V—

THE GRAND HISTORICAL PROJECT

27—

Introduction to the History Films

"Illibatezza" closes a certain chapter in Rossellini's career; apart from the last two films he ever made, Anno uno and The Messiah —which, though intended for theatrical release and shot in a wide-screen format, do not differ essentially from the previous decade's work for television—he was never to return to the commercial cinema. His always minimal interest in telling a "good story" is now gone completely, and his first priority becomes the production of information to aid human beings in becoming more rational, an impulse already at work as early as India .

Rossellini will now expunge whatever remains in him of the mystical and the spiritual in favor of the reconstruction of history. In the facilely symbolic terms mentioned earlier, it could be said that he once and for all leaves the Franciscan Middle Ages for the world of the Renaissance where, in theory at least, reason is king. It is therefore no coincidence that one of the major achievements of this period is the three-part series on the Age of the Medici. Even the historical films concerning other eras are informed by a cool Renaissance rationality that assumes a discoverable order in the universe, a cosmos in which all is inevitably centered on human beings and their ability to make sense of things and, in so doing, to master their world.

Unfortunately, it will not be possible to provide close readings of all the didactic films, principally because of their sheer massiveness: L'età del ferro is five hours long, La lotta dell'uomo per la sua sopravvivenza , twelve, Acts of the Apostles , six, and so on. In the face of this immense output, one can only hope to sketch out a general project and a particular way of seeing history and humankind. Another factor is that after Acts of the Apostles (1969) Rossellini's

style or technique, his way of organizing his material, does not substantially change. There is some experimentation in the beginning—L'età del ferro , for example, is part documentary and part fiction film, set both in the past and in the present—but with the universally admired La Prise de pouvoir par Louis XIV (1966), Rossellini seems to have settled definitively on the format of the "great man" who is examined as a representative of his age, usually an age in which, according to the director, some profound change occurred in the history of human consciousness. The purpose of the present chapter, therefore, will be to discuss what these films have in common; differences will be left for later.

What also becomes important in this period are the director's writings, which include a great many articles, two books, and an enormous number of interviews (which were, for Rossellini, another form of writing, another way to get his message across). In the 1962 interview with the editors of Cahiers du cinéma , Rossellini, at the lowest point in his creative life, seems to have considered giving up film altogether since it "is incapable of establishing general ideas and discussing them because it is too expensive." He is convinced, at this moment at least, that "the book is still the basis of everything." Since he has nothing left to say with film, he will begin writing essays, no matter how difficult it is, as a way to engage "the world, in order to be able to study it, to understand it."[1] A short time later, of course, Rossellini will find the perfect medium—the didactic, essayistic film made for television—and his interest in the cinema will be reawakened. But it will be a cinema of an altogether different sort.

One of the earliest statements of his changing ideas comes in a 1959 open letter to the new minister of culture, Signor Tupini. In it Rossellini poses the basic question: "Will the cinema be considered on the level of art and culture or as a means of squalid escapism and the infantilizing of the public on the same level as television, for which the government is seriously responsible?" (This clear-cut placement of film, art, and culture on one side and an "infantilizing" television on the other will soon be modified.)[2] In his first real essay, "Un nuovo corso per il cinema italiano" (A New Direction for Italian Cinema; 1961), Rossellini attacks education for having sold out to specialization, forgetting the whole person. Culture has become a "pseudoculture" that does not represent the expression of an individual artist but is "manipulated by technicians to placate in different ways the anxiety of the masses," who are crushed by "the insistence on orthodoxy, obedience, and blind faith in the elite." These products of the pseudoculture are addressed simultaneously to children and adults, Rossellini complains, with the result that the former grow up too fast and the latter are kept in a state of childish conformity in which they want to be "maternally protected" by strong leaders.

Is there a way out of this mass conditioning? Rossellini suggests that, because half the world is illiterate and people learn best through audiovisual means, the mass media must become vehicles for the spread of "ideas and information which will allow man to begin to understand the complex world to which he belongs." Human beings are naturally curious and if offered mental stimulation will accept it gladly. Why do we not "feel a profound emotional impulse contemplating the conquests that man has achieved in the last two centuries?" he asks.

We need to spread among the masses the true essence of the great discoveries and of modern technology. . . . Doing this, we will help the large masses find themselves in the new world. . . . In order to rediscover man we must be humble, we must see him as he is and not as we would like him to be according to predetermined ideologies, and this, it seems to me, was one of the merits of the neorealist cinema.[3]

In another open letter, this time addressed to Senator Renzo Helfer, the undersecretary for the arts, Rossellini inveighs against the "false problems" of sexuality, loneliness, and juvenile delinquency.[4] But, as he maintains in the important Cahiers du cinéma interview in 1962, "education" is not the answer either: "I reject education. Education includes the idea of leading, directing, conditioning, whereas we must search for truth in an infinitely freer way. The important thing is to inform, to instruct, but it's not important to educate."[5] What lies behind this seemingly frivolous distinction between education and instruction is Rossellini's firm, and apparently untroubled, view that pure information, pure knowledge, can be conveyed neutrally. And where is information most pure? In science, of course, and thus his future project will be "to try to see with new eyes the world in which we live, to try to discover how it is organized scientifically. To see it. Not emotionally, not through intuition, but in its totality and with the greatest exactitude possible. What our civilization has given us is the possibility of conducting a scientific investigation, of examining things deeply in scientific terms, in other words, in such a way that errors, theoretically, can be avoided if the investigation is properly conducted. Today we have the means for working in this way, and it is here that we must begin to take up a new discourse" (p. 10).[6]

He compares his work to that of the encyclopédistes of the eighteenth century, but when asked if it "will have as its goal the destruction of the present capitalist world" (a question that surely must have been asked tongue in cheek), Rossellini responds that he does not know what the outcome of his work will be, but that he certainly does not want to "play at being a revolutionary" (p. 12). In any case, his work will be easier than that of the encyclopédistes , he says, for we now live in an age in which science is universally respected, and "a scientific world must logically produce scientific solutions" (p. 12).

What is especially interesting is that, at the time of this 1962 Cahiers du cinéma interview, Rossellini's creative fortunes were at their lowest point and, as we have seen, he had begun to distrust cinema itself. It has failed to become the art of our century, it has in fact been one of the chief causes of our present sad state, but even more fundamentally, its very nature seems to have kept it from dealing adequately with general ideas. He maintains that, as it stands now, the cinema only allows for small variations within a basically standardized product. Nevertheless, if the cinema is not useful for reopening the great debate, it still will have its function as documentation:

Film should be a means like any other, perhaps more valuable than any other, of writing history and of keeping the traces of societies which are about to disappear. Since, more than any other means of transcribing reality that we currently possess, today we have the image which shows us people as they are, with what they do and say. The protagonists of History are photographed

with their voices, and it is important to know, not only what they say, but also how they say it. Now, the means which film possesses have sometimes been used for propaganda, but have never been used scientifically (pp. 13–14).

It is significant that, in the context of the "scientific" (or historical) film, Rossellini once again seems able to believe in the power of cinema to "show us people as they are." Increasingly, in other words, his earlier misgivings about the realist aesthetic seem to become displaced onto fiction films alone.

