Six—

Forging a New Linguistic Identity:

The Hindi Movement in Banaras, 1868–1914

Christopher R. King

Introduction:

Indo-Persian and Hindu Culture

Queen Abode-of-Truth is speaking, testifying before the court of Maharaja Righteous-Rule on behalf of Queen Devanagari:

Here's where Nagari dwells, here her own dear country,

Here our queen was born, in sacred, holy Kashi.

(Datta 188?:8)

A little later Begam Urdu speaks on her own behalf before the Maharaja:

Persian is my mother, Urdu is my name.

Here my birth took place, and here I will remain.

(Datta 188?:10)

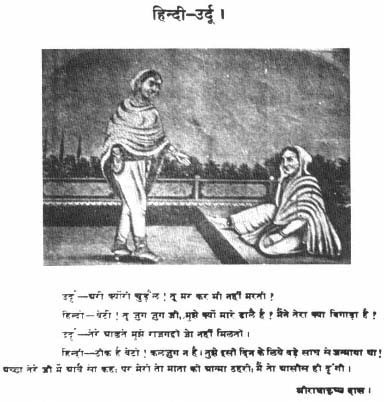

Each woman claims India as her birthplace, and each asserts her right to rule (see fig. 14). As this late-nineteenth-century Hindi drama develops, the reader soon realizes that the verdict will favor Queen Devanagari, and that the author, Pandit Gauri Datta of Meerut, has passed chiefly "moral" rather than technical judgments in presenting the dispute between the two personified languages and scripts.[1]

The entire action of the play, a short one-act work in the folk theatre tradition of svang[*] (see chapter 2 in this volume) takes place in a courtroom over which Maharaja Righteous-Rule presides. Babu Moral Law

[1] Datta's play, judging from internal evidence, seems to have been presented several times, and the audience may well have included visitors to local melas (religious fairs). Thus in April 1889, Datta's own newspaper, the Devanagari Gazette of Meerut, reported that four dramas, including at least one critical of Urdu, had been performed by Hindi advocates at a recent mela, and printed the first and last acts of this play (NWP&O SVN 1889:284).

Fig. 14

"Begam Urdu," in the garb of a courtesan, addresses "Queen Devanagari," attired

as a proper Hindu wife. Illustration for a svang[*] text printed in the periodical

Saraswati (1910). Courtesy of the Allahabad Public Library. Special thanks to

Sanjay Sharma for research assistance.

Singh argues for Queen Devanagari, and Mirza Cunning Ali Khan for Begam Urdu. Queen Devanagari complains that Begam Urdu has usurped her former rule over all works of wisdom and virtue, as well as letters, papers, account books, bonds, notes, and official documents. She testifies that she teaches righteousness and removes falsehood, and that under her rule people could make merry, become wealthy, carry on their business, and learn wisdom.[2] Bribery, continues the Queen, would weep at the very sound of her name, and fabrications and fraud would disappear should she rule again. Her witnesses all attest to her good name, sterling character, and indigenous origins. Indeed, as we

[2] Datta may be intentionally echoing the Hindu doctrine of the four ends of life.

saw above, her birth takes place in the hallowed location of Kashi—an older name for the largest of the several sacred zones of Banaras (Eck 1982:350). In short, Queen Devanagari embodies many of the moral and religious values of the Hindu merchant class described by Bayly, especially the core value of credit (sakh ) (Bayly 1983:375–93). "The behaviour and ideals of the merchant family firm were . . . directed to survival first and foremost, but survival here meant above all the continuity of family credit within the wider merchant community" (381). Queen Devanagari, through her righteousness, guarantees the continuing "credit" of business and government records, while Begam Urdu, through her corruptness, threatens the inextricably combined moral and economic well-being of society.

Begam Urdu defends herself by arguing that although her mother, Begam Persian, was foreign, her own birth took place in India, and therefore she has a right to stay. She describes her own work, however, in terms hardly calculated to make a good impression on her judge:

This is my work—passion I'll teach,

Tasks of your household we'll leave in the breach.

We'll be lovers and rakes, living for pleasure,

Consorting with prostitutes, squandering our treasure.

Give heed, you officials, batten on graft,

Deceiving and thieving till riches you've quaffed.

Lie to your betters and flatter each other.

Write down one thing and read out another.

(Datta 188?:10)

Her witnesses, too, bear names unlikely to mollify the judge: Begam Twenty-Nine Delights, Prince Passion-Addict Khan, Begam Wanton-Pleasure, and Emperor Ease-Lover. Urdu's witnesses all testify to the licentiousness and depravity of their mistress and the pleasures that follow in her train.

The climax of the play sees Queen Devanagari's lawyer making an impassioned plea for his client. By restoring the former monarch to her rightful place, the age of falsehood would become the age of truth, fraud would vanish, good deeds would multiply, people would feed Brahmins, hatred and strife would disappear, enemies would become friends, everyone would become clever, and every child would study Nagari in school. Begam Urdu's lawyer in his final summation points to the British recognition of Urdu and claims that should Nagari try to perform the work of courts and offices, everything would become topsy-turvy. In an inversion of the actual power structure of society at the time (typical of the svang[*] —see chapter 2) Maharaja Righteous-Rule brings the case to a close with his judgment, made in accordance with the sacred law of the Hindus: let Urdu be cast out and Nagari take her place (Datta 188?:13–14, 16).

Language and the Formation of Community Identity

Many studies of the Hindi movement have focused on the political aspects, especially at the national level, and have dealt primarily with the twentieth century (for example, Brass 1974; Das Gupta 1970; Gopal 1953; Harrison 1960; Kluyev 1981; Lutt 1970; S. Misra 1956; Narula 1955; Nayar 1969; Smith 1963; Tivari 1982; L. Varma 1964). The great majority of these have used chiefly English sources, and few of them have thoroughly surveyed the relevant sources for the nineteenth century. Almost no studies have attempted to trace the detailed history of the voluntary language associations that played such major roles in the development of Hindi. In this essay I examine not only the political but also the social and cultural aspects of the Hindi movement, particularly on the local and provincial levels, and deal chiefly with the nineteenth century. Moreover, I have made extensive use of both Hindi and English sources, including a thorough search of official records, such as education reports, publication statistics, and the like. Finally, I stress the importance of voluntary language associations, which both reflected and intensified the Hindi movement (see also King 1974).

