Bhaktapur's Pantheon As A System of Signs

Underlying our presentation of Bhaktapur's deities and supernatural figures is the assumption that the many individual deities, objects, and creatures we have discussed are imagined, created, and arraged in such a way that they can be comprehended by people in Bhaktapur and that they are able to make, each in its own way, their special contribution to the representation, creation, and maintenance of the city's mesocosm. We have noted that the active members of the pantheon are, for the most part, selected from the great South Asian historical and areal lending library of god forms. There are both economic and semantic reasons for the selection.

In a study of the meaningful (as opposed to "known about") deities in the "personal pantheons" of a Chinese and a Hindu informant,

Roberts, Chiao, and Pandey (1975) found that although the Chinese informant knew in some detail about some sixty deities and the Hindu informant about more than one hundred, their "meaningful god sets"—the ones that had "personal significance and salience" for them—was, for each, fifteen deities. After examining some of the aspects of meaning by which each informant compared, contrasted, and sorted the members of his pantheon, they concluded that "Meaningful god sets appear to be symbolic small-group networks, with believers ordering their thoughts about their gods in terms of a relatively small number of major dimensions. Since they seem to have few members, it is probably the case that every god within this limited number must carry his full religious and psycho-cultural weight" (Roberts, Chiao, and Pandey 1975, 145f.). The number of active gods in Bhaktapur's urban pantheon that are of general urban importance are also limited in number, although there are more of them than the fifteen in those two sample private meaningful pantheons.[68] There are somewhat more than forty if the ghosts and spirits are included, and less than forty without them. That quantity is probably small enough so that each deity may carry a "full religious and cultural weight" for city dwellers. This is to argue, following Roberts et al., that the civic pantheon is a "meaningful god set" to the city's individuals , for the numerical constraint has something to do with individual cognitive capacities. However, the gods' identification, meaning, and use are made easier by their location in a few more general meaningful classes . Those classes, in fact, contribute importantly to the deities' differential "religious and psycho-cultural weight" in the public urban order.

In his summary work on ancient Greek polytheistic religion, Walter Burkert writes of Greek ritual that "the same repertoire of signs is employed by various groups in various situations" (1985, 55). The Greek pantheon, in contrast to, say, the vast Hittite and Babylonian pantheons, is distinguished by its "compactness and clarity of organization . . . the Greek gods make up a highly differentiated and richly contrasted group." And, he adds, "The primary differentiations are taken from the elementary family groupings: parents and children, male and female, indoors and outdoors" (1985, 218).[69] If a common "repertoire of signs" is to be put to concrete uses in a community and thus to be understandable and learnable, it must, as the paper of Roberts and colleagues suggests, be sufficiently compact and differentiated for such uses.

There have been some anthropological approaches to Hindu pantheons as "repertoires of signs" (Babb 1975; Wadley 1975; Harper 1959) in comparatively simpler Hindu communities which will later provide some useful comparisons with Bhaktapur. As Babb put it for the area of Madhya Pradesh that he studied, "The pantheon is not a haphazard congeries of gods and goddesses but a system of symbols that formulate a view of reality. The pantheon symbolizes a world, the world in which ritual action takes place" (1975, 215). When we consider a deity (or any other type of cultural object or event) as a "sign" and as a member of a domain of signs, we are interested in its meanings and uses to a particular community of sign interpreters and its meaning for certain purposes—here, as throughout this book, for the most part for the purposes of urban integration. The deity's history is of interest in such an analysis only as it is "living" and informs present meaning and use. In a sense "extra" history clings to it, however, and makes it something more than present systematic community usage may require[70] and gives it a creative potential for some emerging future conditions.

But to what do those meanings cling?

Bhaktapur's Pantheon As A System of Signs: Some Notes on Idols

At the turn of the nineteenth century, the Abbé Jean-Antoine Dubois, carefully considering the question of "idolatry," wrote that Hindu idolatry was "grosser" than pagan idolatry, in that while the pagans worshiped fauns and naiads, the beings who presided over the forests and the rivers, Hindus worshiped the "material substance itself, . . . water, fire, the most common household implements" (1968, 548). "Idolatry" here means the violation of the Judeo-Christian-Islamic profoundly transforming program and dictate to pagan and "primitive" religions to worship the distant creator rather than the environing creation.[71] But, Dubois continues, "It is true that they admit another kind of idolatry which is a little more refined. There are images of deities of the first rank which are exposed to public veneration only after a Brahman has invoked and incorporated in them these actual divinities. In these cases, it is really the divinity that resides in the idol, and not the idol itself, that is worshiped" (1968, 548). This is what sophisticated—and probably most—people in Bhaktapur still hold. This does not allow us to dismiss the "idols" themselves, however, the "idols" that, as Dubois reminds us, embody specifically "deities of the first rank."

