16—

Voyage to Italy

(1953)

In no country in the world is death so domestic and affable as it is there, between Vesuvius and the sea.

—Italian saying

Viaggio in Italia (Voyage to Italy), Rossellini's third film with Ingrid Bergman, is thought by many to be his finest, and, in fact, one of the greatest films ever made; thirty years after its premierc, it regularly makes the top-ten listing of Cahiers du cinéma . The film does not release its riches on a first viewing, however, and many knowledgeable film critics have been and continue to be reluctant to share the French enthusiasm for the film. Repeated screenings gradually begin to reveal its many subtleties and its links with Rossellini's previous films. Chief among the latter is the complex theme of marital conflict and its relation to environment, which was initiated in Stromboli . Rossellini has said: "I consider Viaggio to be very important in my work. It was a film which rested on something very subtle, the variations in a couple's relationship under the influence of a third person: the exterior world surrounding them."[1]

The film also may have been important to Rossellini as disguised autobiography. Pierre Leprohon has nicely described this aspect of the Bergman-Rossellini collaboration:

For the man whose mission is to express passion and human sentiments, the woman in his life becomes, quite literally, his interpreter. It is her look, her voice, her gestures, her appeal that allow him to express himself. It is as if he married her a second time, by imparting to her his dreams, thoughts, and aspirations, since she, receiving them, makes them her own and communicates them to others. There is every reason to think that Ingrid Bergman made, as Rossellini's interpreter, a great contribution to his work, not only by her acting, but by her presence, by her aura.[2]

This much is certainly true; Robin Wood, however, finds almost exact analogues between the situations of characters in these films and Bergman's personal life.

Thus, Stromboli depicts her as the displaced person, Europa '51 dramatizes her guilt over leaving her child, and Voyage to Italy , along with the final collaboration, Fear , concerns the breakdown of their marriage. While provocative, Wood's list finally seems too conjectural and, worse, too reductive, to be of any real use. Nevertheless, his description of the autobiographical dynamic in Voyage to Italy is suggestive. For him, Katherine Joyce is also Ingrid, the Swede in Italy, uncertain about her future: "The poignance of the sequences in question arises out of the fusion of the two, the projection of the tension and uncertainty they have in common. It is a fusion—closely connected with Rossellini's very personal but immensely influential blending of fiction and documentary—possible only in the cinema."[3] Wood's description of the tension in Voyage to Italy is clearly related to that interplay between realism and reality that we have been tracing in Rossellini's other films, especially to the ontological dynamic Anna Magnani enacts in Una voce umana .

Rossellini's original plan was to adapt Colette's novel Duo (1934), which concerns a "happily married" couple whose marriage falls apart because the husband insists on upholding traditional views of marriage rather than responding to the specific sexual and emotional needs of his wife. When the wife refuses to apologize or feel guilty for an old love affair that the husband has discovered, he begins to moralize obsessively, finally losing control and taking his own life. In its concentration on the dynamic shifts of power within a sexual relationship, the novel is obviously related to the film, and its choice by the director tends to lend credence to Wood's autobiographical thesis. The focus of the novel, however, is very intensely on the couple, with no attention paid to their environment, and it is here that the film most strikingly departs from Colette's fiction.

Looking for an international male star to play opposite Bergman, Rossellini settled on the superficially suave and controlled George Sanders who, since his death, has been revealed as the desperate and deeply unhappy man he always was. By the time Sanders arrived, however, Rossellini had discovered that the rights to Colette's novel had already been sold. To keep Sanders interested, he immediately set out to draft another screenplay, or rather, treatment, that was to retain some elements of Colette's novel. Rossellini was not in the habit of discussing his plans with his actors, however, and Bergman confessed in her autobiography, "I was quite bewildered too, but I thought Roberto is Roberto; he might do another magnificent Open City . After all, we're going to Naples and he'll be inspired there."[4] Like most Italian film critics, Bergman, too, was waiting for Rossellini to stop all the "foolishness" and return to the scene of his earlier successes. This passage and others from her autobiography suggest that Bergman, like the vast majority of contemporary Italian critics, was ignorant of what her husband was really up to and, in fact, suffered a great deal during the making of these films, sublimating her own strong sense of professionalism to her continuing conviction of Rossellini's genius. As the cowriter of her autobiography explains: "Even Ingrid began to have doubts after the first two weeks shooting which consisted of her staring at ancient statues in the Naples Museum while an equally ancient guide bumbled on about the glories of Greece and Rome."[5] The voice of Hollywood and its obsession with the new and young echoes clearly

in this obtuse description of one of the most thematically complicated and emotionally fraught scenes of the film.