By 1963 Rossellini's ambivalent feelings concerning the visual image are completely gone. Geography and science can be much better taught through audio-visual means, he now decides; "The image can remove abstraction, analysis, and dogmatism from material which is primarily literary in content." Now he believes that words should be left to experts and specialists. Outlining what becomes essentially his own program, he says that with film we can finally understand history not as a series of dates and battles, but socially, politically, and economically. Above all, "Certain characters, psychologically reexamined, can become, through their human qualities, models of action." Seeing is now so highly privileged for him that it becomes the equivalent of understanding: "It is not a matter of giving up the pedagogical virtues of the scholastic tradition, but of giving them a new style, which is the style of those who are able to see, and therefore to understand."[7] In remarks made on a 1972 panel examining the state of Italian television, which were published in a book called Informazione democrazia , Rossellini moves even further toward a concept of pure, direct vision, to which he will later devote an entire book:

Images, with their naked purity, directly demonstrative, can show us the road to take in order to orient ourselves with the greatest possible knowledge. . . . All of our intelligence, as we know, expresses itself thanks to the eyes. Language, this human conquest which has justly been divinized (it is said that God is the Word), is the ensemble of the phonetic images by means of which, not being able to fix and save the images, we have catalogued all of our observations, the great majority of which are visual. [Language] has allowed us to express our intelligence by discerning, classifying, and connecting. Today, finally, we have the images; we have television, we have the RAI.[8]

What is noteworthy here is Rossellini's choice of words: "naked purity," "directly demonstrative." This is nostalgia for a pure, whole presence—with a vengeance. In this scheme, pictures speak directly, naturally, without mediation, and language was invented as an afterthought, little more than a poor filing system even if divinized, merely to be able to catalog and fix permanently what our eyes have already taught us. Again, what Derrida has called the logic of the supplement is at work here, for this impure language that Rossellini describes, this language that represents a falling away from the plenitude of the visual image, is paradoxically the only way, structurally and historically, in which that pure vision vouchsafed to us could be preserved or even expressed. Now that the RAI (Radio-televisione italiana ) has restored the image to us, however, meaning will once again be direct, unproblematic, safe from the play of difference. What the director wants to forget is that, since this image is always a representation itself,

it must employ prior conventions of representation to be understood: in short, images speak a language too.

In a 1963 essay Rossellini expresses the familiar romantic desire to "reexamine everything from the beginning," without asking whether such a return to a moment of pure origin is ever possible. Neorealism is looked back upon fondly as an example of this "starting from zero," completely free from "false intellectualism." We must examine everything in its "origins" and, like a schoolteacher, "try to tell the story of the great events of nature and history in the simplest and most linear fashion." Rossellini fails to see that linearity itself is already an interpretation of history. He insists that "we have to begin the discourse from the very beginning, from the first letter of the alphabet." But can we have a "first" letter without already having all the others, too? Over and over, Rossellini expresses a need to go back to "data that is impossible to confute,"[9] presumably to find—or construct—a ground that will not give way.

What we need now, the director tells us, is a cinema that is "didactic, also in the Brechtian sense."[10] The entire structure of filmmaking must be remade in the light of this new function, and all fancy technique must be forsworn in the interest of making films as cheaply as possible. What is especially annoying to Rossellini is the refusal of modern art to deal with contemporary industrial and technological reality. In 1965 he outlined to Aprà and Ponzi "the overwhelming victory of man over nature":

But tell me who has been moved by it, what artists have dwelt on this amazing fact, which is at least equal to the discovery of fire, in fact greater. . . . Above all you have to take the reins of this civilization and be able to drive it towards ends that have to be thought out quite clearly and precisely. But instead, strangely enough, as science and technology advance—and I mean science and technology in the highest sense, the sense of knowledge which is human in its very fibre—art abandons itself to daydreams in the most irrational way imaginable. You build a rational world and the whole of art takes off into fantasy.[11]

Above all, as Rossellini tells Cahiers du cinéma in another interview in 1963, this new reality must be regarded from a "moral position," a phrase that recalls his earliest formulation of neorealism. And whence comes this moral position? From love and tenderness, which is lacking in most forms of modern art such as the nouveau roman and contemporary painting, which only make man even more infantile with their constant complaining:

Today, you know you are in the avant-garde if you are complaining. But complaining is not criticizing, which is already a moral position. From the moment you discover that someone can drown if he falls in the water, and then you throw people in the water every day to see this abominable and terrible thing, that is, that the people you throw in the water can drown, I find that absolutely ignoble. But if, when I've realized that the people who've fallen in the water are drowning, I begin to learn how to swim so that I can jump in the water and save them, that's something different. And that's what caused me to give up making films, as I told you last year.[12]

He no longer cares about "making art"; rather, he wishes to become "useful." He explicitly rejects the role of artist in favor of that of craftsman.

For Rossellini, the art of our century has shamefully neglected to confront its great (and obvious) subject. How much have we tried to understand science from a moral point of view, "in order to penetrate it, to participate in it, and to find in it all the sources of emotion necessary to create an art?" In an earlier era, artists were directly involved in the development of man's consciousness. Men like Leon Battista Alberti (the Renaissance figure who appears in several of the films to come) saw no conflict between art and science, and insisted upon the importance of mathematical perspective and anatomy to architecture and painting. These artists "were able to plunge into a scientific reality, appropriate it, rethink it and bring it up to the rank of a superior art." Nor does Rossellini mean that all art must become figurative and literal again, for understanding can be expressed abstractly as well, and the true artist "can, with a single, pure, bare, abstract line give you the emotion that comes from his knowledge."

And how will Rossellini himself contribute to the elaboration of his ideas?

The next film I make . . . but I don't want to call it a film, because it must not be of the cinema. Let's say "I'll put on film" the history of iron. Does that seem ridiculous to you? A guy who begins to do the history of iron, that's ridiculous. But I want to offer myself not as an artist, but as a pedagogue. And there will be so many extraordinary things, which will give you such a quantity of emotions, that, while I won't be an artist, I'm sure that I will lead someone to art.[13]

As we have already seen, Rossellini's pedagogical project raises many epistemological and historical questions that, more often than not, he refused to consider as seriously as he should have. His charm and unshakable certainty about what he was doing led most of his many interviewers, unfortunately, to be lenient with him, retreating in the face of what sometimes even becomes dogmatic assertion. But the questions remain, and they are not all of a theoretical order.

The first, rather minor, problem is to ascertain just who is the "author" of these films. L'età del ferro and La lotta dell'uomo per la sua sopravvivenza , after all, were directed—at least according to the credits—by Rossellini's son Renzo, who had been working with him as an assistant on the set since General della Rovere .[14] Rossellini was fond of shocking interviewers by telling them that the famous solitary banquet scene in Louis XIV was actually filmed by Renzo while the elder Rossellini was visiting his daughter Isabella in the hospital. (One strategy here, of course, was to demystify the idea of the creative artist in favor of the skilled craftsman.) Elsewhere, when questioned closely concerning the particulars of L'età del ferro , he replied, "Look, I did very little. My son Renzo did it all, he's the director. I only thought the idea up."[15] But then he goes on to explain in great detail what were, in effect, his artistic choices. The simple truth is that no matter what he might have said to the contrary, these are his films. He conceived, researched, wrote, and produced them. Renzo had, in fact, so totally absorbed his father's methods by this point that he was

in effect simply able to substitute for him without missing an artistic beat; nor did he make any measurable personal impact on these films himself. As Rossellini had been saying as early as the postwar period, most of the actual shooting bored him terrifically; now, with a grown-up son, he had found the perfect solution to the tedium of day-to-day filmmaking.[16]

The plan for the filming of L'età del ferro , for example, was for the father to write a screenplay of sorts in blocks of three or four days, which Renzo would then shoot while Rossellini père stayed at home working on the next section of script. As Renzo explained to me in 1979, however, the situation was not a happy one for him:

