20—

India

(1958)

By the mid-fifties Rossellini's career had reached rock bottom. His films with Ingrid Bergman had not only failed at the box office, but had failed critically as well. True, the French were calling them the heralds of a new age of filmmaking, but the people with the money were not listening. As we saw in the last chapter, Bergman, too, was growing dissatisfied with being Rossellini's "property." Nor was he insensitive to their problems, as he explained many years later:

That was a very particular moment in my life, because I was married to a great, great actress. The point was that I risked too much and we were hated, I don't know why. Our films were not at all successful and we had big problems as we had three children. She was aware of the problems and she thought it would be wise to return to the industry just in order to save the material means of our life. I appreciated that thought very much, I believed it was wise. Unfortunately I was absolutely unwise myself and I did not want to be the husband of a great star. So very peacefully, very quietly and with a very full understanding and tremendous human compassion we decided to break. It was very hard, because we loved each other and we had three children. It was very, very painful.[1]

Now at his personal and professional nadir, Rossellini traveled to Africa, South America, and finally, in June of 1956, to Jamaica, where he was to make "The Sea Wife" with Richard Burton and Joan Collins. On his arrival in Jamaica, however, he discovered that the producers had changed the script he had written, presumably to avoid censorship problems; Rossellini immediately abandoned the project. (It was subsequently filmed by Bob McNaughton and released in 1957.)

Then the idea of going to India occurred to him. As he told reporters in Paris:

The producers don't want to give me any more work because what I'm saying doesn't interest them any more. That's why I accepted the offer made by the Indian cinema. I have been given carte blanche: in India I'll be able to study the atmosphere, analyze the major problems, make the most of the magic, fakirist and philosophic tradition, juxtaposing it with contemporary voices which are rising and becoming important. It will be, in short, the great Indian civilization, in all its grandness, its past and future which will take me by the hand and trace the subject which has not in any way been imposed on me. It will be difficult to be a neorealist in such a fabulous atmosphere, but I will certainly find many similarities with things I have already treated while developing Italian themes.[2]

It must be remembered that these remarks were made for the benefit of the press and seem intended to pander to their perhaps less-nuanced sense of things—in film journals, for example, Rossellini had been denying for years that he was a neorealist. Nevertheless, the remarks offer an interesting summary of his thoughts as he was about to depart for India. He had always been fascinated by foreign cultures, but by this time he was becoming especially interested in what was beginning to be called the third world. Here he could closely examine a single traditional culture, but, more importantly in view of his later overwhelming interest in science and modern technology, he could try to depict a vibrant test case, an actual battlefield between tradition and technology. He was also immensely drawn to Ghandi, who had once stayed in his home in Rome for a few days, and he told Victoria Schultz in Film Culture that "Ghandi was the only completely wise human being in our time of history."[3] He was also impressed by Nehru, Ghandi's successor, and spoke of him as "an extraordinary man" and "a saint." Jean Herman, Rossellini's young French assistant, makes it quite clear in the article he wrote for Cahiers du cinéma during the filming that the final product was to be a kind of social analysis of India, and certainly not merely the personal impressions of an auteur: "This will be the objective summing-up of ten years of freedom, of ten years of work, and of all the snares and traps that lie in wait for India today."[4]

Rossellini told a reporter for the New York Sunday News that this new film was to be "a takeoff on one of my earlier films, Paisan , which made money in the United States,"[5] and, in fact, the films are similar in their episodic structure and method of filmmaking. In India, as in postwar Italy, Rossellini went from one end of the country to the other, filming interesting sights, on the lookout for promising material. As Herman tells us, the director came to India with the rough outline of an idea in his head, but, as always, he allowed the specifics of the events, people, and places he encountered to determine the final product, making him add, delete, and change continuously.[6] Another aspect of his filmmaking practice here that is important for his later career is the fact that the project originally took the form of short documentary films for Italian and French television, from which he would then cull the best material for release as a commercial film. At this point, however, Rossellini still sees television princi-

pally as a means to an end, a kind of dry run (and source of necessary funds) for what he really wanted to do.

