III—

THE BERGMAN ERA

12—

Stromboli

(1949)

At about the same time La macchina ammazzacattivi was being shot, Ingrid Bergman, then at the height of her popularity, wandered into a small "art house" in Los Angeles with her husband, Petter Lindstrom, to see the film that all serious film people had been talking about—Open City . The film was already three years old, but the effect was staggering. After the screening, Bergman turned to her husband and said: "Petter, we must get this director's name straight. If there is such a man who can put this on the screen, he must be an absolutely heavenly being!"[1]

It is revealing that even at the moment of this initial contact, Bergman should translate her emotional experience of the film into a fascination with its director. Later in her autobiography, in fact, she admits that "deep down I was in love with Roberto from the moment I saw Open City , for I could never get over the fact that he was always there in my thoughts. . . . Probably, subconsciously, he offered a way out from both my problems: my marriage and my life in Hollywood" (pp. 210–11).

A few months later Bergman saw Paisan alone, in an empty theater, and decided that if this wonderful director only had a "big name" actress to work with, "then maybe people would come and see his pictures." She wrote him the following letter:

Dear Mr. Rossellini:

I saw your films Open City and Paisan , and enjoyed them very much. If you need a Swedish actress who speaks English very well, who has not forgotten her German, who is not very understandable in French, and who, in Italian knows only "ti amo" I am ready to come and make a film with you (pp. 4–5).[2]

In his excited response, Rossellini outlined at great length the film that was to become Stromboli . It concerned an East European refugee who marries a poor, uneducated fisherman from the volcanic island of Stromboli (pronounced with the accent on the first syllable), off the coast of Sicily, in order to escape the refugee camp. It is clear from Rossellini's letter that Bergman had quickly become bound up with his entire idea of the film: "I tried to imagine the life of the Latvian girl, so tall, so fair, in this island of fire and ashes, amidst the fishermen, small and swarthy, amongst the women with the glowing eyes, pale and deformed by childbirth, with no means to communicate with these people" (pp. 8–9). Her husband "lives beside her and loves her with a kind of savage fury . . . just like an animal not knowing how to struggle for life and accepting placidly to live in the deepest misery." Once she realizes she is pregnant, the woman tries to escape the harsh, uncomprehending life of the island by climbing over the volcano. Rossellini's letter continues:

Frantic with despair, unable to withstand it any longer, she yet entertains an ultimate hope of a miracle that will save her—not realizing that a profound change is already operating within herself. Suddenly the woman understands the value of the eternal truth which rules human lives; she understands the mighty power of her who possesses nothing, this extraordinary strength which procures complete freedom. In reality she becomes another St. Francis. An intense feeling of joy springs out from her heart, an immense joy of living (p. 9).

What is perhaps most noteworthy in this treatment is Rossellini's obvious desire to represent women as real people with real difficulties and, like men, people who have to struggle with moral choices. As such, his project must have seemed enormously appealing to an actress who had probably reached her creative limit in Hollywood. As a popular magazine article of the time sympathetically, and correctly, suggested, she seemed to be looking for new challenges, and her two most recent pictures, Joan of Arc and Arch of Triumph had failed at the box office. It is also clear that she wanted to do something more serious than these Hollywood vehicles had ever allowed her to do. As for Rossellini, after staying for several weeks in early 1949 at the Lindstrom house in California, he was, according to Sergio Amidei,

in a strange state of tension because what he was really interested in was capturing Ingrid not so much to make a film, and certainly not to make money, but for love, because he was completely in love. . . . There was also a little vanity involved. You have to realize what Italy was like in 1948, and what Bergman and Hollywood represented. What Bergman represented to a good-looking young Roman guy![3]

Originally, the film was to have been bankrolled by Sam Goldwyn, who had been pestering Bergman for years to make a picture with him. She had suggested Rossellini, and Goldwyn at first reacted favorably. A press conference was called, and Goldwyn proceeded to tell the reporters what the picture was going to be like. Unfortunately, his description did not at all accord with Rossellini's idea of things; Goldwyn then decided that he had better see more of Rossellini's work and arranged a screening of Germany, Year Zero . When the lights came back on at the end, there was only an embarrassed silence; everyone had obvi-

ously hated it. A few days later, Goldwyn called Bergman to tell her he could not produce the picture after all because Rossellini did not know anything about budgets and schedules (pp. 197–98).

The next financing possibility was Howard Hughes, who had also been after Bergman for some time and, according to the actress, with more in mind than just making a film. One day he called to tell her that he had just bought RKO so that she could do a film with him, and so when she was casting about for financing for Stromboli , she thought of Hughes. Even though he was totally uninterested in Rossellini's idea for the film, he agreed, thinking only of Bergman's next picture, which she would make in Hollywood for him.

Ingrid had been joyously greeted on her arrival in Italy, a country that had become thoroughly sick of its American liberators. In the words of Liana Ferri, who served as Rossellini's initial interpreter with Bergman, the symbolic value of Rossellini's "victory" was enormous. "Every woman in Rome was in love, it seemed, with an American soldier. . . . Then he had captured Ingrid. This great actress was in Italy to make a picture and she was in love with our Roberto Rossellini! 'Bravo, Roberto, bravo!' She had left that cold Nordic husband of hers. Now she would find the true meaning of life and love" (p. 208).

Rossellini, Bergman, and the rest of the sixty-five people in the crew sailed off on the four-hour boat trip to the forbidding island on April 4, 1949. The male leads, Mario Vitale (the husband, Antonio) and Mario Sponza (the lighthouse keeper from whom Karin seeks help), were played by fishermen the director had found in Salerno on the drive down the coast with Bergman. The priest who tries to help her accept her new life was an old classmate of Rossellini's, who the studio, at odds with the director concerning his improvisatory methods, had sent to provide a script. The house chosen for Karin and Antonio was so decrepit that it had to be shored up with wood, but because there was no wood on the island, an old boat had to be taken apart to provide it. Because of the appalling heat and dust, Rossellini was forced to shoot scenes over and over, contrary to his normal practice. Bergman had to become her own hairdresser, and do without make-up (or indoor plumbing). Nor was there a double for the difficult sequences—for instance, when she had to walk on jagged rocks through the water. Even more grueling was the incredible final scene, in which Bergman had to climb up the side of the active volcano—her hands, feet, and eyes actually burning—while violently gasping for breath. Hardly the treatment a Hollywood actress was accustomed to, and Bergman's persistence attests to her professionalism and, of course, her devotion to Rossellini. The conditions were, in fact, so bad that one of the director's assistants was overcome by the volcano's fumes and suffered a fatal heart attack.

Probably most difficult for Bergman was Rossellini's relaxed method of making films, without benefit of a prewritten script. She was appalled by his habit of writing out lines of script for the next day's shooting on a matchbox. Nor had she ever worked with nonprofessionals before, and she was amazed by Rossellini's system of yanking string tied to their toes as a signal for when they were to come in with their bits of dialogue. "I didn't have a string on my toe, so I didn't know when I was supposed to speak. And this was realistic film-making! The dialogue was never ready, or there never was any dialogue. I thought I was going

crazy!" (p. 231). At times she simply blew up at Rossellini, totally frustrated. A great deal of expense was also incurred waiting for the right weather and for the volcano to cooperate in the filming of the scene that takes place at the edge of the crater. As to the actual eruption itself, Rossellini later told an interviewer that the volcano fortuitously started erupting one day while they were filming. "I always have confidence that these things will work out," he said.[4]

But all of these difficulties were smoothed over by the simple fact that Rossellini and Bergman had gloriously, if unwisely, fallen in love. The whole thing was messy from the first: paparazzi had followed them everywhere along their automobile trip down the Italian coast; a Life photographer caught them, in an unguarded moment in Amalfi, holding hands. At the end of March, Bergman wrote her husband telling him that she wanted to stay with Rossellini. The first official reaction to the brewing scandal came from Joseph I. Breen, head of the Production Code Administration. In a letter to Bergman, he mentioned the "expressions of profound shock" he had encountered everywhere regarding her apparent plans to abandon husband and daughter to take up with Rossellini, given that she was the "first lady of the screen." He also warned her that "such stories will not only not react favorably to your picture, but may very well destroy your career as a motion picture artist . They may result in the American public becoming so thoroughly enraged that your pictures will be ignored, and your box-office value ruined." He then urged her to issue a denial immediately to stamp out "these reports that constitute a major scandal and may well result in complete disaster personally " (pp. 235–36; emphasis in original). Walter Wanger, the producer of Saint Joan , which had just been released, sent her a nasty cable that concluded, "Do not fool yourself by thinking that what you are doing is of such courageous proportions or so artistic as to excuse what ordinary people believe" (p. 237).

Friends like Irene Selznick soon began offering support, however, and things became a little easier. Ernest Hemingway wrote, "If you love Roberto truly give him our love and tell him he better be a damned good boy for you or Mister Papa will kill him some morning when he has a morning free" (p. 241). But Ingrid continued to suffer guilt at leaving her family. The situation became even more difficult and melodramatic when Petter showed up in Sicily to "talk things over," and the possessive Rossellini threw a fit.

In the meantime, RKO was becoming increasingly preoccupied by the fact that the filming had gone over schedule by a month and, more importantly, over its $600,000 budget. Rossellini was given an ultimatum in the middle of July that if the picture was not completed in a week it would be abandoned. Bergman and Rossellini replied, detailing the tremendous hardships they had had to endure, and were given a short extension. Finally, in early August the shooting was finished.

Then trouble began in earnest. First, the world found out that Bergman was pregnant with Rossellini's child and the paparazzi began their twenty-four-hour stakeouts in the hopes of getting pictures. The baby, Robertino, was finally born on February 2, 1950, and to avoid the photographers, mother and child escaped from the hospital some days later in the middle of the night. Even the Congress of the United States became obsessed by the love affair. On March 15, 1950,

Senator Edwin C. Johnson of Colorado introduced a punitive bill in the Senate to license "actresses, producers and films by a division of the Department of Commerce." He assumed that the entire scandal had been manufactured to boost box-office receipts and denounced the "disgusting publicity campaign . . . the nauseating commercial opportunism . . . the vile and unspeakable Rossellini who sets an all-time low in shameless exploitation and disregard for good public morals" (p. 273). On the floor of the United States Senate, he complained: "When Rossellini the love pirate returned to Rome smirking over his conquest, it was not Mrs. Lindstrom's scalp which hung from the conquering hero's belt; it was her very soul. Now Mrs. Petter Lindstrom, and what is left of her has brought two children into the world—one has no mother; the other is illegitimate" (p. 274). Significantly, he added that Bergman had once been his own favorite actress, and suggested that now she must either be suffering from schizophrenia or was under hypnotic influence, since "her unnatural attitude toward her own little girl surely indicates a mental abnormality." He concluded that "under our law no alien guilty of turpitude can set foot on American soil again. Mrs. Petter Lindstrom had deliberately exiled herself from a country which was so good to her" (p. 274).

Problems with RKO continued to build. The original idea was to make two versions of the film—one Italian and one English—and the Italian version technically belonged to the "Berit Company," which had been set up by Bergman and Rossellini. The stock of this company was to have been held in escrow, as protection for RKO, but Rossellini never turned over the stock, and RKO became increasingly concerned about its million-dollar investment as shooting proceeded. Finally, RKO seized the negatives of both versions, but was unable to send them out of the country without Berit's authorization. At this point, Harold Lewis, RKO's production chief, hid the negatives in Rome; when Rossellini returned from Stromboli and discovered the seizure, he refused to turn over the negatives from the final week's shooting. The compromise that was finally reached was that Rossellini was to surrender the film and put Berit's stock in escrow, and RKO would return the negatives of the Italian version and allow him to edit it in Rome. The final Italian version would then be sent to Hollywood to serve as a guide for editing the English version.

What happened, however, was that RKO edited the English-language version exactly as the studio wanted to, and the result was so different from the director's original conception that he disowned it. Making things worse, the film's release in the United States was accompanied by lurid posters with which, according to Hollywood producer Dore Schary, Howard Hughes meant to capitalize on the scandal. Schary characterizes the poster's volcano "as a rather obvious phallic symbol"; Eric Johnston of the Motion Picture Producers Association even threatened Hughes with expulsion if he did not withdraw the posters immediately.[5]

The problem in properly evaluating this film is that the version seen in the United States—probably the only version that will ever be seen—is precisely the one disowned by Rossellini. Hence, most analyses have been skewed from the very beginning by not having the proper text to work with. The English version is actually some twenty minuts shorter than its Italian counterpart, presumably

in order to "streamline" the plot. I will therefore want to consider the longer version in some detail, so as to begin to set the record straight. Most important, however, is the fact that the ending was drastically changed by the studio, though it must be said immediately that even Rossellini's ending is problematic in its religious emphasis and will not be to every viewer's taste. Nevertheless, I think a case can be made for the rightness of this ending, at least in terms of the dynamic that the film itself establishes. No such case can be made for RKO's version, however, and the utter unbelievability of its ending has long kept viewers from a proper appreciation of the film.

The primary differences between the two versions in the beginning and middle of the film are clear-cut. In the beginning of the Italian version, the credits play out against a background of clouds, perhaps clouds of smoke from the volcano. In the English version, however, they run against a map of the Mediterranean, with the camera dollying ever closer to the island of Stromboli as the credits continue. The point of all this is to set the events geographically, a typical Rossellini maneuver, and thus one suspects that here, at least, his plans for the English version were being heeded. Even more important than the map, however, is the footage of island life that immediately follows the credits. In the Italian version, the action begins in the refugee camp; in the English version, however, a crisp voice-over (the principal difference between the two versions) outlines the island's physical characteristics, how the people earn their living, and their ongoing, complicated relationship with that representative of death in their midst, the volcano. Only then does the voice-over of the English version move us to the displaced-person's camp, once the island's documentary reality has been set. Thus, the beginning, at least, of the version Rossellini felt compelled to disown is very close in spirit to his own practice.

The next great disparity is that many of the details of Karin's troublesome adaptation to island life are cut in RKO's version. For one thing, all the "useless" transition scenes are removed, such as the couple leaving the camp, catching the train, sailing on the big boat, transferring to the small boat, and so on. What remains, however, is melodramatically heightened. The young lighthouse keeper to whom Karin will later appeal, for example, is on the same boat, but in Rossellini's version, his possible importance to later events is only visually hinted at by a simple insert of him sitting on the floor of the boat. In the English version, however, the threat he represents is made clear by a strong dose of theme music. This version also rhetorically cuts to a much closer shot of the volcano's seething crater when they first arrive—a shot that is visually and narratively unmotivated—while the volcano's fearsomeness is further underlined by its rumbling on the sound track.

The most important changes, however (excluding the changes in the film's ending, which will be discussed later), come after the couple have had a violent quarrel. Karin has accused Antonio of not understanding that they are from different classes, telling him coldly that he will need much more money to take care of a woman like her. At the close of her outburst, she begins crying. In the English version, surprisingly, much of her crying is retained, far beyond the usual limits for such a scene. In Rossellini's version, however, the crying goes on even longer, and leads imperceptibly to several other narratively unfocused

scenes that establish the creative temps mort we last saw in the finale of Germany, Year Zero , and that hearken back to similar moments in Rossellini's pre–Open City trilogy. Here, the crying scene is dragged out so long that Karin seems to go through several different stages of grief, filling us with tension because the rules of conventional filmmaking are deliberately being flouted. She hears a baby crying, puts money in a purse, hides the purse, and, still whimpering, goes outside, where the sequence finally ends. It is here, in fact, that Rossellini's long-take technique, characteristic of nearly all his subsequent films, assumes its definitive shape.