It was a perfect collaboration but it had its limits. I had to copy his manner of filming exactly. I had to conform my filming to his style, which was not mine. And because there was such a difference in age between us, naturally our visions were different. I would have wanted to develop the spontaneity of the takes, because for one thing I had a lot more enthusiasm for the medium. Instead I had to be very cold and distant. And the tiniest details could seem to him like giving in to the worst kind of formalism. To give you an example from L'età del ferro: At one point, the metalworker looks into the German truck to see what is inside. He pedals on a little further, then looks again and sees something. Well, the fact that I shot the sequence this way became such a big deal! My father said it was out of Buster Keaton, something from the thirties American film, a "double-take"! After all, he said, when somebody looks, he looks, and that's it. How terrible. This tiny little detail of the fiction, interpretive if you will, was for him absolutely unbearable. I enjoyed telling stories, therefore coloring them a bit, to add elements of fantasy to the story, to work with the actors, to be more what he always deprecatingly called a "cinematografaro." I wanted to use all the different means available to cinema, which seems natural in someone who loved the cinema so much. He thought all of this was "formalism." And so most of our arguments stemmed from this basic conflict, a conflict of form. I felt frustrated that I couldn't give it all that I wanted to. Instead, I had to copy perfectly his style [calligrafia ]. This kind of thing made me eventually decide not to work with him any more, though I did shoot about twenty percent of Louis XIV and a lot, more than sixty percent, of the Acts of the Apostles .

Even these, then, must be considered his father's films.

Another, more complicated question about this new work for television concerns the formal relation between it and Rossellini's previous work destined for theatrical release. Now that he had denounced commercial filmmaking, it seemed important to him to insist that there was absolutely no difference in the two media. It is a commonplace in film theory that the spectator's psychological relationship to the larger-than-life theater screen is quite different from his or her relationship to the tiny screen that is looked at and can be walked around. The quintessential medium of the close-up, television generally foregoes the extreme long shot because it is simply too difficult to decipher. In an interview that appeared in Filmcritica in August 1968, however, Rossellini insisted on focusing solely on the economic differences between television and film, preferring television because it allowed more experimentation. When questioned about the formal or technical differences between the two media, he fell back

on a fatuous analogy that the ideas of an essay will be the same whether it is published in a paperback or a deluxe edition: "The important thing is to say it. I've never had these aestheticizing worries; I'm completely devoid of prejudices from this point of view." Rossellini's other views on the subject are impressionistic and hardly provable, but are provocative nonetheless. Thus, further along in the interview, he claims that television is probably a better medium than theatrical film because spectators view the latter with "mass psychology," while, with television, "the (critical) spirit of the individual is more accentuated."[17] In the early seventies, Rossellini was again pushed on this point when an interviewer insisted that the "reading time" of each medium was different, and since the television screen was smaller, it was read more quickly. Rossellini responded:

I think it's slower. That is, the image that you get in the cinema is so powerful that it just jumps on you: therefore you more or less get it all in one impression. That of the television, which is much smaller and more reduced, must be analyzed in order to get an impression. So the process is different, and the time of reading television is longer than that for the cinema. But I don't pay any attention to it anyway.[18]

One last minor question concerning Rossellini's didactic project—and one that inevitably leads to subjective considerations—is that of audience interest. Rossellini clearly meant to address these films to a mass audience of nonintellectuals, and it must be asked whether they have ever been successful in that regard. Except for L'età del ferro , which, as we shall see, makes its own kind of concessions in the quest for a popular audience, most average audiences, one suspects, would find these films so lacking in action, either physical or emotional, as to be virtually unwatchable. Even intellectuals supposedly inured to this kind of thing have found Rossellini's television films trying, and while some avantgarde critics have called them the harbingers of a totally new and revolutionary cinema practice, others, like the redoubtable Richard Roud, who greatly admires the hardly action-filled work of Straub and Huillet, has said, "I find Rosselini's historical works something of a bore."[19] Obviously, this is a question that can only be answered individually.

Without a doubt the most important problem connected with the history films, however, as we have already seen, is Rossellini's apparently complete faith in his ability to present "pure information" about history, science, and technology. He never seems to have fully understood (or to have wanted to understand) that information is always and inevitably constructed from a given point of view. James Roy MacBean, in his discussion of Louis XIV , thinks that Rossellini's claim to be involved in "pure research" is "possibly disingenuous": "In denying any political intentions, he speaks of the need to 'demystify history' and to 'get at simple facts'; but it hardly seems possible that he is unaware of the essentially political nature of the act of demystifying history."[20] Goffredo Fofi has summarized the situation well in saying that "what is important to him is the research but not the method of the research, and his presumed lack of ideology is the most mystified and conditioned form of ideology which exists.[21] Again, Rossellini is acting as Barthes' bourgeois man who finds the world natural, but confused;

clear away the unnecessary confusion, and a direct perspective on the facts will be possible. He seems to have given up his earlier view that reality could be represented only subjectively, now insisting on the possibility of accurately representing the past. But since history is commonly taken as something fixed and "finished," unlike present reality, perhaps he had no other choice: admitting that our view of the past is always constructed, the product of a point of view, would simply have been too radical a step and would have undermined the entire project. Furthermore, as we shall see in later chapters, this epistemological certainty about history is crucial to Rossellini's project and has wide implications concerning the relation of capitalism, visual perspective, Renaissance humanism, and a great many other matters.

Perhaps Rossellini's most straightforward statement of his philosophy was made during a 1966 interview with Cahiers du cinéma .

CAHIERS: Do you believe in using ideologies as working hypotheses? For example, Marxism as a method of historical knowledge?

ROSSELLINI: No. You have to know things outside of all ideologies. Every ideology is a prism.

CAHIERS: Do you believe that one can see without one of these prisms?

ROSSELLINI: Yes, I believe so. If I didn't think so, I wouldn't have made my life so difficult.[22]

Another interviewer, some ten years later, was more persistent, and the exchange is worth quoting at length. When Rossellini told him that the plan of The Age of the Medici (1973) was to show the interrelation of humanism and mercantilism, Jacques Grant leapt forward:

That's what I mean when I say that your films take sides. Which also makes me believe that it's a stylistic matter. In the sense that you choose, from the lives of the characters which you put on the screen, very few events. For Louis XIV, you choose only those events which go in the direction of the taking of power by the bourgeoisie. The choices you make are obviously not innocent.

ROSSELLINI: What you just said is not taking sides. It's looking attentively at the givens. Taking sides means demonstrating a thesis.

GRANT: You say that because at this moment you only want to reason on the level of ideas. Taking sides means in reality choosing among the working of events. Let me ask my question in a different way: What is historical truth?

ROSSELLINI: It's the things which happened and which had led to certain effects.

GRANT: Therefore you choose your characters in terms of the important effects which they have had.

ROSSELLINI: Obviously.

GRANT: Which means that the careful realism you show in the historical films has a different meaning than the careful realism of your earlier films. Because in the earlier films, you showed a reality simply at the moment that it was happening, whereas in your historical films the reality shown serves to validate the effects. The choice of your objects becomes directly functional.

