I—

BEFORE OPEN CITY

1—

Early Film Projects

Born on May 8, 1906, in Rome, the city that was to figure so importantly in his films, Roberto Rossellini was the first child of wealthy parents. Twenty months later, Roberto's birth was followed by that of his brother Renzo, who was to compose most of the music for Roberto's films and become a highly regarded composer in his own right. A year or so later came Marcella and then, apparently as an accident, Micaela twelve years after that.

According to Marcella, their childhood was "simply marvelous."[1] She readily admits that they were all thoroughly spoiled, the beautiful Roberto, as the oldest, perhaps even more than the others. The Rossellinis were among the first in Rome to own an automobile, and the various palazzi in which they lived always included enough room for a chauffeur, cook, butler, maid, and their mother's personal servant. Roberto ruled the game room, which their indulgent father had filled with an immense wooden battlefield complete with Italian and Turkish lead soldiers (this was the time, just prior to World War I, when Italy was contending with Turkey for control of Libya). Roberto, the aggressive, dominant figure, always claimed the Italian soldiers, while Renzo, frailer, more introspective, and—even by his own later account—unhealthily dependent on his brother, would be stuck with the Turks. Marcella willingly served as Roberto's "little slave."

There is no doubt that growing up rich had a great impact on the future director's life and films. Some reproached Rossellini later on, especially when it became fashionable to speak of his abandonment of neorealist principles, for not having had the proper background to understand the poor people who were the orthodox subjects of neorealist films. Others have suggested, with equal plausi-

bility, that his privileged childhood and consequent disdain for money account for his lifelong battle with the compromises of commercial cinema. In any case, it is clear that Rossellini made few artistic decisions based on money.

From a young age enormously attracted to mechanical things, Roberto established a small workshop in the attic of their building, where he busied himself inventing things, readily receiving financial assistance from his father, who was clearly the most important influence on his childhood. A successful builder, like his father before him, he had been mortally infected by the germ of culture and for years harbored the dream of becoming a novelist. In his autobiography, Renzo Rossellini describes how his father would sometimes get up in the middle of the night to write, or try to write, until it was time to go to work in the morning. Years later, in fact, Renzo was still upset by his father's torment over writing and remained convinced that it contributed to his premature death at age forty-nine. His novel was published just before he died but, unfortunately, went unnoticed.[2] Roberto himself would later think of becoming a novelist, but more out of the desperation caused by his initial inability to raise funds for another film after Open City than in imitation of his father. It is clear that the cinema—that unique hybrid of the artistic and the mechanical—would be a more appropriate place for this lover of culture and the intellectual life who was no less enamored of science and technology.

But if Roberto's father could not fulfill his dream of becoming a writer, he "felt like a poet and lived like one" on Sunday afternoons, when all of his intellectual friends dropped in to discuss each other's work and debate the great aesthetic matters of the day. The children would be allowed to listen, and all of them remember it as the most exceptional schooling imaginable. According to Renzo, the men were much influenced by the Croceans in the group, whose aesthetic exalted the romantic notion of art as self-expression, an aesthetic that Rossellini, as an adult, would utterly reject. It is clear that this sort of learning by discussion, in bits and pieces over a wide range of topics, set the pattern for Rossellini's lifelong intellectual habits. Never having completed a unified educational program of any sort—again, perhaps, because his family's wealth made preparation for a career seem superfluous—Rossellini's immensely varied learning nevertheless astounded everyone he met throughout his life.

Roberto's halcyon childhood was marked by only one blemish. When the influenza epidemic stalked the world immediately after the end of World War I, everyone in the family contracted it. Roberto was afflicted most seriously and hovered between life and death for some months. Marcella recounts how her elegant, refined mother, overwhelmed by the apparently imminent death of her firstborn, made a vow that if he came out of it alive she would wear only black the rest of her life. When Roberto recovered, she kept the vow.

From his sickbed, Roberto was for perhaps the first time in his life dependent on Marcella, who would bring him anxiously awaited reports each week on the latest exploits of whatever movie serial hero was their current favorite. The children had become enamored of the movies because of a marvelously fortuitous circumstance: their father had built two of the most elaborate theaters in Rome, the Corso and the Barberini. This entitled them to free access, and Roberto quickly became the scourge of both managements because he would in-

sist on bringing along twenty or thirty of his and Renzo's sailor-suited, spirited classmates from the Collegio Nazareno.

It is not clear how Rossellini became seriously interested in the cinema, at least beyond these paradisal teenage days of free viewing. In later years he was to confess to having been struck by Vidor's films The Crowd and Hallelujah , and the early version of The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse . He told the Italian film critic Pio Baldelli and his students in 1969 that he went to the movies constantly as a youth and was especially impressed by the work of Griffith and Murnau. He also recounted a scene from The Crowd in which a character, nervous about meeting his bride's family, forgets to wipe a bit of soap from his earlobe after shaving: "These things struck me and perhaps put me on the road of truth, of reality, no?"[3]

It is clear that Rossellini never made a conscious, specific decision to become a director, but instead drifted into it the way rich, idle young men are apt to drift into things. His sister Marcella thinks it was because he was in love with the well-known actress Assia Noris. Already a notorious playboy, Rossellini hung around the studio and ended up doing sound effects and some editing, and writing parts of screenplays.[4] He began making short documentaries with his own money, perhaps simply to master a new territory. Next to nothing is known about most of these short films, unfortunately, since all but one have long since disappeared. Massimo Mida, who wrote the first full-length treatment of Rossellini's films in 1953, says that the director began experimenting with his new toy as early as 1934. By the mid-thirties he had produced two short films on nature subjects: Daphne , about which nothing seems to be known, and Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune . The latter, Rossellini was to point out in later years, was not a filmed ballet, as the title might suggest. Rather, the film was inspired by his closeness to nature and by Debussy's music. According to Mida, it was never projected in Italy because the censors had decided that a few of the shots were indecent. Mida feels that even in these slight documentaries Rossellini was demonstrating his "revolutionary" new vision of life, simply by refusing to make the standard tourist landscape documentaries and instead turning directly to nature.[5] Rossellini told Mario Verdone in 1952 that, in one of these early shorts, he "was struck by the water with the serpent slithering about in it and the dragonfly overhead. It's the kind of sensitivity you see in the puppies on the main deck in La nave bianca , or the flower caught by the sailor as he disembarks."[6]

Refusing to be discouraged by the Fascist censorship of Prélude , Rossellini went ahead with plans to set up a complete studio in his family's summer villa outside Rome. It was here that he made his next short, Fantasia sottomarina (1939), which Mida calls his best, and which, in any case, is the only one still extant. The story, if one may call it that, concerns the vicissitudes of some fish and other underwater denizens that Rossellini staged in a large aquarium. He admitted to two Spanish interviewers in 1970 that the fish were sometimes moved by strings (Mida says by long hairs) "because we were filming in an aquarium and some fish died very quickly, so that for some scenes we had to manipulate them like puppets."[7] This apparently throwaway answer indicates, I think, that Rossellini, at least at this time, was not moved by any special sensitivity to na-

ture, which presumably would have made him upset about the fish he was killing, but rather by a simple and absolutely implacable desire to understand how things worked. The film took a great deal of time and effort to put together, was sold to Esperia Films, and, given the modesty of its means, was quite successful.

If an absolute veracity is demanded, this little film will disappoint: since Rossellini's camera pans but is unable to dolly or move in depth, given the limitations of the tank, alert viewers will quickly become aware that they are not really on location in the briny deep. Immediately noticeable as well is Rossellini's heavy reliance on montage, given the later fame of his long take. Here he unreservedly uses crosscutting to provoke a sense of conflict and suspense—in this case between an octopus and the fish it is about to strike, and later, when some larger fish, in turn, attack the ink-squirting octopus. And he has somewhere learned about film's basic potential to deceive, for his cuts often suggest a particular action that we never quite see. Further on, the cutting becomes feverish when the wounded octopus is attacked by hundreds of smaller fish who sense its vulnerability.