The "idols" are, that is, only one of several kinds or classes of forms of deities. Those classes of forms are centrally important for carrying, each in its way, an important category of significance. Within the class of "idols" their members' differentiated identities are constituted by their own iconographic components—the gestures, postures, paraphernalia, associated "vehicles," crowns, arrangement of hair, and so on, which are the subject of iconography, and which serve to identify the particular divinity. These components, which turn, for example, a carved piece of stone into an adequate representation of Siva, are for the most part neither our concern nor the concern of the people of Bhaktapur once the minimal adequacy of the image to represent what it is supposed to represent has been assured. The central problem in the urban uses of the pantheon is to know that an image is or is not Siva. The constituting parts of the image are of concern only where they may have some direct semantic import and thus contribute to the meaning as well as the identification of the image, and in the rare cases where the iconographic details of a particular version of a divinity may give the image one rather than another of its possible significances and uses.

Bhaktapur's Pantheon As A System of Signs: Classes of Meaningful Forms

Each of Bhaktapur's urban supernaturals is from one point of view a somewhat fuzzy clump of ideas and feelings and urges to action in peoples' minds. These are usually manifest in or focused on concrete material objects or, in the case of spirits and ghosts, an imagined object. Whatever the ideas, emotions, and calls to action understood to be associated with these objects, it is the concrete objects that exist in some sort of external space, make an impact on the senses, and have perceivable boundaries. Many of these objects can be manipulated, placed and fixed in space or moved through it and used as central references for action. The object is a part of the meaningful deity considered as a "sign," but it is important for our purposes to distinguish it from other meaningful aspects. It is something like what Charles Morris (1938) called a "sign vehicle." The sign vehicle, in concert with the other sorts of meanings that it focuses makes up a sort of "god sign," which, following the semiotic analogy somewhat further, can be combined and contrasted with other such signs in various ways making possible an infinite variety of symbolic statements.

The meaning of a city god, like all "natural" sign systems (in contrast

to logically constructed ones) is a multilayered, context-dependent, and sometimes ambiguous fabric. The god-bearing objects and man-made images not only carry great quantities of history, myth, and legend but also absorb the implications of their uses, their relation to status, space, time, and specific symbolic enactments, and that absorbed meaning, in turn, makes them fit for new relations from which they again absorb meaning in a continuing process. However, the objects and images are not just sponge-like units absorbing any meaning of placement and use, Humpty Dumptyish terms that can mean anything one chooses to make them mean. Certain aspects of their meaning are more central, less fluid than others, and give to the gods as signs their adequacy to be used or located in certain ways. This can be called, for want of a better term, their "primary contribution" to the field of meaning. These "primary" aspects include the major legendary characteristics ascribed to the god in Hindu tradition. Much of their "primary contribution" comes from very general aspects of their form, however, and that form is at the same time—and in specific relation to its context-resistant contribution to their meaning—an important aspect of their classification.

The formal aspects that may be used to sort the pantheon into classes of deities are different from those that differentiate the members of the various typological groups. The members are usually differentiated by conventional iconographic features. Hierarchical relations among members, where they obtain, may be indicated by relative features—comparative size or position (right vs. left, center vs. periphery). The classes of gods are distingusihed by neither conventional iconographic signs nor relation, but by discontinuous and "directly meaningful" (rather than "conventional") contrasts.

The classes of deity differentiated by "directly meaningful," easily understandable, contrasts of form are those fundamental contrasting sets we have discussed throughout the chapter, the sets that are put to extensive symbolic use in the city. Let us recall those classes, rearranged for present purposes in an order different from that in which we presented them above. These classes are: astral deities, ghosts and spirits, stone deities, and major civic deities (of which there were two sub-classes, benign and dangerous). The other deities we discussed (e.g., royal pilgrimage gods, household gods) belong in their form to one or another of these groups.

The contrasts that serve to sort the types of supernaturals and bear on their meaning and use are in the following dimensions:

1. Proximity.

Proximate forms are present in city space (including its bordering outside where they may be directly encountered, and are in contrast to the distant impersonal forces represented by the astral deities, who are for the most part, the distant heavenly bodies.

2. Materiality.

Among the proximate beings are those having a fixed material form, which may be contrasted with those whose forms are immaterial , the ghosts and spirits.

3. Artifice.

Among the beings with material forms, there are those whose forms are humanly worked in contrast to those whose forms are aniconic "natural " forms.