Sanders, trained to have the same expectations of standard Hollywood operating procedures as Bergman, became increasingly upset over Rossellini's penchant for assuring a spontaneous performance by withholding dialogue until the day before shooting. Each night found him talking by telephone to his psychiatrist back in Hollywood, and Rossellini finally sent for Sanders' wife, Zsa-Zsa Gabor, to try to cheer him up. More than once he simply broke down in tears, unable to continue for the frustration. At one point during the shooting, Sanders decided to go public with his anxiety, telling Riccardo Redi, a writer for the Italian journal Cinema , that when he complained about the lack of a finished script, "Rossellini decreed that I was an impossible man. People talk about neorealism . . . it's a joke. The real reason that Rossellini films in the streets is that studio sets cost money. I've seen some misers before, but I've never met anyone who could equal him. . . . I've heard that the film will be called Vino nuovo , and that's a perfect title, for new wine is always bad."[6]

Finally, Rossellini put a fatherly arm around Sanders' shoulder and said, "What are you getting so depressed about, at the worst you'll have made one more bad film—nothing worse than that can happen. . . . We've all made good films and bad films. So we'll make another bad one."[7] Robin Wood has suggested, in his interview with Bergman, that "George Sanders does look terribly unhappy all the way through" and that "it's a rather serious blot on the film."[8] Viewed another way, however, Sanders' unhappiness and lack of ease can be said to put an edge on his interpretation of the character that actually works quite well within the context of the film's unconventional narrative technique. Nor was Rossellini himself unaware of this effect. In the Aprà and Ponzi interview, he implied that Sanders' problems were simply more grist for his mill: "To be frank . . . you have to make them work for you. . . . Don't you think he was obvious for the part? It was his bad moods rather than his own personality that suited the character in the film."[9]

Rossellini's refusal to do things in the Hollywood manner extended, as usual, to his storytelling as well, and Voyage to Italy represents the perfecting of unconventional narrative, affective, and thematic strategies already present in his work from the very first. Thus, all the film's dramatic moments are consistently undercut. Nor is there much plot to speak of—a marriage is breaking up under the strains of a trip to Italy, and we watch; little else happens. Apparently superficial detail, however—the smallest, most fleeting facial expression, for example—assumes enormous proportions, as it does in the work of Dreyer, Mizoguchi, and Bresson. Episodic rather than linear in its development, the film emphasizes rhythm, suggestion, and nuance. Longueurs and temps mort are left in the finished film, rather than being edited out through a snappy montage that presumably would have moved things along better. (But what things? The minimal plot? Here, the surface of life is its depths.) It is a film composed of elements as tiny as barely perceivable emotional textures, and as immense as the meaning of life and death.

The other names by which the film was known when originally released dis-

play its distributors' complete misunderstanding: The Divorcée of Naples, The Greatest Love, Love Is the Strongest . In England, of course, it is still known as The Lonely Woman , a title that stresses only one side of the film's emotional dynamics and, like the mistranslation of De Sica's plural Ladri di biciclette into the singular Bicycle Thief , denies the thematic point of the film. Initial critical reaction was also swift and predictable. G. C. Castello, writing in the influential Cinema , rose to new heights of righteous indignation in the campaign against the director: "By this time, we've given up on Rossellini. But what is beginning to get annoying is that he has managed not only to ruin himself, but he's also ruining the woman who would, not unworthily, have succeeded Greta Garbo one day."[10]

This same critic objects that the film does not give enough information, especially psychological information about the characters. He wants, he says, to know why their marriage is going bad. What Castello misses is that the film offers their situation as an existential given, purposely denying us a previous "psychological case history" (an essential component of the code of realism) that would reduce the characters' rich, impenetrable presence, so much like that of people we meet in everyday life. The brilliance of Voyage to Italy is precisely its refusal to specify a "why," for that would be to recuperate human complexity and ambiguity into the graspable, the knowable; an illegitimate domestication, like most films, of the troubling inconsistencies of life.

Fortunately, critical opinion has changed over the years. Even by 1965, when the Italian journal Filmcritica conducted a poll of twelve of its collaborators on "The Ten Best Italian Films From Ossessione to the Present," nine mentioned Voyage to Italy .[11] This is also the film that crystallized the support of the nascent French New Wave around Rossellini's work at a time when his fortunes with Italian critics were at their nadir. Of the early French responses to the film, perhaps that of Eric Rohmer, written in 1955, is the most provocative. For Rohmer, Rossellini is playing with our built-in, automatic film responses without actually trying to break them. He makes us look for some significance behind the characters' actions: "The ancient link between the sign and the idea is broken, and a new one arises which disconcerts us." According to the French critic, this aesthetic manifests itself in a wholly new style; Rohmer openly admits that his mind wandered at times during the screening, but insists this is unimportant. At this point, however, Rohmer moves from an almost protostructuralist position to his more characteristic religious essentialism: "In this film in which everything seems to be merely accessory, everything, even the wildest wanderings of our minds, is part of the essential." For Rohmer, the third character of the film, as in Murnau's Sunrise , is God. In this way, the critic is once again able to recuperate the fragmented and the aleatory as their inverse, that is, expressions of the wholeness and unity of being.[12]

In Voyage to Italy Rossellini's use of temps mort reaches a new level of complexity and suggestiveness, but develops clearly from the experiments undertaken in the uncut Italian version of Stromboli . In the much-remarked opening scene, for example, when we first see the Joyces driving along the highway toward Naples, the boredom is palpable. The car's engine hums soporifically, a train speeds in the opposite direction; immediately following the credits we have cut quickly

to a train whistle that suddenly rends the image. Jose Guarner has described this sequence well: "This rather long-held image of reality . . . give[s] a curious feeling of continuance, as if the film had begun a lot earlier. We are not present at the opening of a story, merely coming in on something that was already going on, as we do in real life. Viaggio in Italia is also a film about time and duration."[13]

