37—

Anno Uno

(1974)

What Renzo Rossellini calls un anno vuoto (an empty year) followed the making of Cartesius , perhaps the most rigorous and methodologically uncompromising film of Rossellini's career. The reaction against it was so severe that the director lost even the tenuous connection he had maintained for ten years with the RAI-TV. According to his son, as soon as one film was finished, there had always been another one already in the preproduction phase. But not this time. Instead, he had to take what he could get: "The level of my father's prostitution coincided with financial need, and Anno uno came at the lowest point. After the films on Pascal and Descartes and the others, his reputation was at rock bottom; the public hated them, as well as the critics. At this point he was approached by the Christian Democrats, and he had to make this film out of economic necessity."[1]

The project was to make an "unbiased" film on the life of Alcide De Gasperi, the Christian Democrat politician who was the first prime minister of Italy following World War II, on the occasion of the twentieth anniversary of his death. Destined from the first for theatrical release, the film was produced by Rusconi Film, in the person of Edilio Rusconi, known for his right-wing views. According to Variety , the unknown Leandro Castellani was originally scheduled to direct the film, but Rusconi was finally persuaded by Amintore Fanfani, probably the most powerful man in the Christian Democrat party, to give the job to Rossellini.[2] What was especially annoying to leftists was that $1 million of the film's $1.3 million budget was guaranteed by the supposedly nonpartisan Italian state film distribution agency, Italnoleggio.

Many years earlier, in 1949, Rossellini had told an interviewer from the New

York Herald Tribune that, above all, he would not film the struggle going on between communism and democracy in his country: "There is a fight going on there between the two factions, it is true, but it is not dramatic." Strange words for Rossellini but, in any case, dramatic or not, financial exigency and the passage of time apparently convinced him of the wisdom of a return to this area of his former success (to which he had already unwillingly returned once before, in 1959–60, with General della Rovere and Era notte a Roma ). The new film's working title was Anni caldi (Years of Tension—literally, The Hot Years), and the fact that it was changed to Italia: Anno uno (Italy: Year One)—subsequently shortened to Anno uno —indicates both a desire to give the project a more "constructive" tone and to allude to Rossellini's Germany, Year Zero of twenty-five years before, and thus retrospectively to take on the aura of the early films. Variety also reported that the film was to open with the final frames of Paisan , but, in spite of the fact that the film begins with the Resistance, this idea was dropped.

It should be mentioned at this point that Rossellini's vaunted "return to cinema," inaugurated by this film, was really no such thing at all. In fact, the director explicitly stated at the time, "My new film is exactly the same as the ones made for television,"[3] and the technique of Anno uno is virtually identical to that of the other history films. The long take employed in conjunction with the Pancinor zoom is the basic unit, as usual, and the editing remains unchanged, as does the method of conveying background information. Alcide De Gasperi is played in the usual severely understated fashion by Luigi Vannucchi who, in Philip Strick's apt formulation, "merges so self-effacingly with his environment as to become almost invisible in rooms occupied by more than two people."[4] Throughout, the color is characteristically rich and saturated, and Rossellini continues to organize his mise-en-scène around tables or semicircular groups of men, which establish an inner space through which the Pancinor zoom can move. (In one scene, located in a restaurant, the director overcomes the problem of cramped space by placing the group in front of a huge mirror, thus creating a similar sense of three-dimensionality.) In other scenes Rossellini uses his standard choreographic technique of walking groups, which provides exposition while simultaneously leading the camera to discover other groups on whom it lingers momentarily, before moving again. Anno uno also has the same editor, music composer, cinematographer, and screenwriters as Rossellini's previous film, Cartesius . Therefore, this film and the next, The Messiah , though not technically made for television, can be included under this rubric. It must also be said, however, that while technique remains unchanged, the intellectual ambitions of this film are much more modest than those of the earlier history films, and subtlety is not its strong suit. Early on, for example, there is a resonant image of Socialists and Christian Democrats driving around a statue of Garibaldi, the father of Italian unity—resulting in a subtle, almost subliminal, sense of wish fulfillment. The thematic effect of the shot is diminished, however, when the camera pans back toward the statue after the car has passed, and then zooms in. Passersby also make appropriate comments linking Italy's past and present, just in case anybody in the audience has missed the point.