The play described above well illustrates the social, cultural, and political matrix from which the Hindi movement arose, namely, the growing split between Indo-Persian and Hindu merchant culture characteristic of the late nineteenth and the early twentieth century in north India. As Bayly (1983) has shown in his analysis of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century north India, these two "conflicting forms of urban solidarity" served as the foundations of the later-developing nationalism and religious communalism, which so dramatically affected events in the twentieth century. Urdu effectively symbolized the dominant Indo-Persian culture of north India in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, for it formed one of the major parts of this blend. The attack on Urdu and the strong support for Nagari (a term that encompassed both language and script) evident in the play became important elements in the process by which a self-conscious Hindu nationalism emerged in north India. Part of this process involved the separation from and rejection of earlier symbols of joint Hindu-Muslim culture, and part entailed the definition and affirmation of newer communal symbols. Moreover, this process also involved the complete disregard or rejection of various forms of written or oral popular culture, such as Hindustani, the regional dialects (e.g., Braj Bhasha and Bhojpuri), and variant scripts (e.g., Kaithi).[3]

[3] Braj Bhasha and Khari[*] Boli[*] are the major regional dialects in western U.P., Awadhi in central U.P., and Bhojpuri in eastern U.P. and western Bihar. The first three had major written as well as oral traditions during our period, the fourth only oral. Kaithi, Mahajani, and Muria are cursive variants of the Nagari script, associated with certain Hindu merchant castes and famous for their ambiguity.

This process of separation and differentiation between the Indo-Persian and Hindu merchant cultures led to a shift: the overlapping literary cultures came to function separately, following a new identification of "Hindu" with Hindi and of "Muslim" with Urdu. This shift came about through a wide variety of means, many of which lend themselves to some form or other of measurement. Among these are the development of voluntary organizations to promote languages and scripts; the standardization of languages through dictionaries, grammars, and other publications; newspaper campaigns for or against languages and scripts; systematic searches for, and publication of, old manuscripts; the introduction of large numbers of Sanskrit and Arabic and Persian words into Hindi and Urdu respectively; the publication of books and periodicals, especially elementary- and secondary-school texts; and the production of vernacular literature attacking the joint Hindu-Muslim cultural tradition, especially as it was expressed in Urdu. The "Hindu" and "Muslim" of this shift, however, do not include the Hindu and Muslim masses, but rather refer to a "vernacular elite," that is, Indians educated in the vernaculars and in competition for government service. Likewise, "Hindi" and "Urdu" refer not to the regional and local dialects of the bulk of the population, but rather to carefully cultivated literary dialects, strongly linked to the corresponding classical languages of Sanskrit, Persian, and Arabic.

During our period Banaras played the leading role in the process outlined above. Long famed in India as a center of Hindu learning and religious pilgrimage, by the early nineteenth century the city had also become a major center of Hindu literature (Grierson 1889:108–9). Bharatendu Harishchandra and Raja Shiv Prasad were only two of the most eminent literary figures of the second half of the century to live in Banaras. The peak of the city's influence on the gradual process of the emergence of modern Sanskritized Hindi as an important symbol of Hindu nationalism came with the founding of the Nagari[*] Pracharini[*] Sabha[*] (Society for the Promotion of Nagari) in 1893.

This organization, the majority of whose membership came from the eastern part of the North-Western Provinces and Oudh (NWP&O), remained the single most influential force for Hindi until the eve of World War I, when a gradual decline in membership, and an increasing concern for things literary and a decreasing concern for things political in the Sabha's leadership, allowed the Hindi Sahitya Sammelan (Society for Hindi Literature) of Allahabad to become the premier Hindi institution. This shift from Banaras to Allahabad also roughly coincided with a shift in the scope of the controversy between Hindi and Urdu from the provincial (NWP&O) to the national level. Significantly, one of the ironies of the Hindi movement is that neither of these organizations promoted popular culture in the form of the re-

gional and local dialects that surrounded them, though both spoke for the welfare of the Hindu majority of the population in the "Hindi-speaking" areas of north India. Let us now focus on the process of linguistic and social change in the NWP&O and other parts of north India, and on some of the most important means through which this came about.

Old Identities:

The Terminus a QUO

In 1847 a noteworthy encounter took place between Dr. J. F. Ballantyne, principal of the English Department of Benares College, and several students of the Sanskrit College (also part of Benares College). After various unsuccessful attempts to "improve" the Hindi style of his students, Ballantyne lost his patience and directed them to write an essay on the question "Why do you despise the culture of the language you speak every day of your lives, of the only language which your mothers and sisters understand?" (NWP Educ Rpt 1846–1847:32). The ensuing dialogue produced several striking statements that clearly indicated that Sanskritized Hindi had not yet become a symbol of Hindu as opposed to Indo-Persian culture. Ironically, this situation existed among students of the very institution which the founders of the Nagari[*] Pracharini[*] Sabha[*] (NPS) would attend nearly half a century later. An apparently puzzled student spokesman told Ballantyne:

We do not clearly understand what you Europeans mean by the term Hindi, for there are hundreds of dialects, all in our opinion equally entitled to the name, and there is here no standard as there is in Sanskrit. (NWP Educ Rpt 1846–1847:32)

The same student went on to say:

If the purity of Hindi is to consist in its exclusion of Mussulman words, we shall require to study Persian and Arabic in order to ascertain which of the words we are in the habit of issuing every day is Arabic or Persian, and which is Hindi. With our present knowledge we can tell that a word is Sanscrit, or not Sanscrit but if not Sanscrit, it may be English or Portuguese instead of Hindi for anything that we can tell. English words are becoming as completely naturalized in the villages as Arabic and Persian words, and that you call the Hindi will eventually merge in some future modification of the Oordoo, nor do we see any great cause of regret in this prospect. (NWP Educ Rpt 1846–1847:32)

If his students did not yet have a national goal for Hindi, then Dr. Ballantyne did. In reply to this perception of Hindi as a cluster of unselfconscious vernaculars rather than a refined literary language, he urged:

It was the duty of himself and his brother Pundits not to leave the task of formulating the national language in the hands of the villagers, but to endeavour to get rid of the unprofitable diversity of provincial dialects, by creating a standard literature in which one uniform system of grammar and orthography should be followed; the Pundits of Benares, if they valued the fame of their city, ought to strive to make the dialect of the holy city the standard of all India, by writing books which should attract the attention and form the taste of all their fellow countrymen. (NWP Educ Rpt 1846–1847:32)

Ballantyne's uncannily accurate vision of the future of Hindi struck no responsive chord in the thoughts or feelings of his students. The disappearance of Hindi into Urdu aroused no sense of alarm in these Hindi scholars of Sanskrit, nor did they see any necessary connection between being Hindu and speaking Hindi. Moreover, since the very term "Hindi" struck them as vague and ambiguous, no standard having emerged, we may tentatively conclude that these students would have included the regional and local dialects, the vehicles of popular culture, under this rubric. Ballantyne, on the other hand, clearly intended to separate Hindi from the confused mass of popular dialects, to reject any conceivable influence of villagers on "the national language," and to define and affirm Hindi in terms of a standardized and Sanskritized language created by a vernacular elite.

