21—

General della Rovere

(1959)

As we have seen, Rossellini's own voyage to India had an enormous impact on his artistic sensibility and his view of what the cinema had to become. However, India was a box-office failure as well, and, in fact, represented one of the lowest financial points of his career. His situation in 1958 was thus an awkward one: he had yet to find the alternative financing of television that he would successfully exploit for the last fifteen years of his life, yet he no longer had the lure of Ingrid Bergman to insure a steady stream of prospective investors, ever hopeful for a hit.

There had always been offers to do films that were more overtly "commercial," though little documentation exists to tell us just what these projects were. The actor Vittorio Caprioli recounts how one night he and the producer Morris Ergas were having dinner with Rossellini and Sergio Amidei when Caprioli mentioned that Diego Fabbri had just finished writing La bugiarda for him and that Ergas should produce it. The eager Rossellini immediately suggested that he direct the picture, but Ergas said no. Amidei then mentioned a sketch by Indro Montanelli he had recently seen in the Milanese newspaper Corriere della Sera; Ergas and Rossellini expressed interest, and the film was on its way.[1]

Montanelli's sketch, followed closely in the film, tells the story of a petty thief and gambler who is forced by the Germans to masquerade as General della Rovere, an important Italian military leader and Resistance figure who has been secretly killed by the Germans while attempting a clandestine landing. Bertone, the gambler, is put in prison in order to discover the identity of the leader of the Resistance, for while the Germans know that they have him in the same jail, they do not know which prisoner he is. Bertone becomes so absorbed by the

role he is playing that at the end of the film he willingly goes before the firing squad with his "fellow" partisans rather than reveal the identity of their leader.

The screenplay was written principally by Amidei, Diego Fabbri, and Montanelli,[2] but it is unclear how closely it was followed by Rossellini. Just after the film was completed, the director was claiming rather grandly:

I don't need traditional methods to make a film. For me, the inspiration comes on the set. My work on the scenario of General della Rovere consisted in tracing out the general lines of my story and of imagining, very close up, the personality of my character. I have no preconceived notions before I begin filming, and it's the first shot of a film which determines the entire work. It is then that I really feel the rhythm that I must give it, which leads me to imagine the thousand things which are the essence of my film. I want to arrive at the film location with a new feeling.[3]

Five years later he bluntly insisted, that "The only thing that really existed of the film was the screenplay which I read quickly and then put aside during the shooting. Many people, including the producer, have taken credit for the organization of that film, but this is the real story."[4]

It is ironic that Rossellini should have been so intent on claiming authorship of a film that he so obviously disliked, both during production and later. It was not the last film he was to make out of sheer necessity, but it was the first. Even the rather forced humor of the Totò vehicle Dov'è la libertà? had been closer to his heart. Years later, in fact, he named General della Rovere as one of the two films (the other being Anima nera ) that he was actually ashamed of having made, because "it's an artificially constructed film, a professional film, and I never make professional films, rather what you might call experimental films."[5] In another interview conducted at the same time, he explained why he undertook the project in the first place, relating his motives to the new discoveries he had made about himself in India:

I had decided to change [my methods of filmmaking] completely. And so I said to myself: "In order to change and to put my new ideas into operation, I'll need at least six months, or a year," and so I tried to find something by which I could save my life. Well, there were a lot of people who were very happy that I had finally given in, that I had obeyed, that I was following the rules (though I wasn't). Instead, it took some five or six years to get started in a serious way, and that was a bad surprise.[6]

Even during he shooting he was uneasy. He told the interviewer for Arts magazine, "I would reproach my film for being too well constructed, for relying on the continuing development of the story." His enormous ambivalence shows, as he continues: "I'm afraid that my film is going to be a big success and, in spite of everything, I hope it will be. Was it perhaps a tactical error for me to have made it? I don't really know yet, because I'm still too much in it. I have been trying to imagine the pros and the cons, the dangers for the continuation of my research and the possibilities that it holds out to me. Let's wait and see.[7]