4. Ordinary versus uncanny humanly worked forms.

Among forms that are humanly worked there are the ordinary forms , whose imagery is closely derived from the forms, logic, and relations of the social world of objects and persons, in contrast to the dangerous forms , whose imagery is derived from dream-like or hallucinatory forms, logic, and relations. A diagram of these contrasts indicates certain aspects of this branching typological schema:

The main movement of this classification as the contrasts at each level are isolated—the right-hand terms above—is a progressive movement toward the everyday moral life of the city, ending with the ordinary deities, those deities that are thought of and dealt with as "persons," and who represent community ideals and norms. They are proximate, material, shaped through culture, and not demonic. Let us recall some of the aspects of the formal sets distinguished by these contrasts to suggest their contributions to meaning.

1. Proximate versus distant.

This first distinction separates the astral deities from all the rest. The astral group are essentially impersonal cosmic forces. Their movements are regular and they provide the external rhythm and tempo that must be understood and adjusted to, as opposed to the manipulations and avoidances possible within other realms. This is true of both the calendar-determining phases of the moon and movements of the sun and the influences on "luck" of the whole astral set. The function of the astrological expert, the Josi, is to map the exact state of the astral realm and help individuals and priests adjust to it. Most ritual activities addressed to other kinds of deities are fitted in various ways to one or another indication of cosmic rhythms given by the astral bodies. Although they may have some iconic representations, the astral deities are embodied in their existent forms as distant astronomical forms and events in the skies. In contrast to the astral deities, all the other divinities and ghosts and spirits are immediately present and closely encountered in and around the city, and in contrast to the regular clockwork movements of the distant deities, the proximate beings have minds and passions and whims and thus have some freedom of action, make decisions, and can be influenced by individuals in one way or another.

2. Material versus immaterial.

The proximate beings can be divided into those that are embodied in some concrete form for most city purposes, and those that are not so embodied, which remain "immaterial." The nonembodied forms are the spirits and ghosts. The identification and classification of the nonembodied forms are, as we have noted, comparatively vague. These beings have relatively little cultural construction, local tradition providing only vague identifying sketches. They are not objects of any cult or community religion, and are the only beings we have listed here who are not in one or another context referred to as dya : or "gods." They are of personal and immediate local concern only. They are only rarely, fleetingly, and haphazardly encountered, although they provide the basis for many exciting accounts. The work they do for the community is to give some shared name and vague form to a range of vague private encounters, perceptions, and psychological states. The embodied beings, in contrast, constitute the working civic gods. Because of their embodiment in material objects they can be perceived in common, and can be related to significant space, either as fixed in a particular spot or carried through some particular area. The embodied deities are public objects, and as they are objects that affect

the senses in a discrete and controllable way, they serve perfectly as civic "sign vehicles."

3. Worked versus natural.

The embodied material beings can, in their turn, be sorted into two groups, "worked"—those that are given some conventional form through the efforts of artists and craftsmen following the traditional canon for the production of valid images—and "unworked"—naturally occurring objects that are credited with embodying a divinity. The unworked objects of importance in the public city religion are, for the most part, stones, almost always embedded in the ground. These unworked stones represent in local conception as they do in their form something intermediate between the formless spirits and the crafted deities, having both spirit-like features and god-like features. The gods they represent are vague in their conception and classification when compared to the gods of the worked images. The stone gods are never portable, and thus never used to mark out an area through their movements; they mark or protect fixed boundaries between some socially differentiated interior unit and its less social or nonsocial outside. They belong mostly to that vague outside, and mark the outer, the relatively nonsocial face of the boundaries at which they are fixed. They share some features with one division of the worked divinities to form a crosscutting group of "dangerous" divinities.

4. Benign versus dangerous.

When we turn to the divinities who are represented by humanly worked and formed images, icons, we enter the realm of the major gods of Hinduism, those that are usually considered as constituting a pantheon. These gods all have anthropomorphic images, although some part of the image, usually the head, may have an animal form. We are now encountering figures that not only are sentient beings but also have at least external human characteristics. They represent a movement away from uncanny beings, toward something more understandable—understandable, that is, in a particular way, the way we understand humans as "persons." It is this group that is the focus of most calendrical festivals, whose myths, legends, and relationships order most ritual action. These divinities have houses and temples, and may be fixed in a position in space or be carried in festival processions or embodied in human agents. They are present in the city at rest or in movement as anthropomorphic, embodied beings, very much as the citizens of Bhaktapur are so present.