A decade before Ballantyne's encounter with his students, English and various local vernaculars had replaced Persian in British India. In north India, with one or two exceptions,[4] this meant that Urdu in modified form of the Persian script became the official vernacular. The original purpose of replacing Persian had been to make the official proceedings of courts and offices intelligible to the people at large; thus in 1830 the Court of Directors of the East India Company had intoned that "it is easier for the judge to acquire the language of the people than for the people to acquire the language of the judge" (Malaviya 1897:497), overlooking or ignoring the fact that the great bulk of the population had no acquaintance with either spoken or written Urdu.

Very soon, however, the excessive Persianization of the new court-language of north India made a mockery of the supposed reason for which the change had been made. As early as 1836, for example, the Sadar Board of Revenue of the North-Western Provinces (N.W.P.) had warned division Commissioners that the replacement of Persian by Urdu did not mean "the mere substitution of Hindee verbs and affixes, while the words and idiom remain exclusively Persian" (NWP Lt-Gov

[4] Among the exceptions were the Saugor and Nerbudda Territories in the mid-1830s—see King 1974:66–70, 149–54—and the Kumaun division of the NWP&O throughout our period.

Prgs SBRD 19 July to 2 August 1836:Range 221, Volume 77, Number 52). Yet nearly two decades later, exactly this had happened, for the then lieutenant-governor of the N.W.P. felt obliged to inveigh against the style of official Urdu, "little distinguished from Persian, excepting the use of Hindee verbs, particles, and inflections" (Malaviya 1897, Appendix:52). Official protests and notifications did little to change this state of affairs, however, and complaints about the excessive Persianization of court Urdu appeared regularly, well into the twentieth century. In general, British support for Urdu did much to assure the continued dominance of this symbol of Indo-Persian culture. In the province, the heartland of the Hindi movement, most gains for Hindi and the Nagari script in courts and offices came in the face of government neglect or opposition.

At this point, let us posit a spectrum of linguistic popular usage for north India during our period: the term "popular" should be understood in a relative rather than an absolute sense. At one end of this spectrum comes English and at the other, local dialects. In between we have, first, the classical languages Sanskrit, Arabic, and Persian; then, Urdu followed by Hindi; next, Hindustani (in the sense of a language style less Persianized than Urdu, and less Sanskritized than Hindi); and finally, the regional dialects such as Bhojpuri and Awadhi. From this viewpoint Hindi ranks as more "popular" than English or Urdu, but less so than Bhojpuri. The bulk of the supporters of the Hindi movement in Banaras and elsewhere in the province came from the ranks of the vernacular elite, those educated in the more standardized vernaculars of Hindi and Urdu, not from the English-speaking elite on the one hand, nor from the regional- or local-dialect-speaking masses on the other.[5]

The potential for differentiation and separation between the two different sections of the vernacular elite existed long before the 1860s, when controversy between supporters of the more "popular" Hindi and the less "popular" Urdu first began. Bayly concludes that "some of the conditions which fractured the life of modern north India into Hindu and Muslim camps must be dated much earlier than is commonly supposed" (Bayly 1983:455). Similarly, as we shall see, considerable evidence indicates that the potential for linguistic controversy stretched back to the early nineteenth century and before. We must ask, then, what influences kindled underlying differences into open conflict in the 1860s. In general, the pace of economic and social development in the province quickened after the Rebellion of 1857 in a wide variety of ways (see Bayly 1983:427–40). Most important for our

[5] This picture may be too starkly drawn, however, since many Hindi speakers knew some English, and most or all of them undoubtedly knew regional or local dialects.

purposes, however, was the rapid post-Rebellion expansion of the three closely related areas of government service, education, and publication (all discussed below). Each of these institutionalized the most refractory difference between Hindi and Urdu—script—and each became an arena of competition in a mutually reinforcing and ever-expanding spiral.

Definition against External Rivals:

The Hindi-Urdu Controversy

The Hindi-Urdu controversy, as the long and heated exchange of opinions between opposing supporters of Hindi and Urdu came to be known, began in the 1860s and continued right up to Independence. Confined largely to U.P. in the nineteenth century, the controversy gradually assumed national proportions in the twentieth. On both the provincial and the national level, a major portion of the debate focused on the question of the proper language and script for government courts and offices. The center of the Hindi side of the controversy lay in the eastern districts of the province and especially in the cities of Banaras and Allahabad.

The themes announced early in the controversy appeared again and again with wearying consistency. The protagonists of Hindi argued: the bulk of the population used Hindi; the Urdu script had a foreign origin, and also made court documents illegible, encouraged forgery, and fostered the use of difficult Arabic and Persian words; the introduction of the Nagari script into government courts and offices would give considerable impetus to the spread of education by enhancing the prospects for public service; and experienced Hindi scribes could write just as fast as their Urdu counterparts. The supporters of Urdu maintained: even the inhabitants of remote villages spoke Urdu fluently; the Urdu language had originated in India even though its script may have come from outside; any script could lend itself to forgery; the numerous dialects of Hindi lacked standardization; and Hindi had an impoverished vocabulary, especially in scientific and technical terms. One of the most often repeated arguments for Hindi appeared in blunt numerical terms, where speakers were identified by religious community. An 1873 issue of the Kavi Vachan Sucha[*] , a Hindi newspaper of Banaras, argued that the government's duty lay in yielding to the demand of the general public for the introduction of Hindi. Although the Muslims might suffer from the change, they constituted only a minority of the population, and the interests of the few always had to yield to those of the many (NWP&O SVN 1873:528). Such arguments, of course, ignored the fact that the great bulk of the population used nonliterary regional and local dialects, and not the Sanskritized Hindi and Persianized Urdu of the vernacular elite.