ROSSELLINI: You're wrong. They have the same role as in my other films. It is simply that they are less recognizable. It was the everyday of that given epoch.[23]

Despite the contradictions in Rossellini's position, however, it should be said in his defense that, as we have seen in the earlier "protohistorical" films like Francesco and Viva l'Italia! , the films themselves skirt the issue of historical accuracy by being adaptations of artifacts of the period (works of art, literary and historical documents) that exist in both the past and the present, rather than claiming to recreate the period itself. Furthermore, while it is true that these television films present the historical facts upon which they are based as natural and given, rather than the product of a certain perspective, they do not claim the same status for their representation of these facts. Anybody who has watched them will agree that one hardly identifies with the characters or becomes "caught up" in their plots. Nor could one claim that these cold, distanced films that reject personal drama and emotion nevertheless "place" the subject-spectator in exactly the same way that a classic Hollywood film does. To refuse to make distinctions here would make subject-positioning theories so general as to be useless. The evidence provided by the films themselves must also be taken in account. Thus, as we shall see, the heady and unstable mixture of L'età del ferro (part documentary, part lecture, part fiction film, part anthology), makes the film willy-nilly self-reflexive. The resulting lack of illusionism itself calls into question the natural stance implied in the "objective" compilation of facts, no matter what the director's overt intentions.[24]

The force of Rossellini's didactic project is vitiated by the obvious political and ideological problems surrounding it, but it is also important to understand the ways in which these films are successful. Above all, it is easy to forget, in an era like the present when most great Italian directors also work for television, how courageous Rossellini was to turn from the much more prestigious cinema to the mass media. (Pierre Leprohon, for example, sniffed at the time that "the medium to which he has turned is infinitely less subtle than the one he has deserted," without offering any specific examples.)[25] Rossellini's television films must also be examined in the context of the huge number of Italian "historical" films of the fifties and sixties. Typical of this period was the series of pictures based on the exploits of ancient figures like Ulysses and Hercules (who even unite, in one film, to fight the Philistines). Leprohon has said of these films, "Anachronisms and other errors become gags; and historical truth—if such a thing is even possible—becomes the least of the concerns of directors for whom character and plot are merely pretexts for unbridled fantasy."[26] In this light, the contradictions inherent in Rossellini's representation of history may seem less blameworthy.

At the very least, it is clear that these films often brilliantly depart from previous cinema practice, including Rossellini's own. One thing that sharply distinguishes them from conventional cinema, especially beginning with Louis XIV , is the reappearance of Rossellini's penchant for dedramatization, which now reaches its zenith. In these films, characters boldly foreground their words, paradoxically, by delivering them in a flattened, often completely uninflected way. Physical movement is also minimal, and the consequently static nature of most visual compositions tends to focus attention, like the words, on the ideas and historical forces at work. And Rossellini is resolutely uninterested in his figures' emotional or psychological lives; all potentially emotional encounters

are leveled, and there is little or no probing into an individual historical figure's character to discover the nature of his personal motivations.[27]

Claude Goretta's Les Chemins de l'exil , an excellent film on the life of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (which Rossellini had once contemplated making) is instructive in this regard. The advertising that accompanied this film upon its release in 1978 proclaimed that it was in "the great tradition of Rossellini's historical films," and to a certain extent, especially in comparison with most historical films, it is. For one thing, importance is laudably given to the development of Rousseau's ideas as well as to the contours of his life. The pace is slow and delightfully contemplative. But here the similarities end: the actor playing Rousseau situates himself clearly in the classic acting tradition, with abundant emotional expression, and Goretta has included many conventional character tics meant to "humanize" Rousseau. This is not wrong in itself, of course, but it is not Rossellini. Similarly, Goretta is quite obviously intent on the production of beautiful compositions and, much more than Rossellini, often allows themes to develop through the stylistic and iconographic content of the images themselves. Likewise, lighting is often extremely dramatic, and color is used extensively to heighten mood and emotion. Goretta's camera is itself so fluid and mobile that Rossellini surely would have considered it obtrusive. In spite of Goretta's increased commitment to Rousseau's ideas, in short, a great deal of emphasis is placed on Rousseau's personality as well, very much in the tradition of the Hollywood biography film. Yet while the audience is more involved emotionally in this film than it would be in a Rossellini film, it still manages to come away from it with a fairly comprehensive view of Rousseau as thinker and historically important figure.

Rossellini's increased emphasis on dedramatization and his refusal to create characters who would be convincing according to conventional codes of realism parallel his lack of interest in making viewers lose themselves in the diegetic space, making them feel that they are really there. Rather, a consistent yet unobtrusive, low-grade alienation effect pervades these films. Rossellini's mise-en-scène and his reconstructed sets attempt to be suggestive of a given historical period without actually trying to recreate it. In this way, the sets differ drastically, say, from Griffith's painstaking "historical facsimiles" in The Birth of a Nation . Nor is Rossellini's space crowded with the hustle and bustle of the DeMillean "cast of thousands." Instead, virtually all elements of the set are there for a specific reason: to convey an idea of the past era, or rather, to convey that particular era's ruling idea or ideas. The sets of Augustine of Hippo , for example, resemble line drawings rather than sumptuous historical paintings, since this bare-bones symbolic sketching, as opposed to realistic illusionism, fits perfectly with the general characteristics of early Christian art. In this way, as we shall see, many of these films attempt to recreate their eras in terms of the received visual images that have come down to us via the art of the period, enabling Rossellini once again to be complexly in the past and the present at the same time and also to suggest, self-reflexively, the source of our visual knowledge of the past.

Typically (except in Louis XIV , where sumptuous display is precisely the point), Rossellini contents himself with the minimal representation—usually

basic costumes and bare settings, chosen with a brilliant eye—which further foregrounds the idea that is being spoken. The reality Rossellini wants, despite his later insistence on the "directness" of the visual image, is, after all, in the words, both because they are "authentic," since they are taken from available historical sources whenever possible, and because what he wants to convey, finally, are ideas, which, whether he likes it or not, are in the words. Hence he is never tempted by a Belasco-like obsession for actual period detail. What he is looking for in all these films, once again, just as with his humans twenty years earlier, is always an essence .[28]

Having now considered in some depth the overall strengths and weaknesses of Rossellini's grand historical project, it is time that we move on to a discussion of the specific films themselves.

28—

L'Età del Ferro

(1964)

At the time of India , as we saw, Rossellini was not really very interested in the medium of television, and the episodes broadcast were little more than outtakes from the later theatrical version. By 1964, however, when Rossellini had begun to take television more seriously, he had learned many things. One of them was that the commentary should add something to the images rather than try to replicate them verbally, as it had in the television series on India. In L'età del ferro (The Iron Age), therefore, the director appears on-screen, acting overtly as teacher and serving as a guarantor of the images, as it were, rather than as their competitor.

His goal in this five-part series is nothing less than a comprehensive overview of the entire Iron Age from the time of the Etruscans to the present day. Most of the early segments are devoted to the progressive refinement of iron implements and weapons, as we move from the earliest inhabitants of the Italian peninsula through the Roman era, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, the eighteenth century, and the Industrial Revolution, finally coming to rest at an iron factory at Piombino during World War II. In the fourth episode, Rossellini boldly and imaginatively transforms his documentary into a fictionalized account of one metalworker's dealings with the Nazis and the Resistance. The final segment examines the present reality and the future promise of our technological society.

Bursting with what is for the most part recently acquired knowledge, the new teacher wants to teach us everything, all at one go. He will learn, as all teachers must, the virtues of pacing and selection. In fact, in the years to come, he will go back over much of this same material to expand and deepen his and our understanding of it. The series is also clearly transitional, for many of its

dramatic strategies are little changed from the string of commercial films that began with General della Rovere in 1959, and bear little relation to the rigorous films to come. Rossellini is clearly grasping for the large popular audience that had eluded him since the glorious days of Open City , for now he has a mission. In the pursuit of this audience, he is not above resorting to the fast cutting he used as far back as La nave bianca (1941). The battle scenes, for example, are exciting in the best conventional sense. The very first scene, in fact, opens with a thrilling boar hunt shot principally in a flurry of close-ups; the scene becomes increasingly frenetic and, when the dogs hang onto the wild boar for all they are worth, very convincing. Yet even here Rossellini seems, as in the films to come, less interested in dramatic verisimilitude, and the characters' dialogue is often openly, even painfully, expository. The fast cutting and high drama of the chase and battle scenes, in other words, are always thematically subordinate to explanation and demonstration, clearly the order of the day.

This atypical desire to entertain through spectacle also accounts for the astonishing inclusion of scenes from earlier films (including Paisan and Abel Gance's Austerlitz ). As he explained to his Spanish interviewers in the early seventies:

It's very important to make the film spectacular because above all you must entertain people. These are films which should be of use not just to intellectuals but to everybody—if they were not it would be pointless to make them. They have to be spectacular and that means spending a lot of money, which you can't do for TV. These are cultural programmes and so they come furtherest down in the television budget. If you try to fight to change this you don't get any films made, and the important thing is to make films. So we took some sections of other films and re-used them in a different context, and in this way we got the spectacular effect for much less.[1]

In many ways, this is a desperate Rossellini speaking here. He is anxious to be successful in the new medium, obviously his last chance. To continue working—and what is life without work?—he knows he will need to be financially successful, or rather, financially inoffensive, spending as little as possible, continuing to amaze backers by how cheaply he can work.

The most important aesthetic effect of this borrowing, beyond pragmatism and economic exigency, is to establish a kind of conscious, fruitful intertextuality. In order to fill the five hours of time, Rossellini borrows freely from Austerlitz for the Napoleonic scenes, from Paisan for the immediate postwar scenes, and from Scipione l'Africano, Luciano Serra, pilota (upon which he had worked), other fiction films, and a certain amount of raw documentary footage. For one thing, this strategy marks a new variety of an old proclivity of the director's—the conscious working against the Hollywood-style slick seamlessness and "professionalism" that David Thomson has so masterfully dissected in his book Overexposures . Individual images now become secondary to Rossellini's larger project of discovering truth: "If you make a film in a very finished way, it may have a certain intellectualistic value, but that's all. What I am trying to do is to search for truth, to get as near to truth as possible. And truth itself is often slipshod and out of focus."[2]

What results from this mélange of documentary footage, older fiction film, on-screen directorial comment, and newly filmed "documentary" and fictional sequences is an intensely self-aware film. If Rossellini is seeking truth, he knows it does not come naturally. A revealing exchange in the Aprà and Ponzi interview is worth quoting in this regard:

Q: What's the relation of this kind of montage to what you talked about in your interview with Bazin?

A: It's not montage in that sense. There are some things I need to have which it would take months and months of work to make—I can find the same thing on the market, so I take it and use it in my own way—by putting my own ideas into it, not in words but in pictures.

Q: Don't you think that even before montage the pictures have a meaning that montage can't completely destroy?

A: They don't. You have to give them it. The pictures in themselves are nothing more than shadows.[3]

What is so fascinating in this exchange is that it is Rossellini who comes across as the avant-garde film theorist, articulating what is essentially a poststructuralist theory of meaning, and one especially close to some of Eisenstein's formulations concerning the relation of individual shots to the montage that, in a sense, constructs their meaning after the fact. For Rossellini—here, at least—these bits and pieces of earlier films are floating signifiers, in other words, unattached to any fixed, "natural" signified, and hence able to be shaped through montage (which Marie-Claire Ropars-Wuilleumier has linked with Derridean écriture ) into whatever meaning the filmmaker desires.[4] This is a long way from both neorealist orthodoxy and Rossellini's later notion of the "essential image."

In effect, Rossellini rearranges his unattached signifiers into a new genre, the film essay. "You have to use everything that can make a point firmly and with precision. . . . So I jump from film taken from the archives to re-constructed scenes."[5] These "pieces made for something else" are used as sentences, even as words, in the construction of his new discourse. But the fact that these visual signifiers have not been (and could never be) completely emptied of their original signifieds is made clear in an unintentionally comic moment in the last episode. As the film is touting the productivity of Italian industry, we see many shots of busy factories filled with happy, productive workers. If the viewer looks closely at the empty cartons, however, it becomes clear that what Rossellini is using is stock footage of a General Electric plant in the United States.

The first conceptual high point of the series comes with the introduction of Leon Battista Alberti, the fifteenth-century Florentine architect, scientist, and humanist who, as one of Rossellini's most direct stand-ins, will appear again ten years later, greatly elaborated, in the second and third episodes of The Age of the Medici (1973). Alberti is the perfect manifestation of all that Rossellini has been preaching because, for Alberti, "painting is science." Machines, quickly being developed by advancing technology, fascinate Alberti as much as they do Rossellini, whose camera enthusiastically follows their intricate movements, just as entranced as it was twenty years earlier with the powerful engines of La nave bianca .

In the first two episodes we also witness the beginning of the industrial production of weapons and learn about the bronze casting of cannons (as a little boy urinates on the metal in order to temper it); throughout, the emphasis is on the cannon's simultaneous utility and beauty. The screen is filled with wonderful machines, most of them employed in the manufacture of weapons of destruction, but nowhere does Rossellini bewail the fact that all this progress and creativity is in the service of death. We see the humorous side of it all—men fitted for armor as though they were at the tailor's (a hammer is used instead of a needle and thread), and the fighting of two men so overladen with metal (reminiscent of the tyrant of Francesco ) that they both collapse at the end from overexertion. We also witness what the film calls the "heroic struggle" to invent new ways to make more gunpowder, better rifles, uniform cannonballs—but with never a word of misgiving from the director.

It is at the end of the second episode that the most politically troublesome aspects of the series appear. For Rossellini, the Industrial Revolution and its aftermath seem to have been an unalloyed blessing. He now wants to demystify our notion of progress (a completely positive term for him), which, he contends, seems so miraculous only when its causes are unknown. Thus, he appears near the end of this episode to explain the causes of the Industrial Revolution, the invention of the steam engine, and the incredible development of machinery and production. Paradoxically, however, the massive onslaught of overwhelming statistics serves only to remystify the fantastic, blinding inevitability of everything subsumed in the word progress . Nor in this entire paean is there a single word about the exploited workers who were largely responsible for this outburst of creativity, or about the horrible slum conditions created in England and elsewhere in its wake. At the very beginning of the third episode, Rossellini does introduce the notion of class (appearing completely neutral toward it) and presents a few quick moments of documentary footage of strikes; then, suddenly, we are back into more war footage, and that is all we hear of the workers' struggle.

The remainder of the third episode takes us dizzyingly through World War I, Versailles, the rise of fascism, dirigibles, cars driving up the Campidoglio in Rome, coal mining, the manufacture of nylon, Hitler, the Japanese, and the Ethiopian war, following which Ethiopian sand is used to make machines that, in turn, are used to make spaghetti! At the end Rossellini summarizes the specific events leading to World War II, and the combination of shots, images, and facts presents a remarkably clear overview of the war itself. The accent throughout is purposely on guns and cannons in order to underline the historical and thematic connection with earlier episodes.