A further similarity with his earlier, pre-Bergman practice, is his insistence on the incorporation of "real life" into his film. As in films as chronologically far apart as La nave bianca and Francesco , he tells us proudly in the titles of India (the film is also widely known as India '58 ) that "the actors, all nonprofessional, were chosen in the very locations in which the action takes place." To some extent the result is again, paradoxically, to destabilize the codes of realism, preventing our acquiescence in the illusion and always keeping before us the sense that what we are seeing has been made . He also returned to his previously standard practice of observing someone he might choose to be in the film in order to memorize his "natural" actions, then, when he became stiff and artificial in front of the camera, Rossellini would "build him up again, teach him to act the way he was before you began teaching him to act."[7] He was so taken by the successful adaptation of his old methods to a new subject matter that he told the French journal Cinéma 59 that his future plans extended to South America, especially Brazil and Mexico. His remarks clearly foreshadow the great didactic project to come:

I will send teams of young people into each country, and they'll do an initial scouting. They will include a writer, a photographer, a sound man, and a filmmaker, who will be the head of the team. And this is how I'll proceed: I'll make an index for each country, and I'll study, along with my collaborators, their problems, food, agriculture, animal raising, languages, environment, etc. As you see, the task of a geographer and ethnographer. But it won't remain merely scientific, and will give each spectator the possibility of discovery. The art will only be the end point of this preliminary work. My job will be to make a work which will be a poetic synthesis for each country. . . .

I have tried to use this method abroad, but I could also use it in Europe. I've returned from India with a new way of looking at things. Wouldn't it be interesting to make ethnographic films on Paris or Rome? For example, a wedding ceremony. . . . Well, we need to rediscover the rites on which our society rests, with the fresh outlook of an explorer who is describing the customs of the so-called primitive tribes.[8]

The relation of this film to the rest of Rossellini's oeuvre is complex. Before it come the intensely introspective, expressionist fiction films made with Bergman, which seem to make only the slightest nod of acknowledgment toward external, surface reality. Immediately after it come the films of the only really blatant, self-consciously commercial period in his life, beginning with General della Rovere (1959) and ending with Anima nera and "Illibatezza" (both 1962). Yet Jean Herman is correct, I think, in regarding India as a "synthesis of the Rossellini oeuvre" that merges the exteriority of Paisan with the interiority of Voyage to Italy .[9] India itself, as Rossellini pointed out, is an amalgam of these two realities:

The Indian view of man seems to me to be quite perfect and rational. It's wrong to say that it is a mystical conception of life, and it's wrong to say that it isn't. The truth of the matter is this: in India, thought attempts to achieve

complete rationality, and so man is seen as he is, biologically and scientifically. Mysticism is also a part of man. In an emotive sense mysticism is perhaps the highest expression of man. . . . All Indian thought, which seems so mystical, is indeed mystical, but it's also profoundly rational. We ought to remember that the mathematical figure nought was invented in India, and the nought is both the most rational and the most metaphysical thing there is.[10]

In this remark Rossellini is clearly trying to reinscribe the fantasy (here, mysticism) of La macchina ammazzacattivi and Dov'è la libertà? into a wider, now more inclusive, realist aesthetic. Instead of being opposed, fantasy will now become a subset not of realism, exactly, but of rationalism. This latter term, which in some ways will help Rossellini elide the contradictions of realism, will soon come to be paramount in his remaining films.

Rossellini's understanding of India is accomplished in four individual episodes, each with its own main "character," "story," and location, the whole bounded on both ends by a factual frame that, especially at the beginning, provides the information necessary to put the individual episodes in an overall context. (In itself, the episodic, fragmented nature of the film implies that our understanding can be only partial and fragmented.) An interesting, active dynamic is immediately set up between the frame sequence, which is marked by fast cutting, zooms, and quick camera movements—obviously appropriate to its concentration on the city life in Bombay—and the inner sequences of life in the villages, which are generally much slower, comprised primarily of long takes, medium shots, pans, and minimal cutting. Appropriately, the physical movement which the film celebrates is registered in two different ways, depending on location. In the opening urban sequence it is conveyed through the artificial excitement of montage. Where movement exists in more natural settings, however—for example the flight of birds and the scurrying of monkeys through the forest—it is also highlighted, but significantly, by following it through pans.

