Chapter Seven

The Symbolic Organization of Space

There is no world without Verona walls, But purgatory, torture, bell itself. Hence "banished" is banish'd from the world, And world's exile is death.

—Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet

Introduction

Frank Kermode wrote of the London portrayed by Joseph Conrad in the Secret Agent that it "is the raw, dark, dirty middle of the world, where there is not structure in space or m time that enables men to know one another, or even to familiarize themselves with inanimate objects" (1983, 48). Bhaktapur is also at the middle of the world, but a polar world to Conrad's structureless turn-of-the-century London. In Bhaktapur space is created and made use of to enable the city's inhabitants to know one another and to know—in fact, to animate—objects.

In the 1850s Ambrose Oldfield ([1880] 1974, vol. I, p. 98) found some confusion in the spatial arrangements of Newar cities:

The streets through the different cities are mostly narrow, crooked and dirty. . .. The streets do not appear to have been laid out on any particular system. Two or three of the principal streets radiate from some of the gateways on the circumference of the city towards the darbar [the royal palace], which is usually situated near its center, and m their course they pass through some of the small squares (or toles ) with which each capital abounds. Other smaller streets connect the different squares and leading thoroughfares together, and these again are intersected by numerous narrow lanes, which ramify about the city in all directions.

But there was also order, (ibid., vol. l, p. 95f. [original parentheses]):

During the time of the Niwar [sic] Rajas each city was surrounded by a high wall, in different parts of which were large gateways, which gener-

ally remained open, but in times of danger or disturbance could be closed and defended. Since the Gorkha conquest of the valley the walls have been allowed to decay. . .. The limits of each city are, however, still strictly marked along the line where the ancient walls stood, and no Hindu but those of good caste are allowed to dwell within its precincts. . .. The number of gateways corresponded exactly with the number of squares (toles ) within the city, each gateway being associated with a particular square, and placed under the municipal control of the same local authorities, who were as much responsible for the repairs and defense of the gateway as they were for the general management of the square. In each city the largest and most important building is the royal palace. . .. It is situated in a central part of the city, and opposite to its principal front there is an open irregular square . . . round which temples of various kinds are clustered together

Oldfield was glimpsing something of the spatial order of the later Malla cities after seventy years of decay. The construction of villages, towns, and cities as symbolic structures is ancient and ubiquitous in South Asia, and Bhaktapur, like the other Malla centers, had borrowed and developed for purposes of such an order a widespread and ancient areal vocabulary of significant spatial forms.

In this chapter we will present what we consider to be the most significant aspects of the organization of space for the organization of the life of Bhaktapur—"significant," that is, for the creation of order through the organization of symbolic form. Obviously, much of the city's urban order is significant in other ways, but such matters as the urban location of various kinds of craftsmen, the channels of transportation and communication in the city, and the spatial residues of (and potential clues for) earlier urban arrangements are of secondary interest for this study.[1]

One of our first approaches to the study of Bhaktapur was a mapping of various aspects of city life—residence areas of thar s, location of temples and shrines, and festival routes—onto maps derived from aerial photographs of the city. During the course of the field research we learned that the urbanologist Niels Gutschow had been doing similar mapping. Gutschow has freely shared with us his maps of Bhaktapur's "ordered space" as he has called it (Gutschow and Kölver 1975), and we have made use of his maps and published writings as a major supplement and extension to our own mappings.

We start, then, with those spatial divisions—areas, lines, and points, that are sources and receptacles for meaning in themselves, that provide meaningful locations for the placement of other symbolic forms and

that set out the stage for what once seemed to be the city's endlessly repeated civic dance.

The City As An Icon of A God

Bhaktapur, as we have noted in our discussion of its history, grew through time in conformance with the limits of early settlements and of topographic constraints. As attempts were made to organize its space as a symbolic resource, it was necessary to deal with hard and resistant forms and forces. The forms that resulted from the interactions of planning and what was—from the viewpoint of an ideal symbolic order—accident or constraint could be coerced into that order in various ways. An existent form might be discovered to have a direct, iconic resemblance to something of transcendent significance; approximate relationships could be abstracted and transformed imaginatively into ideal geometric forms or iconic representations.

The inhabitants of Bhaktapur were thus able to imagine its irregularly ovoid shape as a direct representation of something significant, while at the same time, as we shall see, for other and more important purposes they conceived that shape as a perfect circle. In the eighteenth century Kirkpatrick wrote that Newars described Bhaktapur as resembling "the Dumbroo, or guitar, of Mahadeo" ([1811] 1969, 163). The "dumbroo" was undoubtedly the damaru[*] , the hourglass-shaped drum of Siva. Oldfield, writing of the Nepal Valley m the 1850s, said that Kathmandu, according to Buddhist Newars, was built to resemble the sword of its founder in Buddhist legend, Manjusri, while according to Hindus it resembled the sword of Devi ([1880] 1974, vol. 1, p. 101). Patan, a largely Buddhist city, was said to resemble the wheel of Buddha (vol. I, p. 117), while Bhaktapur (vol. I, p. 131) was said now to represent the conch of Visnu[*] , which is what many present inhabitants still say.

