated forms than of the poet who expresses himself in an undeveloped torrent of primitivism. (1945, 223)

Surprisingly little is known about the personal life of the man whose poems are now read and learned by every Nepali schoolchild. In the few portraits that exist, Lekhnath, an old man with a long white beard, peers inquisitively at the camera from behind a pair of cheap wire-framed spectacles. Born into a tradition of conservative and priestly scholasticism, he was innovative enough to compose poems in his mother tongue that dared to make occasional references to contemporary social realities, and he also brought the discipline and refinement of ancient Sanskrit conventions to the development of Nepali poetry.

The essential quality of much of Lekhnath's poetry derives mainly from his choice of vocabulary and his use of meter and alliteration; it is therefore rather less amenable to effective translation than the works of most later poets, a fact reflected by the small number of poems translated here. Of these, "A Parrot in a Cage" has been slightly abridged: the Nepali poem contains 25 verses. A translation of Reflections on the Spring , completed some years ago, has with some regrets been deleted from this selection. Many of the one hundred couplets that make up this famous poem are merely exercises in alliteration and rhyme, and as a whole Reflections on the Spring tends to defy translation.

Most of Lekhnath Paudyal's shorter poems are collected in Lalitya (Delicacy), published in two volumes in 1967 and 1968. His longer works —khanda-kavya and mahakavya —are (with dates of first publication) Ritu Vichara (Contemplation of the Seasons, 1916), Buddhi Vinoda (Enjoyments of Wisdom, 1916), Satya-Kali-Samvada (A Dialogue Between the Degenerate Age and the Age of Truth, 1919), Amar Jyotiko Satya-Smriti (Remembering the Truth of Undying Light, 1951), Taruna Tapasi (The Young Ascetic, 1953), and Mero Rama (My God, 1954). Another epic poem, entitled Ganga-Gauri (Goddess of the Ganges), remains unfinished.

A Parrot in a Cage (Pinjarako Suga)

A pitiful, twice-born[1] child called parrot,

I have been trapped in a cage,

[1] Dvija means "twice born" and therefore of Brahman, or possibly Vaishya, caste.

Even in my dreams, Lord Shiva,

I find not a grain of peace or rest.

My brothers, my mother and father,

Dwell in a far forest corner,

To whom can I pour out my anguish,

Lamenting from this cage?

Sometimes I weep and shed my tears,

Sometimes I am like a corpse,

Sometimes I leap about, insane,

Remembering forest joys.

This poor thing which wandered the glades

And ate wild fruits of daily delight

Has been thrust by Fate into a cage;

Destiny, Lord, is strange!

All about me I see only foes,

Nowhere can I find a friend,

What can I do, how shall I escape,

To whom can I unburden my heart?

Sometimes it's cold, sometimes the sun shines,

Sometimes I prattle, sometimes I am still,

I am ruled by the fancies of children,

My fortune is constant change.

For my food I have only third-class rice,

And that does not fill me by half,

I cast a glance at my water pot:

Such comforts! That, too, is dry!

Hoarse my voice, tiresome these bonds,

To have to speak is further torment,

But if I refuse to utter a word,

A stick is brandished, ready to beat me.

One says, "It is a stupid ass!"

Another cries, "See, it refuses to speak!"

A third wants me to utter God's name:

"Atma Ram, speak, speak, say the name!"

Fate, you gave my life to this constraint,

You gave me a voice I am forced to use,

But you gave me only half my needs;

Fate, you are all compassion!

And you gave me faculties both

Of melodious speech and discerning taste,

But what do these obtain for me, save

Confinement, abuse, constant threats?

Jailing me, distressing me,

Are the curious sports Man plays,

What heinous crimes these are,

Deliver me, thou God of pity.

Humanity is all virtue's foe,

Exploiting the good till their hearts are dry,

Why should Man ever be content

Till winged breath itself is snatched away?

While a single man on this earth remains,

Until all men have vanished,

Do not let poor parrots be born,

Oh Lord, please hear my prayer!

(1914/17; from Adhunik Nepali Kavita 1971)

Himalaya (Himal)

A scarf of pure white snow

Hangs down from its head to its feet,

Cascades like strings of pearls

Glisten on its breast,

A net of drizzling cloud

Encircles its waist like a gray woolen shawl:

An astounding sight, still and bright,

Our blessed Himalaya.

Yaks graze fine grass on its steepest slopes,

And muskdeer spread their scent divine,

Each day it receives the sun's first embrace:

A pillar of fortune, deep and still,

Our blessed Himalaya.

It endures the blows of tempest and storm,

And bears the tumult of the rains;

Onto its head it takes the burning sun's harsh fire,

For ages past it has watched over Creation,

And now it stands smiling, an enlightened ascetic,

Our blessed Himalaya.