Seven years after the film was first released, Pierre Marcabru wrote in Arts that in this film the characters exist for themselves, not for the cinema, and thus proclaim a new cinema of immobility: "In the immobile and the insignificant is the very power of life."[14] Similarly, Leprohon explains why this kind of film is preferable to

those which rivet us to our seats with suspense or the more elementary emotions. "Spectator involvement" is really a shoddy aim, and for its victim a second-rate satisfaction. The greatest literature sets up a resonance extending far beyond the immediate illusion that it creates; and the best films are those that have us accompany the characters as their friends rather than step into their shoes.[15]

Detail is built slowly, as when the couple is taken on a tour of the Neapolitan villa they have inherited from their uncle Homer. At first the time spent on the tour seems wasted. It is only later, as we shall see, when the stability and presence of the house are implicitly contrasted with the forever-moving automobile with which the Joyces surround themselves, that we realize the significance of this temps mort that almost any other director would have summarized with a series of quick cuts. It is also clear that Rossellini knew just what he was doing. In the interview with Pio Baldelli and his students in 1971, he referred obliquely to this sequence, linking it in an unexpected and not entirely clear way to his later films:

If I don't live in the context of things, of everything, I can't arrive at those key points. . . . I've moved into the didactic phase in a very . . . it was continually showing signs of itself, for finally it was a need of mine that I hadn't identified very well. But do you remember, for example, Viaggio in Italia? Well, I had to do that long walk inside the house, seeing things, which everybody scolded me for. . . . Now, if this weren't there, if this milieu weren't there, how would you get to everything else? You wouldn't. If she [mistakenly "he" in the interview] hadn't gone through all those rooms, she wouldn't have gotten to the museum; if she hadn't gone to the museum, she wouldn't have gotten to the discovery of the bodies, she wouldn't have gotten to . . . she can't get there, because she could only have gotten there in that way, by means of . . . the improbable" [ellipses in original].[16]

Little is explained in this film. For example, when Katherine goes out for her first drive alone in Naples, reactions to what she sees play across her face, but only occasionally, when it is thematically pertinent, does the director actually show us in a countershot what she is looking at. Again, he is breaking one of the cardinal rules of "good" filmmaking, but the effect is to enhance the sense of waiting and the ever-fluttering possibility of a sudden outbreak of the unexpected. In any case, her reaction is more important than what she reacts to. At

the same time, however, Rossellini's documentary interest, as in earlier films, is strong, and he also wants to show the "reality" of Naples itself. He knows, however, that this "reality" is not available except through the consciousness of the characters, who thus mimic the director's own mediation. Bazin has described this dynamic well, because it fits so neatly into a phenomenological paradigm of the intentionality of consciousness. For him, the reality of Naples, as presented in the film, is incomplete, yet whole at the same time: "It is a Naples as filtered through the consciousness of the heroine. If the landscape is bare and confined, it is because the consciousness of an ordinary bourgeoise itself suffers from great spiritual poverty. Nevertheless, the Naples of the film is not false. . . . It is rather a mental landscape at once as objective as a straight photograph and as subjective as pure personal consciousness."[17]

This play of the objective and the subjective also reappears at the level of character identification: As Leprohon has told us, we accompany the figures rather than "become" them, and, as in Stromboli , Rossellini refuses to allow us the luxury of facile moral judgments in favor of one character over another. Most critics have assumed that Katherine is the aggrieved party, the clear victim of Alex's callous devotion to work and making money, but this may be because what are considered typically "male" faults of cruelty and violence are expressed in more obviously obnoxious ways. Bergman's traditional association with "good-girl" parts may also be a factor here. Most important, of course, is the fact that the narrative unrolls, basically, from Katherine's point of view. Yet, somehow Rossellini successfully mounts a subtle balancing act in which now one has the moral and emotional power advantage, now the other. The closely related communication theme is also stated in a couple of obvious scenes of mutual miscomprehension, but it moves beyond Stromboli in that now words are used as weapons, or to prevent communication. As Leo Braudy has aptly put it: "Voyage in Italy contains some of the most abrasive scenes between a man and a woman that have ever been filmed. But it is an abrasion of boredoms, spawned by the inconsequential, space-filling dialogue that will be echoed in Antonioni's L'Avventura ."[18]

At the first party they attend, Katherine is jealous over the attention Alex is paying to some of their young female acquaintances. At a later party given by Uncle Homer's aristocratic friends, Alex resents the obvious good time Katherine seems to be having, surrounded by admiring Italian men. During an early dinner scene, they seem on the verge of achieving reconciliation, and a chance word, an ungenerously interpreted phrase, sets them going at one another again. (Alex has suggested, in what seems to be good faith, that they try to enjoy themselves on their vacation, but Katherine responds with a curt, "If we don't enjoy ourselves it will be your fault.") Near the very end of the film, our sympathies perhaps begin to move more strongly toward Katherine as she assaults Alex's coldness again and again, only to be rebuffed. (Though it is a testimony to the film's unconventional handling of emotional dynamics that some critics have taken it for granted that it is Katherine who is being most difficult by the end.) When they do finally have their problematic rapprochement during the epiphanic finale—which will be discussed later—Alex's fear that Katherine will "take advantage" of him if he says he loves her makes it clear, in retrospect, that