The music, by Edoardo Micucci, is also tightly keyed to the editing to allow for the maximum in "thrills," an aim that Rossellini's later aesthetic will denounce. When the various creatures are introduced to us, the music is the sort of impressionist composition that convinces us of the idyllic, easy harmony of nature. Later, when open struggle has broken out, the music matches the frenzy of the editing and at one point even sounds like a kind of Morse code that warns away the smaller fish. The principal struggle between the octopus and what appears to be a moray eel serves, interestingly enough, more as a focusing device than as the real subject of the film. Though the reliance on close-ups is extensive, Rossellini generally takes pains to stress the overall ambience and the complex interrelations among the various species. Hence, the coralità so often stressed by his early admirers—Rossellini's choice of portraying the collective group rather than concentrating solely on the main figures—perhaps can be seen here in embryo.

One other aspect of Rossellini's later films in evidence here is an interest in lighting and shot composition for their own sake—an interest that, in spite of his continual denials, persists in a subdued fashion throughout his career. Rossellini's focus, of course, is on presenting the reality of these fish as best he can (even if it means, paradoxically, a bit of trucage here and there in his watery studio), but the creatures also clearly function as abstract elements of a formal composition.

At the end, the octopus escapes the fish, lobsters, and crabs that have been tearing at it, and the music reverts to the sweet melodies heard in the film's beginning. Strong light comes from the right, beautifully modeling the fish and perhaps suggesting the end of day, and then becomes a dramatic, but peaceful, backlighting. Near the end, several fish come together, and harmony is restored. The final shot, beautifully composed, is of two fish of the same species who slowly swim toward each other. One is above the other, and their heads point toward the center of the frame, perfectly perpendicular to the camera. The composition suggests an aesthetic stasis that symbolizes the reigning natural stasis; once this is achieved, we fade to "The End."

After the small, but encouraging, success of Fantasia sottomarina , Rossellini went on to make three other short nature films, Il tacchino prepotente (1939), La vispa Teresa (1939), and Il ruscello di Ripasottile (1941), none of which survive. (Two of their titles signal their subjects, an overbearing turkey and a babbling brook; La vispa Teresa means simply "The Lively Teresa.") What is perhaps finally most significant about this early period—at least as far as one can judge by Fantasia sottomarina , whose very title points to the fact that Rossellini's reality is always informed by the imagination—is the tentative emergence of a dialectic between the facts of the real and a personal interpretation of these facts. We shall have to address these concepts more closely later on, but it is clear that Rossellini understood from the first that neither could exist without the other. Mario Verdone has said of these films: "They don't go only in the direction of a simple photographic recording, but also allow for a personal and poetic creative interpretation. These are the same qualities which will emerge even more clearly in Rossellini's later films, where creation, lyricism, and personal interpretation almost always arise from the document, from the world that we know, from man, from the epoch itself."[8]

It was about halfway through this period of making documentary shorts that Rossellini got his first real opportunity in the world of cinema, when he was asked to collaborate on the screenplay of Luciano Serra, pilota , a film ostensibly directed by Goffredo Alessandrini and released in 1938. One of the most popular films of the entire decade, it shared the prestigious Mussolini Cup with Leni Riefenstahl's Olympia at the 1938 Venice film festival. It concerns the exploits of a young pilot, Luciano Serra, who, disillusioned at the end of World War I, abandons his family and goes off to South America for nearly fifteen years. There he becomes a kind of flying adventurer, but when Italy gets involved in the war with Ethiopia, he returns, at age forty, to help his country. His son, whom he has never known, has also become a pilot; the younger Serra is killed attempting to protect the train on which his father is traveling, unknown to him, from an Ethiopian attack. Sergio Amidei, Rossellini's great collaborator on Open City , whose relations with the director were later to be marked by some bitterness, has insisted in a discussion of Rossellini's "sins" that "Luciano Serra, pilota was a film produced by Vittorio Mussolini, supported by his father; it was a Fascist film."[9]

Actually, the situation was more complicated than Amidei would have us believe. It is true that Mussolini's son Vittorio, an avid flier, came up with the idea for the film, and it is also true that he and Rossellini were friends. But even most anti-Fascists who knew him felt that Vittorio was really a "good guy"—progressive-minded and actually rather embarrassed by his father. He had become greatly attracted during this period to the filmmaking industry, had worked as a producer and screenwriter behind the anagrammatic pseudonym Tito Silvio Mursino, and had been set up as editor of the avant-garde journal Cinema . This government-sponsored journal, published in Rome, was later to prove of enormous importance to the beginnings of neorealism. It was in the pages of Cinema , in fact, that the first calls for a return to the scenes and concerns of "real life" were heard, and within its editorial board that Visconti's revolutionary project Ossessione was born.

Luciano Serra, pilota did indeed have the Duce's support as well. Both Vittorio Mussolini and Ivo Perilli (a popular screenwriter and director who was to work on the script of Rossellini's Europa '51 ) have agreed in interviews that the treatment for the film was approved by the elder Mussolini after his son read it to him while he was shaving, and that it was the Duce, surprisingly, who came up with the rather simple, straightforward title that replaced other more rhetorical suggestions.[10] Rossellini is traditionally listed as coscreenwriter, but recent interviews with many of those involved present a rather more confusing picture, and the nature of Rossellini's participation in the making of this film is unclear. Alessandrini, as might be expected, tended to play down Rossellini's role, claiming that he put Rossellini to work on the script with Vittorio Mussolini because he felt sorry for him. On the other hand, he insisted that if the film had a political message, it came from the screenwriters and not from him.[11] Amidei maintained, on the contrary, that "Rossellini was making Luciano Serra, pilota with a sort of second team, grabbing the film from Alessandrini, who was in Africa; Rossellini, in Rome, was doing things his way."[12] Rossellini spoke vaguely of his part in the film, as he did of all his pre—Open City work: "You must remember what the cinema was in those days. Its ritual was complicated: if you didn't wear the tiara on your head, have the staff in your hand, the ring, the cross, then you didn't make films. . . . Film was a rite which was continually celebrated, and so you could watch the rite, but not enter it and do it yourself."[13] In the more detailed interview with Baldelli, however, he stated flatly and unconvincingly, "It's a film by Alessandrini, and I did absolutely nothing on it."[14]

One of the reasons for this indirection and faulty memory, of course, is the desire to disclaim any closer connection than he needs to with yet another Fascist-era film, especially one conceived by the Duce's son and titled by the Duce himself. Yet like Rossellini's other films of this period, as we shall see, this film is not openly propagandistic in favor of the regime. Fascist ideology in Italy was never as well formed as its counterpart in Nazi Germany; instead, leftists and rightists, priests and atheists, futurists who decried Italy's obsessive regard for its past and imperialists who dreamed of reestablishing that past on a scale that would rival ancient Rome all found something they could associate with in that mess of porridge known as fascism. Hence, Italian films seldom vaunted the Fascist party itself, or its hodgepodge "ideology," which was really little more than belligerent attitudes and rhetorical posturing. Instead, the accent was on nationalism, patriotism, loyalty, bravery, and, above all, efficiency, especially in terms of Italy's preparedness for war. Certainly, some of these films had an offensively martial air—but again, unlike Nazi films, the accent was on the excellence of the Italian fighting units and the durable values that motivated them, rather than on the denigration of enemies like the blacks conquered in Ethiopia. Edward Tannenbaum reports in his Fascism in Italy that even the Istituto LUCE, which had been established by the government precisely to make propaganda films, restrained itself in this area.[15] For instance, he gives this account of Il cammino degli eroi (The Heroes' Road), an hourlong view of the war with Ethiopia, which he considers the most effective documentary LUCE ever produced:

At no point are Ethiopians ever shown, even in the few war scenes. The whole tone is that of a well-planned civilizing expedition. Technically, the film is excellent and, for this type of documentary, very convincing. There are happy, busy soldiers, to be sure, but the film is not sentimental or moralizing. The predominating images are of efficiency and modernity, rather than heroism.[16]

It could also be argued, however, that in many ways this sort of sanitized view of war and imperial conquest is even more harmful because it substitutes a fascination with technology and process for the human reality of pain and suffering, but at least the enemies' absence guarantees that they will not be portrayed as subhuman.