Throughout the controversy the participants tended to identify language and religion. In 1868, Babu Shiv Prasad, a prominent advocate of the Nagari script, castigated British language policy, "which thrusts a Semitic element into the bosoms of Hindus and alienates them from their Aryan speech . . . and . . . which is now trying to turn all the Hindus into semi-Muhammadans and destroy our Hindu nationality" (Prasad 1868:5–6). Professor Raj Kumar Sarvadhikari, appearing before the Hunter Education Commission in 1882, remarked that in Awadh "Urdu is the dialect of the Muhammadan inhabitants and Hindi of the Hindus" (Educ Comm Rpt NWP&O:462). Conversely, in 1900, a correspondent of the Punjab Observer expressed fears that the recent decision of the provincial government to recognize the Nagari script would eventually lead to the abolition of Urdu, which would in turn cause Muslim boys to become Hindu in thought and expression (Khan 1900:79).

From the very beginning the different parties to the debate consistently confused the names for language and script. "Hindi," "Hindi character," "Nagari," and "Nagari character" seemed interchangeable, as did "Persian," "Persian character," and "Urdu." Sir George Grierson, author of the massive Linguistic Survey of India , remarked that "these fanatics have confused alphabet with language. They say because a thing is written in Deva-nagari [sic ] therefore it is Hindi, the language of the Hindus, and because a thing is written in the Persian character therefore it is Urdu, the language of the Musalmans" (Grierson 1903–1928, vol. 9, part 1, xiv, 49). Yet script was the critical issue. More than any other linguistic fact, the radically different nature of the two scripts rendered any solution to the Hindi-Urdu controversy intractable.[6] While the grammars of Hindi and Urdu, derived from the regional dialect of Khari[*] Boli[*] , were almost identical, and while the vocabularies of the two on the everyday level of discourse overlapped considerably, the two scripts focused and heightened the differences between the Hindu and the Indo-Persian cultures.

Like different channels to different cultural reservoirs, deliberately opened, they allowed the influence of Sanskrit, on the one hand, and of Arabic and Persian, on the other, to pour separately into Hindi and Urdu, bypassing the existing mixture of Indo-Persian culture. The results of this artificial irrigation, highly Sanskritized Hindi and highly Persianized Urdu, not only served to distinguish the rival Hindu and Indo-Muslim cultures from each other, but also sharply differentiated both from the surrounding ocean of popular culture.

[6] The Nagari script is syllabic, indicates all vowel sounds, has a chunky and square appearance, has a nearly continuous line across the top, and reads from left to right. The Urdu script (often referred to as the Persian script during our period, though it has several more letters) is alphabetic, does not indicate many vowel sounds, has a curved and flowing appearance, and reads from right to left.

Definition against Internal Rivals:

Hindustani, Braj, and Kaithi

The processes of separation and rejection, and of definition and affirmation, occurred not only between Hindi and Urdu, but also within the world of Hindi itself. Considerable controversy took place among Hindi supporters over the question of the proper style for literary works. Whatever the merits or demerits of the various styles current among Hindi authors, however, the reading public showed a definite preference for a simple style. The most popular author of the period, Devki Nandan Khatri (1861–1913), wrote in a clear and readable Hindi that made ample use of common Arabic and Persian words. His two best-known series of novels, Chandrakanta and Chandrakanta Santati , which he started writing in 1888, won him fame and fortune. Within ten years he had earned enough to found his own press in his native city of Banaras. For a few years Khatri became a member of the NPS, but found the atmosphere there uncongenial. From the viewpoint of the Sabha, although Khatri's works (published in the Nagari script) had won more readers than any other author (UP Admin Rpt 1914–1915:72), his style did not deserve to be considered literary Hindi, but rather only merited the designation "Hindustani," a vehicle fit merely for light and frothy creations and too close to Urdu to be respectable (R. C. Shukla 1968:476–77).

In the NPS the whole vexed question of the proper style for Hindi came to a head in a controversy between the Sabha and one of its own officers, Pandit Lakshmi Shankar Mishra, who served as president from 1894 until his resignation in 1902. Mishra possessed impeccable credentials: he held a high position in the provincial Educational Department, he had made efforts for the increased use of Hindi in government schools, and he had published in Hindi on the subject of science before most of his fellow scholars. The heart of the dispute appeared in a letter sent by Mishra to the provincial Text-Book Committee at the time of his resignation. After speaking of a "widening gulf" between Hindi and Urdu, Mishra went on to say:

As the Grammer of both Urdu and Hindi is identical, they should not be considered as separate languages, and hence for ordinary purposes, in such books as are not technical and which are intended for the common people, [an] attempt should be made to assimilate the two forms into one language, which may be called Hindustani, and may be written either in the Persian script or the Nagari character. (NPS Ann Rpt 1894:35–36, 40 41; UP Educ Progs May 1903:31–32)

Yet the raison d'être of the Sabha was the distinct and separate existence of Hindi vis-à-vis Urdu. Any attempt to combine them or to reduce or eliminate their differences undermined the whole purpose of the organization. Views such as those put forth by Pandit Mishra must

have been anathema to the other leaders of the Sabha,[7] and they could hardly tolerate the open expression of such opinions by their own chief officer. The leaders of the Sabha felt obliged both to differentiate their language and script from others and to reject any actual or potential rivals. In Sanskrit plays, characters of loftier social rank speak Sanskrit, while those of lower ranks speak lesser languages. Similarly, the Sabha gave great importance to preserving the Sanskritic purity of an important cultural symbol. In this way, the organization consciously chose to maintain linguistic contact with Hindu vernacular elites in other areas of India, rather than encourage popular culture and enlist the support of the masses of its own area (see Das 1957:251–52).

The Rejection of Braj Bhasha

In its first annual report the Sabha presented a picture of the rise and development of Hindi literature which showed a basic ambiguity (NPS Ann Rpt 1894:1–3). While claiming Braj Bhasha and other literary dialects as part of Hindi literature in the distant past, when speaking of the origins of Hindi prose in the nineteenth century, the Sabha clearly meant only Khari[*] Boli[*] Hindi.[8] The Sabha's use of the term "Hindi" expanded while moving toward the "glorious" past and contracted while moving toward the present.

Behind the Sabha's attitude lay the fact that Braj Bhasha remained the most important medium of "Hindi" poetry in large areas of north India until the 1920s. Ironically, several of the leading Braj poets lived in Banaras, some of whom joined the Sabha, and even Bharatendu Harishchandra, widely acclaimed as the father of modern Hindi, had written most of his poetry in Braj. Many members of the Sabha felt that this situation presented a great obstacle to the progress of Hindi; the language of prose and poetry ought to be the same. Instead, most prose appeared in Khari Boli Hindi and most poetry in Braj Bhasha or Awadhi. Even primary-level Hindi school books used Braj for their poetic selections, wrote Shyam Sundar Das (one of the founders of the NPS) in 1901, urging the use of Khari Boli poetry instead (Misra 1956:209). Nevertheless, Braj remained the language of poetry in Hindi school books for more than another decade (UP SVN 1913:1254).