This final division of classes of divinity is within the set of culturally

worked anthropomorphic gods. Here the distinguishing formal contrast is the appearance of the images themselves. One set has various features that suggest emotionally driven dream-like images, features that escape from the constraints of ordinary everyday reality. They include fangs, cadaverous bodies, bulging eyes, garlands of decapitated heads or skulls, mantles of flayed human skin, and multiple arms. The arms carry human calvarias (understood to be drinking cups full of human blood) and various destructive weapons. The female forms of this type (and not the male ones, which, when shown as being sexually aroused, maintain their demonic forms [fig. 17, chap. 9]) included images of exaggerated seductive sexuality, with exaggeratedly rounded, youthful faces, hips, and breasts. Their hands, however, bear the same objects as those of the frightening figures. Both versions—beautiful and horrible—may be conceived of as dream-like and hallucinatory images. This group represents the "dangerous anthropomorphic gods"—"dangerous anthropomorphic gods" because the group of "dangerous gods" also includes the stone gods, with whom these deities share some characteristics. These anthropomorphic dangerous gods are the foci of many city festivals. They and the associated stone gods are the major symbolic resources for the marking of significant city space. The anthropomorphic dangerous gods have potentialities beyond the stone gods. They, like the benign set, may be arranged in differentiated sets; they can move through space, and they thus allow for differentiated and specialized statements in their use in the various symbolic enactments that mark, relate, and protect various units of the city.

With the group of culturally crafted anthropomorphic gods, we begin to have identified individuals who are embedded in characterizing relations with similar beings. We have something like a socially created, morally controlled person . The dangerous deities, however, as we have noted in earlier sections, are uncanny persons; they are too dream-like, shifting and flowing in their forms and in their logical relations with each other. When we have followed our main axis from distant to proximate, to materiality, to anthropomorphic form, and finally to ordinariness , however, we are at the end very close to full "persons," as defined by the roles, needs, and possibilities of a social community. These residual "ordinary" anthropomorphic gods are heroic persons, with extraordinary—albeit not unlimited—powers and with graspable minds. This is manifest in their prevalent imagery as idealized human types. Even if they are partially animal in form, such as Ganesa[*] , Hanuman, or Visnu's[*] vehicle Garuda[*] , they are humanized animals, in con-

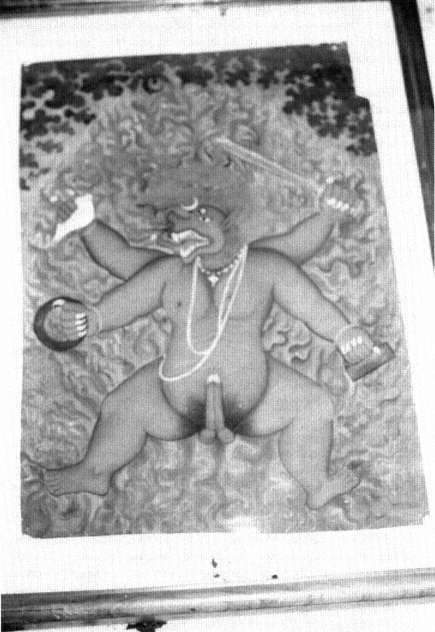

Figure 17.

An esoteric image of a Bhairava.

trast to the frequently bestialized humanoid forms of the dangerous anthropomorphic gods. They represent the moral interior of the city and both represent and are models for the moral dimensions of human relations (above all, those of the household and other intimate relations) and of the self.

Walter Burkert argues that the Greek Homeric gods move beyond the anthropomorphic gods of the Near Eastern and Agean neighborhoods of Greece. Those gods "speak and interact with one another in a human way, . . . love, feel anger, and suffer, and . . . are mutually related as husbands and wives, parents and children." But the Greeks, he says, add something to this. "The Greek gods are persons , not abstractions, ideas or concepts. . . . The modern historian of religion may speak of 'archetypical figures of reality,' but in the Greek, locution and ideation is structured in such a way that an individual personality appears that has its own plastic being. This cannot be defined, but it can be known, and such knowledge can bring joy, help, and salvation. These persons as the poets introduce them are human almost to the last detail" (1985, 182-183 [emphasis added]). Jean-Pierre Vernant, on the contrary, asserts that "the Greek gods are powers, not persons" (1983, 328). He argues this on the basis of their difference from what he takes to be the essence of social persons—namely their being as "autonomous focuses of existence and action, ontological units." Claiming that "a single person cannot be several," he calls attention to the various states and conditions referable by term such as "Zeus." However, this does not affect the argument that in particular temporal and spatial contexts and uses these gods are "persons" in a way that the members of some other pantheons are not, and that this quality as manifest in these contexts is of considerable importance for understanding the ancient Greeks and their religion. It is their person-like aspects that most clearly locate the forms, meanings, and uses of the ordinary gods as members of a particular class in Bhaktapur's civic pantheon. When, in contrast, a member of this set is considered in historical perspective, and its uses in other settings and conditions and in differently arranged pantheons are all added to the identity of the divinity, another type of figure, of great mythic complexity, emerges. As we have noted, such histories surround all the gods of the pantheon but are distant background to the choices and simplifications that must be made for the god's synchronic civic uses.