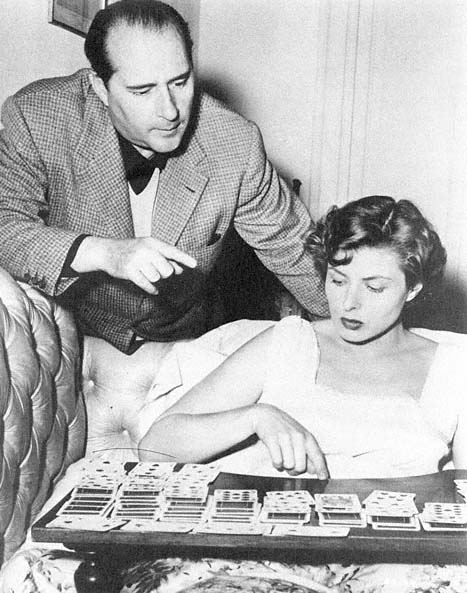

The director coaches his wife for the solitaire scene in Voyage to Italy (1953).

he has been resistant because he fears becoming vulnerable. In this case, we believe Katherine is sincere, for we can see her expression, but Alex has been refusing to look at her.

The most perfectly balanced sequence, however, a marvel of suggestion, occurs at Alex's return from Capri. Katherine has been waiting up for him, playing solitaire, hoping that he would return that evening. But when she hears his car pull up, she must immediately turn out the light and pretend to be asleep so that she will not in any way put herself at an emotional disadvantage. What follows is a subtle, but riveting, series of intercuts on her immobile face in the shadows as she registers and absorbs every sound he makes, her eyes darting everywhere. The petty noises—his gargling, for example—seem abnormally loud and penetrating, at least partly because they have been foregrounded by the nearly static visual track. An elaborate choreography follows of lights being turned on and off, as each fears giving an inch.[19]

Far more is at stake between Katherine and Alex, however, than their own emotional problems. For they also represent opposing sets of abstractions, neither of which we are meant to view favorably. (This, of course, is another reason why Rossellini does little or nothing to sketch in their past lives for us, or to define them in terms of personal idiosyncrasy.) Neither is a complete human being; they are parts of a whole, and thus the distortions of humanity decried by Nietzsche's Zarathustra. Alex clearly stands for a soulless materialism that, as we have seen in Europa '51 and other films, was for Rossellini the chief evil of postwar European society. Alex is constantly thinking of his business affairs and worrying about the time he is wasting while in Italy, a country he views as the epitome of laziness and lack of industry. Katherine, however, represents an equally untenable spiritualism that is reflected in her idealization of her romantic poet friend Charles Lewington. He served in the British army near Naples and had written her about the city. As Alex nastily points out to Katherine, her visit to Italy has become a kind of spiritual pilgrimage to reevoke Charles' presence in the locations he had written about. As the couple sits in the hot Neapolitan sun, she intones from Charles' poetry: "Temple of the spirit, no longer bodies, but ascetic images, compared to which mere thought seems flesh, heavy, dim." Alex, his jealousy aroused like that of Gabriel Conroy in James Joyce's story "The Dead," from which Rossellini has borrowed,[20] says that he learned from Lewington that a man's cough can tell you more than the way he speaks.

KATHERINE: What did Charles' cough tell you?

ALEX: That he was a fool.

KATHERINE (getting angry): He was not a fool! He was a poet!

ALEX: What's the difference?[21]

As the film progresses, we realize that Katherine, at least, is learning from her contact with the Italian environment that is so foreign to both of them. She gradually becomes less romantically caught up in her poet's otherworldliness, for the forceful realities of her Neapolitan experiences begin to call her to the world. After being exposed to those things that Charles had written about—especially the powerful rawness of the statuary in the Naples museum—she begins to realize that his aestheticism was a projection of his own personality rather than a de-

scription of Italy. She admits to Alex, "Poor Charles, he had a way all his own of seeing things." This progression on her part also serves to bring us closer to her (there is no equivalent learning by her husband), but her recognition and overcoming of an excessive, crippling spirituality is only part of the process.

