Introduction to Part 2—

Identity and Constructions of Community in Banaras

The following two chapters focus on local communities in Banaras. Although approaching the subject from different vantage points, they both address a process central to South Asian social history: the formation of collectivities, through the various affiliations by which Banarsis identified themselves, and the potential inherent in such formation for popular support of political, religious, and social movements. The constituent elements of this process were a series of interrelated choices made by individuals: on place of residence, means of livelihood, forms of leisure, and participation in ceremonial, ritual, and other collective activities (see map 5).

Through such choices individuals defined their own identities. Taken together, these individual actions also constituted what we may call constructions of community ("construction" emphasizes the active and largely self-conscious involvement of participants in the process). That is, in the aggregate, such actions delineated the outlines of a community by underscoring the particular affinities shared by members of the group. Given the wide variety of affinities from which urban residents might choose, such constructions could vary from moment to moment or context to context, depending on circumstances that changed often and regularly: community identity was neither static nor marked by a lineal development. Moreover, particularly in moments of conflict, residents chose to identify with particular groups often in contradistinction to an "other"; this, too, could change over time.

Conceptualization of the north Indian city as a congeries of communities whose interaction constituted the basic line of historical narrative not only is the underlying premise of this volume but also suggests the way residents of Banaras often perceived themselves. A recent biraha[*] song text collected by Marcus, for instance, chronicles the events relat-

ing to a temple theft in Banaras. Public outrage, the lyrics tell us, was expressed symbolically through a series of parades, each one representing a particular "community" in Banaras (and we might note the differing bases for identity implied by this list):

Seven big parades went and demonstrated at the chauk police station.

One day the parade consisted only of women, only of women, only of women. . . .

The deaf and dumb, lepers and beggars took out a parade; political leaders organized their parade;

Astrologers, students, and sadhus went ahead, and demonstrated at the chauk police station.[1]

The conscious choices of community affiliation made by participants thus provide points of entrée for scholars interested in the shared values and organizing principles embraced by constructed communities. These essays use as entrée variations of local identity, examining the process at its most basic units, in the small communities of occupation, neighborhood, and local belief system. There were other ways of constructing communities as well—identities that reached beyond these most localized forms. Several of these have been touched on in other chapters in this volume. Most notable, perhaps, were those of gender and that intriguingly prevalent form of association, the akhara[*] . In part to encourage further research on such subjects, we summarize briefly here what we know of these topics, before turning to neighborhood, work, and leisure—the vantage points used to view community delineation in this part.

Organizing Expressions of Identity

Generally speaking, the literature has discussed women in South Asia from a variety of viewpoints, but has not yet dealt adequately with the special place for women in Indian popular culture activities.[2] Indeed, we may suspect that, once sufficient research has been done, the "popular culture" of women may well constitute a rather different world from that presented in this volume. As Narayana Rao recently argued, this separation seems to result, in part at least, from the different emphases and worldviews of women (N. Rao 1988). Discussing the "domestic" versions of stories from the Ramayana presented in the women's quarters in South India, Rao noted that both the sections of

the narrative that are selected out for retelling, and the interpretations of behavior implicitly conveyed through these oral presentations, differ strikingly from the public (male?) versions discussed in this volume. In the women's version the heroes are not larger than life: all demonstrate typically human character flaws (illustrated by Rao in a particularly revealing scenario in which Varuna's laughter is taken by each listener as a judgment on his personal shortcomings). And in contrast to the public presentations of the epic where the action ranges across the subcontinent, the women's Ramayana, not surprisingly, presents an enclosed world both loving and tension-filled, much resembling the domestic structures of an extended family.

Another important contributor to the separation of women's popular culture from that studied here will be the fact that, in many cases, the activities occurring in public spaces, and at late-night hours, were considered inappropriate venues for women. Women did not attend the performances of street theatre described in chapter 2. They seldom constituted more than a small part of the audience for biraha[*] performances, and then only appeared in the early-morning period, when they could stop to listen on the way back from their walks to the open areas of the city for defecating. Devotion, however, lent a legitimacy to public activities, serving as a rationale for women's participation. They figured largely in temple shringar s[*] and among Bir[*] worshippers. Lutgendorf notes, too, that they not only swelled the audiences for katha[*] (in any case, a safer venue because staged "indoors"), but even figured occasionally among the exegetes.