In the case of Bhaktapur (and as far as we know the same is true for the other Newar cities), such iconic images that connect the cities to gods have no ritual or doctrinal significance at all. In contrast to the geometrically regular idealized spaces of the city, they are not used in any way in the actions and elaborations of meanings that constitute the symbolic order of the city. The identification of Bhaktapur's shape with Visnu[*] has no present significance. The city is sometimes thought of as Siva's, sometimes Parvati's, sometimes the Tantric Goddess's, but never Visnu's[*] city.

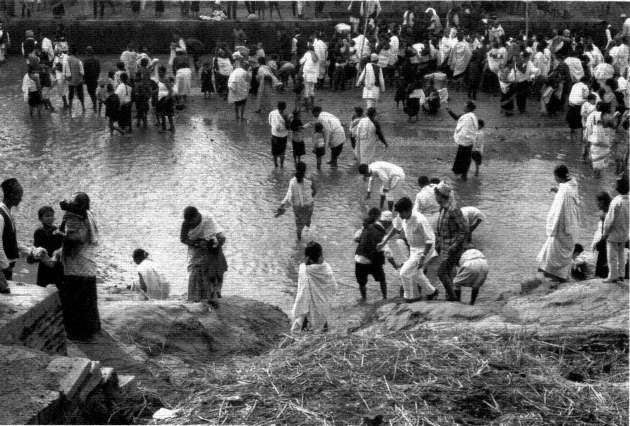

Figure 6.

Ceremonial bathing m the Hanumante River.

A Note on Hill and River

Bhaktapur, like very many cities, makes use of a hill—on which it is built—and a bordering river (see fig. 6), but characteristically elaborates and adds to their elementary "practical" significance—the hill as potential citadel, or as a residential center for the exploitation of the surrounding arable farmland, the river as a source of water (but not, in the Kathmandu Valley, for navigation). The hill, with its higher-status temples, palaces, and residential areas located toward its crest, adds to the more significant orientation of central-peripheral (discussed below) an additional dimension of higher-lower. Bhaktapur is situated in accordance with the traditional ideals of South Asian town planning on the right bank of its river (Dut [1925] 1977, 24), the Hanumante. As is the case for all Newar royal cities and for those secondary Newar towns situated on rivers, the direction of the flow of the river is one basis for the discrimination of an important division of the city or town into two halves, an upper half (upstream), and a lower half (downstream). The river, a locus for dying, cremation, and purification, is outside the traditional boundaries of the city and takes much of its meaning (which it shares with the ideal symbolic Indian river, the Ganges) from its transitional position at a boundary to another world and its flow toward still another, whose orders are other than that of the city.

The Idealization of Space: Bhaktapur As A Yantra

In map 1, a schematic illustration of the location of the shrines of the nine guardian goddesses of Bhaktapur (those who protect its boundaries and what we shall refer to as its "mandalic[*] sections"), one of the city's Rajopadhyaya Brahmans represented the goddesses' locations as points in a symmetrical diagrammatic city. The drawing is labeled "Yantrakara khwapa dey'"—"Khwapa dey'," "the city of Bhaktapur," portrayed as a "yantra ." The diagram shows Bhaktapur's boundary as a circle, a mandala[*] , a pervasive South Asian representation of a boundary and its contained area within which "ritual" power and order is held and concentrated.[2] The circumference of the mandala[*] separates two very different worlds, an inside order and an outside order, and suggests the possibility of various kinds of relations and transactions between them. Within the mandala[*] in the drawing is the yantra , "a mystical diagram believed to possess magical or occult powers" (Stutley

Map 1.

Idealized symbolic form. A drawing by a Bhaktapur Brahman of Bhak-

tapur as a yantra with the nine Mandalic[*] Goddesses represented at the eight

compass points and at the center. The actual spatial location of the nine god-

desses is given in map 2.

and Stutley 1977, 347), typical of Bhaktapur's imagery (chap. 9), here made up of two overlapping triangles, representing the relation of opposites, of male and female principles, unified in a point at the center of the diagram. At that central point is written the name of one of Bhaktapur's nine protective goddesses, Tripurasundari. Toward the periphery, at the circular boundary are the names of the eight other protective goddesses. They are exactly arranged at the eight points of the compass, with the top of the diagram conceived as representing the north.

These goddesses exist in the actual space of Bhaktapur (map 2), but

Map 2.