The sequences that immediately follow have also been removed from the English version, presumably because nothing "happens" in them and the narrative is not overtly advanced. First, we are shown an extreme long shot from a completely vertical bird's-eye view, looking down on the town, which turns its poor houses and narrow alleyways into a highly stylized maze. Karin runs around frantically, like the laboratory mice in the later Fear , shouting, "I want to get out!" The film then cuts to other, similar vertical shots that continue the maze pattern for quite some time, nicely spatializing Karin's mental and physical situation. Meanwhile, the baby is still crying and Karin continues her search for this other form of human life on the island. She then finds a small boy and tries to speak to him in English and pidgin Italian: "Say something to me!" she begs him. "Talk! Talk!" (Again, the Rossellinian urge for communication.) Frustrated at his refusal, she walks disconsolately past bare trees, harsh rocks, and various cacti that serve as a Waste Land —like index to the islanders' spirit and her own increasing desperation, a motif that looks forward, again, to the films of Antonioni. Most importantly—and most technically daring for 1949—she leans over the rocks, the cactus behind her, and begins chewing a piece of grass and stroking her cheeks with it in what becomes an extremely long take. Karin's ability to find pleasure on this godforsaken island, we realize, is reduced to the simple sensuality of a blade of grass on her face. The very length of the shot, and its "purposelessness," has allowed us to know her in a way utterly different from the more obvious techniques of conventional film narrative.

When this part of the scene is over, the camera follows Karin back to her pitiful house, and there we find some old men who have begun fixing things up on her husband's orders. She begins talking to them, and it turns out that they have all returned from America because they are old and they want to be buried on the island when they die. One of them, the most ancient, adds a nice comic touch when he says that he is going back to Brooklyn in about ten years. This scene is also significant because it continues the theme of the desperate emigration long associated with the island, which finally becomes an obsession with Karin. Even more importantly, perhaps, the old men cheer her up. We realize that Karin, like people in real life, may shift moods drastically, even if this shifting appears "inconsistent" in classic realistic acting and narrative terms. Again, none of the scenes described above remains in the RKO version of the film.

Apart from the differences, though, the two versions obviously share a great deal of common ground, and it is on this that we should focus. For the most part, the film works in terms of paired oppositions, the principal being, of

course, that of Karin, the tall, fair, cold, somewhat awkward northerner, and Antonio, the short, swarthy, warm-blooded southerner, at home in his environment. Rossellini was fond of saying that the real division in the world was not between East and West, but between North and South, and this theme will reappear in the later Bergman films, most notably and most richly in Voyage to Italy . Here the contrast is always visually before us, given the physical characteristics of these two actors; Vitale, in fact, seems to have been chosen for the part precisely because his physiognomy contrasts so sharply with Bergman's.

Karin and Antonio's differences are stated immediately, accompanied by an overt use of symbols. Thus, when we first see them together in the camp, they are kept apart by barbed wire, which serves to suggest both the psychological and emotional separation that will continue to plague them, as well as the pain and violence they will inflict on each other. When they laughingly try to talk—in another appearance of Rossellini's obsessive language theme—they can barely make themselves understood, and in frustration Karin at one point says, "I don't understand!" He wants to marry her, he says, a proposition Karin welcomes as a way of escaping the hated camp. She says to him, "What if I'm different?" thus putting into play one of the film's key terms. Antonio responds by saying, "I know women and if you're different, I'll . . . " meanwhile laughing and making a hitting gesture that prefigures the sexual violence to come.

Some critics have felt that one of the flaws of the film is Bergman's "excessive prominence," to quote Pierre Leprohon. A variant of this theme—still the orthodox Hollywood version of the Rossellini-Bergman collaboration—is that Rossellini ruined both of their careers because he did not know how to use her properly. It is just as easy to claim, however, that Rossellini knew exactly what he was doing, for he clearly means to play her in counterpoint against type. As Karin, Bergman is complexly amoral, and the ambivalence of this role proved to be one more insuperable difficulty for those already outraged by the difference between her on-screen Hollywood roles (Joan of Arc and the nun in The Bells of St. Mary's , for example) and her "scandalous" real life as Rossellini's lover.

From the very beginning, Bergman smashes stereotypes; cold and calculating, Karin first does everything possible to get a visa to go to Argentina. The cutting itself nicely suggests causality, for after she tells her fellow "inmates" of her obsession with getting out of the camp, the film cuts to the scene of the hearing of the visa board. When her application is denied, we cut to her wedding, implying that this legal ceremony is merely an alternate version of the one that failed. Karin is distracted during the wedding mass and could not care less. Not coincidentally, one of the very first people she meets on her arrival on the island is the local priest, and it is here that many of the film's oppositions are first articulated. He tells her that she will be happy here, this is her home now. She must, in short, give up whatever individuality she retains to live by the group's rules. We sympathize with her plight, but her expedient view of the wedding, and the priest's kindly and warm manner, contrasting with her rather uncivil responses, make us feel that she is not being fair, that she has not given the island and its inhabitants a chance. And thus is initiated one of the most

complex and important dynamics in the whole film. What makes Stromboli unique is precisely this refusal to completely favor either Karin or Antonio in their struggle, but rather to continue to insist, contrary to Celestino's view in La macchina ammazzacattivi and most conventional cinema practice, on the complexity, the mass of grays, that mark all human relationships, and that must also mark our moral judgments of others, including characters in a film. This refusal to take sides is the source of Rossellini's famous "distance" in the Bergman-era films, but it must be remembered that the distancing results primarily from the deliberate alternating of audience emotional response, rather than any supposed "coldness" on the director's part. This emotional alternation will be a major feature in the other Bergman films as well, and it is this that gives them their power. In fact, one of the major weaknesses of Fear , their last collaboration, is the breakdown of this dynamic, for in that film, despite Rossellini's apparent intentions, almost all the audience's sympathy is vested in the female character.

Karin asks Antonio why he kissed the priest's hand, and his response seems utterly foreign to this deracinated woman, this prime specimen of the spiritual decay of the postwar European world: "It's the custom," he says simply. They come to the broken-down shack in which he means to establish their family and he tells her grandly, "This is our home." Plunging forward, as always, he manifests his comfortableness and full insertion in this environment (cheerfully breaking down the door on the way), and in the process allows the camera to isolate her and reveal her increasing anxiety. Inside the crumbling house, Karin is further isolated against its grays and blacks, her apprehension in counterpoint to Antonio's obvious happiness. The scene then dissolves to a shot of him walking behind her toward the sea, the site of her outer limitation (and also the obvious place of escape that is denied her), and the impression we have of him is as a hulking ape. He speaks hopefully of the land on the island on which crops can be grown, and when he cannot remember the English word, he picks up a handful to show her. (Throughout the scene, his feet are symbolically bare, in contact with the land, while hers remain shod.) Just as he embraces her and says, "I'm so happy," the music builds to a climax and she violently pushes him away. She screams that she wants to go far away from the island, and Antonio reverts to the only set of values that he knows. "This is my home and you are my wife," he says firmly. "You stay here because I want to." For him, of course, words like wife and home have fixed, uncomplicated meanings.

Our own emotional position at this point is unclear. On the one hand, Antonio is clearly falling back on a model of male supremacy that we find unpalatable (and probably would have in 1949 as well). But we also appreciate his genuine love for Karin and for the earth, natural things, and his homeland. She, on the other hand, though clearly put upon, is absolutely uncompromising in her haughty demands. Rossellini will hold us in this complex emotional limbo throughout the film.