Land of the Ganga's birth,

Holy Shiva's place of rest,

Gauri's jeweled palace of play,[2] Cruel black Death cannot enter

This still, celestial column,

Our blessed Himalaya.

It nurtures mines of precious gems,

And gives pure water, sweet as nectar,

[2] Gauri is a name of Parvati, spouse of Shiva.

And they say it still contains

Alaka, the Yaksha's capital;[3] Climbing to its peak, one's heart

Is full of thoughts of heaven,

Thus bright with light and wealth,

Our blessed Himalaya.

(from Adhunik Nepali Kavita 1971; also included in Nepali Kavita Sangraha [1973] 1988, vol. 1)

Remembering Saraswati (Saraswati-Smriti

She plays the lute of the tender soul,

Plucking thousands of sweet sounds

With the gentle nails of the mind,

As she sits upon the heart's opened lotus:

May I never forget, for the whole of my life,

The goddess Saraswati.[4]

She wears a crystal necklace

Of clear and lovely shapes,

It refines the practical arts of this world,

And my heart ever fills with her waves of light:

May I never forget, through the whole of my life,

The goddess Saraswati.

She keeps the great book of remembrance,

Recording all things seen, heard, and felt,

All are entered in their fullness,

And nothing is omitted:

May I never forget, through the whole of my life,

The goddess Saraswati.

She rides the quick and magical swan[5] Which dives and plays in our hearts' deep lake,

And she brings to life the world's games and their glory:

May I never forget, through the whole of my life,

The goddess Saraswati.

"When you come to comprehend

The world-pervading sweetness

Of this my art of living,

Your fear and ignorance must surely end."

With this she gestures reassurance:

[3] The Yakshas are attendants to the god of wealth, Kubera, who dwells in the fabulous city of Alaka.

[4] Saraswati, consort of the god Brahma, is patron of the arts and literature.

[5] Each Hindu deity has his or her own "vehicle"; Saraswati is borne by a swan.

May I never forget, through the whole of my life,

The goddess Saraswati.

(from Adhunik Nepali Kavita 1971)

An Ode to Death (Kal Mahima)

It knows naught of mercy, forgiveness, love,

It makes neither promises nor mistakes,

And never is it content,

Indra himself may bow down at its feet,[6] But it heeds not Indra's plea,

It does not pick through the pile,

Dividing sweet from sour,

But checks through all our records;

It never strikes in error.

Kings and paupers are all alike,

It picks them up and bears them away,

Never put off till its stomach is filled;

Medicine's cures present no threat,

Like an undying hunter, it moves unseen.

It bathes in pools of tears,

It dislikes all cool waters,

Without a dry old skeleton

It cannot make its bed,

It wears no more than ashes,

Sings naught but lamentation.

Everything is gulped straight down,

To pause and chew would mean starvation,

All that is swallowed is spewed straight out,

Nothing is digested, through long ages,

Death's hunger never sated.

(from Adhunik Nepali Kavita 1971)

Last Poem (Akhiri Kavita)

God Himself endures this pain,

This body is where He dwells,

By its fall He is surely saddened,

He quietly picks up His things, and goes.

(1965?; from Adhunik Nepali Kavita 1971)

[6] Indra is the mighty Hindu god of war and of the rains.

Balkrishna Sama (1903-1981)

Lekhnath Paudyal, Balkrishna Sama, and Lakshmiprasad Devkota were the three most important Nepali writers of the first half of this century, and their influence is still felt today. Lekhnath strove for classical precision in traditional poetic genres; Devkota's effusive and emotional works provoked a redefinition of the art of poetic composition in Nepali. In contrast to both of these, Balkrishna Sama was essentially an intellectual whose personal values and knowledge of world culture brought austerity and eclecticism to his work. He was also regarded highly for his efforts to simplify and colloquialize the language of Nepali verse.

Sama was born Balkrishna Shamsher Jang Bahadur Rana in 1903. As a member of the ruling family, he naturally enjoyed many privileges: his formative years were spent in sumptuous surroundings, and he received the best education available in Nepal at that time. In 1923 he became a high-ranking army officer, as was customary for the sons of Rana families, but from 1933 onward he was able to dedicate himself wholly to literature because he was made chair of the kingdom's main publishing body, the Nepali Language Publication Committee. He changed his name to Sama , "equal," in 1948 after spending several months in prison for his association with political forces inimical to his family's regime. It is by this pseudonym that he is now usually known. Sama is universally regarded as the greatest Nepali playwright, and it was primarily to drama that he devoted his efforts during the first half of his life. In recognition of his enormous contribution to the enrichment of Nepali literature, he was made a member of the Royal Nepal Academy in 1957, its vice-chancellor in 1968, and a life member after his retirement in 1971.

The young Balkrishna seems to have been unusually gifted because