The spatial positions of the pithas of the nine Mandalic[*] Goddesses. These are the actual spatial locations of the idealized

points of the symbolic yantra and mandala[*] in map 1. The numbers designate the deities in the sequence in which they are worshiped

when treated as a united collection of deities: (1) Brahmani, (2) Mahesvari, (3) Kumari, (4)Vaisnavi[*] , (5) Varahi, (6) Indrani[*] , (7)

Mahakaili, (8) Mahalaksmi[*] , and (9) Tripurasundari. The dense band of dots in this map and the following maps indicating the extent

of the city represents the edge of the presently built-up area of the city, the "physical city," and does not necessarily correspond to the

city's symbolic boundaries. Map courtesy of Niels Gutschow.

the central shrine and the ones at the boundaries are only approximately at the eight points of the compass and at the city center (cf. Auer and Gutschow n.d., 22). One of them is even further displaced from where it is "supposed" to be, being physically within the symbolic boundary of the city instead of at or beyond its outer border as are the other boundary protecting shrines. As Mary Slusser speculates of that shrine, that of Mahalaksmi[*] , in the course of the construction of a boundary-marking city wall "the sanctity of the [preexisting] old shrine forbade moving it to an optimal location outside the wall; engineering or other considerations dictated the latter's course, thus enclosing the . . . [shrine] within the city walls" (1982, vol. I, p. 346). In accordance with the struggle and the dialogue between the given on the one hand and the ideal symbolic form on the other, Bhaktapur had to construct and imagine a yantra and its encompassing mandala[*] as best it could.

This imaginative process takes features of real space, many of them constructed under the impetus of that imagination, and perfects them—the city becomes a bounded circle instead of a flattened irregular oval. Simultaneously in a dialogue of imaginative and actual space city halves, "mandalic sections"—various axes and centers—have been constructed. Those imaginatively perfected forms exist in real space like a geometric image reflected in a distorting mirror. But people have no trouble finding their ways about in one or the other kind of space or, for that matter, in both at the same time.

The City Boundaries and the Bordering Outside

Bhaktapur, like the other Newar royal cities, was, as we have noted in chapter 3, once more or less surrounded by a wall that was pierced by gates. The wall had a defensive use, as descriptions of Bhaktapur's resistance to the siege of the Gorkhalis in 1769 vividly attested. However, the defensive uses of city walls, Paul Wheatley has argued, "in both Nuclear America and Asia [he is writing of early traditional cities] . . . were often much less important than in the West European city. In fact, not infrequently those constructions which the modern mind is predisposed to interpret as fortifications, and which may indeed have been pressed into service as such during emergencies, were in reality symbolic representations of the bounds of the cosmos" (1971, 372). Bhaktapur's wall (whatever other functions it had) and the boundaries it once marked were of enormous "symbolic" importance, as those

boundaries still are. Those boundaries may not represent the boundaries of the cosmos, for there is some sort of world beyond them, but they represent the boundaries of its central order, the order that is congenial to human beings and to what we will call (chap. 8) the "ordinary deities."

The various spatial features of importance of the city's symbolic organization, which we will be concerned with in the remainder of this chapter, are anchored in real city space by physical features—particular stones, shrines, temples, roads, and pathways. In the course of the "symbolic enactments" that take place in relation to these markers, significant points, boundaries, axes, and areas are clearly designated. In most cases these significant spatial features can be precisely mapped. When the city walls and their gates were still intact, the boundary of the city as a whole was, of course, clear. At that time it was, in fact, the only one of the spatial boundaries we are concerned with that was entirely represented in a physical, material form. Now in Bhaktapur the wall has disappeared except for a few gateways placed at the old ceremonial entrances into the city, and the problem for the people of Bhaktapur in knowing exactly where the city's boundaries are at all points is greater, often considerably greater, than it is for locating the boundaries of smaller units. Kathmandu still has a processional route annually followed by members of families bereaved during the previous year that follows and thus traces and retains in civic memory the ancient and now leveled walls of that city (Slusser 1982, vol. 1, 93). Bhaktapur does not have any such ceremonial tracing of its boundaries (although there is something like it in orderly sequential visits to the shrines of the boundary-making goddesses during the autumnal harvest festival, Mohani; see chap. 15), but rather marks and infers the boundary by the contrast of certain events and conditions held to take place properly outside of it but not inside. The city boundary is a dimensionless line producing an instant transformation between the inside of the city and the outside. The symbolic emphasis is on the outside of this line, what happens to citizens at home in Bhaktapur when they cross this line, and what kind of a contrasting world they find there. The inside and the outside help define each other. Not only is the emphasis on the outside of the line in its contrasts to the inside (and not on the line itself), but the emphasis is for the most part on a special aspect of the outside, the immediate outside, the bordering outside. The distant outside—where in Malla days one would eventually reach the other Newar cities, and beyond them Lhasa and India—is something else.