It is clear now that General della Rovere was not his kind of film, despite the superficial similarities to past successes that made some critics ecstatic that Rossellini had seen the light. Even Massimo Mida, who heralded the film as opening

up a renaissance in Italian cinema through its return to the past, and who saw in it the end of Rossellini's period of "involution," nevertheless realized that the director was unenthusiastic and that the final product was little more than a tired rehash of his earlier triumphs. Mida admits that General della Rovere "was not the film that Rossellini would have wanted to direct and was not, at that moment, his ideal film," and quotes instead a significant array of "projects closer to his heart": Brasilia, The Dialogues of Plato, The Death of Socrates, Tales From Merovingian Times, Bread in the World.[8] These titles indicate clearly where Rossellini wanted to be, and where, after a few more years of frustration, he would be.

Of all his films, it is only General della Rovere that can and must be judged by the conventional standards of the "well-made" film.[9] It is immediately likable in a way that many of his other films are not, but it contains barely a hint of the depth or resonance of a film like Voyage to Italy , say, and ultimately registers as little more than a bravura piece of acting. Rossellini had been able to prevent Bergman from "acting" through the sheer force of his will over her, but De Sica, an immensely successful star by this point (and as a director perhaps even more prestigious than Rossellini), could not be so easily restrained. Nor is it certain that Rossellini even tried to control him; having already accepted the idea and the script, he perhaps may have given in on this point as well. For Rossellini, "saving his life" took the form of reassuring producers that he could make a conventional film if he wanted to, making it clear in the process that the other films, however "poorly made" they seem on the surface, were, for better or worse, like that on purpose. In fact, General della Rovere contains more than a few excellent passages of conventional filmmaking that can stand with anything produced by the most "professional" of Hollywood directors.

One very significant aspect of the film is its return to the war and the Resistance, the scene of Rossellini's earlier victories. Strangely enough, it was one of the first Italian films to go back to that period, and in the wake of its financial success, a host of others quickly followed. At the time, Rossellini told a reporter for the New York Herald Tribune that he had returned to this subject because he felt "that it is necessary to re-introduce the great feelings that moved men when they were confronted face to face with final decisions."[10] In addition, there was now a whole new generation who needed to have these anti-Fascist values inculcated in them, young people who had had no direct experience of fascism. Unfortunately, these values have not been reinvigorated in the film and seem less than fresh. Rossellini's earlier theme of coralità reappears, but when mixed with his more recent emphasis on the individual, the result is a dynamic of leader and followers, which is closer than ever to the superficial psychologizing of the standard Hollywood product.

If General della Rovere marks a return to the content of the earlier films, in formal terms it is a return to the dramatic and narrative conventionality of Open City , not to the dedramatized distanciation of Paisan . Thus, the film's plot, narrative thrust, and suspense have all been greatly intensified. In this film, things definitely happen . Lots of things. Nor are the dramatic moments undercut, as usual in Rossellini's films, but are lingered upon and played for all

they are worth. Similarly, our relationship with the protagonist is now completely changed, and Rossellini's typical distance separating the spectator from the character, a distance that seemed to foster a morally preferable sympathy rather than a manipulative and emotionally constricting identification, now disappears. Some contemporary critics praised the increased psychological subtlety of the film's characters, and it is true that we get more time to come to "know them as people." The method of accomplishing this, however, is that of the banal film that relies on the transparent, "telling" detail to "reveal" characters, as when the German officer straightens his tie before receiving della Rovere's real wife at the prison. The "richness" of the psychological portraits is, in fact, based on an amassing of clichés. Other critics applauded the director's newfound sense of humor, but, again, it is a humor that is totally predictable and painlessly digestible, accompanied by little wit and less irony.

Rossellini went even further to make his new backers happy. According to Variety , the entire film was shot in thirty-one days for a mere $300,000.[11] Rossellini later said that, even though he had been given twelve weeks for the shooting, he began July 3 and took the finished, edited film to the Venice film festival on August 24![12] And the reward for his capitulation? General della Rovere was awarded the Golden Lion (along with Mario Monicelli's La grande guerra ) at the festival, and in its initial release grossed over 650 million lire, more than forty times the box-office receipts of Voyage to Italy .

