5. The Discipline of the Wrestler’s Body

In the dream of rational control over corporeal existence, the picture looms of growing medicalization and technology to such an extent that the body is controlled, not by nature this time, but by our own inventions.

When thousands of people stop to look at a famous wrestler, then one may say that the character of the wrestler calls out; it beckons. So what is this character? A wrestler has a majestic body. He has strength. He has stamina, skill, experience, and, if he is educated and well read, then he has knowledge and wisdom. He has humility and is well mannered. He is skilled . . . and who knows what all else. Any number of these traits define his character, and as long as they are maintained they will be the reason for the wrestler’s fame. But most of all a wrestler’s character is defined by his strength. . . . Character is fostered by strength and, in turn, strength is the aura of character. A wrestler builds his character through his own efforts; he reaps what he sows. Celibacy is the paramount means by which a wrestler establishes his character. He is a disciple of celibacy.

| • | • | • |

Introduction

In this chapter I will outline in detail the regimens of exercise, diet, and self-control that structure the wrestler’s body. Careful attention will be given to the precise mechanics of physical training which develop and shape the individual body in terms of somatic ideals. Before embarking on this project, however, I must consider the nature of the relationship of the individual body to these ideals.

The notion of a fit and healthy body being an ideological construct is a fairly common theme in discourses of nationalism and power (Gallagher 1986; Jennifer Hargreaves 1982; John Hargreaves 1986; Hoberman 1984). But while the equation is simple to state, the problem is, in fact, more complex. As soon as a healthy body is made to shoulder the burden of certain ideals it also becomes subjected to a microphysics of domination and control. Technologies intrude into the body and mold perceptions of health, fitness, sexuality, and aesthetic beauty. These covert technologies present themselves in many instances as emancipatory strategies whereby the individual can free himself or herself from the mundane fact of mere biology. With specific reference to the athletic body, De Wachter points out that in trying to escape from the vagaries of nature—sickness and aging—we have subjected ourselves to a numbing array of techniques. Far from freeing the body we have simply subjected it to a different kind of determinism (1988: 123). Exercise and training produce an impression of “dynamism, differentiation, and freedom” but in fact fitness is simply another way of controlling the body. This is what Heinila (1982) has termed the “nightmare of totalization,” wherein fitness manifests itself as a mode of domination acting through progressively more detailed schemes of physical regimentation (in De Wachter 1988).

Exercise and health regimens dominate and control individual bodies in the same instance that they create an illusion of self-motivated physical liberation (Crawford 1985; Zola 1972). The illusion is two-dimensional: that we have somehow superseded the natural mandate of our biological bodies, and that the regimens we adopt are emancipatory and self-inflicted rather than ideologically prescribed. The mechanics of this premise rest on a tacit acceptance of the Cartesian mind/body duality. Because the body is regarded as a mere flesh and blood object, it is conceived of as a lifeless thing which can be molded. It can be disciplined, sacrificed, branded, tattooed, reproportioned, and developed through exercise. The mind (disembodied thought) is always regarded as the master of this game of control. In other words, we attribute cultural value to certain physical features, and we regard these values as taken-for-granted “natural facts” of life. Broad shoulders, for instance, are regarded as a natural feature of the male physique. While certain dimensions of physique are regarded as natural, others are regarded as inherently mutable—weight and body fat, for instance—and therefore subordinate to aesthetic, political, moral, and religious principles. Conversely, in the logic of Cartesian dualism, that which is physical is somehow regarded as more real and more elemental. Health, for example, is thought of as a purely physical condition, and illness as a purely biomedical referent. While the mind is accorded a position of supreme power in this scheme of human nature—the source of thought, logic, disposition, and emotion—it is the body which is regarded as basic to real life: a flesh and blood existence in the here and now.

Both mind and body—perhaps because they are radically dissociated from one another in Western thought—are subjected to external controls. The body is constrained by biological nature and the mind by history and the cultural construction of reality. Significantly, the mind also molds the body. But mind in this sense is not the individual mind of free will and individuality; it is the mind of ideology and collective consciousness. In the Cartesian formula, ideological thought is associated with the mind. The body is but an instrumental object of secondary significance, a purely dependent variable. By implication the body is always subject to control and can never serve as an autonomous agent through which ideas develop and change.

In Hindu philosophy the mind and the body are intrinsically linked to one another (cf. Staal 1983–1984; Zarrilli 1989). There is no sense of simple duality. In yoga, for instance, it is pointless to try to define where physical exercise ends and mental meditation begins. If one considers Gandhi’s adherence to yogic principles it is indeed difficult to draw any line between the physical, the mental, and the political.

The implications are significant. If exercise and regimens of fitness manifest themselves as ways of controlling the individual body, then in Hindu India one cannot have a disciplined body without also having a disciplined mind. In the context of Hindu schemes of discipline it is impossible completely to objectify the body. The end result of regimentation and disciplined exercise in India is therefore quite different from its Western counterpart. Rather than a “nightmare of totalization” where the body is subjected to a refined and detailed biomechanics of health and fitness, in India one has a situation where discipline endows the body/mind with a heightened sense of subjective experience and personal self-awareness. This is not to say that in India the individual experiences discipline as personal emancipation. In India, however, discipline is not simply manifest as an objectification of the body but equally as a subjectification of the self. This point may be elaborated and clarified through an example.

In American physical education and sport, strength is a purely physical phenomenon. It can be measured in objective terms: body mass, arm size, muscle-to-fat ratio, heart rate, weightlifting ability, and so forth. As such, strength is something that can be developed as purely somatic and as quantifiable and calibrated. While strength is also manifest as a physical attribute in India, it is, more significantly, linked to such ineffable cultural values as duty, devotion, and morality. It is neither purely somatic nor strictly quantifiable. A wrestler cannot be strong if he does not follow his guru’s mandate. He cannot be strong and indulge in sensual pleasure. Strength is manifest not only in the size of his arm but also in the sparkle of his eye and the luster of his skin, symbols that indicate spirituality, devotion, and moral control.

In a situation of mind/body synthesis such as this it is impossible to turn the body into a mere flesh and blood instrument molded to the image of some abstract ideological construct. Strength cannot be objectified from moral duty or spiritual devotion. The regimens of health and exercise practiced in India—yoga, vyayam, dietetics—exert control over the body not only through a physical mechanics of muscular training and organic chemistry but also through a disciplined regimentation of what we would call the subjective mind. As a result, discipline in India manifests itself not in the objectification of impersonal bodies, but in the complete demarcation of the person as a thinking, feeling, and acting microcosm of ideological values. In India a person’s individuality is constructed through the development of his or her body. In the West disembodied individuality is imposed onto a generic biological human form:

The physical training associated with wrestling is anything but depersonalized. Nor does the wrestler emerge, through exercise, as a generic man on a larger, stronger scale (except, as we shall see, in the synoptic arena of the tournament). The disciplinary regimens associated with wrestling produce a person charged with a heightened sense of self-awareness and moral duty. The wrestler’s physical strength is but one manifestation of a larger disciplinary matrix which entails moral, spiritual, social, and physical regimentation.The steel [of the machines and tools which bodybuilders use] depersonalizes. . . . Its homogeneity drives out the principles of individuality in the bodies that devote themselves to it. It does away with eccentricities—the dry and irritable skin, the concave faint-hearted chest, the indolent stomach. . . . On his/her contours, the bodybuilder watches emerging not the eccentricities his tastes and vices leave in his carnal substance, but the lines of force of the generic human animal (Lingis 1988: 134–135).

| • | • | • |

Exercise

Yoga

To understand the nature of physical exercise in the context of wrestling it is necessary to begin with the general concept of yoga. Broadly defined, yoga informs the underlying principles of the wrestler’s vyayam (physical exercise) regimen. Yoga is a vast topic of great complexity, and I make no pretense of discussing it in its entirety.