His purposeful ambivalence toward these characters was apparently there from the beginning. Regarding Antonio, he told Bergman in the long letter in which he initially outlined the story of the film:

I am quite sure you will find many parts of the story quite rugged, and that your personality will be hurt and offended by some reactions of the personage. You mustn't think that I approve of the behavior of HIM. I deplore the wild and brutal jealousy of the islander, I consider it a remainder of an elementary and old-fashioned mentality. I describe it because it is part of the ambience, like the prickly pears, the pines and the goats (p. 196).

So far so good. But then Rossellini betrays an admiration at another level for Antonio, and its Wuthering Heights brand of romanticism does not obscure a strong whiff of sadism: "But I can't deny in the deepness of my soul there is a secret envy for those who can love so passionately, so wildly, as to forget any tenderness, any pity for their beloved ones. They are guided only by a deep desire of possession of the body and soul of the woman they love. Civilization has smoothed the strength of feelings" (p. 196).

A split second after Antonio's assertion of the male prerogative, we understand the wide, unbridgeable emotional gap that separates them. The camera, echoing their feelings, cuts quickly to an extreme long shot that pins them in their forlorn isolation against the harshness of rock and sea. Karin walks away, leaving Antonio standing there. The camera begins suddenly to move in the opposite direction, panning up the hill past the pitiful town to the top of the volcano, that theophallic symbol of the ordering power of authority. This shot is followed by a cut to the bubbling crater, an obvious analogue to their own upset feelings, and then to their bedroom, where they sleep in different beds. In a short and wordless scene of great subtlety, we sense that Karin, who lies awake, is wrestling with ambivalent feelings. But she does not go to Antonio.

Our emotional division regarding the characters continues through the following scenes. Karin seems selfish and unfeeling when she tells Antonio that he is not good enough for her, that he will need much more money to keep a woman like her. In insisting that she is not an animal, she implies that he is, and an important motif is begun. Another scene casts Karin's fragile flesh against the forbidding backdrop of craggy rocks, and when she cries out to the priest that "this island drives me mad," and that she desperately wants to leave "the black rocks, the desolation, the terror," the emotional balance shifts once again in her favor. The priest, like Antonio, is hardly equipped to deal with a sophisticated women like Karin, and, falling back on his training, counsels patience while they save enough money to leave. But in the meantime, he tells her, she should make a "good home for her husband." And, in some easily missed lines, a new motif is articulated that is meant to prepare the way for, and make more believable, Karin's recognition of God at the end of the film. The priest says, "God will be merciful." She replies at the very last moment of the scene, "With me, God has never been merciful."

The next scene is principally documentary in tone, as we learn how the men make their livelihood fishing. Antonio is successful and returns with a pocketful of money and, developing the animal motif, a large fish for dinner. On one level, which will be elaborated later, the fish reminds us of Karin's status as victim. At another level it seems to be an alienating presence in the middle of the table, a challenge, and as such it signals the intrusion of nature, of the basic facts of life and death—Antonio's realm—into Karin's attempts to order her existence. It is

this very dichotomy that will be so brilliantly worked out in Voyage to Italy . Here, an extraordinarily long take, like the earlier one of her crying, focuses almost clinically on Karin's reactions to the fish's presence.

Momentarily reconciled to her situation, she decides to decorate the house. In the process, however, she inadvertently activates the second phase of her difficulties, for the local women strongly disapprove. (In the Italian version, which includes more details of this scene, she paints a Matisse-like fresco on the wall, has a man cut off the legs of the chairs to make them low, and brings in a cactus.) Worst of all, she removes Antonio's pictures of his family and his favorite saints. His aunt tells her she is not "modest." This clash with local customs continues when she goes to the home of a "bad woman" (who happens to own a sewing machine) to have a skirt altered. She and the woman joke harmlessly with some of the local rowdies who have gathered below the window, and Antonio, returning from his day's work, happily joins the fun. When he discovers to his embarrassment who is behind the curtain, he yanks Karin out of the house and in the process has to undergo a painful-to-watch male showdown ritual in order to pass. Later in the film, Karin, in a provocative outfit, is sunning herself in a scene that recalls the sunbathing American beauty of La macchina ammazzacattivi . She plays innocently with the children among the rocks, but we are also conscious that she is showing quite a bit of leg. The lighthouse guard, who we first glimpsed on the boat crossing to the island, and who Karin had discovered in the "bad woman's" house recovering from malaria, rows up at this point and shows her how to catch an octopus using a barrel. She falls in the water, he helps her up—her clothes clinging to her body—and they exchange a subtle, but meaningful, look. Then a sudden, chilling cut reveals a long line of black-clad women watching the whole performance with great relish from above. (In the English version, the powerful reticence of this scene is vitiated by the reductive voice-over that tells us how tongues will wag over this "simple, thoughtless act.") What follows is a brilliant sequence of Antonio on his way home: bawdy songs and imprecations calling him cornuto (cuckold) echo from quickly-closed windows along his way. When he finally reaches home, he fulfills the promise of violence we have expected from him all along and, without a single word, beats Karin savagely. The next morning, all of the old family and religious pictures have been returned to their original locations.

The struggle between the man and the woman is intimately tied up with the larger question, What is the proper balance between the needs of the individual self, especially one who is "different," and the needs of the group, as embodied in their life-regulating social customs? Part of the excellence of the film is its refusal to come down on one side or the other of this difficult question, like its refusal to make us identify exclusively with either Karin or Antonio. As Robin Wood has pointed out, in spite of the fact that almost everything we see is from Karin's point of view, "our sense of the alien-ness of the primitive community seen through Karin's eyes is everywhere counterpointed by our sense of the integrity of Stromboli's culture and its functional involvement with nature, against Karin's sophisticated needs and moral confusion."[6] Some critics have, for their own reasons, not wanted to credit this rich ambivalence, but have preferred to attack Rossellini for portraying Karin as unambiguously at fault. The

editors of the British Film Institute dossier on Rossellini, for example, insist that "the logic of the film itself leaves little doubt that Karin is the 'trouble,' not the priest-ridden village where wife-beating appears to be part of the 'simple' life close to the 'authentic' values of human existence."[7] Borde and Bouissy, earlier anti-Rossellini polemicists, lump together all the Bergman-era films and egregiously maintain that they are all about "the redemption of the unworthy woman," all concerned with effacing "the sin of having a wet and hairy sexual organ." They move quickly to a global indictment:

In summary, Rossellini specializes in an antiwoman cinema, or more exactly, the film of the familial settling of accounts. It's the old reactionary theme: ever since Eve listened to the serpent, she's been an idiot or a whore. The married man has a double function as redeemer. In accomplishing his conjugal duty, he transforms her into a mother. In torturing her for a good cause, he transforms her into a moral being.[8]

Sex is complexly present in Stromboli , but it is rarely expressed in any of the conventional ways. Indeed, Karin is a sexual creature who openly uses her sexuality to gain advantage in an unequal struggle. Yet Rossellini refuses to essentialize—at least in this instance, on the subject of woman—taking instead an individual woman's problems seriously and making them the focus of his cinematic effort. His essentializing move is rather to make her stand for suffering humanity.