Our own movement, from the frame to the interior stories and back again, is itself thematic. The voice-over tells us in a dramatically heightened, pulsating way at the very beginning of the film that "the first thing that astonishes you [in Bombay] is the crowd: tens, hundreds, thousands, tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, perhaps a million people who come together like the incessant current of a river." Rossellini seems to be suggesting that, while first impressions are important, they must be seen through, in order to come to any understanding of the reality of the country. Yet, at the very end of the film, after the four internal, personalized stories have been told, we are put back in the same place, back into the middle of the city that we have not seen since the beginning, back into the fast cutting and zooming on the mass of swarming humanity, while the voice-over murmurs, as though mesmerized, one last phrase: "And still, the crowds, the immense crowds." We wonder if we, as outsiders, are forever condemned to be prisoners of our first impressions, which of course are always a product of our own culture, the culture we thought we left behind.

The dynamic between the framing sequence and the internal sequences also underlines the presence of the filmmaker in the whole process. In the opening sequence of India , a thoroughly un-Rossellinian style of editing assails the viewer: the cutting is even faster, and more self-conscious, than it was in the early La

nave bianca , so indebted to Eisenstein. While the voice-over bombards us with facts, the very presence of the massive statistics, despite their "objectivity," paradoxically seems to underline the fact that they were compiled and put together by someone , and thus from a particular point of view. At the same time, the visuals jump along quickly, often cutting in perfect unison with the verbal sound track (for example, in the exciting series of quick cuts that accompanies a string of rhyming verbs), further underlining the presence of a mediating mind. In the inner sequences, on the other hand, there are moments of quick cutting when the narrative demands it, but the sequences are primarily composed of long-take shots by an absolutely immobile camera. Here we see simple acts, like the ritual bath of a young engineer, or the attachment of a log to a chain, then the chain to an elephant—acts often long and drawn-out, unquestionably real—that are accomplished in a single take. (Also, of course, the lack of cutting is appropriate to the subject—in this case the elephants, the effect of whose ponderous, immense bobbing would be totally lost if the sequence were fragmented into a jazzy montage.) Though these inner sequences sometimes seem to offer themselves as privileged, direct glimpses of a "true" reality, the fictionalization of the episodes, as well as the return of the frame tale at the end, work against this.

The manner of presenting the inner tales and their information is complicated as well, for once they have been factually and contextually launched by a third-person voice-over, all, in one way or another, are told from a first-person point of view. Thus, each episode seems to be balanced between the desire to convey a certain amount of abstract information and the related, but different, desire to put this information in a human context. Though one might object that the individualizing of the portraits takes away from the typicality of the film as a documentary, it is clear that seeing things from a single individual's point of view, and, even more importantly, hearing "his" words (in Italian, of course) concerning that reality is what makes the film so memorable. The language used by each principal character is so utterly direct and spare that it carries the charge of a poem by William Carlos Williams. The old man of the third episode, for example, tells us in a stately, measured tone (with enormous pauses between most of the sentences and accompanied by a perfect correlation between the words and pictures):

I am eighty years old. I have always lived here but the forest is still rich, appealing and full of secrets. Especially at night when it resounds with the fantastic love songs of the tigers. The jungle is the temple in which their rites of love are celebrated. When I awake at the rays of the sun, there is an explosion of joy which surrounds me. My wife and I do not need to exchange many words. Our gestures and looks are enough to express our unchangeable, daily solidarity. It has been a long time, after all, that our mutual duties have been shared between us. What else is there to say?

The entire film, in other words, has been subjectivized, and on several levels at once. The filmmaker has, for his part, made an attempt at objectivity, at getting beyond the Western self: Claude Baurdet, a reporter for France Observateur , wrote at the time, "The director insisted that he needed an intermediary with a true understanding of the lives of the Indian peasants, in addition to cinematic