Technical designations aside, yoga has come to mean a particular type of physical training which serves to relax and develop the mind/body. In the classical literature yoga is classified in various ways. The most salient distinction is between Raja Yoga or meditation-oriented training, and Hatha Yoga, which focuses on kinesthetic movement. Even this distinction is, however, more schematic than real. After carefully delineating types of yoga, Atreya makes the following point:

In philosophy, yoga refers to the ontology of a particular system. In the Yoga Sutra yoga means the progressive control of the whole body. In the Tantras it refers to the symbiosis of the individual self with the universal soul. In Vedanta, yoga is the discipline through which one realizes oneself as part of the absolute Brahman.Here it is to be remembered that there is actually one Yoga, and not many yogas which are exclusively different from one another. The one purpose of all the yogas is to bring the body, the prana [vital breath], the unconscious and the sub-conscious strata of the mind, the mind and the forces of individuation, under one’s control; and to be conscious of one’s identity with the supreme reality which is within us as our very Self (1973d: 48).

The most complete dissertation on yoga is given in the Bhagavad Gita. While many definitions of the term are offered in this classic text, the most common and general is that yoga is the expert performance of one’s duties (Atreya 1973d: 45). Drawing primarily on the Bhagavad Gita, Atreya provides the following outline definition of yoga as a moral, ethical, and physical discipline.

Building up to a definition of yoga which includes wrestling, Atreya argues that one of the main objectives of yoga is to harmonize the whole body. By this he means the perfect functional interdependence of all of the body systems: digestive, respiratory, circulatory, nervous, and so forth. Overlying this functional harmony of the gross body is the control which must be exercised in order to channel physical energies to achieve disciplined goals.The word Yoga, therefore, now stands for the methods of a) realizing the potentialities of man; b) hastening the spiritual evolution of man; c) becoming one with the Divine Being who is immanent in all creatures; d) uniting the individual soul with God; e) realizing the highest ideal of man; f) becoming conscious of one’s unconscious powers and making use of them; and, g) attaining perfect health, peace, happiness, will, immortality, omniscience, power, freedom and mastery over everything in the world (ibid: 47).

The natural state of the mind/body is regarded in Hindu philosophy as basically flawed. Yoga is designed to compensate for the natural irregularities of the mind/body through the application of physical and mental control. Although one may practice yogic control and achieve a high degree of harmony, one is not completely healthy, Atreya argues, until one has achieved self-realization. Self-realization requires jivanmukti (release from the world; lit., having left life). In this condition ignorance is banished and replaced by spiritual consciousness and wisdom. Having achieved perfect health, a person is not plagued by emotions of any sort. One is simply no longer concerned with the sensory world of pain, pleasure, suffering, and greed.

Given such a broad definition of yoga, Atreya includes the art of wrestling within the general framework of yogic practices. Wrestlers do not necessarily perform the formal asans (postures) of Hatha Yoga, but they subscribe to the tenets of the more general yogic philosophy of a disciplined life. Narayan Singh, a teacher of yoga, wrestling, and physical education at Banaras Hindu University, agrees with Atreya’s point. In an interview he stated that yoga and vyayam are formally different but philosophically basically the same. Wrestling is a form of yoga because it requires that one transcend one’s natural physical aptitude and apply principles of sensory and nervous control to one’s own body. Wrestling is a subdiscipline of yoga since yoga is defined as a system of physical health, ethical fitness and spiritual achievement.

Pranayama (controlled breathing) is a primary aspect of yogic exercise and is also integral to wrestling. Atreya distinguishes eight types of pranayama (1965: 13). Only one of these, kumbhak, is employed in wrestling since it enables one to achieve great strength and stamina. The formal methods of pranayama that are refined in Hatha Yoga are not practiced by wrestlers to any great extent. However, wrestlers do recognize the general efficacy of breath control. It purifies the body and unfetters the mind. It helps cut through the maze of sensory images which obstruct the path to enlightenment. Breath control is a prerequisite for performing exercises of any kind. It is not enough just to breathe; that alone only satisfies the needs of the gross body. To breathe properly harmonizes the body with the mind: the spiritual with the physical.

A wrestler must breathe through his nose while expanding his diaphragm. A great deal of emphasis is placed on this point. If one gasps for air with an open mouth and heaving chest, it is likened to the agency of an inanimate bellows. Breathing in this fashion performs the function of putting air into the body and taking it out, but as such it is purely mechanical. Breathing through the nose—with conviction, concentration, and rhythm—transforms a mundane act into a ritual of health.

As a system of physical exercise, wrestling is integrated into the philosophy of yoga through the application of two principles: yam and niyam. As Atreya (1965: 11) explained in an interview, yam and niyam are the root principles of moral, intellectual, and emotional fitness. Yam has five aspects: ahimsa (nonviolence), satya (truthfulness), asatya (“non-stealing”), brahmacharya (continence/celibacy), and aparigraha (self-sufficiency and independence). Niyam also comprises five aspects: shauch (internal and external purification), santosh (contentment), tap (mortification and sensory control), swadhyaya (study), and ishvar-pranidhan (closeness to god through worship).

Development as a wrestler depends on the degree to which one is able to apply oneself to the realization of these principles. Wrestlers do not dwell on the philosophical complexities of yam and niyam. Nonviolence, for instance, is not considered problematic on an epistemological level. Neither do wrestlers seek to explain, or even understand, the metaphysical tenets of aparigraha, for example, or the distinction made between the external body (sthula sharir) and the subtle body (sukshama sharir). For them the intuitive application of these principles to their lives is the primary order of business. To be passive and even-tempered is in accordance with a lifestyle of ahimsa and santosh; to go to a Hanuman temple every Saturday is to be close to god. Exercise is a form of tap, and going to the akhara every morning is an act of internal and external purification. All of this is not to say that wrestlers are yogis in any strict sense of the term. They are not concerned with the metaphysics of their way of life or with spirituality as an esoteric endeavor. For them the goal is practical in both a physical and a social sense. Yam and niyam develop the wrestler’s body/mind and also define for him the basic moral principles of life as health.

Vyayam

Vyayam is a system of physical training designed to build strength and develop muscle bulk and flexibility. It is in sympathy with the concept of health and fitness articulated through yoga. Yam and niyam are central to its practice. Unlike yoga, however, vyayam emphasizes physical strength. Where Hatha Yoga concentrates on the harmonization of all aspects of the body, vyayam builds on this harmonization through calisthenic and cardiovascular exercise. As with yoga, a key concept in vyayam is the holistic, regulated control of the body. In yoga, however, the body is manipulated through the practice of relatively static postures. Vyayam disciplines the body through strenuous, patterned, repetitive movement.

K. P. Singh has delineated twelve rules of vyayam (1973). Although his list is not exhaustive, it is useful in terms of understanding how vyayam is conceptualized as a system of physical fitness: 1) One should arise before dawn, defecate, bathe, oil oneself and go to the akhara. 2) At the akhara tie on a langot and join the company of other like-minded wrestlers who have focused themselves on the task at hand. Be sure that the place for exercise is clearly demarcated, for it is no less important to define a place for exercise and physical training than for spiritual contemplation. 3) Do not start off by over-exercising. Pace yourself so that you will not be exhausted. 4) Regulate your exercise regimen by either counting the number of repetitions, or timing the duration of your workout. Only in this way will your body develop at a regular and consistent pace. 5) Do not fall into the practice of exercising at irregular intervals. Exercise every day at the same time. 6) One should breathe deeply and steadily while exercising. Each exercise should be done to the rhythm of a single breath. Needless to say, one should breathe only through the nose. 7) Beware of sweat. Oil your body before exercising. The oil will fill the pores and prevent rapid cooling. 8) Focus your mind on each exercise. If your mind wanders you will not develop strength. Consider the laborer who works all day long. He is not as strong as the wrestler for he does not concentrate on his labor but thinks about other things. 9) Do not sit down after exercising. Walk around to keep warm and loose. If you exercise inside, walk around inside. If you exercise outside, walk around outside. 10) Get enough rest. Take one day off every week. Be asleep by eight in the evening. 11) Do not exercise on either a full or empty stomach. Also do not exercise if you have not evacuated your bowels. Do not smoke or chew tobacco. 12) Drink a glass of juice before exercising, and drink milk or some other tonic after exercising. This will help to focus your mind and relax your body.