As the biraha lyric suggests, however, women did, sometimes, even publicly mobilize to present their opinions. After marching to the chauk police station, this song goes on, they symbolically enacted their displeasure with police inaction, by presenting to the police a tray with women's "petticoats" and jewelry, thus suggesting that—since they were so ineffectual in the public world—the police might as well take on women's roles and dress.

The implications in Hess's work on Ramlila[*] , too, suggests that women did have certain, albeit specialized, places in public activity. "A large majority of the audience [is made up of] men, but many women come in the course of the month. Usually an informal 'women's section' takes shape. Women are not strictly required to stay there, but most of them do, along with the children they often have in tow" (Hess 1987:3). Most striking, many of the women observing the Ramnagar Ramlila do so at the side of the actor representing Sita[*] . During her exile, they remain with her in a remote part of the city, removed from the main drama being enacted elsewhere, for days on end (Schechner and Hess 1977:55). Clearly this reformulation for women of the very nature of public spaces, and of the nature of participation in collective activities,

will require much more work before we can understand the meaning of this specialized world of women within the urban environment.

Similarly, no systematic discussion and analysis of the structure or functioning of akhara s[*] has yet been made, although analyses specific to music and medicine point the way (see Neuman 1980; B. Metcalf 1986), buttressed by the implications of work on sannyasis and courtesans.[3] The essays in this volume suggest an outline that, while still shadowy, conveys some of the significance of this organizational form. Based on a recruitment of members who joined voluntarily, akhara s nevertheless expressed connections between members in fictive kinship and familial terms. They relied as well on variations of the guru-chela relationship to connect teachers/leaders to members/followers.

The akhara[*] form emerges as the basic unit for a number of very different activities, including "physical culture" clubs, medicine, and even the organizational structure used by mendicants, but preeminently for the organization of cultural performances—particularly in music (both classical and folk), theatre, and the mastery of courtesans over poetry, musical instruments, singing, and dancing. (For a discussion of the timing of the elaboration of this organizational form, see the introduction to Part 1.) Of these, we are most familiar with akhara s in the form of physical culture clubs, which encouraged athletic prowess in wrestling, sword and stick performances, and the like (e.g., Chandavarkar 1981; and examples cited in Chaudhuri 1951).[4] These clubs often performed during ceremonies and processions; they also could form the basis of marauding gangs during communal clashes.[5]

Akhara s[*] fulfilled other significant functions as well. The discipline of of the guru-chela relationship proved important, as chapter 3 suggests, as a method not only for perpetuating but also for controlling quality as well as the dissemination of material. It is not irrelevant that biraha[*] performers could not sing materials created by a rival akhara , or have their materials printed. Beyond neighborhood, akhara s provided a basic unit for mobilizing for collective action of various kinds; depending

on the eclecticism of the membership (some akhara s[*] were more heterogeneous than others, drawing members from a broader social base and geographic area), akhara s represented a potentially diverse and distinctly voluntary form of social organization. They may even, as one scholar has recently suggested, have proved particularly important as an alternative form of society for groups like women and sadhus, thus providing structures to control and use resources, as well as refuge from the world dominated by traditional social structures (Oldenberg 1987). In any case, local perceptions of such akhara s awarded them great significance. A recent essay discussing the "histories" written by its residents of an eastern U.P. qasba[*] , for instance, shows us that two of the thirteen events deemed "important" by one author involved disputes between teams of wrestlers (G. Pandey 1984:244).