Italian history of the period, unsurprisingly, is considered as being more or

less synonymous with De Gasperi's aspirations and dreams for a united Italy; once again, Rossellini's concern for unity is paramount. The film opens with Resistance activities against the Nazis and Fascists in 1944, specifically the famous bombing in Rome's Via Rasella, which the Nazis answered by killing over three hundred Italians in the caves of the Fosse Ardeatine; this event epitomizes the horror of the German occupation, and has been alluded to in every Rossellini film set in that period. What follows are the immediate postwar manipulations of the various parties to tame the popular leader of the Resistance, Ferruccio Parri, and take political control themselves. Accompanying the depiction of these events are many external shots of Rome, which serve primarily as visual relief from the many unavoidably static internal scenes of discussion, but which also recall the importance of this particular city in Rossellini's career. The referendum of 1946, in which Italy passed from monarchy to republic, is followed by the decisive election of 1948, in which the Christian Democrats virtually take complete control of the government. Next comes the attempt on the life of the Communist leader Togliatti, which provokes vast protests all over Italy, but De Gasperi, through his alliances with minor parties (which has been the Christian Democrat strategy ever since), rides out this storm as well. In fact, we are made to feel quite sorry for the prime minister as he is booed by Communist crowds. Throughout, we see him working closely with the Americans, especially to keep the Communists out of government, but at the same we are led to understand that his own sympathies are principally liberal, even leftist. Thus, he works hard for European unity and shows great sympathy with the problems of the south.[5] His principal difficulties are shown to come from the right-wing of his party, which, in tandem with the Vatican, presses for an alliance with the neo-Fascists rather than allowing the Communists any power whatsoever. Perhaps his least sympathetic moment comes in 1953, when he attempts to push through Parliament what Italians called the legge-truffa (trick law), which would have given control of the government to the party with the greatest number of votes (even thirty percent, say), thus eliminating the need to form coalitions. His strategy fails, and a year later, the party shunts him aside in an emotional moment at their national convention in Naples. Quite uncharacteristically for Rossellini, the film turns rather sentimental at the end, as De Gasperi returns to his home town in the north, to die a few months later.

By this point in the director's life, despite the fact that his financial and critical failures far outweighed his successes, Rossellini's name carried immense prestige in Italy. He had been there at the beginning, after all, chronicling his country's rise from fascism and the destruction caused by the war. Thus, when the world premiere of Anno uno was held at the Teatro Fiamma in Rome on November 27, 1974, everybody who was anybody in Italian political life was present, causing editorialists to complain the following day about the stupidity of virtually the entire government gathering in one spot during this period of increasing terrorism. The president of the republic Leone came, as well as Prime Minister Mario Rumor and nearly all the heads of the various ministries. The leaders of all the major political parties were also crowded in together, including Fanfani of the Christian Democrats, Enrico Berlinguer of the Communists (who had to sit on the floor), and Giorgio La Malfa, the Republicans' chief.

No one came out of the screening happy, however, as Rossellini had once again managed to alienate everybody. Some of the negative reaction was of a piece with that occasioned by all of Rossellini's historical films: thus, the reviewer for Variety derided the "endless wordstream" that drowned out any visual interest the film might have, as well as the detached and expressionless acting (though he did admit that the original plan to star Gregory Peck in the lead role might have made things even worse). But the political reaction was even more severe. Giorgio La Malfa walked out during the intermission of the premiere, complaining of the film's "historical inaccuracies." Italian newspaper reviews, according to Variety , ranged from "bad to cruel," but the director's response was that Open City had also been panned when it was first shown, and ultimately the same success would come to Anno uno . (That success had not yet come five years later, for when I first saw the film in the summer of 1979, a violent shouting match erupted in the theater, with young people openly hissing De Gasperi's various pronouncements throughout the film.) No political party liked the portrait that Rossellini had painted, not even the Christian Democrats who had commissioned the film. Most upset, however, were the Communists, given the fact that the entire film is a chronicle of De Gasperi's success at installing the Christian Democrats in power and keeping the Communists definitively out (a situation that remains unchanged nearly forty years later). Rossellini was called a "servant of the regime," to which charge he responded angrily, "Only someone who delights in being servile could imagine somebody acting solely to make everybody happy."[6]