We will note some of the things and events that exist or take place just beyond the boundaries. This, like much of this chapter, will serve to introduce subjects dealt with in more detail and in different contexts later in the book.

City Boundaries: The Boundary-Protecting Goddesses

As we noted in the discussion of the drawing (map 1) of Bhaktapur as an ideal mandala[*] or yantra , there are the shrines of eight goddesses placed at the eight points of the compass at the boundary, and a ninth at the center.[3] The nine goddesses as a set are related to the internal division of the city's space into nine "mandalic[*] areas," and we will discuss this division below. The eight external goddesses preside each over her own area of the city, but together they protect the boundary itself. As a group of eight, they are the Astamatrkas[*] , the "Eight Mothers," whose positions, marked by open, aniconic shrines called pitha s, are conceived to be (although as we have noted, one of them is, "in fact," not) not only exactly at the eight points of the compass (which again they are not "in fact") but just outside the boundary of the city (see map 2). The Astamatrkas[*] are important members of a special class of deities, the "dangerous" deities, and represent a major component of that class, the manifestations of the "dangerous goddess," "the Goddess," Devi. We will return to Devi as a deity in chapter 8, in relation to the specific worship of the dangerous deities and Tantra (chap. 9), and again in that portion of the annual calendrical cycle devoted to her (chap. 15). The group of dangerous deities (who are ritually specified in that they—in contrast to the "benign deities"—receive blood sacrifices and offerings of alcoholic spirits) represent dangerous and at the same time vital forces that lie beyond the city's inner moral organization and also represent the defenses against those dangerous forces through a transformation in which those forces have been tenuously captured and controlled and placed at the service of the city. These particular goddesses ring the entire city and protect it from specific kinds of danger, such as earthquake, disease, and invasion. It is proper for them to be placed to the exterior of a boundary because they are the kinds of deities who are, as we will see, "semantically" proper for their particular job. Their position at the city's boundaries is not only a defense but a reminder of the kind of a world to be encountered there and of the contrast of that world with the interior where—within small protective perimeters of

various kinds also defended by the dangerous deities—a quieter moral order can proceed under the tutelage of other kinds of deities.

As is the case with most of the significant symbolic markers of Bhaktapur's mesocosm, an encounter with the Eight Mothers and the boundary they represent, protect, and characterize is ineluctably brought about in the course of certain necessary symbolic enactments. The protective goddess of a person's particular residential area of the city must be worshiped during the course of certain major rites of passage by the male members of the extended patrilineal family unit, the phuki . Almost all of Bhaktapur's people also visit the boundary shrines (and their central focus), over the course of nine days of the major autumnal harvest festival, Mohani (chap. 15). People visit each one on its particular designated day, proceeding in the course of the nine days in the auspicious clockwise direction from one shrine to the next, finally, in effect, circumambulating the city's borders.[4]

City Boundaries: The External Seat of the Lineage God, The Digu God

The people of Bhaktapur must cross to the outside of the city's boundaries (see map 3) to worship their phuki 's lineage deity, represented usually by a "natural" stone and worshiped through the rituals proper to dangerous deities (chaps. 8 and 9). This god is the Digu God (or sometimes and popularly, the Dugu God), the lineage deity of a phuki . The Digu God worship is for the highest thar s, (Pa[n]cthariya and above)—that is, those who have upper-class Tantric practices—only one of two major components of lineage god worship (chap. 9), but for the middle-level and lower-level thar s it is the only form. The location of shrines for the worship of lineage gods on the outside of a settlement or village is also the practice of Nepalese Chetri communities (K. B. Bista 1972, 66) and has been described in other Newar communities (e.g., Toffin 1977, 31). Informants in Bhaktapur cannot explain why the shrines of the Digu God are outside of the city; explanatory stories are vague, and it is unclear to what possible historical reality they might refer. One story is that in the days of the Malla kings all families of Newars went to the same town (Hadigaon)[5] for their lineage god worship, with each lineage presumably having its own shrine there. But, the story goes, as this was too far away the shrines were moved to the outskirts of each of the Valley cities. Some others say that the place

Map 3.

The symbolic boundaries of the city. The external placement of the Digu lineage gods. The physical city is represented as a

bounded shaded area. Each peripheral dot represents the placement of the external lineage deity of a particular phuki or of a group of

split phukis. Map courtesy of Niels Gutschow.

where the shrines are located is the place where the original founders of each family lineage entered the city. This comment on the exterior position of the Digu God shrines suggests an actual or fantasized connection of their locations in the past to the historical origins of the city's ancient patrilineages.[6] If this connection (if it ever really existed) is now mostly lost, the Digu Gods must nevertheless be worshiped just to the outside of the city's boundaries, and it is the kind of worship and they are the kinds of gods that point outward beyond the organized interior life of the city.