"Person" refers to a universal social invention, "someone" as the

legal definition has it, "who is capable of having rights, and being subject to duties and responsibilities," that is, a relatively fixed actor in the give and take of a moral system. Not all individuals in a community are "persons" in this sense; infants and often the mentally ill and defective are not. The benign gods have many of the characteristics of persons in this sense. They look like humans, and their special differentiating aspects are all social. They are embedded in and defined by social relations, out of which a larger community of related divine individuals is built. Their relations to each other are in part moral, matters of understood obligations and limits, and in part passionate. But their passions and motives—annoyance, rage, lust, compassion, respect, and fear—are ordinary social ones. The benign gods are in large part fixed in their forms and in their relations, and usually work things out within the constraints of logic and ordinary reality to which is added a superhuman (but limited) power that they use in times of special need. Like ordinary persons, they are subject to pollution (compare the discussion of the Nine Durgas in chap. 15), which indicates that they must, like all mature citizens of Bhaktapur, take care in order to maintain their social definition as persons (chap. 11). The dangerous gods have no such concern.

The benign gods as persons represent, as Babb has proposed, "certain key values of Indian civilization" (1975, 224). But they represent not only ideal values but also aspects of "normal" behavior, that which is tolerable for humans. What they do not represent (except transiently in the history of that generative and bridging form, Siva) is "insanity" and other modes of operation and understanding of the mind peripheral to the "person." This is done by the dangerous deities in various ways. As representations of the ideal and "the human," the benign deities become foci of identification and guides for proper behavior and moral standards, and also for tolerant understanding. Their soteriological functions have to do with reward or punishment of the atma , the particular spiritual entity that is for most people closely connected with the idea of the self and its persistence after death. This reward or punishment is based on moral performance within everyday life and with the proper devotion or "service" to the god and, in marked contrast to the effects of encounters with the dangerous gods, with inner intentions as well as external behavior. The benign gods, like all the gods, are subject to ritual manipulation. But their proper devotion and ritual manipulation consists primarily of a mimesis of honorific and respectful behavior, in the course of which they are offered the same honor, hospi-

tality, gifts, and services that would please any honored guest or person of high status. Such rituals reinforce and reaffirm the worshiper's social relation to the benign deity. All this does and can go on only within a rational, dependable world. These gods are "ordinary" and not "dangerous" precisely because they respond dependably to anyone with adequate social and moral skills, anyone who has, in part with their help, become a competent person by Bhaktapur's standards.

For other tasks and meanings Bhaktapur employs other types of divinities, divinities who are much more peripheral to the moral world of persons than the ordinary gods, and who thus represent other realms and ideas and who must be dealt with in other ways. The dangerous anthropomorphic gods vividly represent this nonmoral realm precisely because they have some characteristics of persons—names, forms, and anthropomorphic embodiments. They are radically peculiar and unacceptable persons, however, persons in flux—to recall Vernant, they are not quite "ontological units." They are outside the constraints of both logic and morality that are the essence of true persons. They represent the bordering outside of the ordinary world in a variety of ways—they are related to the forces and forms of "nature" beyond the city, wild and dangerous but at the same time vital, and also to certain psychological modes—dream, insanity, and those passions and impulses (e.g., cannibalism) that are beyond what are acceptable even to a tolerant view of what a person is or should be. As they do not operate through moral interactions and manipulations, they operate in the only other available mode, through power, and that is the way they, in turn, must be dealt with. This constellation of characteristics used to portray the hinterlands of any moral community has many familiar echoes throughout the world,[72] but the uses of the dangerous gods have a particular development, force, and legitimacy in Bhaktapur. In contrast to many other Hindu communities (below), the dangerous gods have a special status in Bhaktapur as legitimate and high-ranking members of the pantheon, and as Tantric gods they are (as we will see in the next chapter) in many ways the foci of aristocratic and royal worship.

The dangerous deities represent not only the nonmoral exterior of the city but also the relatively nonmoral aspects of the exteriors of various of the city's component units. In some contexts, they are associated with individual's bodies and, particularly, with danger to those bodies in contrast to people's selves, souls, or "personhood," all associated with the benign moral deities. Most generally the dangerous gods protect the perimeters of the community, of its components, and of its

members, within which the ordinary moral life, represented by the ordinary gods, can go on, while at the same time representing aspects of the external dangerous forces. In protecting the boundaries of moral units and civic spaces, however, they also represent and protect such units as a whole . It is in this way that they can be made to represent the city as a whole, a lineage, guthi , or a neighborhood.

The use of dangerous deities as the representatives of a moral maximal unit warrants more comment. Let us recall the emergence of Devi in the Devi Mahatmya . When the world of the gods is threatened by danger from the Asuras—that is, when that world emerges as an entity precisely and only because it is set against a dangerous, contrary world—the Devi arises. She uniquely represents the world of the gods, even though she is not a "normal" member of that world. if she were, she could not protect them. She can protect them only by sharing in the nonmoral power of the external forces she has to defeat. In analogous ways Bhaktapur uses nonmoral deities to represent, as well as protect, moral units.