knowledge, in order to complete his project."[11] Rossellini also knew, however, and freely admitted, that everything that we see in the film, no matter how objectively obtained, has been filtered through his own (Western) consciousness. He told Godard in a famous interview for Arts (which Rossellini later claimed Godard had made up) not that the audience should learn the truth of India, but that they "should leave the theater with the same impression that I had while I was in India."[12] As a reporter for the New York Times pointed out, the film is successful precisely because Rossellini was so forthright about his own romantic notions concerning India, and he quotes the director to the effect that his ideas about the country were "gathered from books and newspapers . . . [and] are a rather stewy mixture of Ghandism, passive resistance, Jawaharlal Nehru, land distribution, the five-year plan, and spiritualism."[13] Even more important in this regard is the self-consciousness apparent in the title of the television series itself: in Italy, where it was broadcast between January and March 1958 in ten episodes of eighteen to twenty-nine minutes each, it was called "L'India vista da Rossellini" (India Seen by Rossellini), and in France, where it was shown between January and August of the following year, it was called "J'ai fait un beau voyage" ("I Had a Fine Trip"); in both cases, the mediation of the filmmaker's consciousness is clearly signaled.[14]

In important ways, then, this entire film stands opposed to the prevailing film fashion of the time, cinéma vérité. Rossellini felt, for one thing, that this kind of "direct cinema" could never achieve anything more than an undigested depiction of a not necessarily significant surface reality. He told the editors of Cahiers du cinéma in a 1963 interview that, unlike the cinéma vériste who forgets that the camera is only a tool, the real artist is one

with a precise position, his own artistic dream, a personal emotion, who gets an emotion from an object and tries to reproduce it at any cost, who tries, even if he has to deform the original object, to communicate to someone else perhaps less sensitive, less subtle, his own emotion. You can see how the author enters into all this, how his choice is determined, how his style becomes the essential element of expression.

He spoke of being upset, bored, and angry at the screening of his friend Jean Rouch's La Punition , and when asked how his own film differs from cinéma vérité, he responded: "There is an enormous difference. India is a choice. It's the attempt to be as honest as possible, but with a very precise judgment. Or, at least, if there's no judgment, with a very precise love . Not indifference, in any case. I can feel myself attracted by things, or repulsed by them. But I can never say: I'm not taking sides. It's impossible!"[15] As we shall see, Rossellini forgets the impossibility of not taking sides when his subjects become historical figures. Here in India , however, he understands the problem full well, and as Bruno Torri has explained, the film was clearly meant to be "a harmonious and life-giving account of the interaction between what was observed and the point of view of the observer."[16]

Another site of the film's self-awareness is its fascination with rhythm of all sorts, visual, verbal, musical, and thematic, which Rondolino attributes to Rossellini's recent experience with opera and especially with the oratorio Giovanna

d'Arco al rogo . A marvelous correlation exists between the visuals and the sound track (both its verbal and its musical components) that seems unique in Rossellini's films, and this rhythm provides the pleasure inherent in all forms of rhyming, repetition, and fulfilled expectations. The musical score itself stands out, but for once in a Rossellini film, not because it is annoying; composed almost solely of various forms of native Indian music, it seems utterly organic to what we are seeing. The score is augmented and complemented by sounds that come from the location—thus, the bells worn by the elephants insist on the immensity of these animals' presence in the sound track as well. (Herman tells us that the bells are put on the elephants because the animals are so quiet moving through the jungle that a human could easily be hurt without some advance warning.)

The voice-over commentary (anathema to cinéma vérité) also reminds us that the film was made from a particular point of view, but once the basic information is presented in the opening sequence, it becomes less obvious. Rossellini had, in fact, told the reporter for the New York Times in 1957 that the images were more important than understanding the dialogue, for "a healthy picture did not need more than a little bit of explanation here and there." However, those few who have been lucky enough to see the only copy available in the United States—an unsubtitled black-and-white print owned by the Pacific Film Archives at the University of California at Berkeley—know how important the Italian voice-over actually is to a basic comprehension of what is going on. It would be more accurate to say that, once the basics of the narrative line of each episode are grasped through the commentary, the images supply a resonance of their own that transcends the merely verbal.

