Tantrism As A Religious Mode

There is a substantial literature discussing aspects of the Tantric tradition in Buddhism and Hinduism (see, particularly, the synthesis by Gupta, Hoens, and Goudriaan [1979]). Tantrism has been characterized as an "historical current" within the larger South Asian tradition, a current that is relatively easy to recognize in its manifestations and notoriously difficult to define. "The extremely varied and complicated nature of Tantrism, one of the main currents in the Indian religious tradition of the last fifteen hundred years, renders the manipulation of a single definition almost impossible. There is, accordingly, a general uncertainty about the exact scope of the word" (ibid., 5). These authors attempt, however, a definition, which will serve as a useful introduction to Bhaktapur's Tantrism (ibid., 6 [emphasis added]):

In our opinion, it is mainly used in two meanings. In a wider sense, Tantrism or Tantric stands for a collection of practices and symbols of a ritualistic, sometimes magical character (e.g., mantra, yantra, cakra, mudra, nyasa . . .). They differ from what is taught in the Veda and its exegetical literature but they are all the same applied as means of reaching spiritual emancipation (mukti ) or the realization of mundane aims, chiefly domination (bhukti ) in various sects of Hinduism and Buddhism. In a more restricted sense, it denotes a system, existing in many variations, of rituals full of symbolism, predominantly—but by no means exclusively—Sakti, promulgated among "schools" . . . and lines of succession . . . by spiritual adepts or gurus . What they teach is subsumed under the term sadhana , i.e. the road to spiritual emancipation or to dominance by means of Kundaliniyoga[*] and other psychosomatic experiences. . . . It is important to remark at this point that the true Tantric sadhana is a purely individual way to release accessible to all people, women as well as men (at least in theory), householders as well as ascetics . At present the practicers (sadhaka ) of the Tantric system are mainly people who live an ordinary life within family and society. But beside this ordinary reality, they try to come into touch with a higher stratum of divine reality by a course of identification with their chosen deity who Is usually the Goddess.

Elsewhere in South Asia the individualistic, anti-Brahmanical, anti-social-structural aspects of Tantrism, although they influenced renouncers of Hindu society (see, for example, fig. 18) and those who tried to manipulate the world through magical power, became for most

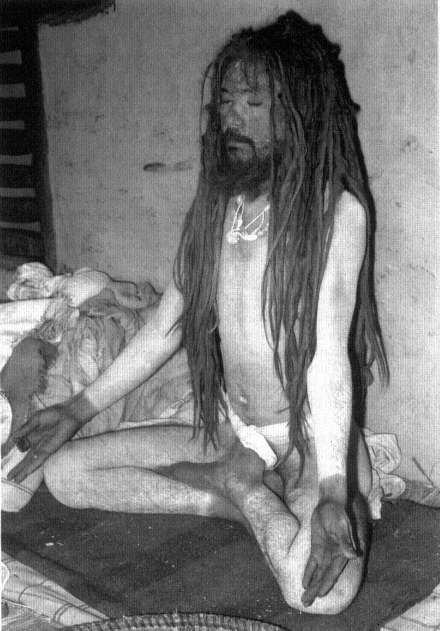

Figure 18.

Outside the city. A wandering Indian sadhu doing yoag on a public

porch in a mountain village.

practitioners—for those who "live an ordinary life within family and society," that is, within the Brahmanical order—comfortably bracketed into safe and nondisruptive contexts (ibid., 32):

The Kularnavatantra[*] states that anything which is despised in the world is honorable in the Kula [a particular school of Tantrism] path. On certain occasions, the texts even express a preference for anything which is associated with low social standing or with the breaking of taboos. . . . Of course, this was an important factor in creating for Tantrism its bad repute with the orthodox. But anti-caste statements should never be read outside their ritual context. Returned into ordinary life, no high caste Tantric would think of breaking the social taboos. One might even argue that the predilection for contact with low-caste people, especially women, in a ritual environment served to render the high-caste practicer still more conscious of the violent breakthrough of his ordinary situation which he had to make in order to proceed on the way to spiritual emancipation. Seen in this light, the ritual egalitarianism of Tantrism in practice acted as a caste-confirming and class-confirming force. One can compare the confirmatory and stabilizing role of festivals like Hob or Sabarotsava, during which caste or class relations are temporarily eliminated.