Years earlier the opening salvo of a controversy between the advocates of Braj Bhasha and those of Khari Boli had appeared in a work entitled Khari Boli ka Padya (Khari Boli Prose) by Ayodhya Prasad

[7] Decades later Mahatma Gandhi, for a while a leading member of the Hindi Sahitya Sammelan, adopted exactly this approach in his unsuccessful attempt to bring an end to the Hindi-Urdu controversy, an approach ultimately rejected by the Sammelan.

[8] Khari Boli, the common grammatical basis of both Hindi and Urdu, is also a regional dialect of western U.P. (see n. 3).

Khatri, a resident of Bihar. Khatri published and distributed his book at his own expense to scores of well-known Hindi supporters. He hoped to persuade Urdu poets to use the Nagari script, and Hindi poets to use Khari[*] Boli[*] . He wished all concerned to meet on the common ground of Khari Boli written in the Nagari script (Misra 1956:158, 179). Although Khatri's efforts met with little success, they did serve to touch off a vigorous debate between two noted Hindi supporters in the pages of Hindustan , the province's only Hindi daily at the time.

Shridhar Pathak, the champion of Khari Boli, had earned a reputation in both of the rival literary dialects and had authored the first poem of any importance in modern Khari Boli Hindi in 1886, only a year before the publication of Khatri's book. Radha Charan Goswami, the defender of the opposing literary dialect, edited a Hindi newspaper in Brindaban in the heart of the Braj area (R. C. Shukla 1968:436, 559). He argued Khari Boli and Braj Bhasha were one language; no poetry worthy of the name had appeared in Khari Boli; Khari Boli did not allow the use of the best Hindi metrical forms; people over a wide area understood Braj; and poetry and prose could never use the same language. Most important, Goswami claimed that should poets accept Khari Boli, as Khatri had suggested, their efforts would only serve to spread Urdu. Pathak countered that Khari Boli and Braj were two languages; the future possibilities for Khari Boli poetry were great; Khari Boli did allow the use of a wide variety of metrical forms; many more people understood Khari Boli than Braj; and poetry and prose could and should use the same language. Although Pathak did not reply directly to Goswami's most important charge, unlike Khatri he neither spoke of Hindi and Urdu as the same nor excluded Braj Bhasha from the realm of Hindi poetry (Misra 1956:175–82).

Goswami had pinpointed an important issue, namely, Khari Boli poetry seemed suspect to many Hindi supporters because almost all of its recent creations were in Persianized Urdu. The real answer to Goswami's imputation appeared in the work of Mahavir Prasad Dwivedi, editor of Saraswati , the most influential periodical in the Hindi literary world in the first two decades of the twentieth century. Dwivedi used Sanskrit words and metrical forms in his own Khari Boli poetry and encouraged the same approach in those who wrote for his journal (Misra 1956:211; R. C. Shukla 1968:583). After Dwivedi, no one could seriously oppose Khari Boli Hindi poetry on the grounds that this would further the spread of Urdu. Dwivedi had succeeded in Sanskritizing the new poetic medium.

More than twenty years later the conveners of the first Hindi Sahitya Sammelan in Banaras in 1910 called on Pathak and Goswami to come forward and reiterate their previous arguments. The situation had changed, for now the question had become not whether Khari Boli

should become a medium of Hindi poetry, but rather to what extent Braj Bhasha should remain one (Misra 1956:213–24). In the second session of the Sammelan a year later in Allahabad, one advocate of Khari[*] Boli[*] had harsh words for Braj. Badrinath Bhatt, later to become professor of Hindi at Lucknow University, told his listeners that in an age when India needed men, the cloying influence of Braj had turned Indians into eunuchs. During the fifth meeting of the Sammelan in 1914, the prominent Hindi poet Maithili Sharan Gupta, a protégé of Dwivedi, spoke even blunter words. He called the supporters of Braj Bhasha enemies of India's national language, Khari Boli Hindi (Misra 1956:225, 228–29).

Part of the process of defining "Hindi," then, involved affirming the earlier literary heritage of other regional dialects in the past, but rejecting literary creations in the same dialects in the present. Because they added lustre to Hindi's past, written traditions in these dialects at least merited attention. On the other hand, because they were presumably considered too vulgar and unrefined, oral traditions, such as the biraha[*] of the Ahirs of the Bhojpuri-speaking area, received no notice. Thus the records of the NPS (for at least the first twenty years) make no mention of Bhojpuri, although its speakers constitute the great majority in Banaras and environs. Nor do they mention the reputed creator of biraha , Bihari Lal Yadav (1857–1926) (see chapter 3).

Nagari Yes, Kaithi No

Script as well as language was subject to these internecine conflicts. The Kaithi script, one of several cursive forms of Nagari used by merchant castes, led a precarious existence in the official infrastructure of British India, though surviving and even thriving in more ordinary surroundings. With a few notable exceptions, British officialdom in the province opposed the use of Kaithi in courts, offices, and schools, even though this script had much greater popularity than Nagari, especially in the eastern districts. Officials in the neighboring province of Bihar, however, displayed very different attitudes. Believing Kaithi to be the most widespread script in the province, as evidenced by the flourishing condition of the indigenous schools teaching it, the government ordered the creation of a font of Kaithi type, and by 1881 had prescribed Kaithi for primary vernacular schools. Kaithi texts soon began to appear, and the schools and courts of Bihar continued to use the script until at least 1913 (see King 1974:162–64, 166–70).

These policies met with bitter criticism from Dr. Rajendralal Mitra, a distinguished Bengali educator, in his testimony before the Hunter Education Commission. He noted that Hindi textbooks for Bihar schools printed in Nagari had previously come from Banaras, and that for every textbook Bihar could produce, the U.P. could produce a hundred.

This flow of books had kept the people of Bihar linguistically united with their fellow Hindus to the west. The use of Kaithi, on the other hand, would eventually deprive Biharis not only of the literature created by their ancestors but also of that more recently created by their kinsmen in the U.P. (Educ Comm Rpt Bengal 1884:334). Mitra spoke of Kaithi as the NPS had written about Hindustani: Kaithi threatened the linguistic and religious identity of Bihari Hindus.