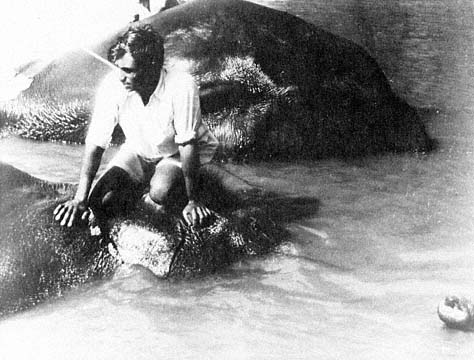

India 's emphasis upon the image is accompanied by a greatly enhanced sense of pleasure in composition that we last saw in some of the stylized sequences of Fear . Throughout his life Rossellini maintained that he was completely uninterested in "pretty pictures," and that, in fact, he always avoided them, but the evidence of India , at least, belies this claim. Many images are obviously meant to be experienced aesthetically rather than merely as neutral carriers of information. The best example is perhaps the astounding shot of the young engineer who takes his ritual bath in the artificial lake created by the dam he has helped to construct; the confluence of ancient tradition and modern technology is obviously the point of the shot, but our pleasure goes beyond this realization. The camera holds absolutely steady for what seems like minutes, creating a frame that is split in two by an unbroken horizon line, above which lies the untroubled sky, below the water, below that the land. The young man walks out into the water after shedding part of his clothes, bathes, then walks back onto the shore, picking up his clothes and walking out of the shot before there is a cut or a single movement of the camera. Examples such as this could be multiplied many times.

Let us now turn to a closer examination of the individual episodes of the film. The old themes are still present: for example, the concern with problems of communication and the attendant respect for diverse cultures are in evidence right from the opening title which, in an attempt to avoid a reductive Western "orientalism," shows the name of the film (and the name of the country) in Ital-

The elephant-bathing sequence from India (1958).

ian and English, in Urdu, and with the words, Matri Bhumi (Mother Earth), occupying the third position. Many conversations not absolutely crucial either narratively or informationally are presented at various times in three of the official native languages of India. The animal motif, so closely connected in his earlier films with the woman-as-victim theme, also reappears, but now it represents the relation between man and nature. In the terms of the perhaps too-neat formulation he gave Godard, "I wanted to show [in Fear ] what there is of the animal in intelligence, and in India '58 , I showed what there is of intelligence in the behavior of an animal."[17]

The first fully developed episode, which takes place in the jungle of Karapur and centers on the relation between the professional elephant drivers and their elephants, is a visual delight. We learn that "the elephant is India's bulldozer," and chuckle to see the elephants knock trees down and then carry them away. The narration switches to the first-person point of view of one of the drivers, who tells us how much elephants have to be fed, and, in a superb sequence, we witness the care that has to be taken every day to give the elephants their baths when it becomes too hot to work any longer. The elephants loll and roll over in the water, as languorous as immense cats. When a company of puppet players arrives in the village, the young man becomes interested in the owner's daughter, and from this moment on, the elephants (who are also "falling in

love") and the two young people are overtly compared in order to point up the harmony between man and nature that Rossellini finds in India. The young man goes to the schoolteacher for a formal letter to his father, asking him to speak to the girl's father in order to arrange their marriage. This scene and the one following (of the schoolteacher acting as mediator between the two fathers) are recorded entirely in the Indian language of the region, with no specific explanation provided in Italian. By the end of the episode, the young man tells us that the pregnant elephant must go away from the male halfway through her pregnancy, in the company of another female elephant who will minister to her needs, and because the demands of his work do not allow him to accompany his pregnant wife to her mother's, she, too, must be accompanied by another female.

The second episode, like the rest, begins with specific information that later will be put in more personal, individualized terms. Here the emphasis is on water. We start at the Himalayas, India's principal source of water, and learn about reincarnation, the sacredness of the Ganges, and the holy city of Benares along the way. The central focus of the episode, however, is the immense dam built at Hirakud, largely by grueling human labor. Our protagonist is a young engineer who has been working on the dam for seven years but who must now leave because his job is finished. He and his wife, we learn later, were originally refugees from East Bengal, due to the division of Pakistan, and since their child was born at Hirakud, they have come to look upon it as home. The husband seems sad but reconciled to the prospect of moving, but the wife complains throughout, refusing to understand, and at one point after a farewell party, an argument breaks out that ends with him pushing her violently to the floor.