It is more than hinted that Katherine's problems are also sexual in nature; the penchant for spiritualizing her relationship with Charles is an obvious function of her presumed frigidity. But if we can fault Rossellini for having recourse to this sexist stereotype, it must also be said that this subject is implied rather than overtly thematized. Thus, when Katherine goes to the museum early in the film, she is overwhelmed; her guide's homely, banal chatter only serves to counterpoint the raw violence of these startling nude marble figures. They serve the additional function of representing a presumably more healthy and innocent past civilization, as when Irene and the Communist Andrea visit the Campidoglio in Europa '51 , a motif that Godard borrowed in Contempt . (To point up his various borrowings, Godard has his characters at one point watch Voyage to Italy .) Her encounter with the statues is turned into a series of profound, almost physical, confrontations with them, and the obviously foregrounded movements of the camera—all fast crane shots that whirl as they move closer, worthy of the most choreographed moments in Ophüls—bring her into a forced proximity with the statues that is clearly threatening. As Michael Shedlin has correctly pointed out, most of the crane shots in the museum include Katherine and the statues in the same shot, as opposed to all the previous point-of-view shots that have kept her visually, and thus psychologically, dissociated from what she is seeing and experiencing.[22] Deeply moved by this encounter with the overtly physical, sexual presence of the past, she later confesses to Alex, "What struck me was the complete lack of modesty with which everything is expressed. There was absolutely no attempt—" At this point she is interrupted by a knock at the door, and the subject is never brought up again. Later, when she is touring the ancient site of the Cumaean Sybil, the old and presumably harmless guide demonstrates to her how marauders of the past would have tied up a "beautiful woman" like her. She huffs away, muttering, "All men are alike," and the bewildered reaction of the guide indicates that at least in Italian, male terms, her response was not appropriate. The last hint of the sexual theme comes at the end of the film when Katherine is trying to identify aloud the source of the animosity between her and Alex. She suggests that "perhaps the mistake in our marriage was not having a child," and Alex responds that she did not want one, and now he thinks that she was right, because it would only have made their impending divorce more painful.

If sexual frigidity is only suggested in the film, however, the Joyces' childlessness is more overtly linked with the poverty of their lives, but as symptom rather than cause. Superficial interpretations of the film have complained that because Katherine is constantly seeing pregnant women in her outings and because their friend Natalia is praying for a child, what Rossellini, in effect, is suggesting is that the couple's problems would be solved if only Katherine surrendered herself to her proper biological role (or fate). It is rather more complicated than that, finally, but to understand how, we have to probe more deeply into the dynamics of conflict in the film.

What rules Voyage to Italy is environment. Like Thomas Hardy's fictional Wessex, it becomes a powerful third character in the film, and its name is Italy. Most baldly stated, the film is about Katherine and Alex's confrontation with this otherness so utterly opposed to everything they know and understand. Where Alex is materialistic and superrational and Katherine is, initially, at any rate, overly aesthetic and otherworldly, Italy is sensual and earthbound. It might be argued, of course, that Rossellini is merely glorifying and idealizing his native land: if all those cold foreigners could only experience the warmth and carefree joy of Italy (and have lots of babies), their problems would be solved. What is important to understand, however, is the precise way in which a Mediterranean system of values is being touted over the coldness the northerners bring with them.

In many ways, the film could be included in the genre of "road films," given the massive, continual presence of their car (which I want to explore in more detail in a moment) and the theme of a hostile environment that makes one reassess one's most deeply held values and convictions. When on the road, you are vulnerable, and so are the Joyces. The undeniable presence of Italy, both physical and psychological, constantly forces itself into their consciousness, in spite of their desire to conduct their business as quickly as possible and escape back to England. They wrestle with their pasta, they do not know enough to take a siesta (and do not ask), they expect everyone to know English. After they eat, all the "garlic and onions" give Alex a thirst that he can not quench. He complains about the driving, about the rampant laziness; at the party given by Uncle Homer's aristocratic friends, the Joyces learn about "dolce far niente" (how sweet it is to do nothing), a concept totally alien to their Protestant souls. Uncle Homer, unlike the Joyces, was fully inserted into Italian life, and his friends miss him deeply. An even more important foil to the deadness and vicious advantage-seeking of the Joyces is the couple with whom they have most contact, Tony Burton (a fellow Englishman) and his Italian wife, Natalia. Here, North and South (which, as we saw in Stromboli , Rossellini always felt was the true division of the world, rather than East and West) are happily joined. Both husband and wife speak the other's language, and their relationship appears rewarding. They seem to embody that harmony of body, mind, and spirit that the film locates in classical civilization and continues to offer as a cure for present-day ills.

"Italy," the enemy, constantly intrudes upon the Joyces, in countless details, in nearly every frame. The Neapolitan singing that accompanies the opening credits is heard again and again, acting as the symbolic, but palpable, presence of Italy, occupying a sound track that constantly presses against a visual track concerned chiefly with the British couple. While they sit out on the roof of the villa drinking wine instead of taking a siesta like everyone else (with Katherine "shielding" herself from the Italian sun by wearing dark glasses), we see the symbolically suggestive Vesuvius volvano in deep focus in the background of the same shot.[23] Italy also intrudes in the form of sleep, about which much is made in the film. Both Katherine and Alex exclaim at different moments, "How well one sleeps here! Natalia tells Katherine at another moment that she should let Alex sleep because "sleep is always good for one." The laziness of Italy,

anathema to the businesslike Joyces, has begun insidiously to affect them as well.

Probably the most important symbolic motif that furthers this conflict between Italy and the Joyces is their car, so obviously and continuously present. With its prominently displayed British license plates, it represents that combination of mind-set and ideology known as England, which naturally they bring with them to Italy. It is where we initially see them, in this little bit of England pushing through a foreign land, and we understand seconds later that the very first shots we see have been taken through the car's windshield and side window, suggesting the inevitable construction of reality through one's own particular culture. The car comfortably envelops them and protects them, initially at least, from the influence of this strange country. Appropriately, it offers a cold and mechanical contrast to everything organic and living that we see throughout the film (in the very beginning, for example, they force their way through a lazy herd of sheep). Later, it sticks out blatantly among the ruins of Pompeii.