Professional, "accomplished," a well-made, if rather straightforward, adventure story of the Resistance. But is it? As one might expect from a film by Rossellini, all is not what it appears on the surface: "They thought I had given in, that I had obeyed, that I had followed the rules (which I hadn't.)" In spite of the work's apparent seamlessness and conventionality, in other words, there remain recalcitrant elements that refuse to fit. These elements have proven particularly frustrating for critics bent on finding organic unity, especially since they occur in a work that seems so utterly direct and obvious. First, there is the film's blatant artificiality, especially in terms of its lighting and its sets. The lighting, for example, is cast in the stylized film noir mode of a movie like Fear , rather than the serviceable, "natural" flatness of Open City . Furthermore, Rossellini is now shooting in a studio, and the familiar rubble has been manufactured by his crew. The sets are not obviously artificial, of course; they are, simply, just not real. Of a piece with the slickness of the rest of the production, they are in fact "well done," and one critic even complimented Rossellini on doing a better job at capturing the "true" Milan on a Roman studio set than any other director had been able to do in the real city.

Again, there is a strange dynamic at work. For, intercut within the scenes shot in the studio (often by means of a wipe, an ostensibly more "artificial" means of transition that is used much more frequently in this film than in his previous films), we are shown real footage, or at least "real" in the sense of taking place in a real, preexistent location: marching soldiers, bombing raids, the landing of the true General della Rovere via a submarine and a raft (a sequence shot by the director's son, Renzo), and the truck on the road. Events depicted in this "real" footage happen with the quickness that in Paisan added powerfully to the sense of seeing a real event happen before our eyes. There are

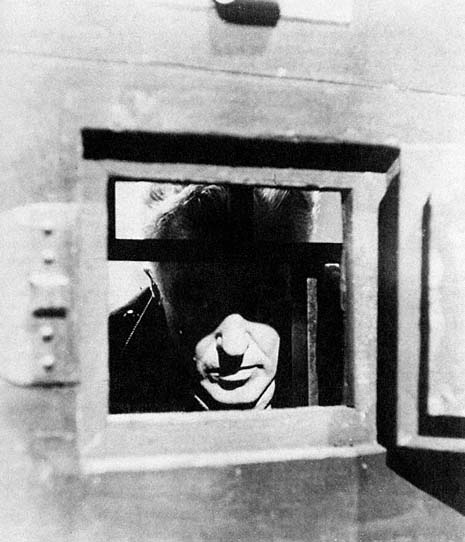

A "well-made film": Vittorio De Sica peers out from his

jail cell in General della Rovere (1959).

also moments early in the film where presumably "real" people, that is, non-actors seemingly unaware of the camera's presence, are standing around watching wrecking crews knock down actual bombed-out buildings, in a De Chirico—like reprise of early scenes from Germany, Year Zero . All of this contrasts continuously with the blatant unreality (because so tidy and managed ) of the studio locations, especially the unconvincing bombing raid on the prison.[13] The result, once more, is an extension of that revelatory dialectic, in muted form, that we saw at work earlier between the conventions of cinematic realism and the de-

piction of reality itself. Here, however, the film's code of realism is not threatened or invigorated by any perception of the potentially dangerous incursion of this reality. Hence, the clash of the footage shot on the set and those few bits shot on location is more reminiscent of the comic self-reflexivity of La macchina ammazzacattivi than of the exciting, unstable mixtures of Paisan . At the same time, the dominance of the code of realism in this film affirms the utter impossibility of a true return to the earlier films, no matter how devoutly wished by the director's supporters, at least in anything other than an ironic or self-aware mode.[14]

