14—

Europa '51

(1952)

Rossellini's next film, Europa '51 , his second with Bergman, has been seen only rarely in the United States or elsewhere since its initial release in 1952. It is not a film that reveals its depths on a first viewing, and, in that regard, is similar to Rossellini's Bergman-era masterpiece Voyage to Italy . It does, however, have its excellent moments. The placidity of Francesco is now absent, for here the director returns to the moral discontinuities of the postwar era. Francesco 's themes are still in evidence, however, now transposed to the modern world, and if the saint's "perfect joy" eludes Irene, the heroine of Europa '51 , her "madness" is clearly a contemporary variety of the strange behavior of those marginalized figures of the Middle Ages. Bergman, in fact, reported that Rossellini told her, immediately after making Francesco , "I am going to make a story about St. Francis and she's going to be a woman and it's going to be you."[1]

The plot concerns a young society woman who is more devoted to giving parties than to her young son. Early in the film, he attempts suicide—recalling the earlier child suicide of Germany, Year Zero —and, after a short period when he seems to improve, dies suddenly of a blood clot. Irene, enormously upset by her son's death, casts aside her former life and, on the advice of Andrea, a cousin who is a Communist journalist, begins devoting herself to the poor. She becomes so intensely involved in her charity work that she is finally committed to an insane asylum, for in her quest for a truly moral life in the service of others, she is judged to be abnormal by all the representatives of society, including her rich husband, the psychiatrist, and even the priest and the Communist cousin.

Again, the characteristic Rossellinian refusal to be judgmental is in evidence. So, for example, while we realize that Irene and her husband have been remiss in not paying more attention to their son, it is difficult to estimate just how much blame we can attach to them. It is always possible that the child is hypersensitive and would have attempted suicide in any case: we simply don't know. Similarly, at the end, though most evidence leads us to suppose that Irene is not really insane, at the same time her behavior is truly "abnormal," that is, not like other people's behavior. What other definition of mental illness do we finally have? Some of the dialogue also perversely goes counter to the rest of the information we are receiving. Thus, when Irene is asked by the priest at the end if she has performed all of her eccentric good deeds out of love, she says no, it was out of hatred for herself and what she was. The line carries just enough manic charge to suggest that perhaps she is mentally unbalanced after all. Despite these ambiguities, however, the characteristic and central ambivalence of the other Bergman films, the man-woman relationship, is here not as sharply etched. Rather, it is Irene's moral struggle that occupies center stage, and the marital relationship is barely portrayed at all. George, her husband, is firmly on the side of the establishment, but is in no sense involved personally with her in an emotional or sexual struggle, as are Bergman's other "husbands."

Other influences besides Francesco were involved in the choice of subject, including Simone Weil, the French social philosopher, mystic, and Resistance fighter who died of starvation in England during the war after renouncing food in solidarity with her countrymen still under the Nazi yoke. One of the most brilliant sequences of the film, when Irene goes to work in a factory one day to fill in for one of her poor friends, seems to have been inspired by Weil's account of the year she spent in the mid-thirties working in an automobile factory, a book published much later in English as The Need for Roots . Since one of the principal areas of disagreement concerning this film has centered on its depiction of Irene's experience in the factory, I want to return to it later.[2]

In formal terms the film is more linear and conventionally "dramatic" than Francesco , probably due to the exigencies of the star system, but it nevertheless remains highly elliptical and the implausible plot development is halting at best. As with the earlier film, these features can be seen as formal manifestations of the shared thematic emphasis on the nonlinear and the irrational. The early scenes laconically portray the domestic life of the Girard family, with little or no time wasted on establishing narrative suspense or on the development of subsidiary characters. Jose Guarner has characterized the film as merely a "statement of the facts," and maintains that the conflict is sketched in Irene's face (close-ups of which obsessively punctuate the film at regular intervals), which he sees giving the film its coherence, similar to Falconetti's face in Dreyer's La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc .[3] Maurizio Ponzi, unconsciously suggesting the complex interplay between the stylized and "real" that we considered earlier in Una voce umana , has in fact called it a "documentary on a face."[4]