Agreeing with Mitra, the NPS also rejected Nagari's rival. In its ninth year the Sabha, at the suggestion of a member, considered the question of improving Kaithi's shortcomings. After some deliberation, the Sabha declared:

In the opinion of the Sabha there are no letters more excellent than the Nagari, and in its opinion it is useful and proper for the Aryan languages of India to be written only in their Nagari letters. For this reason the Sabha cannot aid in any way in promoting the progress of Kaithi letters, nor can it display any enthusiasm for this. (NPS Ann Rpt 1903:14–15)

Although the Sabha had earlier expressed the need for a shorthand system for Hindi, it apparently never considered the possibilities of Kaithi for this (NPS Ann Rpt 1895:10; NPS Ann Rpt 1899:20; NPS Ann Rpt 1900:21–22). Moreover, the Sabha made numerous and mostly unsuccessful attempts to establish Nagari court writers in every district of the province, largely because the organization ignored the fact that almost no writers knew Nagari, especially in the eastern districts, though many knew Kaithi, and the indigenous schools teaching this script were thriving.

Contemporary sources indicate that other Hindi supporters thought Kaithi to be as illegible and ambiguous as the Urdu script, no easier or more widely used than Nagari, and unsuitable as a medium of education. Certainly Kaithi lacked the auspicious association with Sanskrit possessed by Nagari; rejecting Kaithi meant indirectly affirming Hindi's close connection with Sanskrit. To Hindi supporters, rejecting Kaithi also meant separating Hindi and Nagari from a more popular but lower level of culture. Thus, a writer in a 1900 issue of the Hindi newspaper Bharat Jiwan of Banaras argued that those Hindu trading classes who used the Muria script (another cursive form of Nagari similar to Kaithi) could not hope to better their condition until they received their education through the Nagari script (NWP&O SVN 1900:183). Moreover, a strong association existed between Kaithi and rural life: government policy in Awadh allowed, and in Bihar encouraged, the widespread use of Kaithi by patwari s or village record keepers (Educ Comm Rpt Bengal 1884:46–47; NWP&O Educ Rpt 1886– 1887:77–78; Oudh Educ Rpt 1873–1874:150).

Definition through Print:

The Growth of Publications

In 1868 several provincial governments began to issue quarterly statements of books and periodicals published or printed in the territories under their jurisdictions. Although these statements had several short-comings, especially in their earlier years, they constitute by far the most complete and detailed source for the publishing history of India during our period. According to these records, by 1914 Banaras had become the major center for Hindu-heritage languages, well ahead of Allahabad in Hindi and in Sanskrit-Hindi publications, and far ahead of any other center in Sanskrit, while Lucknow led in Islamic-heritage-language publications. Moreover, while the number of Urdu publications had grown substantially in both relative and absolute terms between 1868 and 1914, the number of Hindi publications had grown even more rapidly, so that the latter outnumbered the former by nearly three to one (see table 6.1). Up to 1900 the ratio between Hindi and Urdu publications had remained roughly constant, about fourteen or fifteen books in Hindi for every ten in Urdu. By 1914, however, the ratio had changed dramatically to nearly twenty-seven to ten, almost double the previous ratio. It is not coincidence that this literary expansion

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

accompanied an increasing articulation of the differences between Hindi and Urdu.

The British-sponsored development of the lower levels of education beginning at about mid-century played a crucial role in this expansion. The new educational system demanded hundreds of thousands of Hindi texts in the Nagari script and created thousands of career opportunities that depended on literacy in Hindi. The government's recognition of Hindi and Urdu as separate subjects in its schools as early as the 1850s, and the printing of textbooks in both the Nagari and the Urdu script, only heightened existing differences and helped to create opposing vernacular elites.

In the nearly five decades between 1868 and 1914 several other trends emerged. Publications in the classical Islamic-heritage languages of Arabic and Persian slowly diminished, with the most rapid decline occurring in the period 1900–1914. Arabic, comprising about 2–3 percent of total publications previously, dropped to 0.1 percent, while Persian publications went from about 10 percent to less than 1 percent. Hindu-heritage languages, on the other hand, after remaining on roughly equal terms with Islamic-heritage languages in the nineteenth century, showed the same striking increase as Hindi in the first years of the twentieth century, especially dual-language works in Sanskrit-Hindi, suggesting a trend toward the popularization of Sanskrit texts. (See also the discussion of the publishing history of the Awadhi Manas[*] in chapter 1.)

The geographical distribution of publication in various languages showed striking shifts during the same period. The proportion of Hindi works in the total output of the eastern part of the province remained practically constant (56–57 percent), as did the proportion of Urdu works (about 29 percent) in the west. After 1900, however, the proportion of Urdu works in the east fell to about half the former level, while that of Hindi works in the west rose to almost twice the previous level. In short, it was as if an increasing tide of Hindi works had pushed a diminishing flow of Urdu works back into the western part of the province. On the level of the vernacular elite, the differences between Hindi and Urdu had become greater. At the same time, the gap between Hindi and Urdu, on the one hand, and the regional dialects, on the other, had widened.

The Who of Hindi Supporters:

Patterns in Education and Employment

The Vernaculars and Education

In the mid-1840s the government of the N.W.P. conducted a survey of educational institutions, which presented a clear picture of the social

backgrounds of students and teachers in Persian, Hindi, Arabic, and Sanskrit schools in many districts. The distribution of students and teachers in the Persian and Hindi schools (the great majority of the total) of Agra district fairly represented the general situation in other districts. Muslims and Kayasths composed the great majority of teachers and students of Persian, and Brahmins, Baniyas, and Rajputs, of Hindi. Moreover, all but a handful of Muslims studied Persian, while most Hindus (with the notable exception of Kayasths) studied Hindi (NWP Educ Rpt 1844–1845:Appendix I).

Another aspect of language study patterns appears in statistics for government schools in 1859–60. In the western part of the province students learning Islamic-heritage languages were a slight majority, while in the central and eastern parts those learning Hindu-heritage languages were large majorities (NWP Educ Rpt 1859–1860:Appendix A, 2–62). Similar figures for Awadh in 1869 show a pattern very close to that of the western N.W.P., with slightly more than half the students learning Islamic-heritage languages, a little more than a third, Hindu-heritage languages, and the remainder, English (Oudh Educ Rpt 1868–1869:Appendix A). In both Awadh and the N.W.P. another pattern appeared in education statistics during this period: the higher the level of education, the greater the proportion of students taking Islamic-heritage languages and English, and the smaller the proportion taking Hindu-heritage languages (see King 1974:84–91).