If akhara s provide an important point of entrée for discussing the nexus of various cultural activities and local social organization, neighborhood provides another important avenue of analysis. Approaching the subject from one vantage point within the neighborhood, Coccari examines the muhalla[*] as a base for forming and expressing identity through worship of particular neighborhood Birs[*] . Her discussion of local deities also suggests the process, discussed by Marcus as well, by which activities originating with one caste or subcaste (in this case, Ahirs or Yadavs[*] ) become generalized to lower-class culture, thus incorporating ever-larger numbers of people. Coccari and Kumar note two important characteristics of this expansion: first, the sheer number of activities and occasions have been expanding significantly in the last decade or two. Implied by this increased activity is an elaborated and inclusive lower-class culture that gradually is laying claim to the public spaces of north Indian cities. Second, expansion of such activities has tended to take forms, such as the worship of neighborhood deities, that elicit little orthodox or upper-caste opposition. Thus it appears that a discrete world may be in the process of being fashioned, one that underscores by its very separateness the differences now perceived between upper- and lower-caste urban culture. A third point might be noted as well: the dispersion of this lower-caste urban culture through the movement to industrial centers of up-country workers, particularly weavers. Indeed, one of the more striking aspects of the work of Chandavakar (1981) on Bombay millworkers' neighborhoods, and Chakrabarty (1976) on the popular culture of Calcutta bastis[*] , is the extent to which collective ceremonial activities resemble those the mill-workers left behind them in U.P.

This would present a very different pattern from that prevalent in Banaras throughout the nineteenth and into the early twentieth century, a phenomenon examined in greater detail in Part 3. Yet there are

still, at present, some indicators of ties to upper-caste values (or, perhaps more accurately, to values shared by upper and lower castes), for these local forms of worship focus on bir[*] figures that combine warrior and saintly paradigms—a combination historically important in Banaras through the dominance of the Gosains, the group of soldier-trader mendicants discussed in the introductory essay on political economy. The meaning inherent in such symbolic public activity is, however, quite complex. Popular support, for instance, may be inferred from the wholesale audience participation by the lower castes in the Ramnagar Ramlila[*] . We noted earlier Hess's point that the messages of the Ramcharitmanas[*] are multistranded, with inherent tensions between egalitarian and hierarchical values. Such complexities doubtless enable its participants to pick and choose those they support. How this works is suggested by a conversation Hess reported with Mahesh Prasad Yadav, "one of the most deeply committed, long-time devotées at the Ramnagar Ramlila, and a member of the Yadav[*] or milkman caste (associated with the Shudra varna , though he was prosperous and highly respected)." She asked him what he thought of the Manas[*] line, "A drum, a peasant, a Shudra, an animal, a woman—all these are fit to be beaten." He replied:

I don't believe that. I am a Yadav. When people say [using an honorific], "Panditji, Panditji" to me, I say, "Listen brother, don't call me Panditji. I am a Yadav." . . . Look: karama pradhana[*]vishva kari rakha[*] [the world is based on the law of actions]—this is in the Ramayana . It is not written jati[*]pradhana vishva kari rakha [the world is based on the law of caste]. Write it down, in this one verse is all meaning. Not jati pradhana . (Hess 1987:25)

This devotée, then, simply chose from the larger whole which verses he would credit as authentic. We may assume that other participants do much the same, basing their selections on the insights they have gained by their experiences as members of particular groups with certain kinds of identities.

Hess's Yadav informant makes it clear that, in this context, his caste (jati ) identity as Yadav was important (and thus that he should not be given titles inappropriate to his station in life). So too, however, were his actions. Many of these actions would have been organized through the devotional, recreational, occupational, and residential structures of urban life. Residence—neighborhood—meant many things. In the Banaras of these essays, residence patterns in many muhalla s[*] (particularly of artisan and service castes) tended to be coterminous with occupation; similarly, caste or class affinities may have substituted as a shared basis for residence for those among the elite. Primarily because of migration patterns into a city, muhalla[ *] residence patterns also often, but not entirely, coincided with extended kinship patterns, regional and linguistic

affinities, and even natal village origins. Shared religious beliefs often followed from these other affinities.