City Boundaries: Cremation, Dying, And Purification

The river is considered to he outside of the city's boundaries to the south, as are the ghat[*] s (Bhaktapur Newari, ga :) or steps leading down to the river on its city side. At the river clothes are washed and people bathe as a phase of major purification procedures (chap. 11). People approaching death are sometimes brought to the river ghat[*] s so that their feet and legs may be immersed in the river at the actual moment of death (app. 6). The city's three cremation grounds (Newari dip , from Sanskrit dipa , burning, blazing) are also outside the city, as they are in all South Asian Hindu communities. Two of the major cremation grounds are beyond the river and, as they should be ideally, to the south of the city. These two cremation grounds (Khware Dip and Mu ["main"] Dip) are each associated with one of the ghat[*] s on the city side of the river, and are connected to them by bridges spanning the river. There is a third major dip , Bramhayani (Sanskrit Brahmani),[7] to the east of the city, named after the protective boundary goddess of the eastern pole of the city.

Although we are concerned here with city boundaries and inside/ outside contrasts and relations, it is convenient at this point to introduce some other aspects of the cremation grounds in their relation to city space and to its status system. The three dip s are for the "clean" thar s, the "unclean" ones use various fields outside the city (although on the city side of the river) away from the three main dip s. Various Newar chronicles suggest that the cremation areas of most of the significant macrostatus groups were, or at least were held ideally to be, separated. Thus, according to Hasrat's chronicle, Jayasthiti Malla "distinguished and classified thirty-six tribes according to their trades and professions . . . [and] constituted for each of the thirty-six a separate masan [cremation ground] or place for burning their dead" (Hasrat

1970, 55ff.). There are now traditional places within the grounds for some thar s, but as a whole the cremation grounds are related to areas of the city, rather than to social status. People who have been brought to die at Hanuman ga : are cremated at the Khware Dip. Those who had been brought to die at Cupi(n) ga : are cremated at the Mu Dip. It is a matter of family custom and choice which ga : they are brought to. Most people die at home, within the city, and these people are usually cremated at Brahmani Dip if they live in the upper half of the city, and Mu Dip if they live in the lower hall

Gutschow and Kölver (1975) called attention to the fact that funeral processions to the dip s were determined by residence in a particular twa: (a village-like division of the city; see below). "Now there are exact prescriptions regulating not only who has to use which [cremation ground], but also the way a corpse has to be borne to his proper place of burning. The decisive feature in this is geographical. The body of a man who belonged to a particular ward [twa: ] has to be carried along the way prescribed to all the members of his ward" (Gutschow and Kölver 1975, 27). These differentiated routes, based on twa: residency, recall Oldfieid's statement, previously quoted, that the number of gateways in the old city walls exactly corresponded to the number of toles (twa: s) in the city, and that the maintenance of the gates was the responsibility of the local twa: authorities (Oldfield [1880] 1974, vol. I, p. 95f.). Because of the mixed collection of thar s in many twa: s, this arrangement, as Gutschow and Kölver point out, tends to neutralize the distinctions of caste (1975, 27).

This "communitas, " represented by a collapse of status distinctions in funeral procession and place of cremation, is typical of many activities that are outside and beyond the ordinary civic structuring of Bhaktapur; for example carnival and Tantric rituals. In all of these, however, there is always a residue that is excluded from the egalitarian community, in this case the lowest thar s, who are refused even the common cremation grounds.[8]

City Boundaries: The Untouchables' Proper Place

In all traditional South Asian cities the lowest segment of the social hierarchy had to live outside the city, and was thus designated as being in opposition to the pure inhabitants of the inside of the city.[9] The ancient classical Indian treatise on applied politics, the Arthasastra of Kautila[*] , states that "heretics and candalas shall live beyond the burial

grounds" (quoted in Dutt [1925, p. 151]), which themselves were to be outside the city.

Various chronicles or vamsavali presenting Jayasthiti Malla's formalization of Bhaktapur's religious, social, and economic organization, note that Poriya (Bh. Po[n] or Pore), had to live outside the city (see map 4), and could not enter the city after sundown (Hodgson manuscripts, n.d, vol. 11, p. 114; Basnet [1878] 1981). Oldfield, in the sequel to some remarks that we have already quoted, wrote of the Newar old "capital cities" (in which he included the large secondary town of Kirtipur) that, "The limits of each city are . . . still strictly marked along the line where the ancient walls stood, and no Hindus but those of good caste are allowed to dwell within its precincts. This rule does not apply to Mussalmen, several of whom reside within the city of Kathmandu, but it is strictly enforced against Hindu outcasts, such as sweepers, butchers, executioners, etc., all of whom are obliged to live in the suburbs of the city" ([1880] 1974, vol. I, p. 95).