When we put these patterns together, a picture emerges which correlates quite well with the distribution of Hindi and Urdu publications discussed above: Hindi in a subordinate position in government institutions, contrasted with Urdu well entrenched in the higher reaches of education and administration; Hindi supported by castes associated with Sanskrit learning and resistance to Muslim rule in the past, versus Urdu upheld by Muslims and those Hindu castes (chiefly Kayasths) with a vested interest in Indo-Persian culture; Hindi whose stronghold lay in the eastern part of the province where the Hindu merchant tradition was more powerful vis-à-vis Urdu, whose strength lay in Awadh and the western part of the province where the Indo-Persian service tradition was more dominant (Bayly 1983); and finally, Hindi and Urdu studied almost entirely by high-caste Hindus and Muslims.

The Vernaculars and Employment

In 1877 the provincial government first prescribed a successful performance in either the Middle Class Vernacular or the Middle Class Anglo-Vernacular Examination as a qualification for government service. By the mid-1880s the sizable increase in the numbers of candidates showed that the order had begun to take effect. Lists of those

passing the examinations were sent to each collector or Deputy Commissioner, and in many districts vacancies were filled from them. By the late 1880s these examinations had come to be the educational event of greatest interest to many hopefuls for government service. Their popularity began to wane toward the end of the century, however, as graduates with higher qualifications offered increasing competition. The statistics for these two examinations plainly show the dominance of certain castes, especially Kayasths, in the struggle for government service. They also show that the chief rivals of the Kayasths and Muslims were high-caste Hindus, namely, Brahmins, Rajputs, Khatris, and Baniyas (NWP&O Educ Rpt 1885–1886:Orders of Government, 6; NWP&O Educ Rpt 1886–1887:15–17, 19; King 1974:186–94).

The 1877 order had a significant effect on the numbers of candidates opting to study one or the other of the two vernaculars. In the twenty-year period between 1875 and 1895 the proportions of candidates taking Hindi and Urdu reversed themselves. In the mid-1870s Hindi candidates accounted for more than three-quarters of those taking the examinations; by 1887 Urdu candidates made up more than three-quarters of the total, and this ratio remained nearly the same for the rest of the century (Malaviya 1897:31). The reason for this shift was clear: as a result of the 1877 orders, the candidates chiefly valued the examinations as a means to government service, and naturally preferred to take them in the vernacular language that dominated in courts and offices.

Let us imagine a picture based on the preceding data. A pair of gates labeled Vernacular Middle and Anglo-Vernacular Middle Examinations stands before us. Through them pours a crowd of thousands, moving in the direction of more distant gates. A small portion of the crowd, mainly Muslims and Kayasths, succeeds in passing through one of these more distant gates, labeled Subordinate Judicial and Executive Services, but many others are turned aside. Among these, numbers of Brahmins, Rajputs, Khatris, and Baniyas, as well as a few Muslims, succeed in crossing the portals of a large gate labeled Educational Department. Others, among them many Muslims, manage to enter a smaller gate labeled Police Department. Some of the remaining crowd enter through other, smaller gates, but many fail to pass through any gate and straggle off into the surrounding countryside. Here live millions unacquainted with either Sanskritized Hindi or Persianized Urdu who come from the lower levels of Hindu and Muslim society—Ahirs, Chamars, Bhangis, and many others.

This fanciful portrait is meant to suggest that many non-Kayasth Hindus found that their best hope for government service lay in the newer Educational Department rather than in the older, more presti-

gious, and more remunerative Revenue or Judicial Departments. From the ranks of such Hindus came many leaders of the Hindi movement. The three founders of the NPS, for example, included a Brahmin, a Rajput, and a Khatri; all three made their careers in education—two in government service, and one in both government and private service. Our portrait also suggests that the great majority of the population, the repository of popular culture, did not share the concerns of the vernacular elite.

Yet another aspect of the relationship between education, language, and employment appeared in the results of an investigation ordered by the provincial lieutenant-governor in May 1900, a month after he had issued a resolution ostensibly granting equal status to the two vernacular languages and scripts. This investigation, which included the courts and offices of the Judicial and Revenue Departments from the highest to the lowest level in each district, aimed at determining the respective numbers of Hindu and Muslim clerks familiar with Hindi or Urdu or both (NWP&O Gen Admin Progs October 1900:111, 119, 122–24).

The results showed that most Hindus knew at least some Hindi, and even more knew at least some Urdu. On the other hand, fewer than half of the Muslims knew at least some Hindi, while all knew at least some Urdu. To put matters differently, almost all the Hindus knew Urdu well, and the majority knew Hindi well too. While almost all the Muslims knew Urdu well, only a small minority knew Hindi well. Contemporary observers suggested with good reason that the results were very likely skewed in favor of Hindi. Even so, the investigation clearly indicated that Muslims had a strong vested interest in Urdu, the dominant language of the courts and offices, while Hindus, though rivaling Muslims in Urdu, could easily turn to Hindi, where they far outstripped Muslims. In sum, Muslims stood to lose much more from any change than did Hindus. For the thousands of Hindus and Muslims educated in the vernaculars—that is, those who constituted the vernacular elite—language identity and economic well-being were bound together inseparably, a fact that intensified the rivalry between supporters of Hindi and Urdu.

The Role of Voluntary Organizations:

The Nagari Pracharini Sabha

If Pandit Gauri Datta had expressed himself visually, his play might have taken the form of the picture that appeared in the November 1902 issue of Saraswati (R. K. Das 1902:359: see figure 14). On the left stood a Muslim prostitute, decked out in all the finery of her profession. On the right, facing her rival, sat a Hindu matron, modestly

clothed in an ordinary sari. The caption "Hindi-Urdu" and the verses below made it clear that on the left stood Urdu personified and on the right sat Hindi. The author of the verses was Radha Krishna Das, a member of one of the great merchant families of Banaras, a relative of Bharatendu Harishchandra, and the first president of the Nagari[*] Pracharini[*] Sabha[*] of Banaras.

As the nexus of relationships embodied in the picture suggests, the Sabha both reflected and contributed to the process of change discussed above. Founded in 1893 by schoolboys of Queen's College in Banaras, the Sabha soon acquired influential patrons such as Madan Mohan Malaviya, played the leading role in mobilizing support for the resolution of May 1900, gave prizes for Nagari handwriting in schools, granted awards for Hindi literature, carried out extensive searches for old Hindi manuscripts and published the results, started two influential journals (the Nagari Pracharini Patrika and Saraswati ), attracted a membership of many hundreds, received donations of thousands of rupees, founded the Hindi Sahitya Sammelan of Allahabad, constructed a major headquarters building, published many important works (including grammars and dictionaries), and lobbied the provincial Text Book Committee and other government organizations for Nagari and Hindi (see King 1974:243–377, 455–79). Through all these activities, the Sabha played the leading role in affirming and defining Hindi during our period, a Hindi separate and distinct from Urdu, other literary dialects, Hindustani, and the popular culture of oral tradition.