Bhaktapur has gone further in the use and transformation of Tantrism than as an exciting and cathartic antistructural fantasy for upper status men—although that is still one of its important uses. It has transformed the Tantrism of transcendence of Brahmanical order for the purposes of individual salvation and individual power and put it to the use of the civic order, in so doing complexifying that order. Legendary accounts of the capture of Bhaktapur's protective deities, the Nine Durgas (chap. 15), vividly portray this double movement. The stories tell how the demon-like deities who make up the group once lived in a jungle outside of Bhaktapur where they killed and ate the innocent passers-by whom they happened to encounter. Eventually the gods were captured by the spells and wiles of a powerful Tantric practitioner. He took them into the city, put them in a secret room in his house, and, using them for his own private amusement, "played with them" and made them dance for him. But then through the interference of his wife—representing one of the central symbolic mediators from private masculine pleasure to social order—the demon deities escaped his private control and fled the house. The Tantric practitioner was able to recapture them, but by now they had taken measures to prevent his taking them back into his house. Now unable to use them for his own purposes, he, in a compromise, forces them to pledge to protect the public city, to use their power against those external forces of disruption that they originally repre-

sented in themselves. The Tantric expert who presided over this transition (who in some versions is different from the magician who originally captured them) was, significantly, a Rajopadhyaya Brahman. However, once the secret was out, once the dangerous, blood and alcoholic spirit-swilling, order-destroying, and polluting[1] gods were out in the visible public space of the city, special kinds of priests, Acajus (chap. 10) had to replace the Brahman to deal with them in public—although the Brahman's descendants would continue to be engaged with them in more esoteric arenas.

For Bhaktapur's "Newar Brahmans" (chap. 10) and Ksatriya-like[*] Chathariya and Pa(n)cthariya groups, Tantrism is not only, as it was for the Tantric master who captured the Nine Durgas in the self-indulgent time before his wife's interference, a source of private fascination but also central to the worship of their partilineal lineage deities. Their exclusive right to Tantric initiation is, in fact, one of the most important markers setting them off from middle-status and low-status groups in the city. This "gentrification" of Tantrism existed in other parts of South Asia. "The study of later Tantric literature seems to reveal an ever tightening grasp of Brahmans and other intellectuals on the movement—or, as one could as well say, an ever greater hold of Tantrism upon the traditional bearers of Indian literary culture" (Gupta, Hoens, and Goudriaan 1979, 27). This elite domestication existed and exists in a somewhat uneasy relation with Tantrism's asocial and, in fact, antisocial central thrust, as well as with the low origins and family connections of its central deities.

The problem is clarified by the situation of the dangerous deities in non-Tantric communities. In a consideration of ritual in the Indian village of Konduru in Andhra Pradesh, Paul Hiebert made a distinction between the "high religion" of the village and its "low religion." The "high religion" centers around the benevolent Hindu gods of the "great tradition." Its priests are Brahmans (for the higher castes), the offerings to the gods are vegetarian. The "low religion" centers around "regional Hindu gods and local gods linked to Hinduism" (1971, 133). Hiebert further notes (pp. 135-136):

Chief among these [supernatural beings] are the local and regional goddesses who reside in trees, rocks, streams and whirlwinds and are enshrined in crude rock shelters in the fields, beside the roads, and in the home. Capricious and bloodthirsty, they demand the sacrifice of animals to satisfy their desires; therefore, the Brahmans refuse to serve them. Their priests are Washermen, Potters, and Leatherworkers. . . . All villagers fear their anger

which can bring disease and death to those who neglect them, blight to crops, fires to houses, barrenness to wives, and plague and drought to the village. Even the local Brahmans who deny their existence take no chance and send their offerings by the hand of a family servant to be sacrificed to the goddesses of their fields.

This village arrangement reflects the hierarchical predominance of "Sanskritic" over the other deities in Indian village pantheons that we noted in the last chapter, but it also emphasizes the social peripherality of such "local and regional" deities whose worship and characteristics are those of Bhaktapur's dangerous deities. Even as the status of the dangerous deities—who have been, like the Nine Durgas, captured and taken into the city, albeit in an ambiguous incorporation—has changed in Bhaktapur, so has the social status of their cult and their priests. Yet, the Indian village situation clearly suggests the contradictions and tensions in the apparent urban respectability of these deities in Bhaktapur. The Newar Brahman, the Rajopadhyaya Brahman, has, as we will see below and in chapter 10, important Tantric functions, but these are hidden within private, esoteric arenas of the city's worship. Public Tantric worship is usually done by other priests, the Acajus (which has sometimes led to the erroneous statement in descriptions of the Newars that they are somehow the "Tantric priests" in some sharp opposition to the Brahmans as "Sanskritic priests"). As we will see in chapter 10, the interlocking roles and relations of Brahmans and Acajus in relation to Tantrism and ordinary Hinduism in Bhaktapur are complex. As he is in Hindu communities everywhere the Brahman is a central priestly figure in the "ordinary" Hinduism of Bhaktapur. In relation to the Tantric component of the city religion, however, he has special functions—as guru , giver of mantras , officiant at some Tantric ceremonies for clients, performer of his own private and family Tantric ceremonies, and as priest at the Royal temples of the dangerous deities (particularly Taleju)—which make him, the priestly master of Bhaktapur's urban, civilized Tantrism, a much more complex figure than the ideal Sanskritic Brahman.