As a system of fitness, vyayam comprises specific exercise routines.

Surya Namaskar

Surya namaskar (lit., salutation to the sun) is a hybrid exercise which integrates aspects of vyayam training with yogic asans. While based on formal yogic principles, surya namaskar also serves to develop physical strength. Although surya namaskars have undoubtedly been practiced for centuries (cf. Mujumdar 1950), the exercise was routinized and made popular by the late raja of Aundh, Bhawanrao Pantpritinidhi. Raja Bhawanrao believed that if everyone performed this exercise religiously, the result would be a stronger and more upright nation (Mujumdar 1950: xxiv). In a book entitled Surya Namaskars, Bhawanrao’s son, Apa Pant, makes the following observation:

It is precisely this kind of experience which Bhawanrao was attempting to transpose onto a national level to the end of ethical and moral reform. In the beautiful and harmonized movements of surya namaskar, Bhawanrao clearly saw the harmonized body of a united Indian polity that would turn, collectively, away from the gross sensations of modern life—sex, drugs, power, pride, prosperity (ibid: 12–14)—and toward the pure experience of self-realization.[Surya namaskar] is not a religious practice in the narrow sense of the term. But it does have a deep spiritual content and it opens up a new, more profound, more powerful dimension of awareness. Slowly but surely as one continues regularly to practice it, things change in you and around you. Experiences miraculously come to you and you feel the full force of the Beauty and Harmony, the unity, the oneness, with all that is (A. B. Pant 1970: 2).

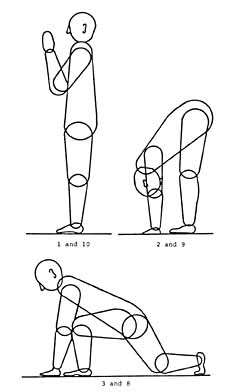

Surya namaskar consists of ten body postures which together constitute a rhythmic flow of motion (see figures 1a, b). Each posture is punctuated by the recitation of a short mantra to the rhythmic cadence of pranayama.

To perform surya namaskar one should clear a space at least two and a half meters long by one meter wide. This space should be oriented towards the rising sun. One should wear as little as possible so that movement will not be inhibited.

Position One: With feet together and back and legs straight but not rigid, bend your arms at the elbow and fold your hands in front of your chest. Breathe in deeply through your nose with full concentration. Focus your mind on your posture and your breath.

Position Two: From position one, bend and place your palms flat on the ground on either side of your legs. Your palms should be a forearm’s length apart. Keep your legs straight and touch your nose to your knees. Keeping your arms straight, tuck your chin into your chest. Breathe out slowly and evenly as you reach this position. Always breathe with your stomach: in, stomach out; out, stomach in.

Position Three: From position two extend one leg back as far as it will go and touch the knee to the ground. Arch backwards at the same time and lift your head back as far as it will go. Breathe in while doing this and push your stomach out. Always be alert and concentrate on each movement, breath, and sensation. At the same time remain detached and relaxed.

Position Four: Move your second leg back so that both legs are extended backwards. Lift both knees off the ground so that your weight is supported on your palms and toes while your body is held straight. Touching your chin to your chest, look down at the ground between your palms. Hold your breath in this position.

Position Five: This is the most important and central position of the exercise. Bend at the elbows so that your body descends to the ground. Insure that your body touches the ground at only eight points: the two sets of toes, the two knees, chest, forehead, and the two palms. This part of the surya namaskar is called the ashtanga namaskar, or eight-pointed salutation. All eight points must touch the ground at the same time. As they come in contact with the ground you should exhale.

Position Six: In order to move from the fifth to the sixth position lift your head up and bend your neck backwards. Then, without exerting pressure on your arms, lift the trunk of your body off the ground by contracting your lower back and gradually extending your arms. Your spine should be fully arched from the top of your neck to the base of your tailbone. Breathe in while assuming this position and again concentrate on each part of your body.

Position Seven: In position seven you reverse the arch of your body by lifting your buttocks into the air as far as possible while extending your arms and legs. Your hands and feet should not move. Breathe out in this position.

Position Eight: This position is a repetition of position three. It is achieved by moving one foot forward and placing it between your palms. Arch your back and bend your head backwards. Breath in deeply.

Position Nine: Bring your other leg forward and place both feet together. Straighten your legs and tuck your chin into your chest. Breathe out with force. This is a repetition of position two.

Position Ten: This position brings you back to the starting point of the exercise. Breath in as you stand erect and fold your hands in front of your chest.

While doing surya namaskars one is enjoined to recite six bij mantras (seed sounds). Not only does one pay obeisance to the sun by reciting these mantras, they also reverberate through the body in an efficacious manner. Pant points out that these reverberations invigorate the mind (1970: 9). There are six primary bij mantras: Om-Haram; Om-Harim; Om-Harum; Om-Haraim; Om-Harom; Om-Hara. In accompaniment to the six bij mantras one should recite the twelve names of the sun: Mitra (friend); Ravi (shining); Surya (beautiful light); Bhanu (brilliant); Khaga (sky mover); Pushan (giver of strength); Hiranya Garbha (golden centered); Marichi (Lord of the Dawn); Aditya (son of Aditi); Savitra (beneficient); Arka (energy); and Bhaskara (leading to enlightenment).

Surya namaskars integrate and harmonize all aspects of the physical, intellectual, and spiritual body. Position two energizes the pituitary, pineal, and thyroid glands. Position three stimulates the liver, solar plexus, and pancreas. Position four stretches the spinal column and facilitates blood flow to all of the organs and glands in the immediate vicinity of the spine. Positions five and six are particularly efficacious for the neck, chest, abdomen, and sexual glands. The regular performance of surya namaskars is intended to raise one’s state of consciousness to a higher level of self-realization. As Pant notes, one can then transpose this experience of self-realization—which he refers to as bliss, harmony, knowledge, beauty, and awareness of the infinite—onto one’s experience of everyday life.

Surya namaskars are more popular among older men than among young wrestlers. While they strengthen the body, they do not strain the muscles, bones, and organs of the body. Surya namaskars are not vigorous, and senior wrestlers practice them in order to maintain their physique and stature. In any case, surya namaskars are clearly associated with physical strength and muscular prowess. Shivaji’s guru, Samarath Ramdas, was said to perform 1,200 surya namaskars every day. Shivaji himself and Ramdas’s other disciples also performed surya namaskars. Mujumdar attributes Maratha physical prowess and military success to this exercise (1950: 54).

With regard to wrestling discipline, surya namaskar is important insofar as it represents the formal synthesis of yoga and vyayam. This synthesis is implicit in many of the exercises which wrestlers do. As we shall see, the combination of dands and bethaks echoes the basic movement of surya namaskar.

Dand-Bethak

Dands and bethaks are two different exercises, but together they constitute the core wrestling vyayam regimen. Dands are jackknifing push-ups and bethaks are comparable to Western-style deep knee bends. Although dands and bethaks are done separately, they are usually referred to as a pair. As a set they provide a complete body workout.

One starts a bethak from a standing position with feet set at forty-five degree angles and heels about fifteen to twenty centimeters apart. While squatting down one should jump slightly forward onto the balls of one’s feet while lifting the heels clear off the floor. In the process of standing back up, one should jump backwards to the position from which one started. One’s arms should be relaxed. They should sway with the movement of the body in order to maintain balance. One’s eyes should be fixed on a point about four meters forward on the ground, so that one’s head will be stationary and balanced. One should do about sixty or eighty bethaks per minute and between sixty and one hundred at a stretch (Atreya 1974: 25). All of this depends, of course, on the degree of one’s strength and previous experience. Similarly, the number of bethaks one does is relative to personal strength, predilection, available time, and specific goals. Well-known champions do between two and three thousand bethaks a day. Average wrestlers often do as many as one thousand. At the very least a wrestler will do between five and eight hundred per day.