Clearly, this and other war "documentaries," and especially Luciano Serra, pilota and Rossellini's three fictional war films made prior to Open City , are important forerunners of neorealism, primarily for their accent on the sheer facticity of men and machines. As Adriano Aprà and Patrizia Pistagnesi say in an overview of Rossellini's pre—Open City films: "It is not surprising that he relied on the cinema of propaganda, in the 'soft' version (as compared with Nazi cinema) propounded by Luigi Freddi and realized through Vittorio Mussolini, since this is the most explicit manner in which the Fascist cinema dealt with contemporary life."[17] This is simply true: the only other possibilities for making films at this time would be the highly formalized "calligraphic" literary adaptations of Castellani and Soldati, historical costume dramas, melodramas, or the infamous "white telephone" pieces of fluff, those popular bedroom farces (named after one of their ubiquitous props) that crowded Italian screens. One clear purpose of all these films, like so much Italian popular culture during the Fascist era, was to cover over reality, to hide any unpleasantness, to propagate the simple message that under fascism everything was getting better. Stories about crime, for example, were much more heavily censored than critiques of the regime in the daily newspaper, all to protect the great lie. Thus, it could be argued that the war films—both documentary and fictional—provided at least some access to the "real" that filmmakers and writers were hungering for, and which is usually given as the reason behind the tremendous push toward realism that was to make postwar Italian film famous throughout the world.[18]

Nevertheless, it is also clear that these war films served the same function as the other genre films, finally, and did so even more convincingly because of the appearance and trappings of reality that they displayed. Thus, by concentrating on the efficiency and modernity of the troops, the message was being sent that in yet one more area of life the Duce had been good for Italy; at the same time, the absence of any actual fighting kept the audience anesthetized to its real costs. For one thing, this portrayal of the Italian armed forces was far from the truth. Italy's armies were woefully unprepared for war and were in fact overcome on all fronts only a short time after entering the conflict on Germany's side in June 1940. But even more important than this factual, technical lie is the message that war is simply a neutral, technological area—like clearing the Pontine marshes or making the trains run on time—a message that offered more fantasy, disguised this time in clean and pressed uniforms, shining guns, and impressive tanks. As Georges Sadoul has concluded in his Le Cinéma pendant la guerre: "The for-

mula real locations, real details, real characters arrived at infinitely graver lies than the obvious mistakes of crazy sets in the studio."[19]

This much can be said of all these films, including Rossellini's trilogy. But perhaps the indictment should be even stronger in the case of Luciano Serra, pilota , especially if the film is read symbolically, beyond the specificity of its factual and object-laden "reality." Vittorio Mussolini himself considered it a parable of Italy's defiance of the League of Nations: "The film vividly symbolizes today's Italian, who was beaten and then won out over fifty-two nations."[20] Director Alessandrini has spoken of Luciano Serra as a product of the discontent that flourished after World War I, that feeling of being lost, of never finding again what one had experienced as a man at the front. But now, "Italy had found its road, right or wrong," and Luciano returns from exile to find his son in Ethiopia.[21] Tannenbaum neatly sums up the film's thematic implications:

A good case can be made for the argument that Luciano Serra, pilota had a more specifically Fascist message than conventional patriotism. As one critic has put it: "The confusion, the perplexity of the character who is transformed from a negative to a positive being is really the confusion and perplexity of the country, which Fascism [allegedly] banished, salvaging all the national energies—including those that had deviated or gone astray—for a destiny of greatness achieved by a heroic act in which the objective and the subjective are reunited." It was all very well for the ideal Fascist hero to have a bronzed skin, a body of granite, a will of iron, but most Italians could not identify themselves with such an ideal. A much more insidious and effective technique of propaganda was to encourage them to identify themselves with an ordinary and even confused man who finally does the right thing. Luciano Serra, pilota was the best made and most popular film of this type.[22]

This film, therefore, while perhaps not blatantly pro-Fascist, was clearly inscribed in a certain Fascist discourse, marked by an "official," if unstated, view of Italian history and fascism's beneficial role in that history. Nevertheless, as we have seen, it is finally impossible to fix the extent of Rossellini's participation in the film. In order to determine just how politically compromised Rossellini's early career actually was, we will now have to turn to those films in which he played a more overtly active part: La nave bianca (The White Ship, 1941), Un pilota ritorna (A Pilot Returns, 1942), and L'uomo dalla croce (The Man of the Cross, 1943).

2—

La Nave Bianca

(1941)

In early 1941 Rossellini was approached by Francesco De Robertis, head of the film section of the Italian Naval Ministry, to direct a film, under De Robertis' supervision, about the efficiency and modernity of the Italian navy. De Robertis had had an enormous impact on Italian film earlier that year with his innovative Uomini sul fondo (Men on the Bottom), a fictionalized documentary of the lives of men on a submarine. His aim had been to make a didactic film on the Italian navy's superiority in rescue work, and since the film was meant to give information, yet was cast in a fictional form, it was something of a novelty. Obviously, it made a great impression on Rossellini and would prove to be a significant influence on his work. Yet Mario Bava, who worked with Rossellini as cameraman on some of the earliest nature shorts, is clearly exaggerating when he says that "Commander De Robertis, who for me was a real genius, was the inventor of neo-realism, not Rossellini, who stole everything from him. De Robertis was a genius, a strange man, who felt sympathy for Rossellini and had him do La nave bianca , and then did everything over but allowed Rossellini to get credit for it."[1]

Polemic and score settling run high in the always politically charged arena of Italian cinema, and one despairs of ever attaining the truth. Certain matters are clear, however. For one thing, while Uomini sul fondo is usually praised, De Robertis was unable to repeat its success, and his later films like Alfa Tau and Uomini sul cielo (Men in the Sky) are distinctly inferior. Nevertheless, De Robertis must be given credit for the innovations of Uomini sul fondo , which, while hardly new to Italian film, he managed to put together in a fresh way. The film uses nonprofessional actors and real locations; furthermore, it is generally antispectacular and antiliterary, and even contains some narrative ellipses

that allow the action to be conveyed with maximum efficiency. In addition, the film uses no voice-over and little dialogue, preferring to let the visuals carry most of the meaning. Soon enough, in fact, we realize that the real stars of the film are not the men but the gadgets and gauges we see in profusion before us.

Though it is often said that this film, as opposed to La nave bianca , is solely documentary, purely factual, De Robertis was not above using the conventional techniques of sentimental melodrama. So, for example, shots of the men working in the submarines are often intercut, especially after one of the submarines crashes, with shots of girlfriends waiting for their brave men. The return of one submarine is greeted with joyous shouts from the women, but another melodramatic shot singles out two young women, disappointed in their wait for the submarine that has crashed, as the gates are closed on them. At one point De Robertis even irises out on a cute little dog who also awaits the men's return and irises back in on a matched shot of a dog aboard the submarine. Later one of the two submarines thought lost returns, and the two waiting women—one smiling and the other frowning—are contrasted in an obvious, overstated shot. Even more insistent is the crosscutting that occurs near the end of the film, when all of Italy, through the radio, is involved in the rescue attempt. Cute children pop their heads into familial tableaux around the radio sets, and during one sequence the camera comes to rest on a sleeping baby, perhaps implying his or her unconscious involvement as well. By the end of this sequence, the listeners are shown only as shadows, presumably to heighten the sense of grim foreboding.