This thematic use of the automobile also explains, in retrospect, the earlier, lengthy tour of Uncle Homer's villa, for the villa functions as the symbolically static opposite of the Joyce's car, as an overt manifestation of Uncle Homer's organic participation in Italian life. Similarly, at various points throughout the film, a slow (often panning) establishing shot on the stolid villa, which begins a scene, reminds us subtly of its symbolic role, opposing the ceaseless, frenetic movement of the automobile. When Katherine makes her trips into Naples, she can only grumble about how selfish and unfeeling Alex is, for as long as she is in the car, she is enveloped in her own miserable, little existence and its multiple blind spots. But, like Alex and Katherine themselves, the automobile is not impervious to Italy's influence, and the environment continues to assault Katherine through the windshield. Yet it is only when she actually gets out of the car—at the "little Vesuvio," the museum, the Cumaean Sybil, at Pompeii, and at the end of the film—that she becomes truly affected by what she experiences. Similarly, when Alex improbably has the car after his return from Capri, he picks up a prostitute. Until this point, he has remained rather shielded, unlike Katherine, but when the woman invades his physical and psychological territory by entering the car, she brings with her the messiness of life in the tragic story she recounts.

But what exactly does this continual presence of Italy stand for? Clearly it is not to be taken as the fulfillment of some tourist-brochure writer's fantasies about sun and fun. It does, of course represent a greater openness to sensuality and emotion, and a greater connection with what we might call the fecundity of life, but it stands just as closely to death. Italy is seen in this film as a place where one is more consciously aware of life and death: because life is contingent, and death holds final sway, life itself, as Heidegger claimed, is enhanced in value and intensity by an awareness of death. What the Joyces need is not to have babies (or not only to have babies), but to be snapped out of the abstraction their lives have become, linked as they are only with the conventional, decentered signs of money and the other intangibles that modern life substitutes for directly lived experience. Thus, while it is true that in one of her drives through Naples, Katherine is overwhelmed by the number of babies and

pregnant women she sees, her first experience of the city stresses a funeral carriage and numerous black-edged announcements of local deaths. In Naples, as the epigraph to this chapter suggests, one is even closer to death than in the rest of Italy, and Rossellini delighted in telling interviewers, when discussing this film, how Neapolitan black marketeers spend the first big money they make one elaborately decorated coffins rather than on food and clothing. Natalia takes Katherine to visit the catacombs; the English woman is shaken by this place drenched with mortality and overflowing with skulls, and cannot understand why anyone would adopt a dead person to "take care of." Poor Alex cannot pick up a prostitute without her instantly beginning to tell him of a friend's recent suicide and her own temptations in that direction. In the interview with Aprà and Ponzi, Rossellini insisted:

[Katherine] is always quoting a so-called poet who describes Italy as a country of death—imagine, Italy a country of death! Death doesn't exist here, because—it's so much a living thing that they put garlands on the heads of dead men. There is a different meaning to things here. To them death has an archeological meaning, to us it is a living reality. It's a different kind of civilisation.[24]

The death theme reaches its dramatic climax—a "climax" that is characteristically understated—in the magnificent scene that takes place at Pompeii. Seconds after Katherine and Alex's most bitter argument, which has ended in a decision to get a divorce, their host Tony comes to collect them and insists that they go with him to the digs. The archaeologists have come upon a hollow in the ground, which usually indicates a place where people were caught and instantly killed in the great eruption of Vesuvius in A.D. 79. Their emotions rubbed raw, the Joyces beg off the visit, but Tony insists that it is the chance of a lifetime and that they must come with him. Unable to refuse, the distraught couple accompanies Tony to the site, where the workers are to pour fresh plaster of Paris down into the hollow through small holes they have drilled. As the rather bizarre musical theme picks up (a theme we have already heard during Katherine's other wanderings through history and the strange spots of Naples) and then modulates into a tense, tragic, bitter melody, dirt is scraped off the hardened plaster. One by one, body parts are revealed. The parts begin to form themselves into a man and a woman; death has caught them making love, or at least wrapped tightly in each other's arms. Suddenly, the museum, the catacombs, and the Cumaean Sybil all come together in one startling image: the physicality and rawness of the ancient world, the ubiquity of death in life, and love, however inadequate and flawed, as the only possible solution. At the sight, Katherine breaks down sobbing and rushes away, and Alex moves to help her. Rossellini offers no overt explanation for her reaction. Alex makes the standard excuses to the men on Katherine's behalf, and they prepare to leave. To get back to the protection of their car, they have to traverse what remains of the Roman town, and the effect on us is similar to what Katherine has experienced in the museum. In long shot, we see them move across the barren ruins, once full of life and now so full of death. The tragic musical theme intensifies, and