Rossellini's sister, one of the scriptwriters of the film, defends its anticommunism on the grounds that the Communists of the period were Stalinists, and had to be neutralized so as to prevent a totalitarian revolution. His son Renzo's interpretation is more complicated. According to him, if seen in its proper historical sequence (the director, in fact, insisted in his last years that his films should be seen in the chronological order of their subjects , not according to when they were made)—that is, after Paisan and before Europa '51 —"this film would explain better than anything else why the little boy [of Europa '51 ] kills himself and why the mother ends up in the insane asylum. This film shows how the best hopes and aspirations for the postwar period were killed by the thousand manipulations of the politicians." Renzo even insists that, in spite of the fact that the film was virtually paid for by the Christian Democrats (who had placed a censor on the set whom Rossellini won over by letting him play with the equipment), it actually presents De Gasperi negatively. Or at least De Gasperi is seen using the hopes and support of the little people all over Italy as a form of currency in political exchange, taking his orders from Washington to put the Communists out of the majority, and so on. In Stromboli and other films, according to Renzo, we see the psychological and spiritual results of this kind of cynical manipulation. It is in this sense that, for Renzo Rossellini at least, Anno uno has "a tragic and emblematic value."[7]

This argument has its merits, but it cannot stand up to the experience of watching the film. For, throughout, De Gasperi is clearly seen in a quasiheroic light; rising above the petty politics in which lesser men are mired, he takes an only slightly less exalted place alongside Rossellini's other historical figures like

Socrates and Christ. Rossellini, as usual, insisted that he was merely presenting neutral, historical information without trying to interpret, telling Claude Beylie in 1975, "It's not a political film, it's a film about politics" (as if the two could be so neatly distinguished). He also gave a clear sign of his ongoing frustration: "Naturally, it was greeted in Italy with scorn. I was dragged in the mud once again. Since I refuse to serve the politics of the moment, there was a cabal against me."[8] To an Italian audience, he said:

This film on Italian life from 1944 to 1954 allows me to remain consistent with my principles and with that work of providing historical information that I began ten years ago on television. This film departs from the usual paths in which cinema has become fossilized. I was given the opportunity to make an educational work which would reduce the horizons of our ignorance. It seemed very useful to me to look carefully once again at what happened in those years when we were in the midst of complete ruin. We can still learn a lesson from it.[9]

Beyond the new urgency to relate the film's themes to the specific political situation of the mid-seventies, the words are calm, measured, almost Olympian: the reduction of the horizon of ignorance requires only close attention to the facts. We have already seen in the other historical films that such an "objective" presentation is always impossible. What is especially noteworthy about Anno uno , however, is that by taking on a more or less contemporary subject, the inconsistencies of Rossellini's historical method are plainly revealed. Though he is making the same kind of film, with the same assumptions, we are no longer dealing with historically sanctified figures like Socrates and Pascal, in whom viewers have little personal, emotional stake and about whom they have very little information before seeing the film. With De Gasperi, all this changes; not only does every Italian, depending on his or her political affiliation, have a version of what actually happened during the ten-year period covered in the film, but many of its participants were still alive (and many of the men depicted in the film were sitting in the audience during its world premiere).

And the political battles over Rossellini, more or less dormant through the period of the historical films (once having objected fundamentally to Rossellini's method of studying history, what else was there for Marxist critics to say about each film as it appeared?), were reignited, first in the pages of the country's newspapers and then in somewhat more considered form in its film journals. Tullio Kezich, for example, an important leftist newspaper reviewer, called Anno uno a "pathetic attempt to contribute to the foundation of a Christian Democratic political culture."[10] The special problem for film journals, however, whether Catholic, modernist, or Communist, was that even within a journal opinions were mixed, and this much at least must be said for Rossellini's attempt to be neutral: there is barely a political position that one can take on this film that, looking at other evidence, cannot be easily reversed. Typical was the situation of the editors of the liberal Catholic journal Rivista del cinematografo , who, unable to decide what they thought of the film, ran two opposing articles, one strongly in favor, the other as much against. (Though these contrasting positions occurred in the context of a great and continuing admiration for Rossel-

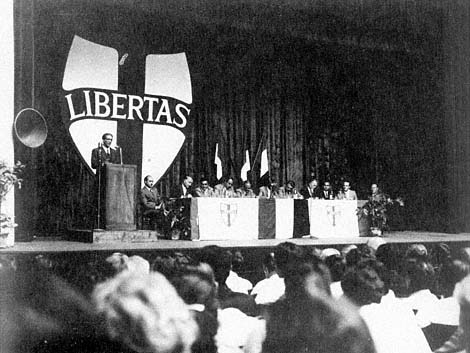

The problematic history of the present: Alcide De Gasperi (Luigi Vannucchi)

speaks at a Christian Democrat party meeting in Anno uno (1974).