There is another important aspect of the use of nonmoral dangerous deities to represent a moral unit. They protect that unit in a very real way (as we will discuss in later chapters, particularly in relation to the Nine Durgas in chap. 15) by helping to ensure the adherence of its members to its moral system. The dangerous deity, usually a goddess, in concert with the meanings of blood sacrifice offered to her, represents the destruction that will overtake members of a group if they violate their adherence to the moral system and moral solidarity of the group. She binds members into the group as well as defending the group's boundaries and representing it as a whole.

Insofar as the dangerous deities themselves represent the kinds of external dangers they protect against, they must first be captured in order to be put to work for the community. As we will see in later chapters, this is done in local legend through the Tantric power of exceptional individuals. For ordinary individuals the dangerous deities can be controlled, albeit somewhat tenuously, not through social deference and good behavior as are the ordinary gods but through an individual's initiation into secrets of power, and the use of spells (mantras ) and, above all, through the use of one of the most important ritual resources in Bhaktapur, blood sacrifice, whose meaning in relation to the dangerous gods we will discuss in later chapters. Most of the time one deals with these powerful and erratic deities by trying to avoid them, or not to anger them or—if one has reason to assume that they

are angry—asking forgiveness and making restitutive offerings, even if (in contrast to the moral deities) they may have become angry "without cause." As the dangerous deities do not represent moral values, they cannot be, as the ordinary deities are, models for ideal or tolerable behavior. Their psychological functions for individuals, like their uses for th city, are quite different from those of the benign deities with whom they contrast within the formal supernatural class of humanly worked deities.

A few classes of deities differentiated among themselves by a few structural features do, as classes, much of the work of organizing realms of meaning in Bhaktapur. Their contrasts use kinds of meanings—near versus far, vague versus clearly formed—which are easily apprehended, and require minimal special cultural knowledge. The situation changes radically in relation to the organization and uses of the differentiated supernaturals within the classes of deities.

Bhaktapur's Pantheon As A System of Signs: Distinctions Within this. Types of Gods

The differences among the sets of gods, essentially the differences in their mode of representation, are, we have argued, based on certain contrasting structural features and are the basis for much of their meaning. Within the sets the distinctions are not the distinctions of classes or types, but, for the most part, distinctions among individuals . These distinctions are generally made on the basis of the clusters of iconic signs that identify each individual, usually redundantly—any one of several features will sufficiently identify the deity—as long as the other features are not too anomalous. These differentiating features are the usual ones emphasized in treatises on the iconography of the Hindu god images[73] —crowns, vehicles, markings on foreheads, objects held in the hands, vehicles, aspects of dress, color, and the like. Without considerable interpretation based on knowledge of their myths and histories, the meanings of many of these features—beyond their identifying uses—may (with exceptions to be noted below) seem more or less arbitrary as direct indications of the paricular individual's present meaning or use. The individual stone deities (helped by some associated markings) and most of the astral deities are identified by their positions.

In most sets of deities the different deities—Indrani[*] , say, in her contrast to Brahmani—do not contrast in their general meaning and use, in

which they are often identical, but in the portion or component of some larger whole made up of equivalent or near-equivalent parts—such as the mandalic[*] segments of the city, the aspect of the full Goddess emphasized for some special purpose, the days of the week of astrological concern, or the set of all tutelary phuki deities—which they stand for. Each of these member deities in a set must be identified as an individual, but an individual whose particular individuality has little differentiating significance beyond their relevance to some specific sector of space or time or society. Often people who are not specially concerned with one of these individual member deities may not be entirely certain as to which member of the group they are, and may misidentify them or identify them with some lumping collective term.

The relation of deities within groups insofar as they mark equivalent divisions of space, time, or status is generally "horizontal" and more or less equal, but there are also some hierarchical relations within groups. These are sometimes indicated by size (anthropomorphic statues of an ordinary god and his consort usually depict him as larger (see fig. 12); the masks of Mahakali and Bhairava are larger than the less powerful figures in the Nine Durgas group (see color illustrations), and so on), or by central versus peripheral positions. (Tripurasundari is at the center of the city mandala[*] , the vehicles of Siva and Visnu[*] may be placed at the periphery of a temple, they at its central axis.) Above and below may also be used to indicate relative status, with a god's vehicle sometimes shown as kneeling at his feet, or placed below them. Among the benign gods the relation of the male gods and their consorts is shown by the consort being placed to the male god's left. Such relative features are not used in contrast between the different classes of gods who do not have hierarchical or consort relations across types.