Although in the eighteenth century the boundaries of a muhalla[*] could be traced by the actual construction pattern—that is, a muhalla coincided with a single, coterminous building (Blake 1974)—the concept evolved so that even this basic attribute could not define the functional boundaries of a muhalla later on. Instead, the boundaries of a muhalla were often perceptual, unofficial: the neighborhood did not correspond to any official unit such as "ward." At the same time, however, muhalla s[*] did have a formal role in self-government, with spokesmen pronouncing their decisions affecting taxation and organizing themselves for collective activities such as processions and neighborhood-based religious observances. Muhalla s[*] had unofficial roles as well, often channeling competition and conflict along these lines of identity. One Muslim weaver muhalla in Banaras, for instance, generally saw itself in opposition to another located elsewhere in the city: in this case, their shared occupation functioned as an avenue to channel competition—a competition in which specific neighborhood identity, instead, provided the basis for fellow-feeling (see chapter 5).

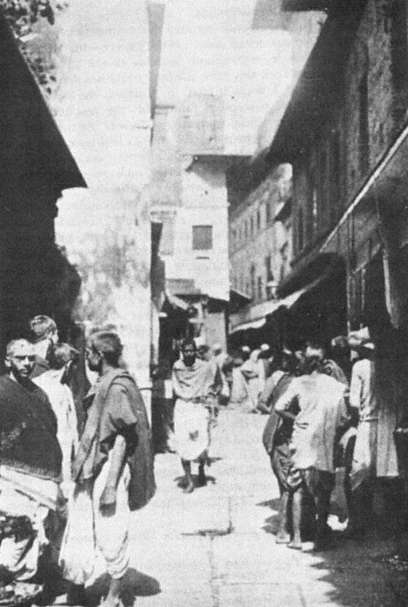

Expression of a coherent and self-conscious identity at the neighborhood level emerged particularly in leisure-time activities and in collective religious observances, as chapter 4 suggests.[6] Much associational activity featured neighborhood residents as "audience," and in connection with this role, the public space of the muhalla figured prominently. As is noted by Chandavakar, "Street life imparted its momentum to leisure and politics as well; the working classes actively organized on the street. . . . Thus, street entertainers or the more 'organized' tamasha players constituted the working man's theatre. The street corner offered a meeting place. Liquor shops frequently drew their customers[,] and gymnasiums [i.e., akhara s[*] ] their members[,] from particular neighborhoods."[7] Indeed, both Chandavakar and N. Kumar (1984) have documented the extent to which recreation for lower-class males frequently consisted simply of "roaming" the streets of the muhalla (see fig. 9).

Ritual and neighborhood identity were closely connected as well.

Fig. 9

A neighborhood street in Banaras in about 1910. C. Phillips Cape, Benares, the

Stronghold of Hinduism (Boston: Gorham Press).

While some activities remained confined within the muhalla s[*] and made important statements for their occupants, many were extra-muhalla[*] in nature. These larger collective activities depended on muhalla contributions in money and manpower; examples of both types of ritual activities are examined in chapters 4 and 5.

The World of Work

Nita Kumar, too, uses a local focus to trace the overlapping identities invoked, in varying circumstances, by Banarsi weavers who are also Muslims: at what moments, she asks, do they perceive their preeminent community to be (respectively) that of weavers? that of Muslims? that of Banarsis? While Kumar and Freitag (see Introduction and Part 3) may not agree completely on the nature or context of this process of identity formation, they both recognize the centrality of the process for the social history of Banaras. From their work, in any case, it is possible to trace in outline, at least, the relationship of a particular lower-class group to an urban place and its culture, and to begin to delineate the process of identity formation and construction of community within this central-place idiom.

In a very illuminating contribution that could not be included here, American artist Emily DuBois detailed for the contributors the material world of the weavers that she encountered when she researched brocade weaving in Banaras in 1981.[8] Beginning with a historical summary of the changing patterns of courtly consumption, she showed us the implications of this form of patronage for the survival and relative security of Banarsi artisans. In particular, her discussion of changing styles (influenced primarily by courtly culture), and of the vicissitudes of the changing economy of weaving (affected by larger technical and economic trends) demonstrates the connections between the everyday lives of weavers and the imperial order. Indeed, the extraordinary longevity of the appeal of Banarsi brocade may go far to explain the social stability and integration of Banaras's weavers in the city's political economy. Further, we may see certain parallels in her discussion of changing patronage with the history traced in Part 1 of patronage for performance artists. That is, there is a very similar movement from the central role played by the Mughals to the importance of the successor-

state courtly culture for survival of the handloom industry; from the consistent consumption patterns of Indian brides over several centuries to the new, self-conscious efforts of the independent Indian government to preserve and extend the art and skills of handloom weavers: patronage has provided the key element in the survival of the Banarsi style of weaving. Even for vast numbers of weavers who remain unaware of the role played now by the Weavers' Service Centers (N. Kumar 1984), the impact of the government on their livelihood has been far-reaching, as it has expanded foreign and domestic markets and trained personnel to manage the marketing of handloomed cloth.

Equally important has been the Banarsi context in which handloomed cloth is produced. The independence enjoyed by the Muslim weavers of Banaras has fostered a very special and individual sense of self among these weavers, who take great pride in their "freedom" and control over their work conditions, particularly, in the fact that they have been able to continue to work in their homes or in the relatively small karkhana s[*] that characterize the workplace. The description of the nature of the work provided by DuBois conveyed the degree to which weavers do control their work time and rhythm; but it also suggests the interdependent relationships they have with zari (gold-wrapped thread) producers, their women who wind the silk thread, and especially the merchants and middlemen who supply them with credit, yarn, some of the marketing outlets, and even many of the designs they use. Only by understanding this complex of working conditions can we fully appreciate the world of Banaras weavers.

DuBois's detailed discussion of the physical world and procedures of weaving provides us with a richer understanding of what identification as "weaver" meant: it enables us to connect elements of identity to the material processes in which weavers are involved daily. For that reason, we have included here the section of her essay describing that world as she was permitted to enter it (which nicely complements the description provided by Kumar in Chapter 5):

There are several areas in Banaras where brocade weavers traditionally live and work. On the northern edge of the city is a neighborhood called Rasulpura, not far from the Weavers' Service Centre in Chowkaghat. Quite different in character from the central city, Rasulpura has the character of a small Muslim village. The area lies a little apart. A dry road leads past a mosque, an expanse of open ground where men prepare the warps for their looms, then into the narrow streets and closely walled houses. In a courtyard one man sets the hooks on a jacquard box while in the balcony above several women are winding silk threads onto reels. An open window reveals a cool dark room filled completely with looms. It appears that in almost every home people are making the brocades for which this city is famous.

The loom traditional to Banaras brocade weaving is the pitloom, which is still used today. A hollow is dug into the dirt floor underneath the front of the loom. The weaver sits on a bench at floor level with his feet in the pit containing the treadles. The harnesses and other hanging parts are suspended from the ceiling, while the horizontally stretched parts are attached either to the walls or to posts built into the floor. Thus the entire room becomes the loom. In brocade weaving, two men work together, the weaver at the front of the loom and the helper or drawboy on a plank placed above the warp at the back of the loom. The jacquard and jala[*] mechanisms are attached behind the two or more standard harnesses used to weave the ground cloth.

While brocade may be woven on looms of various types, it is the jala drawloom system that makes Banaras brocade unique. The character of the design elements and their layout within the boundaries of the fabric which so readily define a sari as Banarsi, are in great part a function of the capabilities of the jala . Even when used in conjunction with the jacquard, jala is preferable for smaller motifs with 2 repeats. It is easier to design a naqsha[*] than to punch jacquard cards, easier to set up the jala and to store it, and in some ways it allows for more flexibility of design. The weaver can select the sequence (forward or reverse) and therefore the direction of the motif, and can choose to weave some or all of the repeats of the motif on the fabric. (For details on the weaving processes, see DuBois 1986.)