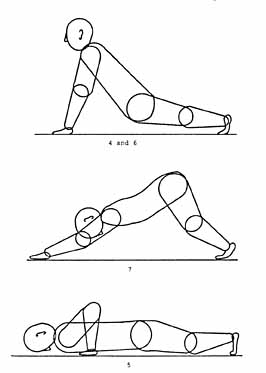

Dands are similar to certain aspects of surya namaskar. One starts a dand from a face-down, prone position with feet placed close together and palms flat on the ground directly below the shoulders about half a meter apart. To begin, one cocks the body back by lifting one’s buttocks into the air while straightening both arms and legs (see figure 2). Bending at the elbows, one dives forward so that the chest glides between the palms close to the ground. One then arches up while straightening the arms and thrusting the pelvis down towards the ground. One then recocks the body to the starting position.

According to Atreya one should do half as many dands as bethaks (1974: 21). Once one has assumed the position of doing dands one should not move until all dands are completed. A good wrestler in the prime of life can do about 1,500 dands per hour, and many do as many as 2,000 a day. Those wrestlers who swing joris and gadas as the main aspect of their routine do as many as 5,000 dands per day, but this is exceptional. Whereas bethaks are more often than not performed before jor (see below), dands are performed at the end of the morning practice session. However, there is no strict rule regarding the sequence of an exercise regimen. Many wrestlers do their dands and bethaks in the evening.

The most important feature of dands and bethaks is that they be done rhythmically and at a steady pace. The performance of thousands of these exercises produces a mental state not unlike that of a person who has gone into a trance through the rote recitation of a mantra or prayer. Thus, dands and bethaks transport the wrestler into an altered state of consciousness from which he derives psychic and spiritual purification. Vyayam is very much like meditation in this respect. I was told that Jharkhande Rai, a champion wrestler who used to be a member of Akhara Ram Singh, would concentrate so hard on doing his dands that his sweat would leave a perfect image of his body as it dripped onto the earth. This and similar stories were told in order to make the point that the wrestler involved was often not even aware of the extent of his exertion. Many times I have sat on the edge of an akhara and watched a wrestler bob up and down for half an hour or more without taking his eyes off an imaginary point on the ground in front of his face. It is not surprising that the beneficial effects of dands transcend the mere physical body and strengthen aspects of moral and ethical character. Atreya points out that dands strengthen the wrists, fingers, palms, neck, chest, and back. Dands also cure all kinds of illnesses relating to semen loss (impotence, infertility, and spermatorrhoea) and faulty digestion (1974: 19). Dands strengthen the sinews of the body, and they also develop character:

As one of the central exercises in a wrestler’s vyayam regimen, it is clear that dands do more than develop the gross body. They develop the personality of the wrestler as well. The wrestler’s personality derives its strength—as a charismatic social force and as personal self-confidence—through the symbiosis of a personal experience akin to enlightenment and a physical experience of muscular development. With regard to both dands and bethaks Atreya makes the following observation:Doing dands makes a person’s character and personality shine. The body takes on a powerful radiance. Not only this, but the person who does dands lives a fuller and more meaningful life. His personality is more attractive. He is liked by everyone. His whole attitude towards life is changed (ibid: 20).

Dands and bethaks make the muscles of the body so incredibly strong that the wrestler appears divine. Dands and bethaks are the mirror in which the aura of wrestling is reflected. They are the two flowers which are offered to the “wrestling goddess.” Dands and bethaks are the two sacrifices made to the goddess of wrestling. If she is pleased she will bestow great strength and turn mere men into wrestlers (ibid).

Jor

As distinct from the term kushti, which is used to denote competitive wrestling, jor is the term used for wrestling done for practice, training and exercise (see plates 7 and 8). In the same way that surya namaskar is not only a form of devotion but also an exercise, so is wrestling not only a sport but also a form of mental and physical training. Implicitly if not explicitly, therefore, jor integrates some of the basic principles of yoga into the act of wrestling.

When wrestlers come to the akhara in the morning, each spends between one and two hours practicing jor. After the pit is dug, smoothed, and blessed, two senior wrestlers take to the pit and begin to wrestle. Given the nature of wrestling as a competitive sport, each wrestler tries to throw his opponent down to the ground through the correct application of particular moves. Each move is countered by a defensive move and this sparring continues indefinitely. The nature of jor is, however, significantly different from a competitive kushti bout.

In kushti tournaments (dangals) the aesthetic of structured motion is achieved through a radical opposition of movements. The tone of this aesthetic is harsh, for every move is matched with a countermove. In jor, however, both wrestlers tend to work together so that the moves which are applied are executed smoothly. The dangal produces a dramatic grammar of movement with sudden moments of brilliance and, ultimately, clear superiority manifest in the success or failure of one or the other wrestler. Jor, on the other hand, tends to emphasize the harmony of the art of wrestling as it is manifest in the details of each move. The emphasis in jor is to apply a move with precision and a minimum of effort. Jor is very much like some forms of dance.

In jor you must focus your mind at once on the details of each move and on the whole of which those moves are a part. As in surya namaskar you must focus your mind on the exact posture of your body as it moves from stance to stance and from move to countermove. As pointed out earlier, it is imperative to keep one’s guru’s name in mind while practicing jor or any other form of vyayam. The guru’s name functions as a spiritual beacon which channels the energy of enlightenment into the body of the wrestler. At Akhara Ram Singh the dadas and other senior wrestlers had a clear idea of who was concentrating on their practice and who was not. If a wrestler opened his mouth to gasp for air it was evident that his concentration had been broken. Any wrestler who appeared to be uninterested or not putting out a full effort was quickly rebuked by others.

As choreographed, regulated movement, jor has clear physical and mental benefits. It exercises every part of the body. Anyone who has wrestled for even a few minutes will soon realize that wrestling brings into play muscles which are not usually called upon to exert force or support weight. Unlike exercises like running, jumping, or lifting weights, jor does not require one to perform repetitive movements. In the course of a jor session, certain sequences of moves will, of course, be repeated. In the abstract, however, the exercise is conceived of as an unbroken chain of movement. In this regard jor is the antithesis of vyayam exercises like surya namaskar, dands and bethaks. While these exercises are mechanically repetitive, jor is almost wholly improvised.

Jor develops stamina as well as strength. As such, wrestlers place a great deal of emphasis on breath control. One should never pant or gasp. Never breathe simply to satisfy the body’s need for oxygen. One must breathe in and out regularly and with deliberate, conscious thought. This serves to focus the mind on the application of specific moves. Many wrestlers with whom I spoke said that practicing jor in the morning cleared their thoughts and invigorated their bodies, allowing them to go about their lives with more vitality. What wrestlers mean by clearing their thoughts and invigorating their bodies is the same experience articulated by those who practice yoga. Through the practice of jor one is able to achieve a higher state of consciousness which is one step closer to self-realization. This self-realization can be directed towards winning in competitive bouts or, more generally, towards living a richer and more fulfilling life. As Harphool Singh writes,

Singh continues his dissertation on the efficacy of jor specifically and wrestling in general by saying that wrestlers must always be happy, and present themselves to the world as people who take great pleasure in life. The experience of jor plays no small part in enabling the wrestler to affect such an attitude.Wrestling in the earth makes the body elegant. Exercising in the earth removes pimples, unwanted hair and cures eczema while making the skin shine like gold. Exerting oneself in the earth and becoming saturated with sweat and mud makes the wrestler feel invigorated. Minor ailments aside, it is said that akhara earth can cure cholera and other serious diseases. One thing is for sure, however: after bathing, the wrestler who has exercised in the akhara earth will feel a sense of vigorous satisfaction as his mind becomes clearly focused. (1984b: 22)

Atreya has drawn up seven points to help define where, when, how, and with whom one should practice jor (1985: 23). Although these guidelines are not followed as rules, they do define the basic principles of jor.

