38—

The Messiah

(1975)

Given his lifelong interest in the probably impossible task of uniting Marx and Jesus, politics and religion, it is fitting that Rossellini's last two major projects concerned biographies of Christ and Karl Marx. Only the first of these, The Messiah , was completed, however, and legal entanglements have kept it from general release for over a decade. This is unfortunate, for though The Messiah is not a flawless film, it is a great one. For one thing, since its subject is usually conceived of in apolitical terms, the inconsistencies of Rossellini's historical method are perhaps less bothersome than they are elsewhere.[1] Furthermore, the director's treatment of the all too familiar story is refreshingly astringent, and the typical strategies of dedramatized acting and antispectacular mise-en-scène here find their perfect subject. Rossellini's interest in the "essential image" also reaches its zenith, resulting in a new emphasis on visual beauty, and Mario Montuori's striking compositions and luminous color photography, coupled with the magnificent Tunisian locations, easily make this Rossellini's most beautifully photographed film.[2]

Different stories are told about how the film came to be made. In some of his interviews (which abound on this film), Rossellini gives the impression that he simply wanted to do a life of Christ and, not finding any backers, went ahead on his own. More likely is the story, reported in Variety and the New York Daily News , of one Father Peyton, an elderly Irish priest who had lived in the United States for many years. Well known for his evangelizing activities on 7radio and television in the late forties and early fifties, Father Peyton is the author of the famous slogan "The family that prays together stays together." According to the Daily News of October 14, 1975, Father Peyton wanted "not just another movie

on Christ, but one that would 'make people love Him,'" and for that he wanted the best filmmaker he could find, "whatever the cost." He asked the advice of "Hollywood Catholics like Mike Frankovich and Gene Kelly and made a special plea to his patroness, the Blessed Virgin. Within 48 hours, he was in the home of Rossellini." (Another version has it that the Virgin appeared to Father Peyton in his sleep and told him to get the "best filmmaker in the world: Roberto Rossellini.") The Daily News story continues: "'I poured out my dream to him,' Peyton recalls in his lilting Irish brogue. 'I said would you be interested? And indeed he was.' . . . It was Rossellini who suggested signing their agreement while before Michelangelo's Pieta [sic ] in St. Peter's Basilica."

Renzo, the director's son, however, has said it was Father Peyton who made the suggestion about the signing, and they decided to humor him.

Father Peyton read the terms of the contract out loud to the Virgin. All the Japanese tourists were wildly photographing this rather bizarre scene. Then Father Peyton got us all to kneel down—it was the first time for me in my adult life—and began praying the rosary. My father and I, terribly embarrassed, mumbled our way through the responses, because we didn't know the correct ones. And thus the ten-page contract was signed in front of the Virgin.[3]

According to Variety (October 15, 1975), the $4.5 million budget, clearly the biggest Rossellini ever had to work with in his entire life, was divided between Family Theater, Father Peyton's group, and Orizzonte 2000, Rossellini's production company. Father Peyton retained the rights in North and South America and wherever English is the principal language, but all other rights were ceded to the director. The Daily News cheerfully reported that Father Peyton would stick to the financial end of things, leaving the creative aspects "entirely to Rossellini." Peyton was predicting that the film would be "beautiful and heartrending," and, the article continued, "Rossellini has earned Peyton's undying respect, as an artist and a man: 'He's a friend of the Lord. He wants this to be the crown of his life' " (p. 52).

Well, hardly undying, for once Father Peyton saw the completed film, the clearly frivolous distinction between the "financial" and the "creative" disintegrated. It was judged to be poorly put together, too long, and too boring; apparently what was especially disappointing, despite the fact that Father Peyton had told Variety that it was not to be a "religious film," was the lack of miracles and the absence of God's voice at the appropriate moments. The De Rance Corporation of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, a Catholic distribution company associated with Father Peyton, refused to allow the film to be shown anywhere in North or South America. When critic Eric Sherman, on the selection board for the Los Angeles-based Filmex festival, tried to screen Rossellini's version of the picture in 1978, the De Rance Corporation got a restraining order, claiming that they wanted to cut thirty minutes of the film, rearrange the scenes, and add a voice-of-God narration. According to Sherman, they also persuaded Thomas McGowan, one of the makers of Born Free , to sign an affidavit attesting that Rossellini's version would definitely be reviewed negatively and would therefore endanger

De Rance's $1.5 million investment in the film.[4] (McGowan told Variety [May 3, 1978] only that he had been hired to "perfect the English language version," the cost of which he estimated at another $100,000.) Suits and countersuits were filed, and the film, apart from scattered showings of the Rossellini family's print at college campuses and elsewhere, has yet to be released in the United States.