lini, whom the editors mention alongside De Gasperi as "two of the most important names in the last thirty years of Italian history.")[11] For the Communist Cinema nuovo , the film "unintentionally describes with crude realism the collapse of a myth, that is, the myth of Rossellini as eternal master and greatest author of neorealism." Furthermore, the film is seen as one more example of the current "fascination for fascism": "It celebrates the death of cinema and of conscience and of every progressive ideology." This critic also attacks the film for seeing history as the "product of the attitudes of political 'personalities.'"[12] He is right here, for while Rossellini clearly wants to make a film on De Gasperi's ideas, the figure himself cannot help but become valorized and even heroic in the process. After all, in a film that is more or less conventionally structured in narrative terms, ideas can be embodied only through personalities, and this embodiment can never be an innocent act. Thus, the American critic Tag Gallagher misses the point, I think, when he naively echoes Rossellini's view that this film should be considered a film on politics, rather than a political film: for him, Rossellini "holds up an idealized political theory and method as a model for his nation (and the world) today."[13] When "an idealized political theory" is put in the mouth of a specific politician, from a specific party, during a specific period, however, it always inevitably becomes something else.

Perhaps the most sophisticated attack on the film is the article by Sandro Zambetti published in Cineforum .[14] His initial complaint is that, since everything is seen from De Gasperi's perspective, much more information should have been provided to contextualize the events; newspaper headlines and small groups of politicians acting as De Gasperi's straight men are simply not enough. His principal criticism, however, is that Rossellini fails in his attempt to go beyond the standard methods of teaching history to the young, or the picture books published on important historical figures. As usual, Rossellini is presenting a specific point of view, in this case, "that of the De Gasperi centrism as democratic and secular choice, a firm rejection of fascism, but also a dignified resistance to any sort of religious collusion, a vigilant opposition to every attempt of the left to move the balance of power from the parliament to the streets, but also a noble opening to the social petitions of the country" (p. 22).

This is Rossellini's view of De Gasperi's politics, and it is also the historical view of itself that the Christian Democrat party has always fostered, even up to the present day—the middle road between the "two extremisms." Zambetti's telling critique is that this nonposition has served merely to fill a lack of any real Christian Democratic philosophy. The leading members of the party are right to insist that they are De Gasperi's heirs, since they have added nothing to his views; their continual urge to present themselves as the "party of the center" is meant to disguise what they have always been from the beginning, and continue to be: "the only right-wing politics possible in Italy, conservatism cloaked in moderation and with a touch of reformist cosmetics" (p. 23).

By making this film from their point of view, Zambetti continues, Rossellini is guilty of continuing to promote this image of the Christian Democrats:

Next to the democratic De Gasperi, who refuses to exploit to its limits the absolute majority of the April 18 [, 1948,] election, preferring instead to rely on the collaboration with the other centrist parties, what is lacking is the De Gasperi of the "trick law." Or rather, he is there, but justified by the Jesuitical line of one of his party colleagues ("It's not a trick law: if the left would have won, they would have taken advantage of it too" as if the law had not been specifically written to exclude such a possibility). (p. 24)

We see the De Gasperi who wants to limit the power of the Vatican over the party, insisting on the party's laicism, but we do not see the De Gasperi who depended so heavily on the clergy's harangues from the pulpit to convince the people to give the Christian Democrats their overwhelming majority on April 18. We see the De Gasperi tortured by the problems of the south, but not the De Gasperi who does nothing about them. And so on.

According to Zambetti, the director resolves all of these problems by giving us a good man , over and over, a man weighed down by the incredible tasks that are continually thrust upon him. "At the center of the stage there is not a statesman and a politician, but a good man who, by chance, heads the government and guides a party." Rossellini shows the "suffering of power" that is part of the traditional baggage of the saintly figure:

An anthology of virtues, in short, which we will not call into doubt, but of which it is necessary to say that it serves once more to displace the discourse

from the political level to the moral level, asking the spectator to become aware not so much of the political acts of the protagonist, but of the good intentions with which he has undertaken them and the principles which have inspired him, all the things which transform ten years of history which we should be concerned about into ten years of spiritual exercises. And which, above all, remove the politics of the Christian Democrats from debate, guaranteeing them in advance with the little flowers of De Gasperi. (p. 25)[15]

This time, then, history was simply too close. Its recalcitrant and disjunctive particulars had not yet been sufficiently forgotten or repressed, as they had been in all the other films of this period, to allow Rossellini to work his essentialist magic.