- You should begin your jor regimen by wrestling with a young child or a wrestler who is clearly weaker than you. In this way you can warm up while the younger wrestler gets a chance to exert his full strength. You should always be careful to match strength with strength and never beat a younger wrestler simply to prove your superiority. As a senior wrestler you must draw the younger wrestler out to his full potential.

- After wrestling with a younger and weaker wrestler you should wrestle with someone who is your equal. This will enable you to exert your full potential. You should not try to win. Neither should you lose sight of the fine points of the art to the end of showing off your skill. You should match move for move and countermove with countermove in a balanced exchange of strength and skill.

- If you are called upon to practice jor with a foolish or braggart wrestler you should show him no mercy. He must be cut down to size immediately. Only in this way will he recognize that strength does not lay in conceit, but rather in the regulated practice of moves and countermoves. This must be done. Conceit clouds the mind and a wrestler will never be able to succeed or benefit from the practice of wrestling if he is ignorant of its basic tenets.

- When wrestling with a stronger and more senior wrestler you should exert all of your strength but at the same time show deference to his rank. This is a very difficult thing to do. It is imperative, however, if you hope to advance and improve. You should learn from a senior wrestler but apply what you learn on someone who is your equal. Thus your achievement will never challenge the seniority of the other wrestlers in the akhara.

- When wrestling with an old wrestler one must show respect and deference. Never wrestle as though you are stronger than him even if he is old and weak. Always seek to make the older wrestler feel good and strong.

- If you practice jor with a well-known wrestler you should assume the posture of a disciple at the feet of his guru. You should show respect for well-known wrestlers, and it is also important to learn from them. You should not assume that your strength or skill is a match for theirs.

- When wrestling with the best wrestler of an akhara you should always approach him in a forthright and confident manner. But never pin him down even if you are able. If you try to prove your strength then the practice of jor turns into a contest. As a result no one comes out of the session having gained any knowledge.

Atreya also delineates six places where one may practice jor: at your own akhara, at a competitor’s akhara, at some akhara in another district, at the akhara of a village or town where one has gone to compete in a tournament, at a bus or railway station, and while on a journey. In each of these contexts there are rules for proper comportment. You should not, for instance, show your true form while wrestling in someone else’s akhara. At the same time you must show respect for your host wrestlers. When at a dangal you should only practice with compatriots from your own akhara. Atreya’s list of places where one may practice jor is fairly inclusive, but there are places where it is deemed inappropriate to engage in jor. One should not practice at home, for instance.

In jor a great deal of importance is placed on who one practices with. Similarly, comportment is integral to the performance of jor. Only by adhering to the above-outlined principles is one able to learn the actual techniques of wrestling. This is to say that jor properly done is as much a matter of social decorum and personal attitude towards seniority as it is a question of purely physical training. Atreya tells of a young wrestler who thought that he was stronger and more skilled than an old but well-known wrestler. He practiced jor with the senior wrestler as though they were equals. As a result he began losing wrestling bouts and became weak and unhealthy.

Joris and Gadas

Joris and gadas are heavy clubs which wrestlers swing in order to strengthen their shoulders and arms. At Ragunath Maharaj Akhara, Akhara Morchal Bir and other gymnasia, jori swinging is both a competitive sport and a form of exercise.

Joris are always swung in pairs (see plate 3). Those used for exercise usually weigh between fifteen and twenty-five kilograms each. They are carved of heavy wood and are weighted with bands of metal. In order to make the joris more difficult to swing, blades and nails are sometimes hammered into them.

At the beginning of the exercise, the joris are held in an inverted position. Each jori is swung alternately behind the back in a long arch. At the end of the arch each jori is lifted or flipped back onto the shoulder as the opposite jori begins its pendulum swing. Timing is an important part of this exercise. The balanced weight of one jori must facilitate the movement of the other. Jori swinging exercises the arms, shoulders, chest, thighs, and lower back. Wrestlers tend to swing fairly lightweight joris because they say that the heavier clubs cause the upper body to become rigid.

In contrast to the intricately carved silver and gold symbolic gadas (macelike clubs) depicted in art and used as wrestling trophies, gadas used for everyday exercise are rather plain. An exercise gada is a heavy, round stone, weighing anywhere from ten to sixty kilograms, affixed to the end of a meter-long bamboo staff (see plate 4). The gada is swung in the same way as a jori except that only one gada is swung at a time. A gada may be swung with either hand or both hands at once.

The swing begins with the gada balanced on one shoulder. It is then lifted and shrugged off of the shoulder and swung in a long pendulum arch behind the back until it is flipped and lifted back onto the opposite shoulder. The gada is held erect for a split second before it is swung back in the opposite direction and onto the other shoulder.

Gada and jori exercises are counted in terms of the number of hath (hands) that one is able to do. One gada “hand” is counted as the movement from one shoulder to the other. One jori “hand” is counted as the combined swing of both right and left clubs. Unlike dands and bethaks, which number in the thousands, wrestlers tend to swing gadas and joris for sets of relatively few repetitions. Those who swing joris and gadas on a regular basis place a higher premium on the amount of weight lifted than on sheer number of hands swung.

Dhakuli

After jor wrestlers practice dhakulis (somersaults/flips). There are several variations on this exercise and all types emphasize twisting rotations. When performed in competitive bouts these twisting rotations enable a wrestler to escape from his opponent’s grip.

To perform the most common dhakuli you start from a kneeling position in the pit. You lean forward and place your head on the earth. Then shift your weight from your knees to your head and neck. Standing briefly on your head, with legs bent, you twist so that you land on your knees facing in the opposite direction. This exercise requires a great deal of neck strength, and many wrestlers use their hands for balance and weight distribution.

Another dhakuli resembles a one-handed cartwheel. Standing in the pit you place your left hand on the earth. Flip your body over so that you land on your right shoulder and side. This procedure is reversed so that you get practice falling in a disciplined manner. A variation of this dhakuli is to jump and fall alternately onto each shoulder without using either hand for support.

In order to strengthen their necks, wrestlers practice “bridges” of various sorts. The most common bridge performed by Indian wrestlers is identical to the common Western form. You lie on your back in the pit, and lift your body up into a reverse arch using only your neck for leverage and feet for support. A variation of this is to lie on your back and arch off the ground enough so as to be able to roll over. As you rotate on the top of your head, your arched body rolls over and over. You cross your legs over so that you move in a circle around the axis of your head and neck.

Shirshasan

Shirshasan (head stand), like surya namaskar, is an adapted form of a common Hatha Yoga technique. Wrestlers often stand on their heads—as in the dhakuli routine—both to strengthen their necks and to increase the flow of blood to their heads. This is said to clear the mind of impure thoughts and to bestow a general sense of health and well-being. It is generally recommended for all young men who suffer from spermatorrhoea or who show symptoms of emotional distress.

Nals

Nals are roughly equivalent to Western free weights and are lifted to develop arm, shoulder, and back strength. Nals are large, cylindrically carved stones which are hollowed out. A shaft of stone is left in the center of the nal’s hollow core and is used as a handle. Nals usually weigh about thirty kilograms, but come in all sizes and weights. There does not appear to be any set way in which nals are lifted. The general idea is to lift the weight with one or both hands from the ground to above your head in one smooth motion. As with joris and gadas, those who lift nals place more emphasis on the weight of the stone than the number of times it is lifted. For the most part nals have been replaced by Western-style free weights.

Gar Nals

Gar nals (circular stone rings) are used to weigh down a wrestler as he does dands or bethaks. As the term gar (neck) would indicate, gar nals are hung around a wrestler’s neck in the fashion of a giant necklace. Many akharas still have one or two gar nals on the premises, but very few wrestlers use them. It is said that Gama used to do dands while wearing such a large gar nal that a trench had to be dug between his hands so that the stone would not drag along the ground.