Many of the trademarks of Rossellini's historical period are in evidence, though the luxury of a larger budget results in a definite shift of technique. Among the typical emphases we find a desire to give us a "real-life" Christ, one who was familiar with work. (Rossellini even has him deliver one of his sermons while doing some carpentry.) In the interests of historical documentation, we are shown a perhaps overly graphic display of Jewish sacrificial slaughter. The handclapping game played by the little boys, which is actually Tunisian, feels authentic even if it is not. Similarly, we see fishermen casting nets, Mary making bread, and other constant emphases on the unspectacular events and activities of daily life. Much of this quotidian imagery derives almost directly from Acts of the Apostles (1969), as does the film's emphasis on community, and just as in that earlier film, the miraculous and the spectacular are indeed decidedly muted. For example, the scene of Christ walking on the water is omitted, as is the usually mandatory and highly emotional via crucis , Christ's carrying his cross to the site of his crucifixion on Golgotha. For Rossellini, including the latter scene would have been not only too dramatic, but also inessential when compared with Christ's words.

In an interview with the editors of Filmcritica , Rossellini elevated this antispectacular technique almost into a metaphysics, saying that he wanted

a reconstruction of everyday life, of the most normal data, and then to set the event in this context. Everything then becomes extremely simple. . . . This data is the reality on which everything is based. All the parables, even though they have an abstract meaning, aren't really abstract in the least; they all refer to the small facts of everyday life, the facts that we have lost, that we no longer know.[5]

He goes on to link this concretization with the aesthetics of the zoom itself, which is able to "furnish a great quantity of contextual data." By means of what is perhaps a less than innocent subjectivist misreading of Marx, he even claims for the long take and zoom a special neutrality, beyond that of the regular shot, that it obviously cannot have:

Marx once said a beautiful thing: "The concrete is the synthesis of many determinations." If you want to get to the concrete, you must present a quantity of determinations which everyone can synthesize according to his own personality, his own nature. The plan-séquence allows me to present all this data, without falling into the "privileged" point of view of the fixed shot (pp. 126–27).

Matching this typical dedramatized presentation of "facts" is Rossellini's portrayal of a Christ who is, unsurprisingly, a thinking Christ, a humanist Christ (Rossellini told one interviewer that he saw Christ as "the perfect man," rather than as God). Accordingly, the director accentuates Christ's loving, human side

and pays little attention to the divine, especially as it might be revealed in miracles. A remark he made to the interviewer for Écran sums up his attitude perfectly: "Can you imagine, in order to think of Christ as a great man—or a great God, if you prefer—they had to add miracles! When actually the guy who said 'the Sabbath was made for man, and not man for the Sabbath' was making a political statement of fundamental importance."[6]

Rossellini's Christ is the logocentric Christ incarnate in the Word of the Gospels, and thus, again, the director does not attempt to "capture" the period itself, but rather to adapt the Gospels, the already clearly mediated contemporary report of that period. Rossellini, in fact, insisted on his fidelity to the Gospels, claiming to have "put Jesus' words in the foreground."[7] The viewer also comes to re-appreciate in this context Rossellini's inclusion of temps mort: when "nothing happens" on the screen, one is forced to attend, perhaps for the first time, to what the familiar words actually mean and what they might have meant within the social and religious context of the era. Rossellini's displacement of some of Christ's words to the apostles and disciples who surround him is further evidence that, as Claudio Sorgi has pointed out in an excellent essay, "the true protagonist of the entire film is the Word of Jesus, as the penetrating, clear, incontestable realization of the ancient word. A word that is received by the disciples, taken up, and amplified."[8] It should also be pointed out that Rossellini's insistence on the actual "real" words of the Bible whenever possible paradoxically almost guarantees the artificiality and stiffness—the lack of "realism"—that many have complained about in this film. The words of the Bible are written words, after all, and will never sound like actual speech. The result of this strict adherence to biblical language is a further self-reflexive distancing that accords well with the film's general strategy of dedramatization.