Against these general features of the differentiation of the members of sets there is a very significant exception within one particular set, the benign deities. Within the set of the ordinary gods directly understandable implications in the images become, as they were in the case of classes of deities, once again salient for a differentiation of the meanings represented by each deity. Here the distinguishing features are the dusters—among the background of presently otherwise meaningless identifying iconographic features—which identify social behaviors and qualities. The tiger skin and yogic costume of Siva in some of his moods, the modest beauty of Parvati, the cuteness of the benign Ganesa[*] , and so on, are such easily apprehensible meaningful features.

The benign deities in contrast to all the others are persons, and their forms help remind people of the kinds of persons they are. There local uses are rooted in these meaningful personal differences.

Bhaktapur's Pantheon As A System of Signs: Some Contrasts With Other Hindu Systems

A comparison of the organization of Bhaktapur's pantheon with reports from other Hindu communities highlights some of Bhaktapur's special features. Edward Harper, in a study (1959) of Totagadde, a village in Mysore State, found a local hierarchy of three levels of supernatural beings. The highest level were the familiar "vegetarian" gods of the major Hindu tradition ("Sanskritic gods"). These gods, locally called "Devarua," are "generally iconographically represented." They are most frequently worshiped so that the devotee will obtain punya[*] ("merit"). This may be in the hope of good fortune in this life, or a good fate after death (1959, 228f.). We recognize in this group some of the characteristics and uses of the "ordinary" segment of Bhaktapur's pantheon. Harper's second class of deities, second in a hierarchy of purity, are locally called "devates. " These gods demand and accept blood sacrifices. They protect the village in various ways. They patrol the village boundary or guard designated parts of the village. They also protect various social segments, families, and lineages in the village. Some are attached to houses, where they "protect adults, children and livestock from spirits . . . who cause minor illness" (1959, 231). The same class of deities can possess individuals, and cause illness. While the first group of deities are responsible for trouble only in the sense that they withhold aid that might have been granted, this class may actively cause harm, and part of their worship is intended to prevent this. These deities resemble in nature and use Bhaktapur's dangerous deities, but there are important differences. For the Mysore village these "local gods" do not derive their names and legends from the high Hindu tradition. They "almost never" have iconographic representations. They are less pure, and thus lower than the "Sanskritic gods." Finally, within their ranks are some of the forms and functions (illness-causing possession) that are proper to some of the members of Bhaktapur's "ghosts and spirits."[74] Harper's village has a residual third group of supernatural beings "devvas, " "free floating marauding spirits . . . malicious and destructive [which] perform no protective functions" (1959, 232). The main contrast with Bhaktapur suggested by Harper's sketch of Tota-

gadde's religion is that there the dangerous deities are much closer to the realm of the immaterial ghosts and spirits than they are in Bhaktapur. The Tantric tradition has facilitated the capturing, embodiment, control, and legitimate civic use of a large segment of supernaturals of this kind in Bhaktapur, and does not place them in an inferior hierarchical relation to the "Sanskritic," that is, the benign Puranic[*] deities.

In Susan Wadley's study (1975) of Karimpur in Uttar Pradesh, the supernatural beings in the "village experience" (that is, in contrast to the unknowable divine principle, the brahman ) were the category of gods, "devas " and a set of spirits and ghosts that, as in Bhaktapur and like Totagadde's "devvas, " were considered outside the class of "gods." The class of devas includes, according to Wadley, both "normally" benevolent and always malevolent deities. The normally benevolent deities (which would include Bhaktapur's dangerous gods) she calls the devata , the remainder "demons." Wadley's main concern is with the differentiations within the class of "normally benevolent devas, " where she suggests (as does Babb, whom we will consider presently) that a central distinction for functional differentiation within the group is the gender and gender relations of the various members. The male devas are referred to as "bhagavan "; the female, as "devi ."[75] The male bhagavan and his concrete manifestations such as Visnu[*] , Siva, and Ganesa[*] , can help people if they are devoted to them. Devotion sets up a social relation, "a relationship based on hierarchical exchange because the gods and men have a commitment to each other" (1975, 117). This set of gods, male gods, can be helpful in gaining "relief from existence and the troubles of existence." These gods can help in getting through the problems of life, but they do not hurt, except presumably by failing to help. These are, thus, similar to Bhaktapur's benign gods, and to Harper's "Sanskritic gods." According to Wadley, the female devatas , the Devi and the component devis , "to a much greater extent than the male gods categorized as bhagavan are potentially malevolent." She cites Babb (1970) and Beck (1969), agreeing that "there is an ever present awareness that female power may become uncontrolled. And when male authority (usually a consort) is absent, the malevolent use of female power is almost assured" (Wadley, 1975, 121). She claims for Karimpur that male deities can always dominate the female deities while female deities have a "potential for malevolent action [that] makes them more suspect than male deities" (ibid., 121). Among the devis there are "some who are almost totally malevolent and act positively only to remedy their own actions" (ibid., 121f.).