The emphasis throughout is on the engineer's consciousness, and it is clear that this episode of the film, though visually magnificent, depends heavily on its verbal component to be understood. The young man makes one more trip back to the dam, where thousands upon thousands of unskilled workers—mostly women—carry rocks and dirt atop their heads, basket by basket, in their seemingly Sisyphean task. We learn from the engineer's voice-over narration that some 435,000 people work at the job site, and 175 died building the dam. But, "Before with the floods, if we had to build a monument to the dead, it would have taken a list as long as the dam itself to inscribe the names of all of them."

The chief theme of this sequence is the advent of technology into a traditional culture. Rossellini clearly believes in technology—and this belief will increase dramatically as the years go by—but at this point he is still concerned about its misuse. As Jean Herman tells us at the end of his article:

Rossellini came here with his head stuffed with questions. He was afraid of the dangers represented by the [West's] too-clean-hygiene, the button-you-press-which-solves-all-your-problems, the books-on-how-to-teach-five-year-olds-in-five-days, the pills-which-save-you-from-eating.[18]

The director is clearly fascinated by the conflict raging in the mind of this young engineer between the desirability of modern technology and the demands of the traditional culture. In one powerful sequence the man is wandering amid the giant spools of electric cable and immense electrical transformers, and, in a voice made to reverberate like an echo chamber, he thinks: "Electricity. Magic.

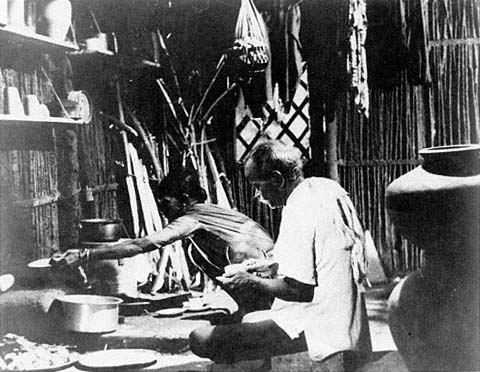

The old man and his wife eat breakfast in a scene from India .

Everything can be explained. All it takes is to think. There is no magic. There are no more miracles. Knowledge. Mystery. No more mystery. Knowledge. Hirakud." In the next sequence, however, we are pulled in the opposite direction as he observes a ritual burning of a body on a funeral pyre and thinks aloud that, while death is difficult for those who have been left behind, it must be very good to be able to dissolve completely into nature. A satisfying synthesis is achieved in the shot described earlier, when the young man takes his ritual bath in the artificial lake that has been created by the dam. The family leaves the next day with the cart carrying the few pieces of their furniture; stretched out behind them is the overwhelming presence of the dam. The episode ends with a resonant, self-consciously composed shot of a file of workers moving off to the right, who are rhymed visually by different-colored stones in the curb in front of them; the camera pans right, away from the couple, to "discover" the workers, then remains immobile as they file out of the frame, one by one.

In the third episode we move to the land where the rice grows. Our protagonist here is an old man who we see in his daily rituals: making obeisance to the sun when he rises, having breakfast with his wife, giving advice to his sons. We see vaguely "documentary" material that serves to advance the narrative not a whit, like a woman breast-feeding her infant, and the old man's wife packing

the sides of their hut with mud, reminiscent of similarly "aimless" sequences as far back as La nave bianca . The old man tells us, in a soft-spoken, simple prose that is thoroughly convincing:

The only thing that is left in me is the need for contemplation and for that there is only one place on earth that can satisfy me: the jungle. I love my cows. They are beautiful and strong animals. I always bring them with me. . . .

When I am alone in the jungle I feel strongly the presence of nature and it seems to me that little by little I become part of it.

He says that, even though he knows that the tiger he hears will not hurt him, still he is afraid.

Then one day his jungle peace is destroyed by the presence of three trucks full of men looking for iron; the old man has often heard of this substance, but believes it is a myth. And here Rossellini shows us the less pleasing side of technology. The noise of the motors causes all the animals to become upset (monkeys and vultures are juxtaposed in the editing in a clear foreshadowing of the next episode); in the commotion, the tiger is attacked by the porcupine, and, as the old man knows too well, only a wounded tiger is ever dangerous. The tiger finally does attack a man, as the old man feared; the cycle is complete when the prospectors decide to go on a tiger hunt for this dangerous animal. The old man asks, "Why kill? Isn't the world big enough for everybody?" In the last sequence of the episode, he sets a fire to convince the tiger to seek refuge in another part of the jungle, away from the hunters.