Yet even this minor disjuncture between realism and reality operates thematically in General della Rovere . One scene, for example, when a group of partisans still at liberty meets specifically to discuss whether or not the man in prison is the true della Rovere, is shot using rear projection, with actual snowy streets and a bombed-out church serving as background to their meeting. Since the rear projection is rather unsteady, however, the artificiality of the scene is foregrounded, thus raising the same question of appearance and reality that is at the center of the partisans' discussion. Furthermore, what General della Rovere openly problematizes is the nature of the self and the reality of identity, and thus serves in an indirect way to extend patterns we have seen operating in Una voce umana and the "Ingrid Bergman" segment of Siamo donne . Just as Magnani's status as actress was foregrounded in Una voce umana , so, too, what we are not allowed to forget here is Vittorio De Sica as actor, playing a role. De Sica, the well-known actor and director, is playing a down-on-his-luck con man named Bertone. Bertone, for increased credibility with the families of the interned men he is trying to help (while helping himself financially) masquerades as a certain Colonel Grimaldi. When he is arrested by the Nazis and made to work for them (significantly, the Nazis want him to discover the identity of a Resistance leader), De Sica/Bertone/Grimaldi steps into his greatest role, that of General della Rovere, which he assumes so completely that he dies. Again, the abîme of representation and the self opens up at our feet as the continuity and certainty of self-identity seem to be threatened. Which is the real man?[15]

These complications reach their peak in the final scene. It would seem that the one thing that can ground this endless play of selves, of appearance and reality, is death. But, in fact, death does not resolve or explain the ongoing displacement, but only halts it, in the most purely functional and banal manner. At the end we are still utterly in the dark concerning Bertone's motives. Some critics have seen his decision to die with the partisans as a decision to end his own rhetoric and the falsity that has defined him since the beginning. It seems equally plausible, however, to view his death as the apotheosis of self-deluding rhetoric, his final histrionic moment, since in terms of the logic of the narrative, he could have told the German officer that he had not been able to discover the true identify of the sought-after leader of the Resistance.

Perhaps most annoyingly to recent Italian commentators, the film is politically ambiguous as well. As in Open City , the Italian Fascists are barely portrayed at all; they parade by in the first few seconds of the film singing their marching song "Camice nere," but this seems to serve more as a historical

marker than anything else. Thus, Italians are again seen only as victims, as when Bertone first encounters the German officer and struggles to find the most ingratiating answers to his questions, rather than the perpetrators they also were. In addition, while generally pleased that Rossellini has softened or even subverted Montanelli's consistent glorification of militaristic and nationalistic values (for example, when Rossellini has Bertone's final courageous resolution spring from the resolve of the others rather than himself), many leftist critics have felt that too many traces of these values remain in the dramatic structure of the film. And it is difficult to disagree. For one thing, the politically progressive figures in the film are portrayed as weak, in need of a strong leader to calm them, like children, during the bombing attacks. Clearly from an aristocratic class, della Rovere is "born to lead," and when he shouts, "Long live Italy!" and "Long live the king!" he unequivocally aligns himself with the military caste. Bertone's change of heart, furthermore, is clearly an ahistorical moral decision rather than one based on a greater understanding of the ideas and ideals of the Resistance, and is related to a certain conflation of religion and the fatherland espoused by Montanelli and his followers. Thus, for Guido Aristarco, perhaps the foremost Communist film theorist in Italy, the film fails because it does not put Bertone's change of heart in a sociohistorical context: if Bertone's idea of the patria were examined critically, Aristarco insists, we might have a better idea why there was such a rush to reestablish the traditional pre-Fascist state after the war.[16] Bertone says he does it out of "duty," but duty is a nonspecific value that can be felt as much by a Fascist as by an anti-Fascist. The ultimate Marxist complaint, then, is that the Fascist past is seen by modern audiences as merely "a moment of human wickedness," in Lino Miccichè's phrase, that all right-thinking men joined to combat: "A prisoner of his Montanellian character, the director made of him a symbol of an anti-Fascist vision which oscillated continually between a vague humanism of the feelings and a cunning and nebulous ethic of 'duty,' almost as if the struggle against fascism had been a question of abstract moral debate rather than a concrete political choice."[17]

This is closely related to the complaint that a new generation of Marxist critics has lodged, not unconvincingly, against Open City and Paisan . Unfortunately, it seems to be the only real link between General della Rovere and the successes of the past, now fifteen years distant.