One home-based workshop in Rasulpura is operated by some eighty-five members of an extended family, supervised by the master weaver Anwar Ahmed Ansari, a man in his fifties who learned weaving within the family. What makes him different from most master weavers is that he received advanced training at the Weavers' Service Centre and continues to maintain business connections there.[9] As in all the weavers' homes, the weaving, dyeing and other tasks done by the men are all carried out in several loom rooms and open courtyards at ground level, while upstairs the women work at silk reeling and fabric finishing as part of their daily housework. There are eleven children from the family presently learning weaving as well as more than twenty related operations. The karkhana[*] also hires weavers from outside the family, some Muslim and some Hindu, and sometimes employs a designer/weaver who was trained at the Weavers' Service Centre. The master weaver owns a collection of brocade designs from outside sources. In addition to weaving brocade saris and yardage, this workshop occasionally takes on projects such as weaving jute and wool wall hangings developed through the Weavers' Service Centre with contemporary designs intended for export. Orders for brocades may also come through the Weavers' Service Centre as well as from private commercial sources.

According to Anwar Ahmed Ansari, two workers can produce a sari in about a week. The work is somewhat seasonal, particularly for wedding

saris, but generally steady. Weaving may be done to fill specific orders or on speculation. After the sari is removed from the loom it may be given to other workers who press, size and polish it by machine rolling. Often the shopkeepers prefer to keep unfinished saris in stock, which are only polished after being purchased by the customer.

We might note that the weavers' connections to the larger world through their weaving includes more than these merchants and the producers of the materials they use. In Banaras today, designs, too, come from various sources. Master weavers may have collections of old designs or may purchase new designs from traditionally trained designers or from merchants or middlemen. The government-sponsored Weavers' Service Centre in Banaras is another important source.

Since 1952 with the constitution of the All India Handloom Board, the central government of independent India has taken an active role in revitalizing the handloom industry in India, building on the colonial government's experiments of the 1930s and 1940s. Members of the Handloom Board represent various interests including handloom weavers, exporters, cooperative banks, mill industry and central and state governments, with programs administered by the Office of the Development Commissioner under the Ministry of Industry. The programs are geared primarily toward weaving of simple cotton cloth by rural, relatively unskilled workers, the largest cottage industry in India second only to agriculture in the village economy. By contrast, Banaras brocades have always been woven by highly skilled artisans and served by specialized markets, and so were not as affected by the competition from industrialized Britain nor targeted for development by the Indian government.

While supportive schemes of the All India Handloom Board—as weavers' cooperatives, direct subsidies on production and sales, and setting up of pre- and post-loom facilities—did not directly affect brocade weaving, the establishment of the Weavers' Service Centre in Banaras has made a profound and subtle difference. Set up in 1956 by the All India Handloom Board, there are presently twenty-one Weavers' Service Centres throughout India, including the one in Banaras. The Weavers' Service Centres contain three sections: artist studio, dye lab, and weaving section; the work done in each has made technical differences in the physical processes and end results of the weaving. Once again, it reflects the impact on weavers of governmental patronage, this time suggesting an interplay between a "national" culture, and the long-lived local one of brocade production.

These discussions of neighborhood, leisure, and work patterns, then, enable us to begin sorting out upper and lower caste/class values, belief systems, and behavior in a north Indian urban setting. Within the range of approaches and subject matter presented in this part are embedded a number of important issues discussed throughout the volume. Taken together, the essays are richly suggestive of the ways in

which Banarsis use identity to mobilize for work and leisure.[10] Such mobilization, in particular, is an important subject for this volume as it demonstrates most directly the connections between popular culture and the power relationships that affected larger events in the history of Banaras and colonial South Asia. The processes and value systems expressed in the culture shared at this local level constitute building blocks contributing to the events we think of as "history," including popular values and assumptions; ways of expressing as well as solidifying constructions of community; the role of the neighborhood and other voluntary associational activity in mobilizing Banarsis for action. These building blocks will recur in Part 3, where their connections are traced to broader issues and contexts.