Most important is the fact that in spite of the hyperbolic editing that assails us throughout the film, Uomini sul fondo is finally rather uninteresting. The problem is that the shots themselves are often exasperatingly similar, and the final effect is an artificially induced, unconvincing excitement imposed on the editing table rather than arising from the images themselves. The exterior shots, which contain little visual tension and less movement, are especially dull (and sometimes even overexposed and out of focus, giving the impression of incompetence rather than newsreel veracity) and relate poorly to the rest of the film. Thus, if Rossellini did in fact borrow his style and approach directly from De Robertis (and this is debatable), he made great improvements in the process.

What De Robertis originally wanted from Rossellini on La nave bianca , as the title shows, was a short, reassuring film on the efficient and humane care received by wounded sailors on hospital ships before they were sent home. It is unclear why Rossellini was asked to do this, though perhaps De Robertis knew his short nature films or Vittorio Mussolini had put in a good word for him. Apparently, Rossellini had bigger ideas, however, as he related years later: "I began with the idea of making a ten-minute documentary on a hospital ship, but ended up doing something completely different. . . . The film that I tried to make was simply a didactic film on a naval battle. There was no heroism involved because the men were closed up in so many sardine cans and had absolutely no idea what was going on around them."[2] After completing the initial shooting, Rossellini returned with some 50,000 feet of exposed footage, and it was decided, not without some bitterness in various quarters, to pad the film out to feature length by adding a love story, which would also make it more ap-

pealing to a mass audience. (Both Rossellini and De Robertis have denounced this addition, but ironically, it is the love story, though seriously flawed, mawkish, and clearly supportive of Fascist values, that humanizes the film and makes it more appealing.) De Robertis has admitted, "I, not without having asked for forgiveness from my conscience, inflated the short film by cramming into the primitive linearity of the narrative an utterly banal love story between the sailor and the Red Cross girl." Nevertheless, he went on to hint darkly that Rossellini did not really deserve the credit for the film: "The authorship [of this film] conceals a question so delicate as to force on me the duty of leaving the clarification of the case to the correctness and professional loyalty of Signor Roberto Rossellini."[3] Rossellini told interviewers, "Half of the copy of La nave Bianca now in circulation isn't mine. . . . The whole of the naval battle is mine, but the sentimental part was done by De Robertis."[4] What is unclear, yet important, here is whether De Robertis merely wrote the sentimental part of the film or actually filmed it himself. In yet another interview given near the end of his life, Rossellini said, "I was supposed to do a ten-minute documentary on rescue operations in the navy. Once they saw what I had done, a whole operation began: they took the film out of my hands, redubbed it, recut it, changed it, and then took my name off. They then put it back when I became known, after the war. They even had others shoot some of the scenes."[5] The only conclusion to draw out of this welter of claims and counterclaims is that one is on very shaky grounds approaching this film from a purely auteurist point of view. We will probably never know exactly what Rossellini was responsible for, and what was contributed by De Robertis and others, still unnamed.

La nave bianca opens with bold titles that explicitly ratify the realist aesthetic of Uomini sul fondo , while at the same time going beyond it in certainty of purpose, if not clarity of rhetoric:

IN THIS NAVAL STORY, AS IN "UOMINI SUL FONDO," ALL THE CHARACTERS ARE TAKEN FROM REAL LIFE AND FROM TRUE LOCATIONS

AND ARE FOLLOWED THROUGH THE SPONTANEOUS REALISM OF THE EXPRESSIONS AND THE SIMPLE HUMANITY OF THOSE FEELINGS WHICH CONSTITUTE THE IDEOLOGICAL WORLD OF EACH OF US

PARTICIPANTS: THE NURSES OF THE VOLUNTARY CORPS, THE OFFICIALS, THE SUBOFFICIALS, THE TEAMS

THE STORY WAS FILMED ON THE HOSPITAL SHIP "ARNO" AND ON ONE OF OUR BATTLESHIPS.

From the very beginning the urge is to specify, to name, to assure that all this is real —in other words, not what one is used to seeing on the screen. The first shots are focused on the large guns of the battleship, appropriately enough in a film that, like Uomini sul fondo , will be obsessed with the weight and presence of objects. We see the guns from many different angles, all of them dramatic, and all of them reminiscent of the guns in Battleship Potemkin; in fact, Eisenstein, against whom Rossellini has usually been ranged by Bazinian realist theory, is clearly the predominant influence in this film. The effect of this beautifully composed initial sequence is cold and machinelike, but it also signals an interest in formal composition and mise-en-scène that is enhanced by superb

The influence of Eisenstein: Potemkin -like guns fire from the

battleship in La nave bianca (1941).

lighting and rich blacks and whites. The shots seem spontaneous and carefully chosen at the same time. Rossellini, of course, claimed that he never strove to make a shot beautiful but only "true." (In 1947 he even went so far as to say, "I don't like and I have never liked 'beautiful shots.' If I mistakenly make a beautiful shot, I cut it."[6] ) Happily, this false and naive dichotomy, considering the illusionistic basis of all realism, was seldom adhered to by Rossellini in his actual practice. In the first scene, when the individual sailors are presented to us in all their regional and idiosyncratic specificity, Rossellini organizes space by putting the men behind a table, a technique he will employ for the next thirty-five years. The effect of the tables here and elsewhere is to give spatial coherence and visual density to a specific scene. In the opening few minutes, we also see a very Eisenstein-like shot of sailors sleeping in their rhythmically swaying hammocks and an excellent group shot in which the closest men, in shadow, have their backs turned toward the camera, which thus ends up shooting through dark to light, giving a dramatic impression of depth. Other borrowings from Eisenstein's mise-en-scène are the sailors sweeping the deck in rhythmic unison, and perhaps the decision to intercut shots of the cat and dog playing, rather than bringing them into the frame with the men. In spite of such attention to

the composition of the frame, however, this film's shots seem infinitely more spontaneous—and certainly more interesting—than the rigidly planned shots of Uomini sul fondo , whose director expressly avoided any form of improvisation.

Rossellini is obviously fascinated by the sheer presence and authenticity of the many gauges, pieces of equipment, and even doctor's instruments that his camera lingers over. We feel a sharp sense that no studio ever could have invented these things that we are seeing, that we have been transported back to the early days of the cinema, when the Lumières were astounding audiences simply by showing them the real. An excellent sequence occurs in the boiler room, in the bowels of the ship, where the restless camera finally slows down a bit and plays over the multitude of dials and knobs and buttons, and on the real sweat of these convincingly real ethnic faces. What comes to the fore is Rossellini's lifelong interest in capturing a specific time and place—think of all the titles that are so utterly localized in both dimensions, like Europa '51, India '58 , and Germany, Year Zero . Here, Rossellini's formidable powers of observation are especially focused on place: the battleship becomes the star of the film, the center of the universe. The white ship of the title, in fact, is actually a misnomer, since it does not even appear until part 2, when the film has lost most of its energy and much of its interest.

In his later remarks Rossellini has, not surprisingly, stressed what might be called the humanistic themes he sees in the work. He told François Truffaut and Eric Rohmer in 1954 that the same moral position evident in Open City was already present in La nave bianca:

Do you know what it's like on a battleship? It's horrible: the ship must be saved at all costs. There are these little guys there who don't know anything, guys recruited out in the country, trained to run machines they don't understand: they only know that a red light means to press a button and a green light means to push a lever. That's all. They're locked up this way, nailed into their sections . . . sometimes even the ventilation is cut off so that the gas from explosions won't spread through the ship. . . . They don't know anything; they just have to watch the red and green lights. From time to time a loudspeaker says something about the Fatherland and then everything falls back into silence.[7]

One cannot doubt Rossellini's sincerity here, but it must also be admitted that the film itself only partially supports his view of its theme. Rather, the overriding impression is not of the brutish oppression of these men—no matter what was intended—but of Rossellini's terrific fascination with the workings of things. One is in fact more likely to be struck by the appositeness of one of the Duce's slogans that happens to be caught by the camera eye: "Men and machines: a single heartbeat." What emerges in the film is the Hawksian thrill of men working together, supremely competent, in a dangerous collective enterprise; their frenzied activity ultimately becomes that of a machine, an effect heightened by the crisp precision of the editing and camera movement.