The fourth episode concerns itself largely with the fictional story of a metal-worker named Montagnani, who, like many Italians, was caught in the middle by General Badoglio's surrender to the Allies on September 8, 1943, while the northern half of the country was still occupied by the Nazis. When the Germans attempt to dismantle the factory at Piombino, Montagnani altruistically sets off on a bicycle to find out where they are taking the raw material. His travels lead him to Florence, as he follows first the truck and then the train that the Germans plan to use to transport the material to Germany. Coming at this point in the series, his story serves the function of an anecdote in an essay, told

for illustrative purposes. Montagnani is meant to be seen as a representative figure, yet he is also sharply etched in historical terms. As we journey with him, we also get a sense of the everyday lives of people simply trying to get along in the face of a great historical upheaval: we meet Fascists, common villagers, escaped British prisoners, and partisan train workers.[6]

Rossellini has included this fictional piece to make thematic connections with earlier episodes, for Montagnani is seen primarily as a man intensely devoted to his work and, therefore, to what will become of his factory. He takes pride in his labor, the pride of an artisan (linking him overtly to the craftsmen we have seen through the three thousand years depicted in the other episodes)—and is in no sense an alienated worker, resentful of management or private property. In this series, at least, Rossellini seems almost incapable of imagining this latter possibility. Instead, he offers an image of a harmonious relationship between management and labor based on a presumed commonality of interest, craftsmanship, and progress, a harmony barely conceivable in the context of real labor history. In this sense, the spirit of the film recalls the wished-for unity of Catholic and Communist at the end of Open City .

On one level the series attempts to create a picture of humanity deeply influenced by its history, environment, and, above all, the technology it has created along the way. (It is especially interesting that all of this is conceived in terms of a metal: Rossellini is right to complain that technology has been overlooked.) But his essentialist bias is still as strong as ever. For one thing, Montagnani is overtly offered as an Everyman figure who links our present-day world to the world of the past. Despite the superficial differences of modern civilization, Montagnani's view of his work, especially, is very little changed from the Etruscan craftsmen portrayed, in the first episode, at the dawn of the Iron Age. The many spatial and historical connections the film makes are also important for Rossellini's essentialist theme. Much is made, for example, of the fact that the government established the ILVA company in 1898 in order to exploit the mineral resources of the island of Elba, discontinued since Etruscan times, and that Piombino, the location of Montagnani's factory, is the ancient Etruscan city of Populonia, the site of the earliest iron works. Once again, Rossellini's insistence on carefully placing humans in history, in a given era and location, leads to a transcendent humanist view that is ultimately ahistorical.[7]

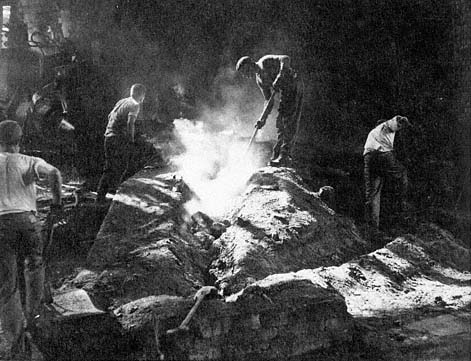

The history he recounts here, as in most of the didactic films, also has a strong teleological cast to it. In the final episode the war has ended, the Germans have been defeated, and people everywhere are looking to rebuild their lives; this larger theme is represented synecdochically in the quest of the factory at Piombino to begin production again. The factory manager piously intones, "Our duty is to give work," and the representative of the common man, Montagnani, is here reintroduced. He marvels at all the tremendous activity of rebuilding that he sees around him, his wonder replicating that of the engineer of the second episode of India who wanders about the site of the Hirakud dam he has just helped to build. When the workers pour molten iron into its form, we are visually reminded of the earlier episodes, and the message is clear that what we are watching are merely different historical moments of a single human enterprise whose final contours are preordained. At this point the film begins

The modern factory in L'età del ferro (1964).

praising the Italian economic miracolo to the accompaniment of stirring music, and Rossellini plunges into an orgiastic celebration of industrial productivity. Montage, presumably reflecting the masculine aggressivity of heavy industry, now takes over completely.[8]

Consumption is linked with progress, and, perhaps unsurprisingly for 1964, both are touted without a single word of doubt. The voice-over (which appears for the first time) warms to its task and begins shouting "Machines! Machines!" as it launches into a poetic outburst on the complexity of the equipment used to manufacture the refrigerators we see pouring off the assembly line.[9] Nothing could be more indicative of the shift from what Rossellini had begun calling the "morbid and complaining" films of the Bergman era to the new era of science and human possibility than the change in the portrayal of industrial machinery. In a climactic scene in Europa '51 , it will be remembered, machinery was regarded as threatening and dehumanizing; now Rossellini seems to have become so enamored of the machines' impersonal beauty that he has completely forgotten the reality of the human beings operating them. As Pio Baldelli has pointed out: "As usual, the director exalts the geometry of the factory buildings, the rational cleanliness of the tools and the products, the mechanical perfection of the gears, but he does not bother himself about the fact that behind the naked and rational walls men are working."[10]

Rossellini's reply to this objection, of course, would be that if men once began to understand the modern world they would no longer be alienated from it, and thus an innate hostility between man and machine cannot be assumed. What the director would have a more difficult time answering is Baldelli's complaint that the series shows

nothing concerning the cultural currents that feed a sort of business ideology which would like to model the perfect citizen of tomorrow and especially the patient worker of today, transforming him into an anonymous completer of tasks. "Democracy and well-being are the same," the instructor teaches. "The two decades of the Fascists were terrible, but look at the two decades of the Christian Democrats instead."[11]

As the final episode continues, the pace quickens. The voice-over, now almost feverish, shouts: "Motors! Life—always faster! Ve-lo-ci-ty!!!!" Even the words and phrases are broken up into sharp syllables that match the fast cuts on the image track. (One sight of this sequence alone would be enough to bury forever the simplistic notion of Rossellini as the man of the long take.) In fact, the fragmentation of voice and image, increasing continually in speed, is enormously exciting. The bizarre music also seems to fit perfectly as the voice-over applauds the uniformity that has permitted the economic miracle: "Few models! Thousands of cars!" Unfortunately, what seems to be elided here is that this uniformity has also spelled the end of the craftsmanship that linked Montagnani with the Etruscans. More importantly, Rossellini forgets that this very boom, founded upon uniformity, stepped-up production and consumption, and an uncritical faith in material progress, is exactly what his earlier films condemned as the cause of the selfish emptiness of figures like Irene of Europa '51 .

The pace continues faster and faster, now bringing in "Skyscrapers, bridges, freeways, ve-lo-ci-ty! Ships!" (Shots of engine rooms make the parallel with La nave bianca nearly exact.) "Jet planes! Two hundred seventy meters in one second!" (The second is counted aloud.) "Atomic energy!" And, then, "Space!" This is the final link that is meant to tie all the episodes together: the steel of the spacecraft takes us back into space, whence, as the first episode explained, the earliest peoples thought all metal had come. The series closes with a view of the harmony and world brotherhood that will result from all this amazing economic progress, making conflict obsolete and unnecessary: "We work! Everybody together! Everybody equal! Ex-enemies!" The pictures, music, and voice-over have combined to move the viewer profoundly with the possibilities before us. What excitement![12] Then the viewer recalls the succeeding twenty years since the series was made, and the naïveté and willful forgetfulness of its vision become apparent.