In the final segment Rossellini moves completely into the world of the animals by making one his protagonist. Again, a problem is posed and a piece of information supplied; this time it is the inverse of the water of the second episode—the devastating effects of drought. The camera tilts down from the "sky of steel" to reveal a man and his trained female monkey wandering through the parched desert. The man collapses and, as he slowly dies, the monkey tries vainly to protect him from the vultures that are gathering to attack. The sequence becomes a veritable feast of camera "trickery," with rhythmic pans, faked shadows, and suggestive editing all used to exacerbate the sense of danger. The sequence continues much longer than one might normally expect of a wordless event like this, and the effect is to make us even more aware of the elaborate rhythmic choreography of camera, physical shapes, light and shadow. In a chilling image, vultures bounce along the ground, their enormously long wings fully outstretched, but seemingly more in order to frighten than to propel them into the air. The monkey finally gives up her quixotic act of protecting her dead master and breaks loose from the chain that holds her, as the editing becomes faster and faster and the vultures close in—again, all through the suggestivity of the cutting rather than through any actual proximity between the monkey's master and the vultures about to attack.

This sequence is followed by a quick cut to the fair toward which the man had been traveling when he collapsed. Characteristically, we are not told that this cut signifies the continuation of the monkey's narrative; we do not see her or hear of her, in fact, until the location and the environment of the fair have been fully placed before us. Only after many shots of the various performers

does the monkey come into the frame, and we are left with the impression, as always, that the individual story is not important in itself, but only as a vehicle for presenting whatever reality has been found and/or constructed in the encounter between the filmmaker and the country. Then the film cuts suddenly to furious cart-and-oxen races, which apparently are part of the fair but, again, are narratively unmotivated and remain unexplained by the laconic voice-over.

The monkey has come to the fair out of training or instinct and, lacking a master, pitifully goes through her paces, doing what "she is used to doing, picking up coins that she does not understand the use of." She is unable to provide for herself because she has lost her connection with nature, and, at the same time, wild monkeys threaten her because she is deeply tainted with the smell of man. We see unhappy shots of her sleeping on the temple steps like a bum, forlorn and hungry, while her more natural relatives send up a howl at her presence. Finally, she is rescued by a new owner, and the last image we see of her is in her "new life" as a performer on a miniature trapeze. The voice-over gives only the barest information and is painfully reticent and noncommittal about how we are to read this image of her swinging back and forth above the awed crowd. Again characteristically, Rossellini refuses to move to a simplistic closure regarding this final example of the relationship between man and animal. Most viewers will find the image degrading, I think, and while we may have been intended to take this training as one more example of the wonder of man's skills, the monkey seems to represent a message counter to that which has gone before. Man and animal, and by extension all of nature, are in close harmony in India, but the two realms are distinct, finally, and must remain so. The monkey is awkwardly suspended between the world of men and the world of animals, and not comfortable or even able to take care of herself in either one. The monkey's split between nature and culture is, however, emblematic of the human condition, Rossellini seems to imply, especially in terms of advancing technology. In fact, in the 1959 Cahiers du cinéma interview he said, cryptically, that the monkey's division is "exactly the story of all of us. It's the battle that we're engaged in." The episode ends immediately after this shot, with a close-up on the human faces that file past the camera on their way out of the small circus tent. We then go back suddenly to the final short piece of the framing sequence, which completes the decisive return to human beings. For Rossellini the humanist, it is good that men and animals can be in such a harmonious relationship, finally, because it is good for men.