Before discussing these observations in relation to Bhaktapur's use of divine gender, we may note Lawrence Babb's extended consideration of the pantheon of various communities in the Chhattisgarh region of Madhya Pradesh. He begins with the familiar distinction about the "philosophical" status of the undifferentiated "world-soul" of Hindu tradition, which he calls the paramatma . This is "an object of contemplation not of worship. Divinity becomes active in the affairs of the universe and men only when it is differentiated into particular divine entities. With this differentiation we move into the world of everyday religious practice. Of all the different kinds of differentiation found within the pantheon, one seems to be particularly stable, that of sex" (Babb 1975, 216). Gender, he argues, sorts two basic qualities of the pantheon. The male "devtas " are "essentially protective and benevolent." The female devis are "the very embodiment of malevolence when unrestrained or unappeased" (ibid.). Babb, starting with suggestions from the Devi Mahatmya , recalls the association of the female goddess as Sakti with "energy" or "force." He notes that in the male-female polarity as conceived in Hindu Tantrism, "the 'female principle' is conceived as the active, dynamic component of reality, while the male principle is regarded as static and passive" (ibid., 220). Taking the angry, destructive, embattled Devi of the Devi Mahatmya in her Kali form as emblematic of that force whose "only discernible emotion is anger—black, implacable and bloodthirsty," he finds female deities in such benign and non-Tantric manifestations as Laksmi problematic, that is, as secondary, and asks, "what is the context in which the Goddess becomes Laksmi?" He suggests that when the male and female deities are related in the ordinary social relation of marriage, with the god dominant—as husbands are—and the Goddess dutifully subordinate, this "imposition of social order" yields deities embodying key values of Indian civilization. He also notes that these social relations allow for "the elaboration of divine attributes in accordance with basic order-producing values—hence the great variety in this sector of the pantheon." In contrast, where the goddess is either alone or dominant, and "if the god appears at all, it is not in the role of husband but of henchman and servant, [then] . . . the pairing as a unit takes on the sinister attributes of the goddess herself. The goddess in this form is not conceived primarily as an exemplar of values and principles, but as the embodiment of an impersonal force—one that can be used, but that may be dangerous to the user, as indeed it endangers the gods themselves until it is contained" (ibid., 225). In a summary he argues, "With-

in the pantheon a very dangerous force is symbolized, but this is a force that seems to undergo a basic transformation into something almost anti-sinister, the loving wife, the source of wealth and progeny, when placed within the context of a restraining social relationship, that of marriage. An appetite for conflict and destruction is thus transformed into the most fundamental of social virtues, that of wifely submission which, on the premises given in Hindu culture, makes the continuation of society possible" (ibid., 226).

These suggestions of Wadley and Babb illuminate a powerful component of the pantheon's semantic force, and are congruent with other meanings of male and female persons and their relations in many societies and as particularly emphasized in Hindu social systems. But these suggestions are not fully applicable, at least in Bhaktapur's version of things. The creative Goddess in her absolute, full form is not malevolent or sinister, and no more uncanny than concepts of Visnu[*] or Siva as creative gods, and certainly no more destructive. She seems to represent a component of a maternal image that is prior to the submissive role of a wife, one worthy of trust and adoration. There are also male forms of considerable malignity, Bhairava, and to a lesser extent the minor dangerous male gods, who are not "henchmen or servants" of a goddess. In some cases the relation to a goddess (as in the case of the Akas Bhairava) helps to make the male dangerous god, less dangerous—in some reversal of the argument. Furthermore, there is at least one female goddess of complete benignity who has in Bhaktapur no present reference to a male controlling and socializing consort, namely, Sarasvati. Furthermore, Siva, when not controlled by social relations, either as a husband or by his friendship to Visnu[*] , is a potentially wild and dangerous being. Finally, the dangerous ghosts and spirits of Bhaktapur are not predominantly female. Granting such qualifications, however, the predominance of the male deities in the domain of moral and social order, on the one hand, and the predominance of independent female ones at the boundaries of that order on the other, is, of course, also characteristic of Bhaktapur. Bhaktapur's imagery and symbolic action treats these independent goddesses as not only dangerous but also as necessary, vital, and protective.

Insofar as Bhaktapur's use of divine gender is less categorical and oppositional than the forms proposed in the studies we have cited, this is congruent with the way Bhaktapur's social system and culture has allowed for the comparatively independent position of women in the family within a Hindu perspective and the resulting modification of

the role and meaning of wife and mother in that perspective. Some of that different emphasis may also be related to the movement of the dangerous female deities from a "non-Brahmanical" social and spatial periphery, as the "folk goddesses" characteristic of Indian villages, to the high-status central position in a socially integrated Tantra (chap. 9), which they have in Bhaktapur.