In spite of its flaws, however, it is clear that Rossellini's amalgam of fact and fiction, documentary and previous film is boldly new. At this point his historical project must have looked very promising indeed. He was fully installed in his new medium, after all, and ideas for projects were constantly occurring to him. Even at this early date, however, it soon became obvious that the commitment of the RAI was halfhearted at best, and the series was aired on five successive Fridays between February 19 and March 19, 1965, at 9:15 in the evening. As

Sergio Trasatti has pointed out, despite appearances, this was a quite unfavorable time slot, since it was up against "Weekly Appointment With the Theater," and whoever chose to watch L'età del ferro would have had to skip Julius Caesar, Antony and Cleopatra , and Sabrina . Naturally, L'età del ferro did poorly, gathering fewer than a third as many viewers as the other channel. Nor, unfortunately, was this treatment unique, for with it began a sad pattern that would help to make the historical films, Rossellini's last chance, a failure as well. As Trasatti reports: "L'età del ferro is one of the few important programs of the RAI which was never reshown, like almost all the work Rossellini did for television. The only exception is La Prise de pouvoir par Louis XIV , which was transmitted for the second time, in a celebrative key, the day following the director's death."[13]

29—

La Lotta dell'Uomo per la Sua Sopravvivenza

(1964–70)

Given the fact that the series was not aired until 1970 and 1971, most Rossellini filmographies quite properly list La lotta dell'uomo per la sua sopravvivenza (Man's Struggle for Survival) after La Prise de pouvoir par Louis XIV (1966) and even after Atti degli apostoli (Acts of the Apostles, 1969). Yet, La lotta is actually much closer in plan, scope, and technique to L'età del ferro of 1964, and was, in fact, conceived at the same time. Many critics have been bothered by the apparent inconsistencies involved here. Why would Rossellini return to the marathon view of history after the success of the much smaller-scale Louis XIV? It is useful, therefore, to know that Louis XIV was initially thought of as a kind of interim project while the work on La lotta was at a standstill. (This, too, can be misleading, however, for evidence from later interviews shows that Rossellini probably would have preferred to alternate between large-scale and small-scale projects.) In 1979 Rossellini's son Renzo, who is listed as "director" of the series, explained the chronology to me in the following way:

Acts of the Apostles and La lotta are very closely linked, because practically speaking, we made Acts to be able to finish making La lotta . We were filming the [earlier series] in Egypt when the 1967 Arab-Israeli war broke out. We were able to get out in time, but we had to leave all of our equipment behind. We had no idea how we were going to be able to finish the series, which we had originally begun in 1964. Louis XIV was just a slight interruption. We had spent a total of three years filming La lotta , and were a million and a half dollars in debt for quite a few years because of it, so when we went to Tunisia to shoot Acts of the Apostles , we shot the end of La lotta , which was the part that we had had to leave in Egypt, at the same time.

An early irrigation system in La lotta dell'uomo (1964–70).

La lotta , in any case, is surely unique in the history of the cinema; never before had a major film director conceived and executed a project on such a grand scale. The entire series runs a staggering twelve hours (Guarner reports that each of the twelve episodes was originally ninety minutes long and was later edited!) and even outdoes the ambitious L'età del ferro by surveying the entire history of humanity, beginning with the appearance of the first true men and women. Along the way, nearly every important historical era is represented in this exciting, if inconsistent, series. According to Rossellini, human beings stepped from their prehuman state when they first began to probe the mysteries of life and death, ultimately coming to revere the burial sites of their forebears. From there developed the use of the mind for survival and, for Rossellini, a concomitant belief in the supernatural. The earliest episodes of La lotta thus center around the agricultural revolution and the matriarchy Rossellini believes was a natural consequence of the relation of women to fertility and the cycles of the moon. From there we move to astronomy and the discovery of the solar year, the Bronze Age, the first machines, the rise of Egyptian, Greek, and Roman civilization, the barbarian invasions, the advent of Islam, the Middle Ages (including the preservation of ancient learning and the founding of the great universities), the Renaissance, the beginning of science and technology, the invention of electricity, the telegraph, radio, right up to the present era of space travel itself. Along the way,

a surprising number of dramatizations show us such figures as Hippocrates, Christopher Columbus, Benjamin Franklin, and Gutenberg, all engaged in the struggle to advance human welfare. It is a breathtaking enterprise, perhaps one that could have been undertaken only by a man with the self-confidence and audacity of Roberto Rossellini.

A project of this sort would have to be gargantuan in terms of its support as well. Sergio Trasatti reports that the entire series cost over 800 million lire (well over a million dollars), with the RAI contributing 120 million lire and the French, Romanian, and Egyptian television networks financially involved as well. Certain of the medieval sequences, for example, were enormously costly, especially for a television production: the Crusades alone, according to Trasatti, required some eleven thousand extras. Since one of the prime reasons that Rossellini moved to television in the first place was financial, the expenditure of such huge sums presents something of an anomaly. In fact, Rossellini's production company was so strapped by the series' cost that he had to forgo accompanying his new television film Socrates to its premier at the 1970 Venice film festival. Instead, he went off to Latin America where he managed to interest several countries in showing the series on their networks.[1]

Rossellini later said that he wanted La lotta to provide "a sort of spinal cord to which I would attach the other productions."[2] Elsewhere, he described it as

a history of new ideas, of the difficulty of getting them accepted and the painfulness of accepting them. The whole of human history is a debate between the small handful of revolutionaries who make the future, and the conservatives, who are all those who feel nostalgia for the past and refuse to move forward. The film gives an outline of history—I think it's useful as a start, because school study programmes have degenerated so and don't meet modern needs. It gives me a kind of core around which I shall take certain key moments in history and study them in greater depth.[3]

As such, the new series was conceived as a complement to L'età del ferro and another fully planned series on the Industrial Revolution, which was never filmed.[4] Later in the same interview Rossellini outlined the specific relation of La lotta to L'età del ferro:

It's a matter of looking at history from different angles. La lotta is much more concerned with ideas, which are always related to technology as well. The agricultural revolution was a great advance for mankind, the first great revolution carried out by man, because from then on man was not so completely at the mercy of nature and began to use it to strengthen himself. He no longer feared nature and gradually embarked on the decisive conquest of it. L'età del ferro is more concerned with the development of technology. The technology of iron brought advancement, and changed men's way of looking at things.[5]

In terms of technique, La lotta is clearly a more confident step beyond the uncertain mixture of L'età del ferro . The earlier series' bricolage of dramatized scenes (both factual and fictional), documentary stock footage, and sequences from older films was a fascinating experiment whose enthusiasm compensated for its failures. With La lotta , however, the rough, if exciting, hodgepodge dis-

appears, and virtually all of the material, with the exception of the NASA stock footage of space travel, is presented in a dramatized narrative form, of either famous events or representative fictional details meant to convey the spirit of an age. The result is a slicker product, certainly, but I am not sure that Guarner is right to herald the abandonment of "archive material" as a definite advance in technique.[6]

Similarly, there seems to be much more attention being paid here to such formalist concerns, normally disdained by Rossellini, as composition and an aestheticized mise-en-scène. The color is also handled magnificently in the film—clearly a lesson learned from Louis XIV , with subtle pastels of green and brown and yellow, say, predominating in the episodes on early Egyptian civilization. Mario Nascimbene's music works well, moving, finally, beyond the limitations of Rossellini's brother's conventional Hollywood scoring. The Pancinor zoom orchestrates the choreography of every scene, and Rossellini is not afraid to shoot an entire lengthy sequence in one or two long takes. Onlookers explain to each other (and to us, of course) what is happening in each scene, as, for example, when the engineer describes the plan of the pyramids to the pharaoh. Individual frames sometimes even suggest the predominant art form of the period, though this device, which becomes increasingly important in the films focused on individual figures, is here naturally much more diffuse. The matte and mirror shots are also more convincing in La lotta , especially compared with the later films that were hampered by tiny budgets. (This would seem to indicate once again that any talk of Rossellini deliberately making the matte shots obvious simply misunderstands the director's own sense of professionalism.) Also, as we saw in L'età del ferro , Rossellini continually makes cross-references throughout the course of the series to remind us of the central motifs: thus, the burial and religious customs of many different civilizations are depicted, as well as the passing of power from one generation to the next, the use of water and machines, changing views of medicine, the advance of technology, and how ordinary things of the world like bread, glass, and paper come to be made.

Given the sheer size of the series, and the fact that the chances of it ever being seen in the United States (or elsewhere, for that matter) are quite small, I will have to limit myself to discussing in detail only one of the episodes. Since a polemic has developed most violently around the notion of matriarchy articulated in the opening episode, it will perhaps be best to concentrate our attention there.