The social and geographic origins of the early membership of the Sabha, not surprisingly, showed patterns that strongly correlated with the patterns of publication, education, and employment we have already examined. Brahmins, Khatris, Rajputs, and Baniyas[*] (mainly Agarwals) accounted for more than two thirds of the total membership of 84 in 1894. In the same year provincial residents composed 80 percent of the membership, and residents of Banaras 56 percent. The eastern portion of the province provided 68 percent of the membership, Awadh and the western portion only 6 percent each. The remainder of the membership came from Rajasthan, Punjab, the Central Provinces and Central India, Bihar, and Bengal (King 1974:251–68).

By 1914, the peak year before a prolonged decline in membership, the proportions had shifted. The province had dropped to 64 percent and Banaras to 16 percent of the total of 1,368 members, though the leadership remained firmly in the hands of the same Banaras castes. While the share of the eastern portion of the province fell to about 33 percent, that of the western part rose to 20 percent, and that of Awadh to 12 percent, mostly in the two or three years before 1914. Rajasthan, the Central Provinces and Central India, and Bihar made up 23 per-

cent. The Sabha remained an almost entirely north India and Hindu organization throughout our period: the first of a handful of south Indians joined in 1908, and only tiny numbers of Muslims ever became members (King 1974:445–51).

While much of the financial support for the Sabha came from membership donations and the sale of publications, especially school textbooks, a significant portion came from large donors, many of whom were princes. In the first thirty years the organization's twenty largest donors contributed close to Rs. 100,000, or approximately 30 percent of the total income. Twelve of these donors were princes, seven of whom became official patrons of the Sabha, namely, the Maharajas of Gwalior, Rewah, Baroda, Bikaner, Chatrapur, Alwar, and Banaras (King 1974:452–54, 456–59).

Whereas the Sabha's first decade brought significant successes in both political and literary endeavors, the second decade saw continuing progress in the latter but little or no advance in the former. From about 1914 on, the Sabha devoted most of its energies and funds to literary efforts and turned away from political activities. So politically conservative did the organization become that the government even allowed the Sabha to keep proscribed books. In the decades to come, not the Sabha but the Hindi Sahitya Sammelan played the preeminent political role on both the provincial and the national level in the promotion of Hindi and the Nagari script.[9] The Sabha remained content to embellish Hindi literature.

Conclusion:

New Identities—The Terminus Ad Quem

The picture in Saraswati provides a convenient departure point for summarizing, analyzing, and speculating about what we have learned of the Hindi movement. By the early twentieth century, as the distance between the two women suggests, the Indo-Persian and Hindu cultures had become separate clusters of symbols for many members of what we have called the vernacular elite. From the more extreme Hindu view-point, the two figures stood for virtue versus vice; from the more extreme Muslim viewpoint, for barbarism versus refinement (see Rahmat-Ullah 1900). As one scholar of north India has suggested, various symbols of communal identity gradually clustered around the master symbol of religion in a process designated as "multi-symbol congruence" (Brass 1974).

We need not restrict ourselves to models from Western sources to analyze the Hindi movement, however, for the process of linguistic

[9] The membership of the NPS and the HSS certainly partially overlapped in the early years of the latter, although how much I do not know. The leadership, however, soon became entirely separate and remained so for decades.

"purification" has a venerable social and cultural history in India. Just as certain standards for social behavior, especially for those castes wishing to elevate their position in the hierarchy, have been embodied in Brahmins for many centuries, so standards for language behavior have resided in Sanskrit, whose very name means "perfected." Thus we can explain much of the Hindi movement as a process of "Sanskritization" in which the excellence of a language was judged by the degree to which it incorporated the standards of Sanskrit. At the same time, we must not overlook the influence of English, which provided a not necessarily antithetical model of a modern language. The supporters of Hindi could choose or reject, and they did; roman letters proved unacceptable, while dictionaries of scientific terms were deemed acceptable.

Through the processes of separation and rejection Hindi supporters determined what Hindi was not and what Hindi should not be . Through the more positive processes of affirmation and definition they decided what Hindi was and what it should be . Hindi was certainly not Urdu (separation) nor should it be (rejection). On the other hand, Hindi had descended from Sanskrit (definition), something good for religious and cultural reasons (affirmation). These admittedly imprecise terms suggest the active approach of the vernacular elite to the creation of a new language style, what we might tentatively call the Sanskritization of Khari[*] Boli[*] (the common grammatical base of both Hindi and Urdu). From this viewpoint we can argue that the rejection of Hindustani, Kaithi, and popular oral traditions rested primarily on their relatively "impure" natures as compared to a shuddh (pure) Hindi. In the cases of Braj Bhasha and Awadhi, however, such an explanation does not suffice. Here more practical reasons seem to have prevailed: though both acted as bearers of a glorious literary tradition and parts of Hindi's past, neither possessed the necessary characteristics for a potential national language. Only Sanskritized Hindi, sharing the same grammatical base as the already widespread Urdu, had both the necessary purity and practicality.

While the vernacular elite played an active, not passive, role in the Sanskritization of Khari Boli, they forged Sanskritized Hindi within arenas—the educational system, the press, the publishing industry, voluntary associations, and the government itself—largely introduced through British rule. This external framework displayed fundamental ambiguities, however: thus, a close study of the period reveals that British officials authored language policies with massive contradictions (see, for example, King 1974:383–93) which exacerbated the very conflict they decried and left considerable room for the vernacular elite to maneuver.

By the eve of World War I, then, a class (the Hindi vernacular elite) had appeared in north India, especially in eastern U.P., whose commu-

nity identity centered on shuddh Hindi, Hinduism, and an urban alliance of service and merchant interests. The harmonious working relationship between two leading members of the Sabha, Radha Krishna Das, merchant, and Shyam Sundar Das, educator, beautifully illustrates this alliance. The intensity of the struggle with the Urdu vernacular elite in the province expanded to the national level in the twentieth century. The emphasis on the purity of Hindi widened the gap between Hindi and Urdu as well as between elite and popular culture. The final result came after Independence, when Hindi became one of the two official languages of India, and the only official language of the U.P., thus at last fulfilling the judgment of Maharaja Righteous-Rule in Pandit Gauri Datta's svang[*] . Truly, Queen Nagari, born in Sanskrit-rich Banaras, ruled again.