Europa '51 can perhaps be best understood as a film à thèse . Rossellini has discussed his intentions in this film in virtually the same terms that he had used earlier concerning La macchina ammazzacattivi . The remarks are important enough to quote in full:

In each of us there's the jester side and its opposite; there is the tendency towards concreteness and the tendency towards fantasy. Today there is a tendency to suppress the second quite brutally. The world is more and more divided in two, between those who want to kill fantasy and those who want to save it, those who want to die and those who want to live. This is the problem I confront in Europa '51 . There is a danger of forgetting the second tendency, the tendency towards fantasy, and killing every feeling of humanity left in us, creating robot man, who must think in only one way, the concrete way. In Europa '51 this inhuman threat is openly and violently denounced. I wanted to state my own opinion quite frankly, in my own interest and in my children's. That was the aim of this latest film.[5]

Rossellini made this statement in the early fifties (note the hint of cold war rhetoric), and his next mention of the film, some twenty years later, is disparaging. By the seventies, of course, his view of the relative merits of the "concrete" and the "fantastic" was quite different, and his emphasis had shifted dramatically to science as the most productive link between the rational mind and the facticity of the world. But, in Europa '51 , rationality is still the enemy because it is associated with the antihuman and the mechanical, those forces that seek to reduce the complexity of the world and human beings to a formula. Whether that formula is scientific, religious, legal, or political makes no difference at all.[6]

Just as we have seen in the films following Open City , Rossellini is operating a complex, dynamic relationship between what might be called the realistic and the expressionist in Europa '51 . In the earlier films, this dynamic took the form of an implied critique, by means of various self-reflexive gestures, of realist aesthetics. Here, what is being questioned is film's ability to penetrate into the "heart" of a character it chooses to study. Still committed to the "documentary of the individual," which came to the fore with Germany, Year Zero , Rossellini seems increasingly dubious about the efficacy of film to penetrate much beyond the surface of raw human phenomena. On one level, then, the film seems to say that it can finally be little more than a "documentary of the face" after all. Irene's character has been interpreted by critics in so many different ways that the final unknowability of the other can even be seen as one of the film's principal themes. Near the end, when she is being "scientifically" tested for mental illness, the flickering tachistoscope that is foisted on her, so closely resembling a film projector, suggests a homology between science and the cinema in the futility of their mutual attempts to penetrate to a sure knowledge of any human being.

Perhaps the film's most obvious theme arises as early as its title: Europa '51 . At first glance, this seems to attest strongly to Rossellini's close attention to "reality." He is not just telling any old story, in other words, but a story that is expressly marked by a specific time and place. Paradoxically, however, Rossellini's title, by its very specificity names a general essence: this is a story not simply about a woman named Irene whose son commits suicide, but one that is meant to be emblematic for an entire continent and an entire historical period—the film's "now." Of course, any character can be seen in essentializing terms as "representing" an age; the difference here is that this fact is so firmly insisted upon that virtually no other possibility remains. Though Europa '51 avoids

being a film about people in general or "human nature," because it is a film about people at a very specific historical juncture, it clearly presumes to tell us about "all people" in this time and place.[7]

Other themes reappear, including the one that defines so much of Rosselini's career, the war. Except for the background of the camp from which Karin, in Stromboli , wants so desperately to escape, however, this is its first reappearance since Germany, Year Zero . But Rossellini does not go back to the bombed-out cities, as he was urged to do by his well-meaning supporters who wanted him to return to his "authentic self." Instead, the war functions as a moral horizon that has redefined the human condition; the subject is no longer the killing of the body that so occupied the first two films of the postwar trilogy, but rather the spiritual killing so painfully present in Germany, Year Zero . Now the spiritual decay, the director suggests, has spread beyond the destitute inhabitants of Berlin to encompass the middle class as well.

Nor is there any relief available through the coralità that redeemed the horrors of Open City and Paisan . A possibility is briefly offered early on, when we encounter Irene playing the charming hostess for her society parties. We understand soon enough, however, that this is a false coralità , an inauthentic subgroup (unlike that of the Franciscans) that will turn on Irene the moment she asserts, like so many other Rossellini women, her difference. Irene's difference from the group cannot be tolerated, however unthreatening it may appear to us, and a character at the end of the film overtly recalls the men to their duty to "protect society" from the likes of her. Society defends itself by marginalizing these threats, categorizing them as mad or "abnormal." Nanni, Karin, Francesco, and now Irene: the differences among them more a matter of degree than of kind. The coralità of earlier films is thus bitterly reversed, and that which had earlier fostered the individual now kills.

Like other films of this period, Europa '51 , to the dismay of those critics who would make of Rossellini the supreme realist, quickly announces its stylized, expressionist mode. It opens with a car cruising through wet, visually rich streets, an opening that will be repeated and reach its expressionist peak in Fear . In an early scene the boy complains to his mother that his teacher "gets too close"—another reference to Germany, Year Zero meant, as in the earlier film, to stand for a more global sense of corruption that affects society at all levels. During this discussion to which the mother barely attends, the camera focuses on the boy and his obvious lack of affect, while she speaks offscreen. In conventional terms, it is rather early in the film to separate voice and body in this way, but here it serves nicely as a visual-aural manifestation of the disjunction between them. The boy casually pretends to strangle himself with his mother's necklace (recalling a similar gesture in Una voce umana ), and the necklace, as a synecdoche for her socializing, operates efficiently as a causal analysis of his later suicide attempt. (After his death, his picture turns up in several scenes, always between the actors, suggesting the ongoing accusatory force of his moral presence.)[8]

An active, expressionist camera is present from the first. Constant dollies, here filling the role later taken up by the development of the Pancinor zoom

lens, seem to offer instant intimacy with the characters, but since this intimacy is always blocked—at least at this point in the film—the spectator's attempt to grasp the purposely two-dimensional characters is continually frustrated. The camera also catches the immediacy of the boy's suicide attempt. The camera is absent when it happens, which is appropriate considering the difficulty of filming a convincing suicide attempt, but also because the absence of the camera marks the absence of any concern, parental or otherwise, toward the boy. Instead, the camera chillingly replicates his quick, fatal movement up over the railing and down the circular stairwell. (In addition, Rossellini explicitly mentions in a later interview the importance of the jagged rhythm that has the boy attempt suicide, seem to recover, and then, when least expected, die.)

The absolute horror of the suicide provokes a traumatic moment in the life of the protagonist.[9] Rossellini's aesthetic of the existential moment has been clearly in evidence before (the suicide at the end of Germany, Year Zero and the revelations of transcendent meaning at the end of Stromboli ) and will be again at the end of Voyage to Italy . Here the difference is that the traumatic moment comes near the beginning of the film, and instead of the narrative being resolved in these epiphanic, transcendent terms—to which one is able only to assent in the other films, since they are instantly over—the rest of Europa '51 is, uniquely, a working out of the consequences of that moment. Europa '51 also stages a moment of realization at the end, but this epiphany more closely resembles those of Paisan , where the realization of the moment's meaning occurs principally within the spectator, rather than the three separate groups of characters depicted (the insensitive rich, Irene's family; the uncomprehending poor, Irene's adopted family; and Irene, now reduced more to suffering victim than active naysayer to society's corrupt values).

Strangely, it is not until sometime after the suicide attempt, when Irene is seen in the car with her Communist cousin, Andrea, that we actually learn that the boy died of a blood clot.[10] Before this, the spectator is unsure of what has happened—characteristically, Rossellini is in no hurry to elucidate things—and it seems at first as though he has attempted suicide again, this time successfully. Andrea takes Irene to Michelangelo's Campidoglio in Rome, which contained, at the time the film was made, an original classical statue of Marcus Aurelius that visually and ironically opposes the profound values of antiquity to those of the present day, in the manner of Godard's film Contempt . For the Communist, however, the point is to place Irene's problems in the context of present, rather than past, history, to combat her overwhelming sense of individual guilt. He tells her, as a good materialist, that she must begin to pay attention to "things as they are." When she insists that it is either her fault or society's, he replies, in what must be the most unconvincing line in the entire film, "Blame this postwar society." Later, of course, Irene will reject the Communist answer along with all the others, and a lively debate has arisen concerning the portrait of the Communist that this film offers. At this point, however, the Communist is regarded in a clearly favorable light; if his answer is not the correct one, finally, because it is as overly programmatic and "rational" as the others, he nevertheless serves the important function of moral catalyst for Irene, allowing her to see the world in a new light. When he mentions the injustice of a little boy who is dying

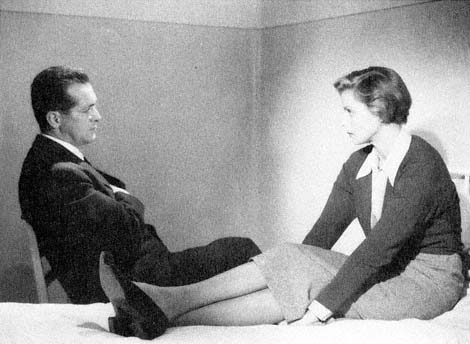

The ubiquitous Rossellini automobile: Irene (Bergman)

with her Communist cousin (Ettore Giannini), in Europa '51 (1952).

because his family does not have enough money to pay for his expensive drugs, Irene is motivated enough to transcend her narcissistic suffering and begin moving beyond the concerns of self toward the service of others.

Another important nexus of the film's themes comes up in Irene's encounter with "Passerotto" ("Little Sparrow"), a down-to-earth representative of the working class played by Giulietta Masina. (Her dubbing into English has unfortunately turned her into an Italian Shelley Winters, but as Robin Wood has pointed out, the dubbing problem in the Bergman-era films simply must be overlooked by the viewer who does not want to get mired in the ultimately superficial.) With her brood of fatherless children, she stands in clear opposition to Irene: as a woman who is presumably more closely in contact with the realities of life, she represents the vibrancy of the life force itself, in contrast to Irene's sterility. It must be insisted, however, that no one-to-one, simplistic equation is made between having children and natural happiness—it is Masina's vitality in general that Rossellini seems to approve of. It has also been argued by some Marxist critics that aligning Passerotto with the "life force" in this way is also a form of popolismo , the not uniquely Italian error of idealizing the working classes. Rossellini gets around this charge, however, by thoroughly demystifying the poor and downtrodden people portrayed in the film. Thus, when Irene manages to find Passerotto a job in a factory, Passerotto decides that a date

with her boyfriend is more important than showing up on what was to be her first day at work. Irene is persuaded to fill in for her—setting the stage for the most powerful scene in the film—but Passerotto's refusal to give up the immediate gratification of meeting her boyfriend for a middle-class notion of getting ahead is significant, and gives evidence of a sophisticated sense of class value systems. Rossellini's clearly favorable portrayal of Passerotto in all other ways works nicely against our own bourgeois offense at her lack of interest in the factory job, and renders her character as complex and many-sided, and as finally irresolvable, as any other in the film. This act of demystication is repeated later when Irene helps a prostitute who, instead of being eternally grateful, turns out to be quite grumpy and thankless.

When Passerotto asks Irene to fill in for her at the factory, Irene says that she would have no idea what to do there. Passerotto replies, with incontrovertible logic, "Neither would I." Unable to respond, Irene goes to the factory. Suddenly, the whole texture of the film changes: the rather stylized realism that has prevailed turns into the harsh graininess of the documentary sections of La macchina ammazzacattivi . We see Irene entering the factory with obviously real workers, who assert their reality, and thus clash with the codes of realism, by defiantly looking straight into the camera, momentarily destroying the fabric of the film's illusionism.[11]

The sequence shot inside the factory is immensely powerful. It recalls at once the expressionist scenes of the underworld of industrial life in Lang's Metropolis and Rossellini's own footage in La nave bianca , in which the mechanical bowels of the ship are shown simply for the sake of their dynamic, demonic interest. Irene and the other human figures are lost in extreme long shots that dwarf and isolate them. Huge, whirling machines reduce her to a nonentity, she who has been so selfish and egocentric, while the overpowering noise assaults her senses. A close shot brings her face up to us, and we see her eyes bob violently up and down, trying to keep track of the workings of the machine she has been assigned to. Rossellini's editing takes an Eisensteinian turn here, as it had ten years earlier, becoming faster and faster, upsetting us, but managing to convey at the same time the thrill of the machine's inherent vitality as it spits out its product. Quick cuts between a close-up of Irene's face and the pounding of the metal press link the two emotionally for us; she is clearly on the edge of breaking down. The film then cuts suddenly to a scene of "polite society" to emphasize the contrast.

George, Irene's husband, reacts to her quest in a typically patriarchal way, assuming that the only reason for a "woman of her class" to be involved in such foolishness is another man. The Communist Andrea, by earlier making an amorous advance to Irene, has put himself into this same system of values, which the film clearly insists is beside the point . Neither man is able to understand that Irene's values occupy a different register. Having earlier spurned Andrea's advances, she now turns down his Communist philosophy as well, and this has not endeared the film to Communist critics. It is certainly true that Andrea's Marxism is not very sophisticated, offering as it does a picture of an earthly paradise that will be realized when the revolution is victorious. But, not surprisingly in a film by the director who made The Miracle, Stromboli , and

Francesco , Irene insists that "the problem is much deeper than that, it's spiritual." She wants God to help her in her search "for the spiritual path." She needs the possibility of a life where there is also a place for her dead son, as she says, not just an earthly paradise for the living. She articulates a philosophy of love that is clearly Franciscan in inspiration.

What has particularly bothered Marxist critics is that her experience in the factory leads Irene to reject not only the promise of an earthly utopia, but also the very worth of work itself. When Andrea suggests that work ennobles, Irene insists that it is horrible. Naturally, this condemnation is troublesome, coming from a rich bourgeoise after one day spent getting her hands dirty. Yet, Rossellini and Irene are clearly talking about the alienating assault on the mind and body that most labor in an advanced moment of the industrial age has become, and no serious Marxist would want to argue that factory work as presently constituted in capitalist countries is anything but deadening.

If Irene rejects politics, however, the Church is not the answer either. We remember that it failed Edmund, Nanni, and Karin, and it fails Irene as well. As the chiaroscuro of the visuals becomes more pronounced in the final section of the film, indicating her deepening spiritual and psychological crisis, Irene heads for a church. As in the earlier films, the whole scene is handled without a single word of dialogue: she walks up the stairs, goes in, looks uncomprehendingly at the priests, the baroque altar, and some old ladies dressed in black, and goes back out the door. The Church is clearly the place of the dead, and only the dead; while it supplies the spiritual element missing in communism, it is unable to minister to the living.

Irene next encounters the ungrateful prostitute who is dying of tuberculosis. In a lovely series of visuals, Irene goes out into the night in search of a doctor for the woman, and a long shot appropriately emphasizes her new isolation. For by helping a prostitute, she is performing an act of charity that not even any honest working-class person would perform, thereby implicating them as well in the general critique of modern society. Her situation has become analogous to that of Eliot Rosewater in Kurt Vonnegut's novel God Bless, You, Mr. Rosewater (1965): she wants to help people simply because they need help, irrespective of all other factors, and thus she is thought insane. Since the vast majority of us have already succumbed to what Vonnegut calls "Samaritrophia," we need to call these people crazy. Irene gets so caught up in the prostitute's problems that we become uncomfortable, especially when she cries for her as though she has known her all her life. Isn't she overdoing it? Or is she simply being a good Christian? Again, Rossellini refuses to clarify the complex issue. As the prostitute dies, the camera briefly catches what looks like a picture of Saint Francis on the table next to her bed.

When Irene next becomes involved—rather quickly, and thus completely unrealistically—this time in the getaway of a young bank robber from the neighborhood, she tries to get him to give himself up voluntarily, but will not turn him in herself. At this point, she has finally crossed beyond what society will legally permit; the policeman to whom she attempts to explain the situation refuses to consider anything beyond the sheer letter of the law, in all its glorious abstraction from the exigencies of the moment. Her case is handled by three

men—whereas most of her group of supporters and friends are women—and all of officialdom, including her family, want to attribute her craziness to the death of her son, in order, obviously, to explain and thus domesticate the irrationality of her behavior. Her husband treats her like a child and worries about all the publicity as he pilots his obscene Cadillac through the narrow streets of Rome.

The hospital they take Irene to is white and sterile, and Rossellini succeeds in conveying, as Hitchcock does in The Wrong Man , a visceral sense of what it would be like to be locked up against one's will. She is stuck in a room with no door handles on the inside, and the family sneaks off without a word of explanation. She does get sympathy from the hospital maid, across class lines, and appropriately again, from a woman. Against all odds, Irene manages to remain calm, even when she is brought into the "lounge" area, where the camera works out a stylized waltz that brings us violently up against one madwoman after another. The suggestion is that this is a subjective shot from Irene's point of view, but it carries a third-person feel as well, and thus does not naturalize and domesticate the madness we see before us by attributing the perception to Irene. The testing she next undergoes is as dehumanizing and psychologically violent as her day in the factory.

Rossellini's critique of organized religion is continued with the visit of the hospital's chaplain; the light that streams through the cell's windows and onto its sterile walls conjures up the church we saw earlier. The priest, just like the other males—judge, policeman, husband, and Communist—misunderstands as well because he cannot think beyond the hidebound rules he lives by to the human reality that the rules were originally meant to address. Irene offers a radical spirituality, not really much different from the radicality of Christ's teaching, but which organized religion has been at some pains ever since to tame: she tells the priest she wants to love all people as the sinners they are, instead of trying to change them. Looking more and more like Saint Joan, she insists that if this is done, a great spiritual force will take over and grow.

The psychiatrist next goes to work on her, grilling her about the "force" inside her. "Are you dominated by the great spiritual power of the saints?" he asks, "No," she replies, rejecting the connection with Saint Joan, "then I'd be crazy." "Then it's love?" "No, it's hate for all the things I was before, hatred for myself." Her words make sense, but isn't self-hatred also pathological? The men who consult to decide her fate cast their decision, as might be expected, in thoroughly linear, either-or terms: is she insane or is she a missionary? There is no other choice possible for them: society must be defended, they say. The priest questions her regarding her plans, and she confounds them again by saying she does not want to go home because she is sure that she would inevitably fall back into her old ways. She wants to devote herself to the people who need her, she says, not her husband, for her love is wider than that. "When you're bound to nothing," she says, in the film's most direct statement of Franciscanism, "you're bound to everybody."

The decision is made: she is to be committed. She looks saintly in her spare, sterile room; she has finally become Saint Francis, with all the ambivalence that attaches to him. She looks out through her bars and, in an economical and resonant image, we see her insensitive family moving away from her and the

Irene being interviewed by a psychiatrist in the asylum in Europa'51 .

asylum in their Cadillac, while her loyal followers, the poor folks led by Passerotto, move toward her, chanting their love and admiration. It is a perfect moment of synthesis, as the poor proclaim her sainthood. The last, quite moving shot shows Irene's ravaged face, through the bars of her cell. From her eyes come what Eric Rohmer has called "the most beautiful tears ever shed on a screen."[12]

Even at the very end, and beyond, we still do not know how to take her. Irene is obviously the innocent victim of society's insistence on conformity—Rossellini's idea of the film's theme at the time[13] —but her extreme devotion to the poor does seem "abnormal" as well. More importantly, questions have been raised concerning the film's politics (Rossellini naturally maintaining no political views were expressed). Some have attacked the director for once again cloaking his suffering heroine in the obnoxious robes of religion and mysticism. Guido Aristarco has even attempted to turn the director's accusation on himself, by claiming that his denunciation of conformity and moral deafness is similar to those who "knowing themselves to be guilty, accuse others of the same fault."[14] Gianni Aiello has also brought up the vulnerable point of Irene's subjective motivation, insisting that her desire for solitude "stems only from personal motives, and has no objective justification. Thus the 'ideological' weakness of Rossellini takes shape."[15] Even a supporter like Gianni Rondolino has suggested that the problem with the film is that its depiction of society's problems is too closely wrapped up with that of Irene's own problems.[16]

By the 1970s, however, many younger critics and students, with the experience of 1968 behind them, were able to see the film's politics in a new light. Baldelli's seminar, to which I have referred earlier, is instructive in this regard. Some of the students still expressed strongly negative views of the film (even in Rossellini's presence), but others regarded it more favorably. It is easier for us to see now that, given the choice between the rigid dogmatism of the Communist party of the early 1950s, and the rigid dogmatism of the Church, Rossellini was trying to strike out into new territory, a territory that would exceed the limitations of binary thinking. As one of Baldelli's students rightly suggested, the film can in some ways be seen as a long, complex (and unresolved) meditation on the relation of political practice to the political theory offered by the leftist in the film.

Another debate on Rossellini, also held in the early 1970s, the transcripts of which have been collected by Gianni Menon in a book entitled Dibattito su Rossellini , shows signs of the same change in critical and political perspective. Enzo Ungari, for example, stresses the fact that Europa'51 is, in spite of appearances, very political in its anticipation of the late-sixties revolt against orthodoxies of all stripes. He sees Irene's story, perhaps somewhat improbably, as the refusal of false consciousness, for to be really political for others, one must free oneself from all ideological schematism, and this is precisely what Irene does. Others in the debate felt that it would be a useful film to show on television because it would reach the masses, and serve as a "toned-down" mediator between the official cinema and more overtly leftist filmmaking. Maurizio Ponzi has elsewhere taken a similar position, maintaining that "at the ideological level, it is a subversive film, the revolution made film, because it doesn't judge, it doesn't insist, while at the same time it follows a story which protests in every frame."[17]

Perhaps the final word on this film and its openness to interpretation should be left to the eloquent Adriano Aprà. During the debate transcribed in Menon's book, he declared:

Rossellini is a terrorist, like Irene in Europa '51: he puts you face to face with your personal responsibilities. You are either with me or against me. No compromises are permitted, no "we'll see later": you have to take a position, immediately. This evening many have rejected not the film, but a position, opposing an alleged rationality to a presumed irrationality. In so doing, they have rejected the possibility of a whole man and the necessity of error.

Instead, it is necessary to make mistakes because making mistakes is life. Death does not make mistakes, it doesn't discuss or choose; all the dead are equal, they don't bother us, because corpses don't have eyes to look at us. Rossellini's films look at us straight in the eye. When a man looks at you in the eye, you either turn and run or you go toward him and by this action fulfill yourself.

The majority of Italian cinema is a cinema of the dead, and "realistic" in the sense that it shows us how we are, it puts us at peace with ourselves, it conciliates, it does not show us what we are not and how we could become that. It's a cinema of peace, of pacification, while that of Rossellini is a cinema of war, of guerilla action, of revolution.[18]