The sweepers and executioners are the Po(n)s, whose symbolic functions are, as we will see, of great persisting importance in Bhaktapur. The inclusion in this quotation of "butchers," the Nae, introduces a problem, and almost surely an error into the literature on thar residence patterns.[10] Nae at present live within the boundaries of the city, although they are located at its periphery, at the farthest from its high-status center (map 9, below). There are other low thar s, some of which are even lower and more impure than the Nae who live within the city, and to all evidence always have, for example, the Jugi (map 10, below).

The question of the position of the Nae in relation to Bhaktapur's boundaries is connected with another question, one concerning the position of the city's main city-wide processional route, the pradaksinapatha[*] . In ideal ancient Indian tradition the pradaksinapatha[*] surrounded the village or city (Dutt 1925, 33), and Mary Slusser has argued that this was the case in Kathmandu (1982, vol. 1, p. 93). The Bhaktapur pradaksinapatha[*] (map 12, below) moves within the city as a flattened meandering oval, roughly paralleling the city's boundary, running through and thus tying together all except one outlying twa: (below) as well as the upper and lower cities. Bhaktapur's internal pradaksinapatha[*] position within the city also is found in the Newar town of Panauti. Barré et al. argue that in the town of Panauti the processional route acts as a "boundary of purity," as the butchers and sweepers live in its exterior (1981, 40f.). Such a tempting distinction does not work for the distribution of thar s in Bhaktapur (and even in

Map 4.

Space, status, and the symbolic boundaries of the city. The settlement of the Po(n) untouchables at the southern edge of the

city. The settlement is considered to be lust beyond the symbolic boundaries of the city. Map courtesy of Niels Gutschow.

the cited account of Panauti there are admitted exceptions, like the dwellings of the very low Jugis within the central area). As we have noted, the interior position of the pradaksinapatha[*] in Bhaktapur, and the fact that both the sweepers and the butchers live peripheral to it, led Gutschow and Kö1ver (1975, p. 21) to speculate that it follows the external boundary of some earlier city of Bhaktapur, but there is no apparent collaboration for this in other historical, archaeological, or persisting social forms.

It is unequivocally the Po(n)s, the sweepers, however, who have the special symbolic function of being intimately joined to the city to represent its most salient and necessary outsiders—they are the ones who must live just beyond the boundaries, and who in their conditions of life and in their powerful embedded meanings represent the transforming significance of that boundary to those privileged to live within it.

On Boundaries

The city walls and most of its gateways are long gone, but everyone in Bhaktapur knows that they exist, that the city is a clearly bounded entity, surrounded by an outside of contrasting nature, and they know approximately where the boundaries must be. They cannot ignore the boundary as they must cross it to the outside for worship of lineage gods, for worship of the "Eight Mothers," often to die and always to cremate others and be cremated themselves, and they must be sure that the untouchables, with whom they are deeply concerned, are fixed in their right place. The outside with which they are necessarily engaged is not everything outside of Bhaktapur, but a highly symbolized zone of encirclement. The far outside, which may be contrasted with this encircling, bordering near outside, includes areas of very mixed meaning—other Newar cities, pilgrimage sites, non-Hindu countries, and so on. But the near outside represents the anticity. The relation of bordering outside to inside characterizes not only the city as a whole but also the relations of many of its nested units to their particular outsides, and is reflected in many ways, in kinds of gods, kinds of worship, and the interplay between power and morality, kings and Brahmans. We will be concerned with these relations throughout the following chapters.

The relations of outside and inside are not a simple opposition. The outside has its special values—it has something to do with fertility and useful power as well as danger. As the kinds of deities who character the two realms suggest (chap. 8), outside and inside have different logics,

different relations to moral order. But all this is complementary. The major supernatural creatures at the outside are gods themselves, not antigods like Satan. The ordinary deities, like the ordinary people, need those outside gods, even if they are not comfortable with them.

In the symbolic representation and symbolic enactments concerning the city boundaries, it is the bordering outside and its nature that is emphasized. That outside is of such a nature that after a brief, lively, and instructive encounter with it, people are moved to reenter ordinary civic space with some relief. From the point of view of its impact on citizens for the purposes of social order the smbolization of the outside tends to push people back within the civic boundary.[11]

When the public space of the city as a whole is the focus of attention, as it is generally in this book, the external outside beyond the encircling borders is only one way out of the public city. Insofar as the behavior of an individual, a family, or whatever unit is out of the general public sight and of the direct influence of the city system, they are, from the point of view of that system also "outside," and thus households, thar s, guthi s, and so on, as well as the private "inside" part of a person's thoughts are outside the public moral world of the urban mesocosm. The inside of the city as a public moral civic space can be escaped in various directions, and the outside beyond the civic boundaries often joins in meaning with the small private realms hidden within the city.