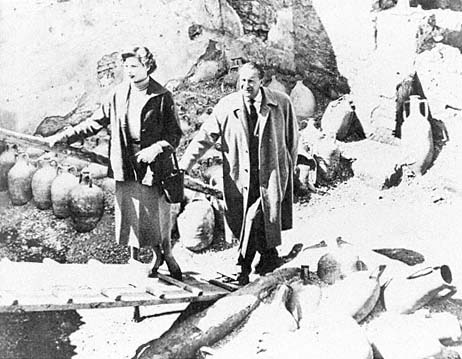

Love, death, and Italy: the Joyces (Bergman and George Sanders)

amid the ruins of Pompeii in Voyage to Italy .

the effect is truly moving. Finally, the emotional encounter seems to have had a positive effect on both of them. Alex ventures: "You know, I understand how you feel. I was pretty moved myself. But you must try to pull yourself together." Hopeful, she responds, "Oh, did it effect you the same way? . . . I've seen so many strange things today that I didn't have the time to tell you about. . . . There are many things I didn't tell you." She begins to apologize for their earlier argument, but Alex, perhaps assuming that she is only trying to trap him, rebuffs her: "Why? Our situation is quite clear. We've made our decision. You don't have to make any excuses." She hardens herself, and when Alex taunts her once again about her dead poet, she shouts, "Oh, stop it! Must you continue to harp on it? I'm sick and tired of your sarcasm. We've decided to get a divorce and that settles it!" They continue picking their way through the ruins, and suddenly the musical theme turns black. At this point, Katherine stops and utters the most convincing, devastating line of the entire film: "Life is so short!" The realization of death's ubiquity has completely overwhelmed her, given the "many strange things" she has been seeing all day, but there seems no way out of their endless bickering and advantage seeking. Alex replies ambiguously, "That's why one should make the most of it." The camera follows

them for a long time in an utterly desolate long shot, until they reach their car.

Immediately after, we hear the joyful bounce of parade music and cut to Katherine and Alex, once again safely ensconced in the automobile, as they fight their way out of Naples. This is the final scene, the most controversial of the film. As we initially located them moving toward the city in the car, we now see them moving away. The circle seems to be complete, and while the constant presence of Italy has forced them to confront the emptiness of their married life together, it has yet to effect any internal changes, at least that we can see. But one does not go through such intense emotional encounters and emerge unchanged. Subtle influences are working on them without their knowledge.

They have wandered into the middle of a huge religious process in honor of San Gennaro, from whom Neapolitans virtually demand a miracle each year during his festival, as Rossellini told Truffaut and Rohmer in 1954. Horns blow and confusion reigns as the couple picks over the remains of their marriage. Katherine, who has been more deeply affected, seems to seek a reconciliation, but Alex, suspicious, continues to reject her advances. When he says it is lucky they have no children because "it would make the divorce even more painful," she jumps on this: "Painful? Is it going to be painful for you?" "Well, more complicated" is his cold response. They continue to push their huge British car through the crowd (and the claustrophobic visual effect is enhanced by the complete avoidance of long shots), cold steel against human flesh and religious emotion, and ultimately they are forced to halt. The car is eaten up by the wave of humanity, by Italy, the way water rushes over a seemingly immovable obstacle and carries it away. Attention shifts to the parade, which we watch for a while, until Alex, still seemingly unaffected by his Italian experience, says: "How can they believe in that? They're like a bunch of children!" She replies softly: "Children are happy." Then she suddenly blurts out, "Alex, I don't want you to hate me. I don't want it to finish in this way." And Alex replies with lines that make his resistance more understandable and that again right the emotional balance between them: "Oh, Katherine, what are you driving at? What game are you trying to play? You've never understood me, you've never even tried. And now this nonsense. What is it you want? "Nothing," she spits out at him. "I despise you."

Then the significant moment: they decide to get out of their car, away from the protection of their lifeless culture. Instantly the crowd begins shouting, "Miracolo! Miracolo!" ; and though we cannot actually see anything—perhaps appropriate for a modern-day "miracle"—the immense crowd rushes forward, taking Katherine along with them. The shot is visually brilliant: the crowd moving powerfully ahead, away from us, Katherine pulled with them, fighting the emotional wave of the Italians, but turned back toward us and Alex, screaming wildly for help.[25] For once the sheer violent press of life forces them out of the sealed intellectual realm they have wanted to keep to, and into the swirling world of the emotions. Katherine needs Alex, suddenly, on a brute existential level that is apparently new to them. Alex rescues her, and the film cuts to a closer shot of them—the northern giants surrounded by the Neapolitan pygmies—as they clasp each other in their arms (like the Pompeian lovers):

KATHERINE: Oh, I don't want to lose you. (They embrace )

ALEX: Katherine, what's wrong with us? Why do we torture one another?

KATHERINE: When you say things that hurt me, I try to hurt you back, don't you see, but I can't any longer, because I love you.

ALEX: Perhaps we get hurt too easily.

KATHERINE: Tell me that you love me.

ALEX: Well, if I do, will you promise not to take advantage of me?

KATHERINE: Oh, yes, but I want to hear you say it.

ALEX: All right, I love you.

The camera at last pans away from them, resting a long time on the anonymous faces in the crowd, transfixed by the miracle they have just seen; it finally moves to an enigmatic one-shot of a single member of the band. As we, too, struggle to reconcile ourselves to the miracle we have just witnessed, the film ends.