Other Exercises

Wrestlers do a host of other exercises, and each akhara has its own particular regimen of training techniques. Virtually all akharas advocate rope climbing and running. Many akharas are equipped with large logs or heavy pieces of lumber to which wrestlers harness themselves. Pulling these around the pit strengthens the lower back, thighs, and feet while it also develops stamina (see plate 15). Wrestlers are often instructed to run at least a few kilometers before coming to the akhara in the morning in order to build up both speed and endurance.

Some gurus advocate various games which serve to build stamina and speed. One popular game is referred to as langur daur (monkey’s run) wherein wrestlers run around the perimeter of the pit on all fours trying to catch whoever is in the lead. To strengthen their legs and feet, wrestlers often run around the akhara weighted down with someone on their backs. To build up their arms and develop coordination and balance, they have someone hold up their legs as they run around the pit on their hands. Sometimes a wrestler will lie face down in the pit and have a heavier wrestler sit on him as he tries to stand up. Jumping rope has not been adopted by many Indian wrestlers, but jumping up and down in place or hopping around the akhara on one foot is common. Some wrestlers develop idiosyncratic exercises. I have heard of some who push cars to develop their legs. Others fill up gunnysacks with sand and lift, kick, and throw these as they see fit. In rural areas some wrestlers harness themselves to plows, grinding stones, and waterwheels. I was told of one wrestler who started his exercise regimen by carrying a buffalo calf across a river. He did this every day until after a year he was able to lift and carry a full-grown buffalo with ease.

Although formal exercises are clearly distinguished from everyday physical activities, there is a sense in which work, as physical labor, is translated by the wrestler into a form of exercise. Railway porters in particular regard carrying heavy loads as a way in which they develop their strength. Undoubtedly there are many porters who regard such hard and poorly remunerated work as simply tiring. However, the wrestling porters I know have successfully interpreted what is in fact a form of exploitation into a form of productive exertion. They have embodied their own labor power, so to speak. Similarly, many of the young wrestling dairy farmers I know speak of milking cows and buffalos as a form of exercise rather than work.

Ban

Wrestlers practice a number of “pair exercises” of which the most popular is ban. Ban (literally arrow) is performed as an exercise which both develops strength and which also serves as a muscle massage. The exercise resembles the movement required to draw a bow.

Two wrestlers stand facing each other about one and a half meters apart. They lean into each other and with their right hands grab hold of each other’s left upper arm (see plate 5). Both wrestlers push back with their left arm and try to dislodge their partner’s hand. The position is then reversed as both wrestlers push with their left hand against their partner’s right arm. The idea is to resist your partner’s push with as much force as possible and to dislodge his gripping hand as quickly as you can.

Ban expands the chest muscles and develops coordination. It also serves the valuable function of toughening upper arm skin. When practicing jor the upper arm is one of the areas of the body most often used as a fulcrum. As a result it is often bruised, stretched, and rubbed raw unless toughened up beforehand.

In addition to being a popular exercise for the reasons mentioned above, many wrestlers claim that ban serves to shape their upper body in an aesthetically pleasing way. It gives them the barrel-chested, turned-out arm stance characteristic of a well-built wrestler. Jori swinging and dands are also said to have this effect.

There are also various other pair exercises which some gurus place more emphasis on than others. To strengthen neck muscles and generally to toughen the head and ears, wrestlers alternately slap one another on the side of the head with their forearms. Variations on this general theme are to strike forearm with forearm, shoulder with shoulder, and chest with chest. A fairly common exercise for the neck is for two wrestlers to pull against the back of each other’s head until one or the other gives up or is forced to fall forward. A popular exercise at Akhara Ram Singh is for a wrestler to get down in the pit on his hands and knees with his forehead pressed to the earth. His partner then kneels on his neck with one knee. On all fours, the wrestler tries to lift the weight of his partner, thus exercising his neck and upper back. This exercise is called sawari (the passenger). Variations on sawari are numerous: while doing dandas, one wrestler will have another stand on his legs; while doing bethaks one wrestler will ride on the other’s back.

Group exercise, although not common, is also practiced in some akharas. One form of this exercise is for a wrestler (usually the biggest) to lie down or kneel in the center of the pit, and then a group of five or ten younger wrestlers do their best to keep him from getting up. Often such exercises are done toward the end of the jor period and will climax in a free-for-all where the senior wrestler turns the tables and sees how many junior wrestlers he can hold down at one time. Exercises such as these are as much games as they are regimented forms of physical training, but as more than one wrestler has put it, group exercises create a sense of community health among the wrestlers involved. Such group exercises are often referred to as masti, which, for lack of an adequate gloss, may be translated as an invigorated sense of feeling on top of the world.

The vyayam exercises mentioned above are not simply ways in which the physical body is developed as a mechanical, biological entity. One must bear in mind that vyayam is performed in an environment saturated with ideological significance. This fact becomes more explicit when massage is considered.

Massage

Among wrestlers, massage is regarded as a very important exercise (see plate 6). In the akhara regimen, Wednesday of every week is set aside for massage. Being a good masseur requires a great deal of skill, and there are some wrestlers who are well known for their ability to manipulate tendons, joints, and muscles so as to relieve pain and stress. Most wrestlers, however, are not highly skilled in this regard. They are, however, familiar with some basic principles and techniques.

The first principle, as outlined by Shyam Sundaracharya, is that each muscle group or appendage must be massaged along its whole length. The masseur must stroke his hands along the wrestler’s arm, back or leg. The second principle is that of pressure massage. Pressure is applied in various ways on various parts of the body, but most wrestlers simply apply pressure with the heels of their hands. This loosens the muscles and makes them flexible. The third principle is that of friction massage, wherein the skin is rubbed vigorously so that a tingling sensation permeates the body. Finally, in order to strengthen the circulatory system, there is the fourth principle of vibration. Vibration is applied through the rapid movement of the hand and wrist at the same time that pressure is brought to bear on a particular part of the body (1986b: 37).

A typical massage routine at Akhara Ram Singh is as follows. The wrestler being massaged sits on a low step with the masseur standing in front of him. Mustard oil is liberally applied to the wrestler’s legs. The masseur rubs each thigh alternately from the knee up to the hip joint. He then takes the wrestler’s arms and places each in turn on his shoulder. Working from the shoulders to the wrist he pulls down and away from the wrestler’s body, thus rubbing, in turn, the wrestler’s bicep, elbow, and forearm. The wrestler’s calves are massaged in the following manner. The masseur sits on the ground with the wrestler’s foot wedged between his own two feet. The wrestler’s leg is bent and the masseur pulls and rubs his hands across the wrestler’s calf from side to side and top to bottom.

A back massage is performed in various ways. The most common is for the wrestler to lie face down on a special wooden bench while the masseur leans over him. Using his forearm and applying his body weight, the masseur slides his arm down the wrestler’s back. While the wrestler who is being massaged is face down on this bench the masseur may decide to use his feet in order to apply a great deal of focused pressure on particular parts of the body. I have seen a skilled masseur walk the full length of a wrestler’s body, from ankles up to neck and out to either hand. Full body weight is not applied to all parts of the body and so a masseur must carefully gauge his own body-weight distribution relative to the type of massage required.

Every guru has his own ideas of what massage technique is best. As Atreya has pointed out (1986b: 29–30) it is fruitless to try to define rules for something which is inherently idiosyncratic. Irrespective of the fact that massage is performed in various ways, however, the virtues of massage, as an aspect of physical training, are generally agreed on.

Most significantly, massage makes the body both flexible and taut. In wrestling one must develop muscles which are supple and strong. Stiff muscles inhibit movement and prevent the application of certain moves. There is also the danger that an arm or leg may break if it is unable to bend freely. In this regard massage helps develop the wrestler’s muscles in a manner suited for the practice of wrestling. On a more general level, however, massage has a calming effect on the whole body. If one is suffering from physical fatigue or mental exhaustion, Sundaracharya notes, massage reinvigorates through structured relaxation (1986b: 35). In massage, as in many other vyayam exercises, there is a clear synthesis of mental health with physical fitness. One important aspect of massage is that it functions to fine-tune the body. In other words, through massage a wrestler achieves a condition where his state of mind is a direct reflection of his state of body. In this way massage serves to reiterate the tacit link between body and mind which is integral to vyayam as a whole. Through massage one is reminded, for instance, that relaxation is as much a question of attaining release from worldly concerns as it is a function of the circulation of blood through the base of one’s spine, knee joints, and shoulder tendons.