The film was first presented at the 1959 Cannes festival, out of competition, and was well received; its commercial release in Italy did not come until June 1960, however, and by April 1961, the film had grossed only 15 million lire—another box-office failure. This time, at least, the general critical reaction was favorable. The French appreciated the film, of course, especially Godard:

India goes against all standard cinema: the image is only the complement of the idea which provokes it. India is a film of an absolute logic, more socratic than Socrates. Each image is beautiful, not because it is beautiful in itself, like a shot from Que Viva Mexico , but because it's the splendor of the true, and because Rossellini takes off from the truth. He has already departed from the place most others won't even reach for another twenty years. India gathers

together the entire world cinema, like the theories of Reimann and Planck gather up geometry and classical physics. In a forthcoming issue, I will show why India is the creation of the world.[19]

Even Rossellini's most bitter Italian critics, those who had pilloried him during the Bergman era, welcomed him back to the fold, anxious to "forgive" him. In Mida's words, "with a wipe of the sponge, he has wiped out all the earlier mistakes, all the uncertainties of an obvious decadence."[20] More recent critics, like Baldelli, however, have mounted a serious attack:

The eye isn't enough when an exact politico-cultural preparation and a complete immersion in the circumstances are lacking. Rossellini shortens and at the same time confuses the historical distances from the moment he begins to see India as a gigantic example of his usual themes: a boundless South crawling with "paisans" and the fabulous presence of antique temples, a remote past which is always equal to itself, a perpetual seat of equilibrium between nature and history.

He complains that Rossellini shows the irresistible, harmonious onward march of technology that in actuality proceeds at the expense of the masses. He faults Rossellini's devotion to the passive nonviolence of Gandhism, the whole film becoming, for Baldelli, little more than a transference of the ideals of Saint Francis to the Indian masses. Finally, he objects to the film's neglect of topics like starvation, the caste system, religious superstition, and the inability of the masses to read.[21]

Of course, Baldelli is right. Seeing the film, however, is a profound and moving experience that perhaps covers up, but also redeems all its shortcomings at the same time. Of the films of Rossellini's that are not available for public viewing, this is perhaps the greatest loss, not only for the proper understanding of Rossellini's career, but for the proper understanding of the potential of cinema itself. Andrew Sarris has called it "one of the prodigious achievements of this century,"[22] and he is only overstating by a little.

Before concluding this chapter, it may be useful to describe in more detail the major shift that was taking place in Rossellini's thinking at the time, which is signaled by the new emphases, especially on technology, apparent in India . The principal text will be his interview with Fereydoun Hoveyda and Jacques Rivette published in the April 1959 issue of Cahiers du cinéma . It is here that the director first spells out his increasing interest in the powers of human reason, an interest that will remain submerged in the more blatantly commercial films that immediately follow, but will soon after become nearly obsessive.

In the interview he professes first of all to be amazed that modern abstract art could have become the "official art," given that it is the least intelligible. The reason for this, he believes, is that man is being forgotten, that he is becoming just a cog in a gigantic wheel. This situation must be seen in historical terms, however, as part of an eternal alternation between long periods of slavery and all too brief moments of freedom. But today things are worse because now we are held by a "slavery of ideas." The cinema, television, radio, through their sensationalism, all bear part of the responsibility for this sorry state of

affairs. Instead of pandering to the worst in man, we must try to understand him and his world. Most of all, we must avoid the smiling, false optimism that leads us to alcohol, tranquilizers, and the psychiatrist to avoid every possible anxiety in the world.

Rossellini says, furthermore, that we must begin to reestablish the rapport among various nationalities that existed immediately after World War II, and the cinema has a significant role to play in this attempt, as does the newer medium of television. He speaks approvingly of his own television series on India, for "there I could not only show the image, but speak and explain certain things." At this point in his career, however, it is still the cinema that is paramount, and, in light of his later didactic films, for the somewhat surprising reason that it can be more emotional, finally, than the more factual material prepared for television: "Perhaps my television broadcasts will help people to understand my film. The film is less technical, less documentary, less explanatory, but because it tries to penetrate the country through the emotions rather than statistics, it allows us to penetrate it better. That's what I think is important and what I want to do in the future."[23]

Rossellini's concerns have not yet been broadened, or made more subtle, and they are obviously marked by their fifties' origin. Yet, here in embryo, we can detect the founding beliefs of the final fifteen years of his cinematic practice. In 1959, though, they were little more than beliefs. Ironically, Rossellini will next, for virtually the first time in his career, begin to make cinema the old-fashioned, conventional way—though not, certainly, what he had begun calling the cinema of "holdups and sex." His goal of freeing himself forever from the demands of the commercial cinema of sensation will finally be fulfilled, but only after five more years of struggle.