Bhaktapur As A Mandala[*] : The Nine Mandalic[*] Section

When Bhaktapur is conceived of as a yantra placed within a bounding mandala[*] , the segmentation of its interior space is now at issue. Now the Eight Mothers, the Astamatrkas[*] , not only protect the external boundaries of the city at the eight points of the compass but also individually protect the particular octant of the city lying in their general direction and, thus, under their influence. The protective goddesses for the octants are Brahmani to the east; Mahesvari to the southeast, Kumari to the south; Bhadrakali[*] (sometimes represented as another goddess, Vaisnavi[*] ) to the southwest; Varahi to the west; Indrani[*] to the northwest, Mahakali to the north, and Mahalaksmi[*] to the northeast (map 2).[12]

Each goddess has a "god-house" in her city segment, where her portable images is kept (map 2). During one of the year's major festiv-

als, Biska: (chap. 14), the images are brought from the interior of the city each to its boundary shrine, and the internal image and the external aniconic shrine are united. The emphasis has shifted from the protection of the boundary to an internal radiation of the power of the goddesses. That power not only plays over the eight peripheral octants into which the city is divided but is also focused and concentrated at the center of the mandala[*] , in the shrine or pitha of still another, a ninth goddess, Tripurasundari. This Goddess protects the city's central area in a circle around her. The city is thus divided into nine areas—a circular center and eight peripheral sectors. We may call these nine segments "mandalic[*] sections." These nine divisions are also conceived by Bhaktapur theorists as a lotus, with a center and eight petals, a very common Hindu form, corresponding to one classical Indian ideal village form (Dutt 1925, 29).

Each mandalic[*] segment is designated by its protective goddess plus any term for area or place, for example, Mahakali ya ilaka , signifying the territory under Mahakali's protection. People are thought to belong to the mandalic[*] section in which their father's patriline had been "established." That is, if they move to another part of the city, their protective goddess and that of their descendants born in the new section is the goddess of the mandalic[*] section where they had previously, and presumably "always," lived. After marriage, a wife is considered to belong to her husband's mandalic[*] section and ordinarily prays to that section's goddess, although she is still related to her natal goddess in those rituals of her natal family in which she continues to be involved.

The mandalic[*] segment that one belongs to determines which specific Astamatrka[*] shrine or pitha one must visit during certain important rituals, particularly during those associated with the samskara s, or rites of passage. During the annual harvest festival, Mohani, in which the whole city is supposed to visit each of the nine pitha s in daily turn over nine days, the people in each goddess's section are responsible for decorating her pitha and god-house on her particular day. In some Tantric initiations for higher-level thar s, the particular mantra used and the tutelary god assigned to the person being initiated is based on his particular mandalic[*] segment (chap. 9).

The central goddess Tripurasundari is, as we will discuss in the next chapter, the proper kind of dangerous goddess to be at the center of the mandala[*] 's power. She is a "full" goddess, and the peripheral forms are partial and more specialized. She is represented at the center of the lotus or mandala[*] where power is concentrated and at its maximum, and

sometimes to similar effect as a point sending out rays of power in each of the eight directions of the compass to each of the eight pitha s at the boundaries. In contradistinction to the way the city uses other "full," maximally powerful forms of the Goddess (such as Taleju and Bhagavati), however, and in spite of this schematic superiority to the eight peripheral goddesses, there is no special emphasis of any kind now on Tripurasundari's central shrine, nor on the central mandalic[*] section that she protects. In action and interpretation, Tripurasundari (in her function as a central pitha goddess) is the exact equal of the other Mandalic[*] Goddesses. Some local diagrams of Bhaktapur as a mandala[*] have the Newari word for king, juju , written next to Tripurasundari. Some Bhaktapur informants speculate that the shrine's centrality may have reflected a possible ancient relationship to the twelfth-century royal palace, Tripura, which they believe to have been near the present pitha , and they assume that the Tripurasundari pitha may have then been the special shrine for the king and his court (cf. Slusser, 1982, vol. I, p. 345ff.). In the seventeenth century the court and its associated temple of Taleju was moved to its present western site.[13] Tripurasundari lost her central political importance. This suggests that she remains as a striking example of a once powerful symbolic statement that later lost much of its social, ritual, and personal meaning in a transformed Bhaktapur, where now the curious thing about her is the absence of what she once was.

City Halves: Ritually Organized Antagonism

The bounded units we are considering are in part defined by their contrasts with their adjoining units, in a contrast where that adjoining unit is often an encompassing one (the city and its environment, the house in its twa: or neighborhood), although it may be, as in the case of adjoining mandalic[*] sements, a contrast of units at the same level. For the most part any antagonistic implications of these contrasts are mitigated by a pervasive Hindu metaphorical move, an emphasis on the organic unity and interdependence of the contrasting units to form some higher vital synthesis, the various units being metaphorically related (like the ancient four Varnas[*] ) as being like the parts or organs of the body. Neither the high head nor the lowly feet, although different and of different status, can live without the other; they are joined into something superior on which they are dependent, on which their very lives depend.