Technical massage requires a detailed understanding of human physiology. Although I am not qualified to speak to this aspect of massage (nor are there any wrestlers I met who possessed such technical knowledge), my suspicion is that North Indian massage is based on a concept of the body that does not isolate body parts, organs, tissues, or skeletal structure in the same way as in comparable Western techniques of chiropractic massage. More specific and comparative data are required, but the science of Indian massage seems to be based on a logic of heat and substance flow, with substance being some combination of neuroendocrinal fluid and blood. Fluid movement along the body’s various channels seems to depend on a complex equation of heat, density, and tissue depth, as well as other factors. In this regard Zarrilli (1989) has outlined the complex massage and health techniques which are part of the South Indian martial art called kalarippayattu. The practitioners of kalarippayattu have a fairly unique understanding of the human body and are able to effect cures for a range of ailments through the application of complex, secret methods of pressure massage. The massage technique associated with marma prayogam is far more sophisticated but probably not completely different from that which North Indian wrestlers practice. Both systems stem from a similar understanding of body physiology.

As a vyayam technique, massage reflects the complete symbiosis of mind and body which is also found in yoga asans, surya namaskar, dand-bethak, and jor. As an institutionalized practice in akhara life, however, massage also has very significant social implications with regard to hierarchy and purity and pollution. We have seen that jor requires a symbiosis of social rank and status concerns with practical techniques of body movement. In the same way, massage requires a reconciliation of social status with physical interaction. One cannot completely benefit from a massage without taking into account—and reconciling oneself to—what massage means in terms of personal interaction. This issue turns on the important question of who massages whom in the akhara. Atreya writes:

Atreya goes on to decry the present state of affairs where wrestlers regard it as beneath their dignity to be masseurs. Atreya’s criticism is, in my experience, somewhat exaggerated. In many Banaras akharas there is a clear hierarchy of who massages whom, and this hierarchy follows the rank of seniority and age. However, rank hierarchy is not rigidly defined. Flexibility is built into the system. Two wrestlers who are roughly equal in age and skill will both be massaged by much younger wrestlers who are clearly their juniors. In turn these wrestlers will massage much more senior wrestlers who are clearly of a higher rank. Any ambiguity in rank status is displaced to a plane where status is no longer ambiguous. What is significant, however, is not so much the rank order of wrestlers, but the general principle of rank hierarchy as such. Many of the senior wrestlers with whom I spoke were very clear on this point. Massaging one’s elders serves to reinforce an ethic of humility, respect, service, and devotion. Massaging one’s guru’s feet, is, after all, the ultimate sign of devotion.Indian wrestling has never been practiced without the aid of massage. It used to be that in akharas the practice of massage was structured in a very beautiful way. As a result wrestling flourished, and India was regarded as a nation of champions. [Younger] wrestlers would massage senior wrestlers, sadhus, and the oldest men in the akhara. It was a matter of showing deference and respect. From this wrestlers received two benefits. On the one hand giving a massage was a form of exercise. On the other hand, by massaging one’s guru and other senior members of the akhara one received their blessing (1986b: 28).

Embedded within this system of rank hierarchy based on age and skill is a seemingly contradictory principle of inherent equality. Although the principle of rank applies to those who are clearly junior or senior, the majority of akhara members are roughly the same age. On this level wrestlers take turns massaging one another, thus reinforcing their equality. Atreya points out that this serves to underscore feelings of mutual respect.

It is important to note that massage, like wrestling itself, entails close physical contact. A masseur must not only touch another person, he must also touch that person’s head and feet, which are, respectively, the purest and the most impure parts of the body. Massage is, then, a potentially dangerous activity. It poses a real threat of contagious pollution, which can have a serious impact on caste rank. Recognizing this, Atreya suggests that it is precisely because massage cuts across caste boundaries that it is important to the general condition of the akhara as a whole: “[Reciprocal massage] creates a feeling of mutual love between the wrestlers of an akhara. . . . Status, class and caste distinctions are erased. The poorest of the poor and the richest of the rich come together in the akhara. This creates a feeling of unity (1986b: 27).” Many of the wrestlers with whom I spoke expressed sentiments similar to Atreya’s.

Even where massage structures a hierarchy of rank in the akhara, it is a hierarchy of status and respect based on principles other than purity and pollution. In other words, a young Brahman boy may be seen massaging the feet of a lower-caste senior wrestler. Conversely, a lower-caste boy may walk on the back and neck of a higher-caste wrestling patron. What is more significant than the fact that such events actually take place—for there are professional masseurs who are often of a lower-caste status than their customers—is that wrestlers treat massage as a critique of caste hierarchy. They appropriate it as a way of distinguishing their way of life from the dominant way of life which is structured according to rigid rules of exclusive purity. While many situations in everyday life require contact and interaction between members of different caste groups—barbers who cut their high-caste clients’ hair, for instance—such activities are structured, and conceptualized, in terms of interdependent roles which preempt whatever close physical contact may be entailed. In the akhara in general, but specifically during massage, the caste-based rationale for intercaste contact is explicitly denied.

What is unique about massage, in this regard, is that a critique of caste principles is directly implicated as a factor in the collective health of the akhara. In other words, as Atreya notes, massage creates a healthy state of social unity among wrestlers. Whereas wrestling as an art tends to champion the cause of the individual, massage serves to dissolve the individual into a state of pure, embodied equality. From talking with wrestlers it is clear that general health and fitness depend, at least in part, on the extent to which one is willing and able to merge with this collectivity of feeling. As Atreya and others clearly imply, a person who is concerned with caste status, wealth, and other worldly manifestations of power cannot achieve either success or satisfaction as a wrestler. Consequently, one’s attitude towards caste determines, to some extent, one’s overall physical fitness. A wrestler who is not willing to massage another wrestler on the grounds that he is somehow better than him, is simply not healthy.

This sense of health again makes the point that fitness is conceptualized as a holistic integration of physical, moral, psychological, spiritual, and social elements. In the akhara the basic concept of a healthy person derives largely from a yogic concept of fitness. According to the yogic principles of Yogavasista, worldly, materialistic considerations divert one from the path of self-realization and perfect health. Worldly persons are unhealthy (Atreya 1973d: 39). What is unhealthy about a concern with purity and pollution in particular, and the caste-based body in general, is that it validates rank status as a structuring principle of worldly order. By undercutting caste principles, therefore, massage is regarded as an agency for transcending the illusionary bounds of hierarchy. Wrestlers do not fetishize this issue by turning massage into a self-conscious critique of caste every time it is performed. The power of the act and its implications are felt on a much more visceral, perhaps even psychological, level: a total surrender of the body to a world where sweat and substance mingle without grave negative consequences. What is significant, in any case, is the logic of the relationship between physical contact, caste status, moral virtue, and general health. One might say that massage promotes a form of public health by relaxing muscles as well as social and psychological boundaries.

| • | • | • |

Diet

My purpose here is to analyze the underlying structure of a wrestling diet as a regimen of health. I will show how wrestling dietetics is not only structured in terms of nutrition as a biochemical function but how it is also conceptualized in terms of moral values. In keeping with the general purpose of this chapter I will show how the disciplinary regimen of diet structures the wrestler’s identity as a dimension of his overall health.