What also interests Rossellini about the Word is its relation to law, just as we saw in Acts of the Apostles . In fact, Christ sees his principal role, as did the apostles in the earlier film, as providing a reinterpretation of the law. Similarly, we are encouraged to understand Christ in terms of Jewish customs, and in one scene, Mary carefully rehearses these traditions for the child Jesus. The director especially stresses the tradition of messianism (as is evident in the film's title), exploring its sources by opening the film in 1050 B.C., far earlier than most conventional depictions. With the larger budget, the magnificent zoom now moves through an entire desert, onto a small nomadic tribe, situating it in its geographical and historical context (a thematically important shot whose effect would have been greatly decreased on a television screen; in spite of what Rossellini says in interviews, in other words, the increased financial backing is making the director think more "cinematically"). The dialogue that ensues explains the roots of messianism, the longing of a people for the "king who will bring justice." Throughout the film we are given much more information about Jewish history than is usual, and we come to share the Jews' burning desire to be free from Roman domination and their fear of being destroyed as a race. Though some have suggested that The Messiah , like Acts of the Apostles , is anti-Semitic in tone (which is, strictly speaking, unavoidable if one faithfully follows the New Testament), this is, in fact, the first film on the life of Jesus to treat seriously and in any real depth the Jewish tradition from which Christ sprang. Throughout,

the Jews' motives are always seen as historically complex, and their rejection of Christ, at least from their point of view, completely justifiable.

Christ's life, furthermore, is placed firmly within this context. In the depiction of his early years, for example, he and his family are seen almost exclusively as members of a community; he is little more than another boy among many. Rossellini's penchant for radical understatement works perfectly in this regard, revitalizing tired views of overfamiliar events by purposely making them mundane. The Nativity happens in seconds, nearly in the dark, in an out-of-the-way corner. Like Louis XIV and Pascal, Christ must struggle to win his right to the center of the screen; even after screen has been conquered, however, the Beatitudes are delivered as quickly and in as unemphasized a fashion as Lincoln's Gettysburg Address. At the end, Auden's poem "Musée des Beaux-Arts" comes to mind, as the children continue to play and sing songs while a man named Jesus Christ, completely unnoticed by all but his family and friends, dies on the cross.

Similarly, the crowd scenes are decidedly un-deMillean, and no miracles are directly portrayed, though some are presented to us by ellipsis (for example, the enormous catch of fish and the later multiplication of the loaves and the fishes) and we hear of others. Thus Rossellini is not purposely negating a divine side of Christ (presumably verified by such miracles), as some Catholics critics have alleged, but is simply attempting to despectacularize his life. To viewers not accustomed to Rossellini's severely understated style, this minimalism can be disappointing. Nevertheless, the brilliance of the director's choices come to be appreciated on subsequent viewings of the film. For one thing, Rossellini assumes and even plays against what the spectator already knows (and thus the dynamic here is much different than in the other historical films); the effect is not unlike some recent productions of Shakespeare's best-known plays. Familiar scenes like the Nativity and the Crucifixion actually become notations, almost signs of the idea of the events rather than a realistic representation of the events themselves. Yet their very minimalism makes them somehow even more resonant and iconographically powerful. The Sermon on the Mount is so utterly denuded that it even comes dangerously close to becoming a visual joke: Christ steps up on a minuscule hillock, hardly more than a bump, and delivers the Beatitudes in about thirty seconds. Yet it works. Similarly, the scene at the manager is desolate, and thus feels right, and the entire scene of the Last Supper is filmed in complete silence—no words and no music—and is perhaps the most powerful version of that event ever filmed. This minimalist mise-en-scène also becomes starkly symbolic at times, as when Christ, like Socrates, is associated with the blinding light of the exteriors, and the Pharisees who seek his downfall, with the darkness of the inside.

Rossellini's technique, as mentioned earlier, is also modified in this film due to the amelioration of the usual financial difficulties. Hence, The Messiah includes many more cuts, which increase postproduction costs; obviously thinking of Rossellini's use of the zoom in a solely aesthetic way can be misleading. As Renzo Rossellini insisted quite strongly to me, the zoom and the long take were used in the earlier historical films because they were infinitely faster and therefore infinitely cheaper. (In addition to the savings brought about by the long take in the editing process, lighting and camera setups had to be done only once

for each scene, and thus a much smaller crew was required.) Of course, this does not mean that the zoom does not have any aesthetic effects, only that its use was often dictated by the most banal considerations.

The increased cutting and the greatly enlarged number of scenes (some eighty or ninety) also make The Messiah move much faster and thus seem less ponderous than some of the other history films, especially in terms of the long speeches. (Yet now a new problem arises, for the quick cuts sometimes sententiously underline what Christ says as unsubtly as if his words were accompanied by great blasts of Hollywood-style music.) Camera movement increases as well, and we are treated to many circular turns reminiscent of films like Germany, Year Zero and Fear . Now, however, the tight, claustrophobic circles of those earlier films expand to the wider circles of the apostles and Christ, which visually replicate their communal togetherness, and to the even larger circles that suggest the historical unity of an entire race. As in Vanina Vanini , Rossellini's lyrical camera movements in this film become positively Ophülsian.

The zoom, however, is by no means forgotten, and in fact is the principal means by which the film is organized spatially. Yet in this film—especially in extreme long shots, as in the shot at the very beginning of the film, mentioned earlier—the zoom now seems to flatten out perspective, to insist more strongly than ever on the two-dimensionality of the screen image. Most theorists consider this to be the usual effect of the zoom, but, as we have seen, Rossellini often counters this tendency by arranging groups and objects in semicircles that the zoom then penetrates optically, at least, to give an impression of depth and three-dimensionality. Here, however, because the vast majority of the shots are exteriors, and in enormous spaces, this effect of spatial penetration is lacking. The result of this flattening is to insist, in a stronger way than ever before, on the painterliness of Rossellini's compositions, and to suggest self-reflexively, once again, the sources of his iconography and even his choice of events to dramatize, since the visual traditions of Western art had long isolated certain "photogenic" events for treatment. A scene like Christ driving the money changers from the temple, for example, seems clearly based on late Renaissance prototypes, specifically Titian and Tintoretto.[9]

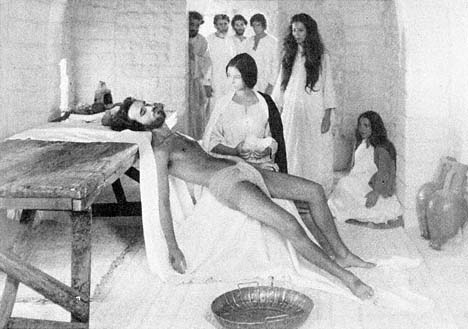

The most stunning iconographic aspect of the film, and one that has surely struck every viewer the film has ever had, is the depiction of Mary, throughout the film, as a very young woman, even an adolescent. Played by Mita Ungaro, a Roman woman who at the time of the filming was only seventeen years old, the youthful Mary blends quite easily into the narrative in the beginning of the film. By the time of Christ's death at age thirty-three, however, her youthfulness does not realistically work at all and is, in fact, quite jarring. At one point Rossellini overtly emphasizes the enigma he has created and provides its solution at the same time. This comes during what is perhaps the most visually powerful moment of the whole film: Christ has been taken down from the cross and laid on the lap of his mother, and together they form a superbly beautiful Pietà, a direct quotation of Michelangelo's famous work. The suffering, if exquisitely beautiful, Mary has the enormously long body of Christ draped across her, in a raw and courageously lengthy shot that comes close to being blatantly sexual. (Claudio Sorgi speaks of Michelangelo's marble having become flesh in Rossel-

Rossellini's Pietà in The Messiah (1975). (Pier Maria Rossi and Mita Ungaro.)

lini's film, and this effect is heightened by the slow zoom through or past this "icon" onto the watching men behind, perhaps the strongest effect of depth in the film.) The iconography also points to the source of Mary's youthful looks, for Michelangelo chose to make Mary as young as or younger than her son in his magnificent sculpture, and Rossellini is following the sculptor's icongraphic choice to the letter.[10] Another possible source for Rossellini's choice—and apparently Michelangelo's—is Dante, who in canto 33 of his Paradiso refers to Mary as "Vergine madre, figlia del tuo figlio" (Virgin mother, daughter of your son).[11]

The effect of Mary's youthfulness, in any case, is to disturb the surface realism of the film text and, like the minimalist mise-en-scène and the biblical language, to foreground its artificiality. The French critic Jacques Grant has even argued that Mary's youthfulness is a self-conscious Hollywood image, which Rossellini uses as "a moving counterpoint, upsetting and malicious, to the essence that he is looking for in the events,"[12] but this seems an idiosyncratic view. On the contrary, Mary is clearly at the heart of The Messiah and, as Mireille Latil Le Dantec has pointed out, all its feeling resides in her, for her physical and emotional trajectory is what organizes and leads us, by means of the camera that follows her, through the film.[13] She even seems to stand in for Christ during the missing via crucis: hearing of her son's being taken to Golgotha, she rushes off to be with him, falling twice in the process. One would be hard pressed to say if this was intentional or not on the director's part, but he did not reshoot the scene because of "mistakes."

One item that remains to be discussed is just how religious this film is. Many Catholic writers have claimed Rossellini for their own throughout his career, but in spite of his often overt religiosity, he has almost perversely refused to join their cause. The following exchange elicited by Jacques Grant at the end of 1975 is instructive in this regard:

Q: So you began The Messiah at a historic moment of rupture, of confrontation?

A: It's Jesus, the history of Jesus, that's all. I made The Messiah with a great deal of respect for everyone. What is great in Jesus's message is his faith in man. That is what is irreplaceable, even though I am a complete atheist.

Q: People usually think just the opposite.

A: Everyone is permitted to fool himself however he wants. If someone just wants to place me, he can always say that I am a Christian without knowing it. But one can also perhaps place oneself, and ask why one is interpreting incorrectly.[14]

In another interview Rossellini says, "I'm not religious at all. I'm the product of a society that is religious among other things, and I deal with religion as a reality."[15] But if Rossellini is uninterested in Christ as God, he is very taken, indeed, with his life and teachings. Thus, he says elsewhere of The Messiah , "I always thought that this would have to be the point of arrival. In my maniacal search for an abcedarium of wisdom I had to put down so many letters to reach, sooner or later, the highest point, the compendium of everything."[16]

This kind of sentiment was unfortunately not enough to endear the film to most religious people, however, who have generally not liked it because it is not "religious" (that is, dramatic and emotional) enough. On the other hand, political critics have opposed it because, as Lino Miccichè has somewhat unfairly insisted, it dehistoricizes Christ's message and thus "loses sight of its subversive value."[17] Once again, Rossellini occupies an awkward and hopeless position between two camps: in fact, he was unable to find a distributor for the film at first, even in Italy, and he complained bitterly about this fact in an article entitled "E reazionario parlare di Gesù?" (Is It Reactionary to Speak of Jesus?) published in the Communist-leaning daily Paese Sera on May 8, 1976. In the article he attacked the revolutionary Left, the conventional film industry, and those who wanted to be "cultural" but had old-fashioned ideas of what that meant: for him, this unlikely combination had insured the film's failure. Ultimately, Rossellini did find a distributor, but The Messiah has been seen by only a few, even on the Continent. It is to be hoped that this superb film, in many ways the climax of Rossellini's career, will be released in the English-speaking world one day—in the state in which he left it—by those whose religious vision seems so impoverished when compared with that of this self-styled atheist.