The coralità theme of Rossellini's early career also emerges in the men's collective activity. As he told Mario Verdone in 1952, "La nave bianca is an example of a 'choral' film: from the first scene, in which the sailors write to their

pen pals, to the battle and the wounded who attend Mass or who sing and play music."[8] There are no stars in this film other than the ship itself, no individuals whose fate seems to be privileged. The needs of the collectivity are favored over the individual ego, yet the men are not reduced to heroic automatons, empty symbols for the masses, as they sometimes are in Soviet films, nor faceless cogs, as they are in Uomini sul fondo . Instead, Rossellini humanizes them with small details that give us a glimpse of their individual personalities, without, of course, actually making them fully rounded characters. For example, in perhaps the most powerful sequence of the film—the loading and firing of the big guns—we see how frightened the sailors are, though, characteristically, Rossellini understates. The greatest humanization of the film's material by far, however, is effected later through the much-maligned love story, in which one sailor's pen pal turns up as a nurse on the hospital ship. The lovers have earlier exchanged halves of a heart locket, and when she sees his half hanging from a chain around his neck, she recognizes the sailor but he does not recognize her. Duty, however, forbids her from favoring him over the others, or from even revealing her identity. Though mired in the mindless sentimentality that the rest of the film tries to transcend, the love story at least serves to make the men flesh and blood, and acts as a saving, if somewhat labored, counterpoint to the cold efficiency of the machines.

By the end of part 1, the sharp blacks and whites have been replaced by mist and smoke, as the ship, like the men, has been gravely wounded; disorder and human vulnerability have spread to the lifeless world of the machine. A peaceful calm reigns over all, as though, the battle over, some primal order has been reestablished, as at the end of Fantasia sottomarina . The overall rhythm of part 1—stasis, chaos, stasis (another nod to Eisenstein)—is marked and satisfying; the images themselves finally resolve into a complex, circular whole with the reappearance of the guns with which the film began.

It is true, as most critics have felt, that part 2 of the film is much less vibrant than part 1. Whereas in part 1 the love story lightened the material and humanized the characters, here its ubiquity is a serious drag on the film's innovative energy.[9] But it is also true that the slowness of the second part of the film is a function of the attempt to document life aboard the hospital ship this time, where the action will, naturally, be radically slowed down. The aim is to build carefully, to create a mood and a fuller sense of a specific reality through the accretion of small details, purposefully avoiding high drama and fast cutting. Here we can see the first inconsistent glimmerings of what will soon become Rossellini's celebrated—and, to many, alienating—techniques of dedramatization and an undirected narrative that allows for the inclusion of the aleatory and the irrelevant.

The ending of the film is cinematically interesting and thematically problematic. In the final scene Rossellini treats us to a complex montage taken directly from Eisenstein: the camera cuts quickly from one wounded sailor to another as they hear a passing ship (they are anxiously awaiting news of their mother ship), and the effect is repetitive and yet cumulative at the same time. In other words, the cuts are matched (each sailor is seen from the same angle and distance, making the same head-turning gesture), but since the action is slightly

advanced with each shot, the result is to stress their camaraderie and coralità and to lengthen the moment artifically, in Eisenstein's manner, in order to underline the event and its attendant emotion.

Again, as in part 1, the newly returned ship occupies our attention: the men who can walk hobble out onto the deck to see the ship passing. They stand at attention, though with none of the Fascist salutes seen earlier in the film, and the general feeling is strongly patriotic. Basso, the closest the film has to a protagonist, watches with his Red Cross girlfriend through the porthole, and though she has yet to reveal her true identity, we sense that she will do so soon. At the very end, the love story is revealed for the vehicle it is, for the emphasis is clearly on the ship and the feeling the men have toward it, a relationship perhaps more emotionally complex, one senses, than they could ever have with a woman.

Critics have disagreed about the Fascist elements of the film. The ending is certainly patriotic, but it is difficult to put a more specifically "Fascist" interpretation on it (Mussolini's government was hardly the first to extol the virtue of duty to one's country and the comradeship of men at war). At one point during the middle of the film, we are shown a meeting room adorned with portraits of the king and Mussolini, but again, this seems to serve a documentary, rather than rhetorical, purpose. Some anti-Rossellini critics have even spoken of a nonexistent shot near the end that focuses approvingly on the Fascist insignia, but this is clearly a mistake, or worse.[10] On the other hand, critics like Massimo Mida, who has said that this film and Un pilota ritorna represent "the first break at the very heart of official Fascist cinema," are surely exaggerating.

More interesting are the charges brought by the Italian feminist Maria-Antonietta Macciocchi who, in her important study Les Femmes et leurs maîtres , refers in passing to La nave bianca as a "film-text of pure-mystical-repressive fascism, which confirms that mysticism favors sexual repression, and consumes sexual energy."[11] Actually, her critique here applies rather more forcefully to the films Rossellini made ten years later with Ingrid Bergman, as we shall see, which often do end in a kind of mystical haze not unrelated to sexuality. Macciocchi more closely describes the particular sexual dynamics of La nave bianca in her excellent little book on the role of women during the Fascist period entitled La donna "nera." Though I think she oversimplifies Rossellini's relation to technology in this film, and his reasons for not showing the enemy, she is right that the film manifests the quintessential Fascist view of woman as producer of heroes, or failing that, a nurse or a schoolteacher. (The woman in La nave bianca is a nurse and formerly was a schoolteacher.) Women are only meant to take care of men and, as Macciocchi points out, the madrina (godmother) of the film, as she is called, gives constant encouragement to her sailor boy and, in her last letter, writes: "In war, there is only one feeling: duty." Further, says Macciocchi, "The man-woman relationship is presented in a light that is purely protective and maternal." When the madrina helps the wounded sailor sign a letter, she has a flashback (the only one in the film) to the students' hands she held while teaching them to write. Since she never played favorites among her students, she cannot now give special treatment to one of the

wounded, even if she is in love with him. "Here we find the equation man = son, and woman = mother = teacher, key to the Fascist ideology of the woman." It is particularly appropriate, Macciocchi believes, that the madrina does not reveal herself to the sailor even after he has seen her half of the heart locket, nor does she respond when he calls her name. At the very end they lean toward each other, but do not kiss: "Chaste love, purity, the abnegation of the woman for the wounded, exhortation to patriotism, all these clichés of Fascist ideology find their consecration in the film's ending."[12] Macciocchi's analysis is provocative, but it remains unclear whether the depiction she accurately describes is really Fascist or merely an extension of already prevailing attitudes toward women in Italian culture.

When the film first appeared, critics were sensitive to the fact that something a bit different, at least in its mode if not in its ideology, was going on here; in many cases, in fact, they seemed more aware of the film's possibilities than did its makers. Pietro Bianchi, for example, writing under the nom de plume Volpone, in Bertoldo , a leading intellectual journal of the time, complained, "It seems they were afraid of the masterpiece that was about to be born, far from the sentimental equivocations of the petty bourgeois mentality, and unfortunately, they stopped just in time." (He concludes, however, with the more typical Fascist notion that "recently, we have rarely been treated to such a high vision of military duty and of the manly confrontation of the combatants of the sea with dark destiny and unlovely death".)[13] More palatable is the view of Adolfo Franci, writing in October 1941, the first to speak of Rossellini's characteristic search for the "essence" of reality, rather than simply presenting what happened to be in front of his camera. This notion, as we shall see, will reappear in many different contexts through the ensuing forty years of Rossellini criticism. Here, Franci does not belabor the point, but merely mentions the battle scene in which the director "shows an extraordinary capacity for getting to the essence of such a description, which he conveys successfully with an urgent and precise rhythm, to a very beautiful cinematic effect."[14]

3—

Un Pilota Ritorna

(1942)

Un pilota ritorna (A Pilot Returns) represents Rossellini's look at the second branch of the Italian armed forces, the air force; the army will provide the background for his next film, L'uomo dalla croce . Never mind inclined to discuss this film with interviewers, the director often grew quite testy with those who pursued the subject. Perhaps this is because the film was thought lost for nearly forty years, and since none of his interviewers had seen it, he may have thought that the less information he provided about another compromising film, the better. Un pilota retorna resurfaced, finally, in 1978.

One major reason Rossellini would not be proud of the film is that the subject came from Vittorio Mussolini (again under the anagrammatic pseudonym Tito Silvio Mursino), who acted as the film's supervisor, and who claims that he got Rossellini the job of directing. According to Mussolini, the film was quite baldly meant to "make known the heroism of our air force."[1] Massimo Girotti, who played the lead, later said that he considered it a patriotic film, though not propagandistic, even if the son of Mussolini was involved: "It was a dramatic film like any other, though with a heroic-patriotic background, of course."[2] The film's opening titles, however, are more direct. The first one states that "this film is dedicated with a fraternal heart to the pilots who did not return from the skies of Greece"; the second informs us that the film was made under the auspices of the "General Command of Fascist Italian Youth [Gioventù italiana del Littorio]." Like La nave bianca , in other words, it is not exactly propaganda, but it clearly propounds the official values of the regime. In one of his rare comments on the film, Rossellini told Francesco Savio in 1974 that he did not want to talk about it:

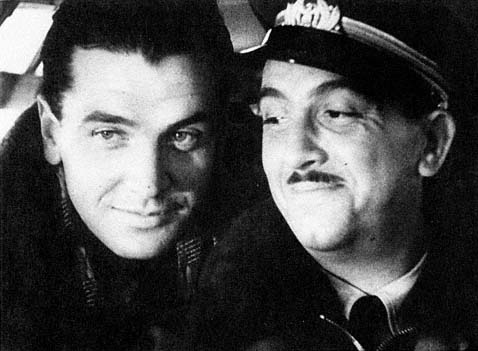

Men at war: Lieutenant Rossati (Massimo Girotti, left) and

fellow pilot in Un pilota ritorna (1942).

Courtesy of Intercinematografica.

Today it's becoming extremely disagreeable to talk about these things because it has become so much a way to proclaim yourself a victim of political pressure, which is also boring. I can say that certainly all the dialogue of Un pilota ritorna was changed. All of it.

Q: With regard to the original subject?

A: Yes.

Q: Which was by Vittorio Mussolini.

A: Well, it was just an idea. I always maintained complete freedom, and never started with little scraps of writing.[3]

At the beginning of this exchange, Rossellini hints at some form of political struggle over the film that he is too large-minded to excuse himself with. By the end, however, he seems merely to be referring to his lifelong practice of refusing to write out completed scripts before beginning production.[4] Though it is difficult to give credence to Rossellini's claim that all the dialogue has been changed, responsibility for the film remains uncertain.

The plot of Un pilota ritorna is slight and undistinguished, allowing the director to concentrate his attention elsewhere. (Interestingly, the young Antonioni also worked on the screenplay.) The action takes place in Italy and Greece in the early spring of 1941. The first part shows the Italian air force to great advantage, as it relentlessly attacks the Greek enemy. A young pilot

arrives in camp and becomes part of a squadron of older, more experienced men, and we are shown scenes of camaraderie that do little to advance the narrative. During an air battle, the young pilot's plane is hit, and he and his comrades must parachute to save themselves. They are captured, and the rest of the film shows them as prisoners of war, first of the British and later of the Greeks. In one of the camps, an Italian officer, gravely wounded in the leg, is operated on by an Italian doctor who just happens to be there along with his seventeen-year-old daughter. The young pilot, as might be expected, falls in love with the daughter. During an aerial bombardment, he manages to steal a plane and fly back to his home camp in Italy; from the air he sees the various landscapes of his country in a highly lyrical passage and, though under fire from his compatriots, manages to land safely, just in time to hear the news of Greece's surrender.

One major difference between this film and La nave bianca is that, while the documentary element is still very much in evidence, the fictional human interest aspect is stronger as well and more closely integrated into the whole. The attempt at a psychological portrait, however tentative, is obviously the most important change here, and one suspects that the inclusion of a talented star (Massimo Girotti, who played the lead in Visconti's Ossessione the same year) had something to do with this. Yet in spite of the increased psychological realism, Rossellini shows his willingness to oppose conventional filmmaking practice by refusing, at least in the first part of the film, to focus unduly on Girotti. Coralità is more important to the director at this stage of his career and thus we see the pilot as part of a group; only when the love interest becomes dominant is he emphasized as an individual.

Thematically noteworthy are the scene in which the pilots scoff at accounts of "heroism" in the newspapers and the overwhelming images of forlorn refugees that dominate the last half of the film. Little glory is associated with combat, and Rossellini's later, more fully developed theme of war as destructive of all human relationships is more than hinted at here. The pilot at times seems pleased about the Italian advance and at other times displeased. The final shot of the film is a close-up of his face after he has safely landed; all around him his fellow aviators are celebrating his return, but his expression is more enigmatic, a combination of relief and unease about the girl he left behind. In spite of its glorification of military life, in other words, the film also raises doubts about Fascist rhetoric. Furthermore, the pilot's captors are generally seen to be civilized and decent, ready to break the rules of the camp for a humanitarian reason. (With the sole exception of the Germans in Open City and Paisan , Rossellini will continue throughout his career to insist upon the humanity of the enemy.) Yet, later in the film, the British leaders seem completely undismayed about the prospect of making "a desert in front of the enemy." This, by the way, is said in English (and the Greeks speak Greek, sometimes at length), thus initiating an ongoing, rigorous allegiance to authenticity of language that will baffle many an Italian audience and even be complexly thematized in Paisan .

Un pilota ritorna is perhaps most interesting in terms of technique, which tends to mitigate its conventional melodramatic elements (such as the leg am-

putation scene with cognac as the only anesthetic). The controlled studio lighting makes it seem much more polished than Rossellini's later films, but the director seems to be striving for visual unconventionality as well. The editing, for example, looks forward to later experiments, for much of it is elliptical to the point of incomprehensibility. Similarly, a remarkable shot early in the film shows the pilots emerging from a theater; for an exceptionally long time all we see is a small bit of light through the curtain leading to the auditorium. A lengthy bit of dialogue goes on in almost complete darkness, and then finally several characters light cigarettes, illuminating themselves in the process. Even more daring is the 360-degree pan around the interior of the farm building in which the pilot, the girl, and the wounded prisoners have taken refuge. The pan begins with the girl reading aloud to solace the prisoner whose leg has been amputated, but by the time the pan comes back to her, we understand it as a kind of dissolve, and she is asleep. A world-weary sense of the destructiveness of war is the result.

Equally innovative, and characteristically Rossellinian, is the relative lack of interest in a strong narrative thrust. Thus, when the pilots take off on a bombing raid, a remarkably long time is devoted to the minutiae of their occupation and environment (altimeters, oxygen masks, and so on) before the battle begins. Later, they ride bicycles around the camp for no apparent narrative purpose; clearly, Rossellini is intent on giving us a picture of the pilots' everyday lives that refuses to be subsumed into the merely dramatic. Furthermore, emotion is drastically understated, as when a crew member indicates to the protagonist, by the slightest nod of his head, that the pilot of the airplane has been killed. The real drama, we come to understand early on, concerns the overall war effort, the large movements of armies, rather than the plight of specific individuals.

By far the most important, and most symptomatic, contemporary review of the film was written by Giuseppe De Santis for Cinema when the film first appeared in April 1942. Despite De Santis' obvious desire for something new, something "real," his model is still the illusionistic, dramatic, and psychologizing Hollywood style of filmmaking that, above all, follows a conventional narrative pattern. At the close of his review, he complains:

Each sequence of Pilota overlaps the next, neither one of them properly expressed because neither is concluded. What is the meaning of the pilots' visit, at the beginning of the film, to the girls of the city, if in the story the courage isn't there to get into its motives? What is the poetic necessity of that descriptive pan of the prisoners' shelter, when the girl reads something aloud after the operation? . . . What environmental coloring did Rossellini want to add when he has the aviators ride around the camp on bicycles during a break? If he meant to show us a documentary episode on military life, the episode itself should have told us something we didn't already know, in a narrative and psychological progression.[5]

Evident here is the demand for authenticity, the longing for the real thing—but a reality artfully arranged in a coherent, conventional narrative form—that was beginning to stir in Italian cinematic culture. Naturally, it was never

asked whether this narrative form itself was "true" and "real." For De Santis, each scene must have a meaning or point, an express purpose that furthers the plot line or the psychological portrait of the characters. No latitude is allowed for the aleatory or the "irrelevant," elements whose significance might transcend that of conventional narrative. To ask what is the "poetic necessity" behind this shot or that shot is to assume that every shot must contribute to an overall organic project, where every element works not for itself, but is subsumed into the whole.

But Rossellini was already thinking of alternatives to this model. Less than a year later, in fact, after having been forced to abandon his next project, Rossellini was discouraged about his prospects as a filmmaker and went to see the novelist R. M. DeAngelis. Out of work, he confessed to DeAngelis that, even though he did not know much about narrative technique, he wanted to become a novelist because he despaired of ever finding the wherewithal to make another film. But Rossellini was not satisfied with DeAngelis' definition of the novel and its possibilities, and realized that for him it would have to be the cinema or nothing. His reply to DeAngelis is important for understanding what he was trying to do at this early stage of his career:

I need a depth of field which perhaps only the cinema can give, and to see people and things from every side, and to be able to use the "cut" and the ellipsis, the dissolve and the interior monologue. Not, of course, that of Joyce, but rather that of Dos Passos. To take and to leave, inserting that which is around the fact or event and which is perhaps its remote origin. I can adapt the camera to my talents and the character will be pursued and haunted by it: contemporary anxiety derives precisely from this inability to escape the implacable eye of the lens.[6]

For the next forty years, in fact, Rossellini was to be faulted for not meeting the demands of a conventional narrative form whose own validity and "naturalness" would seldom be questioned. Though they overstate their case, especially for these early films, Aprà and Pistagnesi are right to insist:

What is so striking in the first three films, beyond their quality, which is actually quite modest, is that Rossellini has left behind the "strong" models of the classic cinema, that is, the propaganda films and the two examples of Luciano Serra, pilota and Uomini sul fondo . . . . In respect to these two models he makes a work of deconstruction, of disassembly , taking out of them the elements which make them "classic" films. For example, [Rossellini's] films, even though they tend toward narrative, are told "badly," with ellipses which often make the events obscure, or better, "incomplete." . . . Rossellini will often be accused of not knowing how to tell a story, but what is not noticed is that Rossellini wants to tell the story badly, because he is not interested in the plots but in the pauses, the moments of rest, the waiting, or certain contrasts between characters or between characters and the background, which manifest themselves only on the screen, not in the plot.[7]

This point of view is one I most emphatically share concerning the later films, including perhaps Paisan , but especially those made during the Ingrid Berg-

man era. For one thing, this penchant for narrating "badly" helps us to understand why Rossellini's films have always fared so poorly at the box office. The antinarrative elements of films like Un pilota ritorna , however, are only barely in evidence; Rossellini himself can hardly be said to be fully aware of them, or actively seeking to alter conventional techniques of cinematic narration. But they are there, seeds barely sprouted, of a new way of making films.

4—

L'Uomo dalla Croce

(1943)

Rossellini's next film, L'uomo dalla croce (The Man of the Cross, 1943), completes his trilogy on the armed forces. The integrity of this film has not been tarnished, for once, by an association with Vittorio Mussolini; unfortunately, however, his place as screenwriter has been taken by the Fascist ideologue Asvero Gravelli, a journalist well known for his nightly radio commentaries supporting the government and for his work as editorial chief of Fascist Youth and Antieuropa . It is also true that this film is even more overtly ideological than the two earlier films of the trilogy, but again, its ideology is more complicated than some have made it out to be. Not coincidentally, it is also more heavily weighted toward the fictional and away from the documentary, and actually is the most melodramatic of all the pre–Open City films.

The man of the cross referred to in the title was based on a real army chaplain, Father Reginaldo Giuliani, who had been recently killed on the Russian front. In this, the film resembles Open City , whose main character was also to be based on a real-life priest. The plot, which centers around a small Russian village, is surprisingly simple. In the beginning Rossellini presents his Italian soldiers with all the "reality" he can muster as they wait for their friends to return from a tank attack. When they do return, one of the men is found to be so seriously wounded that he cannot be moved; the chaplain, who is also a doctor, resolves to stay with the man even though the Russian troops are advancing. (The chaplain, despite the heavily "acted," rhetorical nature of his role, is played by a nonprofessional who was an architect friend of Rossellini's.) The next day the village is captured by the Communist forces, the priest is interrogated, and a young Italian soldier is executed because a Fascist party

membership card has been found on his person. The Italians counterattack, and the village finds itself caught between the opposing armies. During the course of the night, a motley assortment of Italian soldiers, Russian peasants, children and dogs, committed Communist commissars, and the priest ends up seeking shelter in the same small farm building, or izba . The priest teaches the children to make the sign of the cross, delivers and baptizes a baby, and brings the word of God to a young Communist woman whose lover, Sergei the commisar, is killed during the night by another Russian. The next morning the priest himself is mortally wounded while attempting to save the life of the man who killed Sergei, having first taught this man to say the Our Father. Just as the chaplain dies, the Italian forces recapture the village.

Like the two previous films, L'uomo dalla croce is divided between a real documentary interest in the daily activities of the Italian soldier and a thoroughly conventional melodramatic intensification of danger, suffering, and psychological drama. Even the hoary stage device of having all sorts of different characters seek refuge in the same location was, at least in American films, a cliché by 1943. The music, by Renzo Rossellini, is equally melodramatic and is in fact strikingly similar to that of Open City , Rossellini's next completed film. In spite of all this, however, as a war picture, L'uomo dalla croce is impressive. It was singled out by critics at the time for its realistic battle scenes, which of course are altogether different from the documentary realism of the soldiers' everyday lives, the subject perhaps most interesting to Rossellini. The battle scenes are "realistic" mostly because they are what an audience raised on American films would expect and demand, but this is not the same kind of reality Rossellini is after when he lovingly and lengthily concentrates on the details of the tanks in close-ups, or later, on the horrifying, but visually magnificent, flamethrowers to which we are treated to relieve the boredom of the plodding tanks. This distinction between realism and reality is in fact a crucial one, and will be examined in greater detail in a later chapter.