The first important "sexual" scene is Karin's private meeting with the priest, at his home, which occurs the day after Antonio has discovered her in the "bad woman's" house. She goes to the priest in desperation, searching for someone who will understand her. She tells him that she is unhappy and thinks she's going mad, but the priest says that Antonio is unhappy too. (Her inner turmoil is visually signaled by the fact that, under her black sweater, she is wearing a dress with a bizarre, jagged-edge pattern.) She begs the priest for money that has been entrusted to him by emigrants for upkeep of the cemetery, making a convincing case in favor of supporting life rather than death—but we quickly realize that she is only thinking about herself and does not care in the slightest about the island's traditions. During her confession, she moves closer and closer to the priest, consciously or unconsciously, and tells him, "You are the only man here who can understand me." The point, of course, is that he is not a "man," but a priest, with a clearly circumscribed spiritual role to play, and it is this that she does not understand. As Karin gets closer, his discomfort increases. He denies that he is the only one who can comfort her. She moves even closer, and when his housekeeper enters with a liqueur, they guiltily jump apart. Throughout this part of their encounter, the shots are very tight (mostly over-the-shoulder), the kind of shots often associated with love scenes. After twice resisting Karin's continuing advances, the priest finally tells her that he can talk to her only in confession, and that she must leave. We cut to a one-shot as her pleading face is suddenly flushed with hatred. She screams that he is "just like all the rest."

This must have been a rather raw scene in 1949, but there is more than just a sexual drama going on here. One of the main problems causing most spectators to see the religiousness of the film's ending as unprepared for and un-

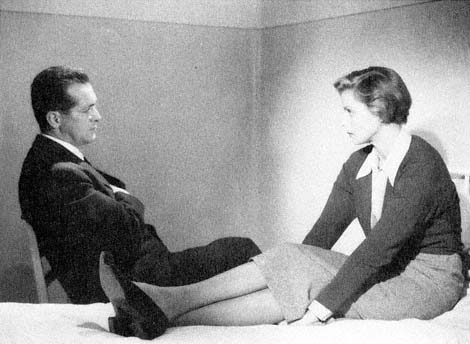

Victims: Karin (Ingrid Bergman) tries to protect a rabbit from

her husband (Mario Vitale) in Stromboli (1949).

motivated is that it is easy to take the priest in this scene, as Karin does, as just another person she is talking to about her problems, rather than as the representative of God that he and his villagers take him to be. In the film's terms, in other words, he is a spiritual figure who is trying to lead her to a more unselfish life, one that has a place for God. Thus, during their encounter she overtly puts matters in moral terms when she tells him, "I've sinned, I've been lost. I've chased illusions, adventures, as though an evil force were behind me." Confessing that she was a collaborator during the war, dating Nazi officers, she says, "I realize now how wrong I've been. I want to make something of my life. But this is too much—I can't go from one extreme to another." Finally, when the priest rejects her entreaties, she shouts, "Your God won't help!" The very power of this scene's sexuality, in other words, can cause the spectator to miss the spiritual drama unfolding at the same time.

Another important moment follows, a moment extending the animal-sexual motif that will reach its peak in the famous tuna-fishing sequence. Karin has come off badly in the scene with the priest, in spite of our initial sympathy with her plight, but again Rossellini turns the emotional tables. She finds Antonio in front of their home on her return from the priest, and he shows her an animal she has never seen before. She asks what kind of an animal it is, and is told that it is a ferret for hunting and killing rabbits. He proceeds to give her a gruesome display of how quickly and violently the ferret is able to dispatch the rabbit he

releases. All of Karin's frustration built up during the scene with the priest now pours out as she pounds Antonio wildly and calls him a "stupid, savage beast," but he only laughs at her inability to do any physical or psychological damage to him. The real source of her frustration, however, is that she sees herself as an animal, the defenseless rabbit being attacked. In the Italian version, Rossellini makes the point even more strongly as we cut back to the animals' death struggle; in a series of horrifying shots, including some close-ups, the ferret destroys the still wildly kicking rabbit and drags it away.

What follows is the interlude with the lighthouse keeper, mentioned earlier, the gossip of cuckoldry, and Antonio's savage beating of Karen to reclaim her as his property. He takes her on a "public relations" tour of the village—to the cemetery, to the church—where, with all the eyes of the villagers on them, he publicly reasserts his mastery over her. Her defeated, distracted presence in the church, far from any real religious devotion, suggests again, as we saw in several earlier films, the basic inability of organized religion to fulfill spiritual needs.

In spite of—or because of—her humiliation, this brutal treatment seems to have the desired effect, and a rapprochement of sorts begins to develop, leading to another emotional climax in the magnificent tuna-fishing sequence that was incorrectly identified by Claude Mauriac in his influential L'Amour du cinéma (to Rossellini's anger) as having been filmed by another director. In the very beginning of the sequence, Karin inappropriately has herself rowed out to the scene of the tuna fishing, again asserting her difference, for no village woman would ever think of intruding onto this male territory. With some of the very few pleasant words she ever says to Antonio in the entire course of the film, she tells him, "I want to be with you. I'll go if you want; I don't want to embarrass you in front of the other men." The coarse and simple Antonio, in love but clearly in over his head with this sophisticated woman, affectionately tells her it is all right for her to stay: (The warmth of this moment, of course, is greatly vitiated by the knowledge that it presumably results from her beating.)

The pace quickens as the nets are brought in closer and closer, and the sea begins to churn as the still-unseen fish try desperately to escape. The voice-over of the English version casts the scene in an overtly documentary mode, linking the annual reappearance of the tuna in the same place with the workings of a "higher power." The entire sequence is a brilliant textbook illustration, reminiscent of the Po episode of Paisan , of how to build emotion through rhythm, expectation, and suspended fulfillment. But the abstract beauty quickly turns into the more concrete reality of killing as the huge fish are speared one after the other and heaved inside the boat. As the violence mounts, the intercuts of Karen's shocked reaction come more quickly, resulting in an even more profound version of the revulsion she experienced in the scene with the ferret and rabbit. Again, however, she is not horrified just by the violence, but also because she sees an analogue of her own situation in that of the tuna. Were she merely reacting to the violence, we might be justified in considering her hopelessly alienated from the "true," "natural," life of the village. Instead, we understand that, like the tuna, she is a helpless victim whose selfhood is being extinguished by forces beyond her control. There is also an obvious sexual subtext operating in this sequence, and, as with the ferret scene, one that is clearly sadistic. Jean-

Claude Bonnet has suggestively described one of these elements: "The stranger who faints at the sight of enormous harpooned and bloody fish is sprinkled by the rough slap of a tuna's tail. 'It was horrible,' she cries in the next scene during the eruption, when we find out that she is pregnant."[9] The question that remains open, as usual, is where is Rossellini in all of this? Is he sympathizing with woman as social and sexual victim, or heaping more pain on her, trying to "redeem" her?

After the violence—sexual and otherwise—of the "day of the slaughter of the tuna fish," as the voice-over identifies it, we move to the obviously phallic expression of the volcano in its fullest moment of violence. From a shot of the volcano, we cut to a shot of Karin trying to light a fire in her oven, and almost as though she has begun some natural chain of events with her innocent act, the volcano begins to grumble in its loud bass voice. Again, the rhythm of the editing is perfect, and the beautifully composed shots move quickly before our eyes. United in the face of the overwhelming danger of an infinitely more powerful and more basic nature, Karin and the villagers momentarily put aside their superficial struggle as everyone moves out to sea on the fishing boats in order to escape the volcano's fury. The people in the water now become a kind of floating village, and we realize again that the village is indeed its people, not the houses or the earth on which they stand. They have taken their spiritual values with them, and gain solace in the monotonous repetition of the Catholic litany of the saints, offered as an incantation to propitiate the pagan god of the volcano. We learn that Karin is pregnant, and in the peace of the scene we think that a longer-range truce might be possible through the intermediary of the child, who will be both hers and the village's, in a way, a living merger of the self and the group. Significantly, she is no longer seen in isolated one-shots, but is now part of the larger whole. Her "different" culture, however, keeps her from joining in the recitation of the litany.

And, indeed, such a truce is not to be. The conditions of her existence on the island are simply not bearable; whether this is her fault or not is finally beside the point. Rossellini means to describe an existential condition rather than assign blame: this is simply the way things are, and now that a child is coming, her situation becomes all the more urgent. When she decides to leave the island, and will not be turned from her resolve, Antonio literalizes the film's continuing animal imagery by boarding up the doors and windows of the house, turning her into a caged beast. Once again, she must use her "feminine wiles" to escape her husband's ignorant brutality, and, like so many women before her, she is forced to turn to another man for her liberation, considering the physical threat against her. She plays up to the lighthouse keeper, luring him into a cave on the beach; this is obviously her place, the place of Circe and Calypso, of the vagina and the womb (It's peaceful here," she says), as opposed to the masculine power and patriarchal authority that reign everywhere else on the island and are embodied in the volcano. She tells him in blatantly manipulative tones, which make it difficult for us to side with her in spite of the pain she has suffered, that her husband "beat her like a beast." We also realize, however, that she must be manipulative, as this is the only weapon that remains to her. Refusing to wait a minute longer, she decides to escape by ascending the

forbidding volcano, a gesture laden with symbolic import. For Rossellini, as we have seen, the volcano represents the awesome power of nature that must somehow be engaged and submitted to in order to behold the power, majesty, and beauty of God. It is equally possible, of course, to see the volcano as the very embodiment of the patriarchal order of things, which Karen challenges, an order that must break the spirit of the independent, threatening female to its will.

As Karin ascends the volcano, she symbolically loses, one by one, all of her ephemeral appurtenances—her suitcase, her purse, and the money she has taken from Antonio to finance her escape. Powerful in the world of men, this money is worthless in the more basic world of nature. Smoke from the volcano billows around her, suggesting the fires of hell or purgatory, intimating that, from the director's perspective, she must be shriven of her pride to be able to come through, both physically and morally, to the other side. For Rossellini, what is important is the decisive, traumatic moment—the moment when the forces of the universe and the inner soul come into delicate balance and, as in a Words-worthian vision, one is allowed a glimpse into the spiritual heart of things. At one point Karin is uncertainly poised halfway between the world of men and the world of God (Rossellini clearly distinguishes them) and significantly looks up to the crater and then back to the village. Bathed in a magnificent light that makes her radiant against the blackness of the lava, she decides to continue upward, repeating Nanni's gesture in The Miracle , moving ever closer to the rarified atmosphere of the spiritual, away from the earthly. Too many critics have seen her choice as merely one of going on with her individual life or resigning herself to the constricted life of the village, but clearly this is only its secondary manifestation. Rather, the film poses her choice as between continuing to be a selfish individualist or realizing the existence of something higher that transcends and enfolds within it mere social questions of the individual versus the group.

The religious resonance of the ending also becomes clear, for the horrible ascent up the fearful volcano is Karin's dark night of the soul. As the dangerous smoke and fumes surround and choke her, she is offered a literal vision of hell. Throughout this sequence, in close-up after close-up, her wedding ring is greatly in evidence, a constant reminder of the social ties that are calling her back to the village; these ties also pale into insignificance in the face of the primordial power of the volcano. Sobbing wildly, she cries out, "I'll finish it, but I haven't the courage; I'm afraid!" She also cries out the name of God twice, but as an expletive, a neutral verbalization of her frustration and exhaustion (again, like Nanni's "Dio, Dio" at the end of The Miracle ). The image then fades to a more peaceful moment sometime later. The stars are out. The film cuts again a few seconds later to morning and, as Karin wakes up, she blocks the sun with her hand. Again she says, "Oh God!" twice, but now the expletive has been transformed into an act of homage to the magnificent stillness all around her. She touches her abdomen, recalling her child for us, and, looking around, cries, "What mystery! What beauty!" in a way that, to this viewer at least, seems utterly convincing. Through her ghastly trial she now seems to have arrived at a better understanding of her place in the world. Then the film cuts

to a shot of birds wheeling in the sky (presumably symbolic of Karin's spiritual rebirth), a shot that has been prepared for with similar shots of birds flying around in the peace following the volcano's eruption.

It is at this point that the English and Italian versions of the film distinctly divide, and if its finale is to be condemned, it should be Rossellini's rather than RKO's. For some, of course, the very religiosity of the ending, in either version, is cause enough to dismiss the entire film. Those who have been able to accept its spiritual dimension have for the most part, however, objected to Karin's apparent decision to return to the village at the very last moment, totally subjugating her own sense of self to the will of others. In the English version, her return is clear-cut and unambiguous, even praised; in the Italian version, however, the ending is more characteristically ambivalent, and Rossellini refuses to provide a satisfying closure.

In the RKO version, the obtrusive voice-over comes straight out and tells us exactly what to think: "Out of her terror and her suffering, Karin had found a great need for God. And she knew now that only in her return to the village could she hope for peace."[10] While the "uplifting" musical theme soars, the camera cuts between her smiling, beatific face and the village, ending on a slight zoom on the village, within the context of the extreme long shot. Even apart from the obvious sexist wish fulfillment of this ending, it is clearly the forced, explicit naming of the religious theme in this way that has made the final scene so unpalatable to American viewers.

In Rossellini's version, the voice-over is, as throughout the film, completely absent. After Karen cries, "What mystery! What beauty!" the film cuts to a long shot of the mountain. The camera then pans up the mountain, emphasizing its active participation in Karen's religious conversion, and then pans back down to find her. In a full shot, she stands on a small hillock, looking down at the village. The film cuts to the village in long shot and we hear her say offscreen, "No, I can't go back!" Cut back to her. She sits down. Cut to a tight head-and-shoulders shot. "They are horrible. It was all horrible," she says. Cut back to an extreme long shot of the village, pasted on the very edge of the vast sea, another brute power of nature. "They don't know what they're doing," she says offscreen, in one of the Christological references Rossellini is fond of, which would link Karin even more closely to that earlier female Christ-victim figure, Nanni. The difference between the two women becomes immensely clear in the next line, however, for Karin is an intelligent being in full command of her rational faculties: "I'm even worse," she says. Cut to an extreme close-up on her face, as she looks away, disgusted both by the village and by herself. She begins crying, quickly turns her head back, and says, "I'll save him." Cut to a full shot in which she holds her abdomen and says, "My innocent child!" Cut to a close-up as she shouts, "God, my God! Help me! Give me the strength, the understanding, and the courage!" She buries her head, sobbing, then cries more softly, "God, God." Cut to birds flying overhead as the camera pans across the sky. Offscreen, we hear her saying, "My God! Oh merciful God!" (or perhaps "Almighty God!") as the birds continue to fly past. In this version, the film ends with a shot of the billowing smoke of the volcano.

Clearly, what is important for Rossellini is the individual's growth from

selfish ego toward a transcendent spirituality. It is much less important here than in the English version whether or not Karin returns to the village. It is equally possible, of course, to read this ending as the submission of the independent female to the patriarchal authority; but the patriarch here is God, not her husband Antonio or his male-dominated society. In the mid-sixties, Adriano Aprà and Maurizio Ponzi asked Rossellini in an interview if Karin is leaving or returning to the village at the end. He replied:

I don't know. That would be the beginning of another film. The only hope for Karin is to have a human attitude toward something, at least once. The greatest monster has some humanity in him. . . . There is a turning point in every human experience in life—which isn't the end of the experience or of the man, but a turning point. My finales are turning points. Then it begins again—but as for what it is that begins, I don't know. I'll tell that another time, if it has to be told. If things haven't happened there's no point in going on and getting involved in another story.[11]

In a 1959 interview he put it even more directly: "A woman has undergone the trials of the war; she comes out of it bruised and hardened, no longer knowing what a human feeling it. The important thing was to find out if this woman could still cry and the film stops there, when the first tears begin to flow."[12]

Critical orthodoxy on the ending of Stromboli , even in its Italian version, is negative. Most have felt that the ending is simply too abrupt and unprepared for; even the Catholic phenomenologist Henri Agel is lukewarm about it. Nevertheless, I think an argument can be made that various elements of the film (for example, the early scenes with the priest, the fact that the full title of the Italian version is Stromboli, Land of God , and so on), which are perhaps more subtle than the harsh male-female, individual-group clash that occupies the surface, contribute to the rightness, in its own terms, of the film's spiritual resolution. Rossellini has pointed out with some justice that anyone properly attentive to the epigraph from Isaiah in the opening credits would be able to understand how appropriate the ending really is: "I have hearkened to those who have asked nothing of me. I have let myself be found by those who were not looking for me" (Isa. 65:1). Robin Wood is right, I think, to find Karin's conversion "meticulously prepared for," though never specific. Though Wood's essentialist language is somewhat troublesome, he is on the right track when he says, "More than with any other director the essential meaning has to be read behind and between the images, in the implications of the film's movement which rise to the surface only in rare privileged moments whose significance is never overtly explained and which draw their intensity as much from the accumulations of context as from anything present in the image."[13]

Beyond its ending, an even grander chorus of voices has condemned this entire film and, indeed, the entire series of Bergman-Rossellini collaborations. Some, like Mida, have found fault with Bergman, who forced Rossellini to betray his "real interest" in coralità , making him altogether too "intellectual." Others—and this is still the dominant opinion in Hollywood—refuse to concede that Rossellini was up to something altogether different (whether it was successful or not is another question) and blame him for "ruining" Bergman's

career. However, another, more recent view—one that I share—considers these films with Bergman as among Rossellini's greatest, and, in spite of their faults, among the most significant films made since World War II. Andrew Sarris, for example, has said that "Rossellini's sublime films with Ingrid Bergman were years ahead of their time, and are not fully appreciated even today in America."[14] Nor, he might have added, anywhere else. Bruno Torri, in his Cinema italiano: Dalla realtà alle metafore , has perhaps come the closest to accounting for the brilliance of these films, and his remarks provide an important clue to understanding why the young style-conscious critics of Cahiers du cinéma would become their first champions:

They undoubtedly represent the most advanced that Italian cinema was able to produce in those years beyond the paths already travelled. . . . His is a cinema of questions, not answers; and therefore, also under this profile, the heuristic function ("socratic," as has been justly noted) which his films develop brings with it a final step toward the full autonomy of film style, a decisive freeing from the "banal" (and from cultural parasitism) and finally, what counts the most, a major attempt to make the spectator more responsible, since he is now called on not so much to consent or dissent on more or less univocal messages, to pronounce on attitudes and propositions ideologically already known, as to take up on his own behalf the thread of a discourse specifically cinematographic in a concrete and open time, just as any reality is concrete and open.[15]

For better or worse, then, Stromboli and the other Bergman-era films are "pure" Rossellini. The director himself once insisted that Stromboli was important to him, and whoever did not like it had no reason to like any of his other films either.[16]

13—

Francesco, Giullare di Dio

(1950)

At the very height of the scandal, while Bergman and Rossellini were being accused of the most heinous crimes against morality and human decency, Rossellini was busy making the most overtly religious film of his life. Later films like Augustine of Hippo, Acts of the Apostles , and The Messiah are, as we shall see, ultimately more concerned with history than theology or the spiritual life. Francesco, giullare di Dio (Francis, God's Jester) to give it its full title, is delicately poised between the two. Thus, it clearly fits into the religious search and questioning of "crisis-era" films like The Miracle, Stromboli , and Europa '51 , its modern-day "sequel," which immediately followed. At the same time, however, Francesco signals the beginning of Rossellini's interest in the depiction of history per se. (It is also possible, of course, to see Open City, Paisan , and Germany, Year Zero as "historical films" that depict the recent past.)

This new interest in history is obvious throughout the film, but especially in the beginning of the American version (which, unlike Stromboli , Rossellini seems to have been responsible for).[1] There, we are historically situated through paintings and frescoes to give us the proper context to understand what we are about to see. In this, it is similar to the American version of the opening of Stromboli and, of course, the map and voice-over that move us through Paisan .[2] In other words, a strong didactic interest reigns in this film, as in most of Rossellini's films; this impulse is more overt in the later television work, but it is present from the first. Here the frescoes function to create an otherness in time, a past place that the film will consciously seek to represent, to signify, without attempting to recreate the historical period illusionistically. The difference may seem slight, but is in fact crucial and is the strategy that makes many of the

later historical films more epistemologically sophisticated than they seem at first glance. The frescoes, which Rossellini's camera pans while the voice-over explains the historical events they represent, complexly negotiate the distance between the filmic representation of the past and the past itself. They represent the past for us, yet they, in fact, also are the past because they were made then, but continue to exist in our day.

This strategy is characteristic of the whole film, and not just the opening of the American version, for Rossellini has not chosen to represent the historical Saint Francis, but quite clearly, as the opening credits tell us, to base the film on the prior representation of Francis and his followers in the Fioretti (Little Flowers) , first written right after Francis' death. This can, of course, be regarded as an attempt to get closer to the "truth" or "essence" of Saint Francis; but it also is a subtle admission that we cannot really get back to the past, as Ding an sich , but only represent it in ways that will always be more or less "distorted" by previous interpretations of it. As a version of the Fioretti , a genuine piece of writing from the past that continues to exist into the present, the film is both more authentic and yet further removed from real historical events themselves. In the Italian version, this process of mediation is even more deliberately foregrounded, as intertitles taken directly from chapter headings of the Fioretti are flashed on the screen before each new vignette. As we shall see, this general strategy of temporal doubling continues through the later historical films, when Rossellini insists on words and more words drawn from actual historical documents. In a sense, it is really the words, which exist in two times, that make these films "historical."

Rossellini has recounted in several interviews how Francesco came to be made. During the filming of Paisan , the director found himself with three German prisoners who were cooperating with the filming, if rather uneasily, and who finally took refuge in a monastery, where they knew they would be safe. When Rossellini and Fellini went to fetch them, they discovered the lovely shelter that became the setting for the monastery sequence of Paisan . From that day on, both men were intrigued with the idea of using these monks to make a film on Saint Francis himself, a film that would go back to the roots of the innocent naïveté and generosity (even if mistaken) that marks the monastery episode of the earlier film.[3] According to Brunello Rondi, who was associated with the film in its early stages, shooting began with a twenty-eight-page treatment (including only seventy-one lines of dialogue!) that had been worked up by Rossellini and Fellini alone. Fellini told his biographer Solmi that he had personally suggested the humorous scene with the tyrant Nicolaio; nevertheless, the film has always been regarded by those involved as Rossellini's creation. This fact must be insisted upon because of the common rhetorical tactic, used by an older generation of Communist critics to discredit Rossellini's films during this period, of suggesting that the film's "mysticism" and religiosity were the fault of the even more intensely disapproved-of Fellini, who had turned his back on anything even remotely resembling social realism. The screenplay, such as it was, and the rest of the dialogue were written later, during the actual shooting, as was Rossellini's wont, by the director, Rondi, and Father Alberto Maisano, who was in charge of the novices. Rondi has attested that no one else

was involved (in spite of the fact that the credits say that two priests, Felix Morlion and Antonio Lisandrini, also participated in the screenplay), and that at no time was there any church interference with Rossellini and Fellini's original idea. This testimony is important because some have accused Rossellini of making Catholic propaganda in this film; Rondi contends that, on the contrary, ecclesiastical authorities were displeased with the film because of its too-human portrayal of the saint.[4]

As the credits proudly state (hearkening back at least eight years to La nave bianca ), "The actors were taken from real-life," with the exception of Aldo Fabrizi (as in Open City ), in the role of the tyrant Nicolaio. Rossellini preferred working with nonprofessionals, but he never insisted that a real fisherman had to play a fisherman, a real farmer a farmer. Here, however, the coincidence is exact, and the friars are all played by real Franciscans.