The opening credits attempt to put what we are about to see, the earliest struggles of primitive humans, in the context of the present and the future so that we might marvel at how far we have come. Following obviously from the euphoria of the last episode of L'età del ferro , the credits are jazzy and hyped, and as we hear black Americans singing, we watch shots of New York skyscrapers and rockets blasting off into space. (For Rossellini, America is the principal locus of the energy of the new technology, and it is no accident that in the early seventies he was to work happily for a time at Rice University's Media Center with Houston's many scientists.) After the credits, the director himself comes on to emphasize how short a time humans have been in the ascendancy on the planet, an idea that has become by now something of a cliché, and that intelligence has

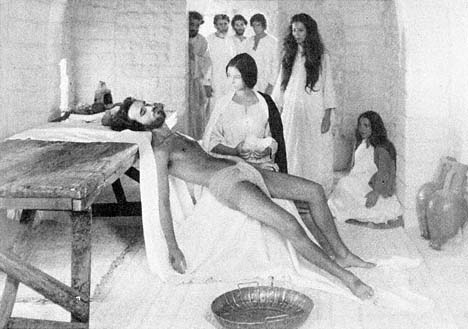

always been their greatest weapon. The first sequence, the Ice Age, opens with shots of snowy woods. A cold wind blows on the sound track and the voice-over (not Rossellini) explains, over the sound of a single violin note, what we are seeing, but without ever overexplaining. (Often the voice-over is completely silent, wisely letting the visual track speak for itself.) Cave dwellers appear, and we learn that humans have already survived four ice ages and that the sheer brutality of nature has made them move into the mutual protection provided by communal living. The discovery of fire and cooking follows quickly, along with hunting and animal keeping. The breasts of the actresses playing the cave women are exposed (something difficult to imagine on American television in the sixties), and this fact, along with the superb costumes and the lack of makeup for the women (another benefit of using nonprofessionals) makes these scenes seem less awkward than the standard depictions of prehistory. Human beings begin to gain the upper hand over their animal foes when, through the use of their intelligence, they disguise themselves as animals. A short night scene then shows us the benefits of an increased security: one of the men, because he has become more reflective about the mystery of the world, begins to draw on the walls of the cave, and art is born.

The next scenes of the first episode show the end of the Ice Age, men and women beginning to eat roots and berries, washing clothes, abandoning caves for shacks, and learning to make bread by milling grain with a stone. An entire set is constructed merely to show this last activity, a sequence that occupies no more than a few moments of footage; obviously, Rossellini's preference for television because of its economies did not prevent him, on occasion, from thinking big. No dialogue inflates the scene depicting the establishment of agriculture, and the sound track is occupied only with strange, but understated, electronic music that contrasts favorably with the exuberant, blaring score of L'età del ferro .

As in all of the history films to come, much time is spent on the supposedly insignificant details of everyday life: food preparation, work, and daily chores. Rossellini's intellectual proximity to the French annalistes school, which was beginning to flourish at this time, thus also becomes clear. Similar to his use of temps mort in the earlier fiction films, the accent in the history films will be on downplaying the "grand events" in order to concentrate on ordinary life. This is the essence of Rossellini's historical method: the selection of revealing, though seemingly minor, details that are meant to represent, synecdochically, the consciousness of an age. The director himself provides an example in several interviews: a vizir who runs a gold mine far from any water source finds that his workers and animals are dying so fast that the mine is not productive. He goes to the pharaoh, who was considered the equivalent to a god, and asks for a miracle. The pharaoh logically declares that the vizir should take ten thousand men and dig a canal from the Nile to the mine; to us simply logical, but the vizir is astonished and calls the idea a "miracle." Rossellini's comment is that "through a thing like that you can discover the proportions of a civilization much more than any other sort of thing."[7]

The principal purpose of deemphasizing the grand events is, once again, to establish an essence of human nature. Rossellini would later explain:

In general, books of history tell us about the main events. History was also written to glorify power. But the real history is to discover man, the simple man whose life was never written. The research made in the last years is great in this sense, now you can find out a lot. History is the history of human beings who are like us, only chronologically at another moment in time. We have some knowledge and what we do now [sic]? That is the continued struggle of man.[8]

Thus, the director dedramatizes history partly for Brechtian purposes, so that the spectator may watch intelligently and understand the issues rather than being involved emotionally with the character. But more importantly, this is how one arrives at the human essence. True, we must be scrupulous about historical specificity, but we will inevitably find that "history is the history of human beings who are like us."

The focus of the first episode now turns toward the establishment of the matriarchy: since man's role in reproduction is unknown at this point, the fertility of the woman, the source of all life to an agricultural people, becomes exalted. A lovely sequence, enhanced by a perfectly executed zoom shot, shows the queen giving herself over to the power of the water so that she may become fecund. The role of the male changes when his part in reproduction becomes better understood, but the prestige still belongs to the woman: the consort must wear artificial breasts when he gives orders, and later he is ritually slaughtered so that his blood may fertilize the soil. Once astronomy begins in earnest, however, and solar time is privileged over lunar time (the latter associated with women), the male's ascendancy begins. As Rossellini later described it: "At the moment when the Hellenes, who had their own gods and were not agricultural people but shepherds, came from the East to the Mediterranean area, it became a patriarchal society. All Greek mythology is an explanation of what happened during that change from a matriarchal to a patriarchal society."[9] The first episode of the series ends at this point.

The utterly sweeping nature of Rossellini's generalization about the establishment of the patriarchy is indicative of his overall approach to history in this omnibus series. With the conviction of the autodidact, he is able to state categorically the single cause of an enormously complicated system of beliefs and cultural practices. On the other hand, it is true that the cautious steps of the scholar would be out of place when it comes to making a television series on the history of the world. In any case, for Rossellini the message was clear: given all that we humans have accomplished in the infinitesimal time we have occupied the planet since it first came into being, we must not give in to the naysayers and complainers who preach alienation. Instead, we should feel hopeful that we can and will solve the problems that confront us today. What Rossellini has perhaps forgotten in his enormous optimism in human potential, however, is that the movement of technology has developed a life and trajectory of its own, which human beings no longer seem to control. It could also be objected that the vast majority of new technological developments, as Paul Goodman pointed out years ago, have come about to rectify the problems caused by previous applications of technology.

More serious is the problem of authenticity. Even the most intense Italian

supporter of Rossellini's television films, Sergio Trasatti, cannot help finding the undertaking so vast that a greater selectivity than usual is at work, with the result that the "objective and neutral" Rossellini is actually interposing himself more than ever. In Trasatti's words, it is "not an accident that La lotta seems to be the most opinionated of all these films." Nor can Rossellini's historical representations be legitimatized by the claim that he is relying solely on the testimony of authentic sources. As Trasatti points out, "In this film, more than any other, one notes here and there an obvious embarrassment concerning the lack of sources, the difficulty of verification, the complexity of the cultural relations among different facts and problems."[10]

In a sense, then, it is in this series that the inherent contradictions of Rossellini's method are most visible. It is not, of course, that the questions concerning the possibility of objectivity and authenticity do not arise elsewhere as well, but in better-documented periods it is easier for the director to deny his own mediation by appealing to the historical record. Here, on the other hand, when one is depicting the very beginning of civilization and societal life, one may have recourse to "the latest scientific knowledge," but the tactic is transparent. (He will have exactly the opposite problem portraying the too-well-known recent history of Italy in Anno uno .) Rossellini is offering an interpretation of events, in other words, and an interpretation based on very sparse information indeed.