The same kind of critical misunderstanding that we saw earlier in regard to Un pilota ritorna reappears, and again it centers on a review by Giuseppe De Santis in Cinema . De Santis speaks glowingly of the battle scenes, whose "authenticity is worthy of the best shots of LUCE [the government agency responsible for informational films]," but he complains that the rest of the drama is conducted slowly and "inflated with empty places and unfillable pauses." He is right, of course, to critique the film's clichéd content and most of the dramatic scenes in the izba for their employment of "terminology already used by cheap novels." But he is less sensitive to Rossellini's hesitant steps to go beyond what might be considered clichéd narrative form. De Santis' key word, which stands in for "conventional narrative and dramatic form," is rhythm . Thus, Rossellini's attempt to reflect the minor events of a given reality is regarded as an error because it is not rhythmic, that is, it does not contribute to the onward rush of the narrative. Hence, De Santis is in favor of the "drama of waiting" not for the sake of the waiting itself, and the creative temps mort that Rossellini is just beginning to explore in these films, but for the suspense of the drama, the end point, the product rather than the process: will our comrades return or not? He is clearly bothered by Rossellini's dilatoriness ("The

camera carries out its movements lingering slowly, describing: a bird perched on the branches of a tree, a shirtless soldier stretched on the ground, others who tell each other their life stories, remembering their studies or their homes") because nothing seems to be happening. He also finds the little scenes with the peasants, which do not clearly advance the narrative, banal and extraneous because they offer "psychological reactions which don't fit with the drama of waiting."[1]

A more modern and more appreciative view of Rossellini's particular gifts (which benefits, of course, from a hindsight unavailable to De Santis in 1943) is offered instead by Gianni Rondolino. He feels that, in spite of the banality of the story, "once again, Rossellini reveals himself in the little things, not in the cut of the narrative or in the psychological penetration of the characters or in spectacular high points, but in the moments of quiet, of waiting, of simple observation of men's behavior in a given situation."[2]

Similarly, Pio Baldelli, one of the director's harshest but most intelligent critics, points out that, in spite of all its faults,

within this opaque material twists a nonrhetorical vein which is a prelude to Rossellini's expressive growth. An antiheroic, antimonumental manner of cutting across certain facts emerges (the reverse of a bourgeois populism), which is uninvolved in military glory and pomp: in other words, the inclination of the camera for the little guy, for the fate of the humble, the victims, the wounded and dead of war. It's the documentary immediacy, when the frame gathers up real objects, discovering the men amid the factual reality; here the long take discovers the surroundings, without emphasis.[3]

Despite the above, however, it must not be forgotten that what might be called the antinarrative elements of L'uomo dalla croce remain thoroughly dominated by the conventional story, filled as it is with clichés of the action genre: the wounded man who cannot be moved, faced with the advance of the enemy; the selfless hero who decides to stay with him; the children and dogs who are nearly killed when they wander out of the izba; the pregnant woman who gives birth just then , in the middle of the night, stuck between rival armies; the grieving woman who draws renewed hope from the birth of another's child; the wounded soldier who asks to be propped up to look at the stars; the hero who gives up his life, ironically, at the very moment of his countrymen's victory. And so on.[4]

In terms of its visual style, the film is somewhat more complex than its predecessors. In general the camera is fluidly mobile, and, appropriately perhaps for a war movie, its intense activity matches the film's frenetic editing. Nor does Rossellini avoid the self-conscious, artfully composed shot now and then, though such shots are much less evident than in La nave bianca .[5] Under the prodding of a student interviewer, Rossellini much later spoke cryptically of the "rhetoric of the long take" of this film,[6] but his memory of past practice seems to have been colored by what he was doing at the time of the interview. L'uomo dalla croce does contain some relatively long takes—especially, of course, in the "documentary" sequences of the passing tanks and the flamethrowers—but not more than in any American action film of the time, and they are a great

The group, in the protected inner space: the man of the cross (Alberto Tavazzi)

ministers to the wounded in L'uomo dalla croce (1943).

deal shorter than those of Rossellini's later films (for example, the eleven-minute shot in Blaise Pascal ).

The film's visual images also have a clear, if subtle, thematic resonance. For example, the men in the opening sequences are striking in their very ordinariness and their evident, if unspoken, sense of helplessness. They are all so incredibly small and unimpressive—some without shirts, some in shorts—a far cry from both the Nazi superman and the Fascist bringer of civilization to the expanding Italian empire. Rather, they seem frail and worried, and no Sergeant John Wayne arrives to buck up their spirits and make men of them. In fact, the priest's heroism in this film is clearly not meant to inspire the others to feats of courage; it is, finally, a lonely act, simply an accomplishment of what he sees as his duty. Despite the priest's solitary act of courage, the thematic center of the film seems to reside in the collective, communal spirit of coralità . Hence the importance of the idea of return in all these early efforts: the wounded sailors of La nave bianca anxiously await the return of their battleship from its dangerous mission; the pilot's struggle in the next film is aimed at the fulfillment of its title, his return to Italy; and finally, in L'uomo dalla croce , whose entire first part is devoted to the common soldiers' longing for the return of the tanks, and thus their friends, to the group. Though the film's intense cutting, as in La nave bianca , forces us to see the men as separate indi-

viduals, each one caught in his own frame, the men are anonymous, and thus blend more easily; the additive or cumulative nature of montage also results ultimately in a collective effect. Additionally, in at least one sequence the cutting from soldier to soldier is the same as the Eisensteinian progressive sequence we saw at the end of La nave bianca . Because each soldier the film cuts to is matched with all the other shots in this sequence, the effect is paradoxically one of togetherness arising from separateness, collective identity transcending individual identity. Totally absent is the Hollywood technique of humanizing war movies by following the course of a battle in the specific terms of a small group we have come to know, in order to allow for the maximum psychologization of the characters. In L'uomo dalla croce , when we do follow troop movements or witness battle scenes, we see men acting together, unheroically and anonymously.

Coralità is even more evident during the agonizing night spent in the izba . There, a Renoirean theme of the artificiality of national boundaries develops, and in this coveted inner space of protective warmth, in spite of occasional conflicts, a structural opposition to the war outside is established. Thus, at one point, a baby wanders out into the night and immediately machine guns begin to chatter; the line between the outside and the inside is exceedingly thin and in fact will break, if not then, the morning after. The inner space is also sacred for Rossellini because it is here that one's personal salvation must be worked out—in the context of the group, certainly, for it is there that we realize our common humanity and find the aid and comfort that we seek, but in the final account, one is alone, face-to-face with God. This theme is embodied most directly in the encounter between the chaplain and the disillusioned Communist woman he comforts. She is utterly bereft in the wake of her lover's death, and the priest tells her that she cannot be reborn because she has no hope. God is waiting to save us all, and instead of thinking about the dead Sergei, she should think of Jesus Christ, who gave his life so that everyone, including she and Sergei, might live. The priest finally asks the woman to consider the baby who has been born during the same night her lover was killed (and whose crying we hear on the sound track). As the woman thinks of this new life, a smile comes over her face, and, having become hopeful once again, she presumably is saved.

The point here is heavy-handed, to be sure, and even rather embarrassing to a secular audience, but it is significant in terms of Rossellini's later development. Most critics, who have begun to study Rossellini's career with Open City , rarely considering the earlier trilogy, have lavishly praised the dominant "choral" elements of that film and Paisan , films in which the individual's search for salvation is lost amid the epic sweep of history at its most eventful. Then, with Germany, Year Zero, The Miracle , and especially the Bergman-era films, Rossellini was accused of betraying neorealism and coralità in favor of the petty concerns of the individual. The truth, seen clearly in L'uomo dalla croce , is that for Rossellini there has always been something more important than politics and mere physical survival, and that without the spiritual, a human being is nothing. Furthermore, this spiritual salvation cannot be reached by the group, for it is achievable only in the private realm of the self. Thus, the character who

outraged so many critics in 1950—Karin, the seeker of God and spiritual awakening in Stromboli —finds her precursor in the lonely and desperate Russian woman of L'uomo dalla croce . For Rossellini, both women are lost souls because they have been following either the false god of communism or the materialist, confused ethos of the postwar world that has made Karin so cynical and manipulative. Both turn to a priest for aid, and the Communist woman, obviously a less sophisticated artistic creation, is easily solaced (after all, Rossellini still has an action war story to tell—even if "badly"), while Karin cynically tries to manipulate her priest, even sexually, for she has not yet understood what she is looking for. Both obtain their salvation by first achieving hope through the intermediary of a baby (the sexist nature of this male vision of what fulfills a woman is clear)—the Russian when she contemplates the newborn of another, and Karin when she finally realizes the meaning of the new life within her. As Rossellini told Eric Rohmer and François Truffaut in 1954, L'uomo dalla croce "poses the same problem [as La nave bianca ]: men with hope, men without hope. It's pretty naive, but that was the problem."[7]