Wrestlers are distinguished not so much by what they eat as how much they eat. They are reputed to drink buckets of milk, eat kilograms of almonds, and devour large quantities of ghi per day. However, wrestlers eat many other things as well. Milk, ghi, and almonds only comprise the wrestler’s specialized diet referred to as khurak. Like everyone else, wrestlers also eat vegetables, lentils, grains, fruit, nuts, and other items. With regard to the wrestler’s dietary regimen what is significant is how each type of food is conceptualized within the larger matrix of diet, and how these concepts are applied to the discipline of wrestling.

According to Hindu philosophy, people are divided into three categories based on their overall spiritual cum moral disposition: sattva (calm/good), rajas (passionate/active), and tamas (dull/lethargic). In Ayurvedic theory all food categories are similarly classified ( Khare 1976; Beck 1969). The basic logic of this scheme is that a sattva person will tend to eat sattva food. However, a person can, through design or by accident, change his or her disposition through eating food of a different category.) Khare (1976: 84) and others (Daniel 1984: 184–186; Kakar 1982: 268–270) have cautioned against a too-rigid application of this paradigm of food types to personality disposition. Although both derive from a common base, Ayurvedic healing theory finds application in the manipulation of diet, whereas the philosophical typology of physiology is largely a classificatory scheme. As Daniel has pointed out, the Ayurvedic paradigm is a flexible continuum of tendencies—more or less sattva, more or less tamas—rather than a strict scheme of absolute rules.

For the wrestler the Ayurvedic paradigm provides the basic logic for a very simple rule. Because wrestlers exercise vigorously and therefore heat up their bodies they must eat cool sattva foods in order to foster a calm, peaceful, relaxed disposition. Wrestlers do not always agree on the relative properties of specific foods. Although most will agree on whether something is hot or cold they will often disagree on which of two closely related food types is cooler or hotter than the other. For instance, butter is thought by some to be cooler than ghi. Chicken is thought to be cooler than mutton, but, like all meat, extremely hot as a general rule. The nature of milk is somewhat problematic; cow’s milk tends to be regarded as cooler than buffalo milk, but both are regarded as very sattva on the whole. In order to see how wrestlers conceptualize their diet—which is to say how they work through the particular implications of both nutrition and moral disposition—it is necessary to look at some foods in detail.

Milk and Ghi

In every sense, milk and ghi are the two most important ingredients in a wrestler’s diet. Although he cannot live on ghi and milk alone, a wrestler constructs his diet around them. Generally speaking, they are regarded as the most sattva of sattva foods. Ghi in particular imparts long life, wisdom, strength, health, happiness, and love (Atreya 1984: 21). Because of its eminently unctuous quality, ghi draws out the juices from other foods. It is in this capacity that ghi is able to produce resilient semen. As Atreya points out, eggs produce semen as well, but because eggs are not unctuous in the same way as ghi, their semen and strength flow out of the body as fast as they are produced (ibid: 23). Eggs are also tamas. One of the main virtues of ghi is that while it mixes with and draws out the properties of other foods, it does not lose its own properties through the process of digestion. Its sattva nature remains dominant and resilient.

Ghi is good for nearly everything (Ramsanehi Dixit 1967b). It serves as a perfect, natural health tonic. It may be consumed in any number of ways. Atreya outlines the ways in which it is most beneficial for wrestlers:

After exercise, place as much ghi as you are accustomed to drinking in a pan. Cover this pan with a fine cloth and sprinkle ground-sugar candy on it. Then take some milk and pour it through the cloth into the pan with the ghi. Drink this mixture.

There are a number of variations on this basic prescription. All entail the use of various specific, medicinal, tonic digestive powders referred to generically as churan. In all such prescriptions, churan, ground pepper, milk, ghi, and honey are mixed together in various proportions. Milk is always the final ingredient and is mixed in with the other items (Atreya 1984: 28).

After exercise, take powdered black pepper and mix it in with as much ghi as you are accustomed to drinking. Heat the ghi to a point where it is compatible with your strength (the “heat” referred to here is not only the temperature of the ghi but its latent energy as well). Drink the ghi in its melted form.

There are a number of variations on this prescription as well. Many of the same churan digestives are employed. The main distinguishing feature of this prescription is that milk is not mixed with the ghi.

- In its melted form ghi is also consumed with food. It may be drunk before the regular meal or mixed in with lentils and vegetables or poured on bread and rice.

- One of the best ways to take ghi in your diet is to mix it with dried, powdered nuts and grains. Basically anything which is dry in nature—dry in the sense of being non-unctuous—can be mixed with ghiin this way. Take whatever it is that you wish to mix—almonds, chana, dried peas, pistachios—and grind them into a fine powder. Put this powder into an iron skillet and brown it over a fire. Add some water and continue cooking the mixture until about 150 grams of water remains. Take the iron skillet off the fire and heat up as much ghi as you are accustomed to drinking. Once this is hot, remove it from the fire, take the powdered mixture and add it to the ghi so that it is lightly and quickly browned. Drink/eat this mixture after you have finished your exercise regimen.

- In the evening, take your usual quantity of milk and warm it. Add to this as much ghi as you are accustomed to drinking. Allow this mixture to form into yogurt through the addition of the correct culture. Drink this yogurt after your morning exercises. Be sure not to add any water.

- Grind almonds and black pepper together with some water. Heat up as much ghi as you wish to drink and then add the almond paste to the ghi. Add some sugar and drink this mixture.

- Mix together equal parts ghi, gur (hard molasses), and besan (chickpea) flour. Eat this mixture as a snack after exercise.

- Mix as much ghi as you wish to drink with as much warm milk as you are able to drink. Consume this after exercise. This is different from the other prescriptions in that no digestive tonics are mixed with the milk and ghi (Atreya 1984: 30–33).

In addition to having ghi mixed into it, milk is drunk on its own. Some wrestlers argue that raw milk is best, but others claim that milk must first be boiled. Milk can be processed in various ways in order to make it more or less unctuous. In this way a wrestler can manipulate his diet in order to accommodate the variability of his digestive health. For instance, he may extract much of the butter and drink a low-fat form of milk to which might be added sugar, molasses, or salt. Alternatively, he might add yogurt to the milk and make a kind of high-fat milkshake, lassi, to which might be added fruit, nuts, or cream. Vedi, who has written on the various beneficial properties of lassi, buttermilk, and yogurt, observes, “Cool, fresh drinks play an invaluable role in keeping down the heat which is generated by the active body. Cool liquids [such as milk and lassi] penetrate to the innermost parts of the body and draw out heat in the form of sweat and urine. Of all liquids, milk and lassi are two in which Indians place a great deal of faith” (1973: 17).

Almonds

Whereas ghi produces generalized physical strength, almonds are regarded by wrestlers as a primary source of dam kasi (stamina) and speed (Ramsanehi Dixit n.d.). Almonds are prepared by mashing them into a paste and mixing this paste with milk or ghi. One wrestler explained that almonds impart stamina and strength because they produce energy but are not filling.

Chana

While dried peas, chickpeas, and lentils are commonplace items in Indian cooking, they are also accorded a special place in the dietetics of Indian wrestling. Because almonds are so expensive (75 rupees per kilogram in 1987), chana is regarded by many wrestlers as the poor man’s almond substitute. One of the most common tonic snacks taken by wrestlers is made of sprouted chickpeas.

Chickpeas are soaked overnight in warm water and are then hung in a loose cloth in a warm place. Once these peas sprout, wrestlers eat them with salt, pepper, and lemon. In addition to being a source of energy, strength and stamina, chana is also sattva by nature. Not incidentally, chickpeas prepared in this way are used as the basic prasad food offered to Hanuman and other gods on special days of worship.

The water in which the prasad is soaked is also regarded as saturated with the energy of the sprouted peas. When drunk, this water purifies the blood and also increases one’s strength and store of semen (Saksena 1972: 17).

Many wrestlers feel that chana is saturated with all kinds of beneficial attributes. Western nutritional information has served to substantiate the overall value of chana as a source of vitamins. It is regarded as a source of energy and strength in part because it is so common and cheap. The idea is that everyone can afford chana and therefore everyone can be strong and healthy. Saksena writes: