9—

Una Voce Umana

(1947–48)

Rossellini's next film, of an awkward thirty-five minute length that forced him later to pair it with The Miracle in order to make it commercially feasible—they were released together as L'amore in 1948—is based on La Voix humaine , a one-act play by Jean Cocteau. Disparaged or avoided by most critics, the film is actually thematically and philosophically complex, even if its subject—the rejected woman—may not be particularly palatable, especially thirty-five years later. The realist-expressionist tension of Germany, Year Zero continues, but now the focus is so obsessively on the individual that nothing else remains. As we have seen, in Germany, Year Zero Rossellini appears to have lost faith in the coralità that animated the first two films of the postwar trilogy, turning back instead to the lone individual, as in L'uomo dalla croce , who tries unsuccessfully to make his or her way through a hostile world to personal salvation. If the group had lost its moral force in Germany, Year Zero , however, the environment still reigned supreme, a clear determinant of behavior. In Una voce umana (A Human Voice), not only does the group disappear—for no one other than the main character (played by Anna Magnani) is even seen or heard, except by inference—but the environment disappears as well. (Curiously, the presence of a dog serves to heighten the woman's isolation even more, rather than relieve it.) In this film, transcendence is no longer even a theoretical possibility. We are locked in a woman's tiny apartment (actually, the bedroom and bathroom) while she has her last telephone conversation with the lover who is rejecting her for another woman. That is the whole of the plot.

Coralità is now reduced to a single other voice, the lover's, of which we can just faintly hear the hum. Also barely noticeable are the sound effects of starting

cars, a party, a crying baby (the last two clearly symbolic), which arise between calls. But the woman rejects all others, for they are just "people," who do not understand them and their love. The lovers have alienated themselves from human community because they have lost their reason, as Rossellini might have put it twenty years later, just like Edmund in the horrible act of murdering his father. In the earlier film, however, language is still a sign of human community, and when Edmund is ostracized (or ostracizes himself), language disappears. Here, however, we see language's other side: a means of falsifying feelings, the site of the struggle for mastery of one human over another, the place where narcissistic self-absorption can make the whole communal enterprise meaningless. We hear a slight buzzing at the other end of the line, signifying for us the presence of another human being, but that "presence" is actually constituted only differentially by Magnani, as a kind of sick projection of her own ego. (It is symbolically fitting that we hear only the lover's mumbles and murmurs, absent of human meaning.) In fact, we are only able to infer what he says through her responses. In the play version the audience hers nothing of the man, not even the murmurs, and in his preface Cocteau maintains that the actress is really playing two roles: one when she speaks, and the other when she listens and thus "delimits" the other.[1]

In Una voce umana the authenticity of words is no longer guaranteed: when Magnani is apparently asked what she is wearing at that moment, she constructs for her lover a portrait that is completely false. She also lies by saying that she has been taking the whole thing very well, when she is in fact on the verge of a breakdown. He, too, is lying, for though he is obviously calling from his new lover's apartment, he insists (we infer) that this is not the case. Lying is, in fact, directly thematized, or rather, the incommensurability between language and the external world. As such, the rhythm of the film proceeds in exactly the opposite direction of that of Germany, Year Zero , which moves from language toward its absence. Here the beginning is played out in almost dead silence: there is only isolation and the naked self, and we wait for this silence to be filled by the community of language. When it does come, in an annoying barrage, it is entirely rhetorical and overemotionalized—pure artifice, barely referential. In the largest sense, Rossellini is probing the nature of linguistic and, by extension, cinematic representation and its adequacy to the real world. He seems to have become more consciously aware that one cannot get to nature through culture (language, film) without that "nature" being profoundly altered. Una voce umana thus becomes a meditation on this very notion; if artifice cannot be avoided in one's pursuit of "reality," then perhaps one had best embrace it openly. Rossellini always spoke of this film as an "experiment," but he seems to have regarded the experiment as inconclusive or worse, and perhaps better forgotten. The Miracle , as we shall see, is precisely this forgetting, for in it both the environment and the group are reinstated and, in the best tradition of realism, the problems of representation are once again elided.

In his 1955 article in Cahiers du cinéma entitled "Dix ans de cinéma," Rossellini gives us a sense of the complexities of this film:

The cinema is also doubtless a microscope. The cinema can take us by the hand and lead us to discover things that the eye couldn't even perceive (for

example in close-ups and detail shots). . . . More than any other subject, La Voix humaine gave me the chance to use the camera as a microscope, especially since the phenomenon to examine was called Anna Magnani . Only the novel, poetry, and the cinema allow us to riffle around in the characters to discover their reactions and the motives which make them act [my emphasis].[2]

A dual perspective seems to be operating here. On the one hand, the film is an intensely emotional story portraying a woman's psychological state at being spurned by her lover, while on the other, it is a thoroughly self-aware, simultaneous dismantling of that story.

On the first level, Rossellini, following Cocteau, has tried to present a believable, but universalized, portrayal of a woman of "this sort." The film thus continues the grand project, begun in earnest in Germany, Year Zero but hinted at earlier, of the discovery of the individual self, and the claustrophobia and implacable camera of the previous film haunt Una voce umana as well. Here the portrait is not very flattering: the woman is seen as utterly emotional, unable to get her feelings under control, suicidal, totally dependent on the man's will. Clearly the product of an earlier day—Cocteau's play was first performed on February 17, 1930—it is, perhaps not surprisingly, still being revived, most recently by Liv Ullman. Ironically, when he made the film, Rossellini said he wanted to show the truth—that women were so often the victims of men—but the film also serves to reinforce the stereotype of woman as eternal victim.[3] Here he seems largely to have followed his source, for the misogyny of victimization is adopted directly from Cocteau's play, as is the tale of attempted suicide recounted by the woman. The image near the end of the film when the actress wraps the telephone cord around her neck in symbolic self-destruction, after making much of the fact that her lover's voice is in the wire, is also an explicit stage direction in the play. Cocteau's misogynistic violence is at times even more blatant than that, especially, for example, when the "author" suggests to the actress in the play's preface that "she give the impression of bleeding, of losing her blood, just like an animal which is limping, of finishing the act in a room full of blood." Earlier in the preface, Cocteau has spoken of the room as a scene of murder.

There is another level to Rossellini's film, however, and what redeems it, at least on an aesthetic plane, is its brilliant self-awareness. The director's insistence, quoted above, that "the phenomenon to examine was called Anna Magnani," is manifested everywhere in the film and virtually ensures that it will be intensely aware of its own artifice. So, for example, the film is expressly dedicated in its opening credits to Magnani and her "great artistry," immediately underlining her own presence and her function as representation, and thus helping to delay the spectator's belief in the fiction of her screen character. Once the film begins, intensely long takes from a seemingly immobile camera predominate, foregrounding Magnani's tour-de-force performance with the help of dialogue that calls attention to itself because it is so obviously overheated. Some of her lines are even repeated six or seven times in a row, calling upon the actress's utmost skill to sustain the high level of emotion and to offer sufficient variation in expression and intonation to keep the audience interested. (In the film version, in fact, the emotion has been purposely heightened beyond Cocteau's original, which lacks the final breakdown scene.) At other times, the

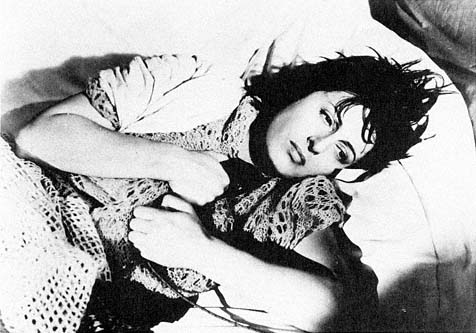

Self-reflexive tour de force: Anna Magnani and telephone in Una voce umana (1948).

scene is even played with Magnani's back to the camera, so that her voice and sheer presence must carry the whole. In this latter instance, it seems as though a technically "bad" shot is deliberately retained to raise the stakes and the level of challenge for the actress. The stolid immobility of the furniture serves further to push her to the fore.

Thus, while the worst proclivities of "rhetoric" (as Italian critics call it) are being yielded to, the paradoxical effect is that the film betrays and reveals its artifice by keeping us always aware of the real woman's presence. On one level, in other words, it attempts to create an illusionism that would make us psycholocigally substitute the person of the actress for her character, while on another level it blocks this attempt. Una voce umana thus sets up an ontological identity between the actress and the character she is playing, intermittently collapsing the two categories while it deconstructs its own surface realism by means of the preexisting reality of Magnani herself. (Appropriately, the dog in the film was Magnani's dog and is called by its real name). Like the British soldiers of Germany, Year Zero , whose very reality as British soldiers created a "stylized" element that could not be successfully assimilated into the film's coded realism, Magnani's acting in Una voce umana stands the process of realistic representation on its head.

Nor is this project peculiar to Rossellini's version, for it is obvious from Cocteau's preface that he also conceived of his play as a kind of challenge or experiment, of theater stripped to its essentials (and thus inevitably self-aware).

He makes it very clear that he is not interested in psychological problems, but wants to "resolve problems of a theatrical order." He would have called it "pure theater," he says, if that phrase were not a pleonasm. Even more important, he says he wrote the play as "a pretext for an actress," since he had been previously reproached for always putting himself over his actors.

Other elements in the film increase its self-awareness as well. For one thing, we are regularly subjected to jump cuts that are almost as jarring—and as purposeful—as those of Godard's Breathless . The director also often leaves his signature within a shot as, for example, when we see a microphone dangling into the frame. This is an amateur's mistake, of course, the mistake of a director who was, according to Adriano Aprà, shooting with live sound for the first time in his career. Yet it is tempting to see this exposed microphone as one more sign of the director's presence, unconsciously signaling the artifice that he is creating. Mirrors also constantly function in this film in a self-reflexive way: in fact, the very first shot is a close-up of Magnani's mirror image, from which the camera then pulls back to reveal it for what it is, a reflection of a reflection (which it can only do differentially, by showing something external, that is, what it is not ). At other points, there are three or four mirrors in evidence in a single shot, all reflecting one another, further heightening the claustrophobic, abyssal mise-en-scène and further underlining the presence of the artist and the refusal of realistic illusionism.

What results from this strange mixture of misogynism and self-reflexivity is a complex sexual dynamic. For if "the phenomenon to examine was called Anna Magnani," the rather ruthless examiner is Roberto Rossellini. He is the lover at the other end of the line, of course, just as he is, in some ways, the various complex husbands that Ingrid Bergman will do battle with in Stromboli, Voyage to Italy, Europa '51 , and Fear . What complicates things is that he is also their creator.