When the film appeared, critical reaction was mixed, and it failed miserably at the box office. Interestingly enough, many neorealist critics who had sadly shaken their heads during the period of Rossellini's "crisis" warmly welcomed the film as a return to his "true" theme and mode, coralità , and in fact, an overcoming of the director's proclivity toward mysticism. Marxist critics, on the other hand, with Pio Baldelli leading the charge, attacked it as being little more than propaganda for the Church and, since 1950 was a papal holy year, Rossellini's attempt to get back in the Vatican's good graces.

The extensive polemic surrounding this film has revolved chiefly around the question of its historical veracity to the times, the Franciscans, and the saint himself. The debate is marked, on both sides, by appallingly simplistic notions concerning what it would mean to be historically true to a past epoch, and how one would go about finding a neutral ground from which one could portray the past "in its own terms," or even better, "objectively." Thus, the argument centers around claims of Rossellini's success or failure in this area, rather than the very possibility of presenting history objectively. It seems clearer today that the film offers itself, through the intermediary of the Fioretti , rather as a reading of history, of history as a text that cannot be grasped in a direct and unmediated form. At this point, at least, Rossellini seems to realize that all interpretations must be subjectively based, like all depictions of "reality," whether they are of an earlier era, or, as we shall see in India , of an alien culture.

But Rossellini would have refused to make the next step, toward either the utter unknowability of history or a radical relativism. In the later historical films, in fact, where more is at stake, he even wants to elide the subjective element altogether in favor of an "unbiased" presentation of facts. Rossellini also subscribes to an idea of history composed in grand outlines of major turning points, shifts in consciousness—a view of history that is itself, of course, only another interpretation. Thus, in Francesco he is not trying to portray merely a specific saint and his way of being in the world—though he is doing that as well—but also, as in his later historical films, what he takes to be a turning point in world history. Similarly, the title's emphasis on the person of Saint Francis is itself belied, for from the very beginning of the film—when for the longest time Rossellini refuses to single out Francis—great pains are taken to decenter the saint, to see him as a member of a group and as part of an era. (Some critics

have complained that Brother Ginepro, the foolish monk around whom many of the unconnected episodes revolve, is accorded too much importance in the film, at the expense of Francis, but it is clear that this is a crucial and conscious tactic.) Rossellini's later historical films will repeat this contradictory double stress on the individual and his time: films like Augustine of Hippo, Pascal, Socrates , and so on all point, even in their titles, to a "great man" theory of history, but since the individual figures serve in the films chiefly as organizing devices for the presentation of the characteristics of an age, the theory is at the same time undone.

Of earlier critics, Mida seems closest to a proper sense of Rossellini's historical relativism. For him, the interpretation of Francis is rather "loose" and poetic, but he prefers this to a cold recital of facts: Rossellini "is faithful to history, but it is a faithfulness that must be understood through the fantasy of an artist, who takes everything from the legend which inspires and moves him."[5] Later critics like Jose Guarner have rightly insisted that the historical recreation has been whittled down to a recreation of ideas; and Giorgio Tinazzi has pointed out, the principal idea here is "Franciscanism as a way of existence."[6] In other words, Rossellini's interest in the depiction of history primarily for its informational value is not nearly as developed as it will be later in the films made for television. Here, he remains a captive of the religious impulse of films like The Miracle and Stromboli[7] (remember that Saint Francis was also mentioned in Rossellini's first letter to Bergman), and Francesco serves retrospectively as a grounding for the relentless spiritual striving of these earlier films.[8]

But if religious values are privileged over the "facts," Rossellini nevertheless had a didactic purpose in mind in making this film. As in the other films of this period, he is concerned with the despair and cynicism facing postwar Europe, and unashamedly offers Saint Francis and his philosophy as answers, as a way back to an essential wholeness. Just as the turn to God at the end of Stromboli may embarrass us nowadays with its overt religiosity, so too the "message" of Francesco is militantly old-fashioned, as Rossellini told students at the Centro sperimentale di cinematografia in the early sixties:

It was important for me then to affirm everything that stood against slyness and cunning. In other words, I believed then and still believe that simplicity is a very powerful weapon. . . . The innocent one will always defeat the evil one; I am absolutely convinced of this, and in our own era we have a vivid example in Ghandhism. . . . Then, if we want to go back to the historical moment, we must remember that these were cruel and violent centuries, and yet in those centuries of violence appeared Saint Francis of Assisi and Saint Catherine of Siena.[9]

Marcel Oms may claim that one does not vanquish tyrants by nonviolence, as Brother Ginepro does in the Fioretti and the film, but Rossellini clearly feels otherwise. Revolutionary after his own fashion, the director believes, with Shelley, that the individual must first be changed before society can be changed. Naturally, this can seem to be the kind of phony "revolution" always fostered by the bourgeoisie, who speak of spiritual values rather than material ones be-

cause their material lives are relatively comfortable. In any case, it obviously took courage for Rossellini to offer such transparently "retrograde" values to a modern audience, and in many ways the radicalism of this film lies in its fearless exposure of the director's vulnerable idealism. As we shall see, this courage is even more evident in his next film, Europa '51 , which carries the same message as Francesco but removes it from the comfortable safety of the distant past to the startling present of its title.

In formal terms, Francesco is a film whose thoroughgoing unconventionality makes the polemics surrounding its historical veracity almost irrelevant. For one thing, there is really no plot in the film, and scarcely more characterization. It revels in the partial, the hint, the barely glimpsed, shunning the fully "narrativized" or the straightforwardly presented. Aside from Brother Ginepro's violent encounter with the tyrant Nicolaio and his men, we get little more than humorous misunderstandings about needing a pig's foot to make soup (Ginepro "convinces" a still-living pig to donate its foot), Saint Francis telling the birds to be quiet so that he can pray, and the loving, simple preparations for the visit of Saint Clair. Again, as we have seen in other Rossellini films, the sketch, the vignette, and the illuminating anecdote are favored over a doggedly linear exposition. The individual scenes from the Fioretti chosen for "dramatization" do not seem inevitable, nor do they really cohere (as some have complained), but, then again, they were never meant to. Rather, an atmosphere is created and a minimalist structural system of opposites elaborated in a denuded and thoroughly unrealistic setting. As part of this strategy, the process of symbolization is foregrounded throughout in the constant references to the purgative emblems of fire and rain. The monks' full-throated Gregorian chant, which links many of the vignettes, also contributes to the purposeful lack of realism, for it was obviously recorded by a large choir singing in a church. Similarly, gestures and other movements of bodies and heads are greatly slowed down, further stylizing the film in the direction of greater simplicity. What is at stake, once again, is an idea rather than an illusionistic reconstruction.

History, or better, historiography, on the other hand, is linear, fully elaborated, logical, supremely rational. There are beginnings and endings and—at least to judge by the work of most historians—clear-cut narratives, with the rising action, falling action, and climax all properly arranged, according to the neat codes of realism, no matter what violence may be done to the actual fabric of lived experience. In other words, in the depiction of the "divine madness" that afflicted Saint Francis and his followers, it was important to Rossellini in 1950 to avoid the rigors of a supposedly objective historiography because its logical linearity would itself have been inimical to the Franciscans' crazy world of faith. As Henri Agel has reminded us, these early Franciscans, thought eccentric, were simply disaffected with the power of rationality that we hold so dear. In this regard he compares Rossellini's film to Dreyer's Ordet: in both, "Faith blows up all the logical mechanisms."[10] Elsewhere, Agel says of Francesco that it demonstrates "a perfect disaffection of the soul vis-à-vis the mental processes of a civilized adult."[11] Thus, an "accurate" historical recreation will be one more logical mechanism that Rossellini must blow up if the film's form is to reflect its subject matter.