3—

Un Pilota Ritorna

(1942)

Un pilota ritorna (A Pilot Returns) represents Rossellini's look at the second branch of the Italian armed forces, the air force; the army will provide the background for his next film, L'uomo dalla croce . Never mind inclined to discuss this film with interviewers, the director often grew quite testy with those who pursued the subject. Perhaps this is because the film was thought lost for nearly forty years, and since none of his interviewers had seen it, he may have thought that the less information he provided about another compromising film, the better. Un pilota retorna resurfaced, finally, in 1978.

One major reason Rossellini would not be proud of the film is that the subject came from Vittorio Mussolini (again under the anagrammatic pseudonym Tito Silvio Mursino), who acted as the film's supervisor, and who claims that he got Rossellini the job of directing. According to Mussolini, the film was quite baldly meant to "make known the heroism of our air force."[1] Massimo Girotti, who played the lead, later said that he considered it a patriotic film, though not propagandistic, even if the son of Mussolini was involved: "It was a dramatic film like any other, though with a heroic-patriotic background, of course."[2] The film's opening titles, however, are more direct. The first one states that "this film is dedicated with a fraternal heart to the pilots who did not return from the skies of Greece"; the second informs us that the film was made under the auspices of the "General Command of Fascist Italian Youth [Gioventù italiana del Littorio]." Like La nave bianca , in other words, it is not exactly propaganda, but it clearly propounds the official values of the regime. In one of his rare comments on the film, Rossellini told Francesco Savio in 1974 that he did not want to talk about it:

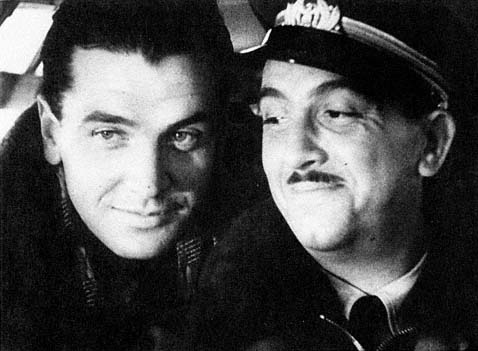

Men at war: Lieutenant Rossati (Massimo Girotti, left) and

fellow pilot in Un pilota ritorna (1942).

Courtesy of Intercinematografica.

Today it's becoming extremely disagreeable to talk about these things because it has become so much a way to proclaim yourself a victim of political pressure, which is also boring. I can say that certainly all the dialogue of Un pilota ritorna was changed. All of it.

Q: With regard to the original subject?

A: Yes.

Q: Which was by Vittorio Mussolini.

A: Well, it was just an idea. I always maintained complete freedom, and never started with little scraps of writing.[3]

At the beginning of this exchange, Rossellini hints at some form of political struggle over the film that he is too large-minded to excuse himself with. By the end, however, he seems merely to be referring to his lifelong practice of refusing to write out completed scripts before beginning production.[4] Though it is difficult to give credence to Rossellini's claim that all the dialogue has been changed, responsibility for the film remains uncertain.

The plot of Un pilota ritorna is slight and undistinguished, allowing the director to concentrate his attention elsewhere. (Interestingly, the young Antonioni also worked on the screenplay.) The action takes place in Italy and Greece in the early spring of 1941. The first part shows the Italian air force to great advantage, as it relentlessly attacks the Greek enemy. A young pilot

arrives in camp and becomes part of a squadron of older, more experienced men, and we are shown scenes of camaraderie that do little to advance the narrative. During an air battle, the young pilot's plane is hit, and he and his comrades must parachute to save themselves. They are captured, and the rest of the film shows them as prisoners of war, first of the British and later of the Greeks. In one of the camps, an Italian officer, gravely wounded in the leg, is operated on by an Italian doctor who just happens to be there along with his seventeen-year-old daughter. The young pilot, as might be expected, falls in love with the daughter. During an aerial bombardment, he manages to steal a plane and fly back to his home camp in Italy; from the air he sees the various landscapes of his country in a highly lyrical passage and, though under fire from his compatriots, manages to land safely, just in time to hear the news of Greece's surrender.

One major difference between this film and La nave bianca is that, while the documentary element is still very much in evidence, the fictional human interest aspect is stronger as well and more closely integrated into the whole. The attempt at a psychological portrait, however tentative, is obviously the most important change here, and one suspects that the inclusion of a talented star (Massimo Girotti, who played the lead in Visconti's Ossessione the same year) had something to do with this. Yet in spite of the increased psychological realism, Rossellini shows his willingness to oppose conventional filmmaking practice by refusing, at least in the first part of the film, to focus unduly on Girotti. Coralità is more important to the director at this stage of his career and thus we see the pilot as part of a group; only when the love interest becomes dominant is he emphasized as an individual.

Thematically noteworthy are the scene in which the pilots scoff at accounts of "heroism" in the newspapers and the overwhelming images of forlorn refugees that dominate the last half of the film. Little glory is associated with combat, and Rossellini's later, more fully developed theme of war as destructive of all human relationships is more than hinted at here. The pilot at times seems pleased about the Italian advance and at other times displeased. The final shot of the film is a close-up of his face after he has safely landed; all around him his fellow aviators are celebrating his return, but his expression is more enigmatic, a combination of relief and unease about the girl he left behind. In spite of its glorification of military life, in other words, the film also raises doubts about Fascist rhetoric. Furthermore, the pilot's captors are generally seen to be civilized and decent, ready to break the rules of the camp for a humanitarian reason. (With the sole exception of the Germans in Open City and Paisan , Rossellini will continue throughout his career to insist upon the humanity of the enemy.) Yet, later in the film, the British leaders seem completely undismayed about the prospect of making "a desert in front of the enemy." This, by the way, is said in English (and the Greeks speak Greek, sometimes at length), thus initiating an ongoing, rigorous allegiance to authenticity of language that will baffle many an Italian audience and even be complexly thematized in Paisan .

Un pilota ritorna is perhaps most interesting in terms of technique, which tends to mitigate its conventional melodramatic elements (such as the leg am-

putation scene with cognac as the only anesthetic). The controlled studio lighting makes it seem much more polished than Rossellini's later films, but the director seems to be striving for visual unconventionality as well. The editing, for example, looks forward to later experiments, for much of it is elliptical to the point of incomprehensibility. Similarly, a remarkable shot early in the film shows the pilots emerging from a theater; for an exceptionally long time all we see is a small bit of light through the curtain leading to the auditorium. A lengthy bit of dialogue goes on in almost complete darkness, and then finally several characters light cigarettes, illuminating themselves in the process. Even more daring is the 360-degree pan around the interior of the farm building in which the pilot, the girl, and the wounded prisoners have taken refuge. The pan begins with the girl reading aloud to solace the prisoner whose leg has been amputated, but by the time the pan comes back to her, we understand it as a kind of dissolve, and she is asleep. A world-weary sense of the destructiveness of war is the result.

Equally innovative, and characteristically Rossellinian, is the relative lack of interest in a strong narrative thrust. Thus, when the pilots take off on a bombing raid, a remarkably long time is devoted to the minutiae of their occupation and environment (altimeters, oxygen masks, and so on) before the battle begins. Later, they ride bicycles around the camp for no apparent narrative purpose; clearly, Rossellini is intent on giving us a picture of the pilots' everyday lives that refuses to be subsumed into the merely dramatic. Furthermore, emotion is drastically understated, as when a crew member indicates to the protagonist, by the slightest nod of his head, that the pilot of the airplane has been killed. The real drama, we come to understand early on, concerns the overall war effort, the large movements of armies, rather than the plight of specific individuals.

By far the most important, and most symptomatic, contemporary review of the film was written by Giuseppe De Santis for Cinema when the film first appeared in April 1942. Despite De Santis' obvious desire for something new, something "real," his model is still the illusionistic, dramatic, and psychologizing Hollywood style of filmmaking that, above all, follows a conventional narrative pattern. At the close of his review, he complains:

Each sequence of Pilota overlaps the next, neither one of them properly expressed because neither is concluded. What is the meaning of the pilots' visit, at the beginning of the film, to the girls of the city, if in the story the courage isn't there to get into its motives? What is the poetic necessity of that descriptive pan of the prisoners' shelter, when the girl reads something aloud after the operation? . . . What environmental coloring did Rossellini want to add when he has the aviators ride around the camp on bicycles during a break? If he meant to show us a documentary episode on military life, the episode itself should have told us something we didn't already know, in a narrative and psychological progression.[5]

Evident here is the demand for authenticity, the longing for the real thing—but a reality artfully arranged in a coherent, conventional narrative form—that was beginning to stir in Italian cinematic culture. Naturally, it was never

asked whether this narrative form itself was "true" and "real." For De Santis, each scene must have a meaning or point, an express purpose that furthers the plot line or the psychological portrait of the characters. No latitude is allowed for the aleatory or the "irrelevant," elements whose significance might transcend that of conventional narrative. To ask what is the "poetic necessity" behind this shot or that shot is to assume that every shot must contribute to an overall organic project, where every element works not for itself, but is subsumed into the whole.

But Rossellini was already thinking of alternatives to this model. Less than a year later, in fact, after having been forced to abandon his next project, Rossellini was discouraged about his prospects as a filmmaker and went to see the novelist R. M. DeAngelis. Out of work, he confessed to DeAngelis that, even though he did not know much about narrative technique, he wanted to become a novelist because he despaired of ever finding the wherewithal to make another film. But Rossellini was not satisfied with DeAngelis' definition of the novel and its possibilities, and realized that for him it would have to be the cinema or nothing. His reply to DeAngelis is important for understanding what he was trying to do at this early stage of his career:

I need a depth of field which perhaps only the cinema can give, and to see people and things from every side, and to be able to use the "cut" and the ellipsis, the dissolve and the interior monologue. Not, of course, that of Joyce, but rather that of Dos Passos. To take and to leave, inserting that which is around the fact or event and which is perhaps its remote origin. I can adapt the camera to my talents and the character will be pursued and haunted by it: contemporary anxiety derives precisely from this inability to escape the implacable eye of the lens.[6]

For the next forty years, in fact, Rossellini was to be faulted for not meeting the demands of a conventional narrative form whose own validity and "naturalness" would seldom be questioned. Though they overstate their case, especially for these early films, Aprà and Pistagnesi are right to insist:

What is so striking in the first three films, beyond their quality, which is actually quite modest, is that Rossellini has left behind the "strong" models of the classic cinema, that is, the propaganda films and the two examples of Luciano Serra, pilota and Uomini sul fondo . . . . In respect to these two models he makes a work of deconstruction, of disassembly , taking out of them the elements which make them "classic" films. For example, [Rossellini's] films, even though they tend toward narrative, are told "badly," with ellipses which often make the events obscure, or better, "incomplete." . . . Rossellini will often be accused of not knowing how to tell a story, but what is not noticed is that Rossellini wants to tell the story badly, because he is not interested in the plots but in the pauses, the moments of rest, the waiting, or certain contrasts between characters or between characters and the background, which manifest themselves only on the screen, not in the plot.[7]

This point of view is one I most emphatically share concerning the later films, including perhaps Paisan , but especially those made during the Ingrid Berg-

man era. For one thing, this penchant for narrating "badly" helps us to understand why Rossellini's films have always fared so poorly at the box office. The antinarrative elements of films like Un pilota ritorna , however, are only barely in evidence; Rossellini himself can hardly be said to be fully aware of them, or actively seeking to alter conventional techniques of cinematic narration. But they are there, seeds barely sprouted, of a new way of making films.