The familiar Rossellini pattern is there: the sudden, cathartic, epiphanic moment of grace when all is righted (or in some films, where the point of tragedy is stated), a technique that goes back at least to Open City and the quick, ironic epiphanies of Paisan . The scene most closely resembles the "miraculous" ending of Stromboli , of course; there we saw the giving over of self to God through a primitive religious emotion, and here the giving of self to another person through the catalyst of the religious emotion of others. But if critics have been unconvinced by the ending of the earlier film, they have been even more vociferously disappointed by the ending of Voyage to Italy . What does it mean? Can we believe it? What has happened to alter the emotional pattern of years? Most critics have refused to accept the couple's reconciliation at face value and have seen it as either completely unconvincing or at best a momentary rapprochement that will shortly break down (Truffaut's view at the time). Rossellini himself had a complex opinion concerning the ending, which makes it seem even denser than that of Stromboli . He told Aprà and Ponzi:

What the finale shows is sudden, total isolation. . . . Unfortunately it's not as if every act of our lives is based on reason. I think everyone acts under the impulse of the emotions as much as under the impulse of intelligence. There's always an element of chance in life—this is just what gives life its beauty and fascination. There's no point in trying to theorise it all. It struck me that the only way a rapprochement could come about was through the couple finding themselves complete strangers to everyone else. You feel a terrible stranger in every way when you find yourself alone in a sea of people of a different height. It's as if you were naked. It's logical that someone who finds himself naked should try to cover himself up.

Q: So is it a false happy ending?

A: It is a very bitter film basically. The couple take refuge in each other in the same way as people cover themselves when they're seen naked, grabbing a towel, drawing closer to the person with them, and covering themselves any old how. This is the meaning the finale was meant to have.[26]

But this does not mean that their gesture is any less genuine for being instinctive; in fact, it seems more so, and it is significant that Rossellini does not explicitly agree that it is "a false happy ending." We might also say that the very unbelievability of the ending is itself thematic, as we saw with aspects of

Francesco , because it is not logical—that function of almighty reason that Rossellini, whose views changed drastically in the fifteen years between film and interview, now wants to credit above all. (Note that at this point he says that "unfortunately" not everything in life is based on reason.)

However one might want to read the ending, it was not the only thing in the film that displeased its initial reviewers, and like the other two major Bergman collaborations, it was a failure both critically and financially. The French, however, who, along with the Americans, had discovered Open City for Italian critics, were immediately more sensitive to its subtleties. The Eighth International Session of Film awarded it a prize as best film of the season; significantly, the judges were Jean cocteau, Abel Gance, and Jean Renoir. Also, the group of young cinephiles who had begun to form around the journal Cahiers du cinéma thought the film immensely powerful. For them, it perfectly embodied their desire for a personal style of filmmaking that was beginning to be known as la politique des auteurs . They also saw that its narrative and technical unconventionality pointed toward new possibilities beyond Hollywood.[27] Jean-Luc Godard, still five years from the making of his first feature, enthused:

In the history of cinema, there are five or six films that one wants to write about simply by saying "It's the most beautiful film ever made." Because there's no greater praise. Why should one speak any further of Taboo , of Viaggio in Italia , and of The Golden Coach? Like a starfish which opens and closes, these films can offer and hide the secret of a world of which they are at the same time the sole depository and the fascinating reflection.[28]

In the April 1955 issue of Cahiers du cinéma , Jacques Rivette said this of the film: "And there we are . . . cowering in the dark, holding our breath, our glance suspended on the screen which grants us such privileges: to spy on our neighbor with the most shocking indiscretion, to violate with impunity the physical intimacy of human beings, subjected without knowing it to our passionate watching; and, at the same time, the immediate rape of the soul.[29] Above all, these critics were struck by the film's novelty. In the same article, Rivette said, "It seems impossible to me to see Viaggio in Italia without experiencing, like a whip, the fact that this film opens a breech that the entire cinema must pass through under pain of death." Patrice Hovald expressed the phenomenological sense of direct, originary meaning most forcefully, calling it "the first film of a cinema which has not yet been created, because it seems like the first film which does not exist as a function of the others, but which, taking its own meaning from itself, thus finds its unique dignity."[30]

But even if one is unable to share the rhetoric of complete originality articulated by the film's early French supporters, it is still possible to see in it a remarkable shift in filmmaking practice. In its "free style," in Gianni Rondolino's words, one can glimpse the films of Antonioni and Godard and all the others that were to come in the sixties.

The mixture of genres, or the coexistence in a single work of narrative, dramatic, lyric, documentary, and essayistic elements, involves a kind of aesthetic "disharmony" . . . which opens the work beyond a more or less rigid structure. Then, this very placement of narrative and dramatic elements in the

finished structure of the film, with its frequent stylistic jumps, its unusual alternations, its formal carelessness, demands a lack of cohesion among its parts which favor the freedom of observation and the personal choice of the spectator. Finally and above all, the images and the dialogue are offered as "proposals" and not as "solutions."[31]

And in this new freedom of observation, it seems that Rossellini has finally fulfilled the hopes of André Bazin, not just on the level of the image or sequence, beyond which the French critic seemed unable to theorize, but on the more inclusive level of the film itself.