However, there is one symbolically marked division of the city, its halves, where the major emphasis is precisely on conflict, albeit a conflict periodically and tenuously resolved in symbolic acts. This emphasis on the antagonism of the halves seems to deflect other more dangerous antagonisms within and among smaller city units.

Bhaktapur is divided into halves, an upper half (cwe , or up, or tha:ne , above, upward) and a lower half (kwe , down, or kwane , below, downward) (map 5). As D. R. Regmi wrote, the division may have been a general feature of all Newar settlements and "obtained in every case whether it was a town or townlet" (1965-1966, part I, p. 554). The division has been described for Kathmandu (Regmi 1965-1966, part I, p. 554; Slusser 1982, 90-91), for the Newar village of Theco (Toffin 1984, 186ff.), and for the large Newar town of Panauti (Barré et al. 1981, 46). As Barré writes, the division into upper and lower city is "a characteristic common to Newar settlements whether urban or rural."

It is often stated that the upper and lower segments are designated in relation to the flow of neighboring rivers (e.g., Toffin 1984, 200) with upstream locating the direction of cwe , downstream of kwe . Inhabitants of Bhaktapur attempt various explanations of the designations "up" and "down." Bhaktapur's "upper half" for some is upper because it is more northerly, for others because it is in the direction of the high Himalayas, in contrast to the progressively lower, that is, less elevated southern regions. This north-south interpretation of "upper" and "lower" is reflected in a use of "kwane " among Valley Newars, at least until the last generation, to indicate India. Other speculations are that the upper half, cwe , was the earliest part of the city settled (as was, in fact, true for Bhaktapur), followed by a later settlement, kwe . (Here the usage corresponds to the temporal terminology for ancestors [cwe , up] and descendants [kwe , down].) Still other people give the upstream/ downstream, explanation. It is possible, at least, that the upper/lower contrast is basic to the social organization of all Newar settlements, and that a variety of relations to physical space and settlement history can be used to choose between the terms of the distinction or to justify them. Bhaktapur's upper and lower cities are divided by a line perpendicular to the long (the southwest-northeast) axis of the city, and thus consist of a somewhat northerly eastern portion, and a somewhat southerly western portion, which are respectively upstream and downstream in respect to the Hanumante River (see maps S and 11 [below]).[14] As D. R. Regmi writes, in contrast to Kathmandu, where the royal palace was at the central position in the city and provided a locus

for the division of the city into upper and lower halves, "the [Bhaktapur] Royal palace was situated at the western extremity of the town and the center dividing the city was the courtyard surrounded by the Nyatapola [Natapwa(n)la] and Bhairava temples" (1965-1966, part II, p. 554). This square, Ta:marhi (also pronounced or written Tamari, Taumadhi[*] , Taumarhi, etc.), is conceived as at the center of the city division in one of its most important ritual expressions, the struggle between members of the two halves of the city to pull a huge chariot positioned there into their respective halves of the city during the Biska: festival at the time of the solar New Year, a struggle sometimes marked with considerable violence (chap. 14). At that time the square is considered the neutral center between the halves, but ordinarily it is considered as belonging to the lower city and the people living around it consider themselves at all times to be members of the lower city. Guts-chow and Kö1ver note that the Ta:marhi Square has a "profuse endowment" of religious buildings and is the site of the highest temple (and building) in Bhaktapur, the Natapwa(n)la temple (fig. 10). They argue that this profusion of monuments may be understood as a device for unifying the town by installing a mediating center and affirming the unity of the city (1975, 50). Although the old Malla Royal Palace, the square in front of it, and the adjacent residential area of the Rajopadhyaya Brahmans (maps 5 and 6) is, like Ta:marhi, in the lower half of the city, during the struggles of the city halves in the course of the Biska: festival that area is also said to belong to neither the upper nor lower city. It is often said that the Malla kings encouraged the division and conflict between the two city halves, which they transcended, to strengthen their power and divide any potential opposition. Thus, if Ta:marhi Square acts as a neutral ritual center between the upper and lower cities, the royal central area, in spite of its peripheral western positions, is in its own way also a neutral point.

In recent years conflict between members of city halves has also sometimes broken out at certain other festivals, but these rare and recent struggles are considered to be accidental and unintended disorder and breakdown. The peculiarity of the Biska: festival is that it includes as one element in its complex dramatic structure a prolonged struggle between the two city halves, a struggle that eventually comes to a resolution.

Ritualized struggles (that is, struggles induced and regulated by traditional forms and conventions—which does not prevent them from having, sometimes, serious consequences) between socially organized

Map 5.

The struggle of the upper and lower halves of the city and its resolution. The routes into the upper and lower halves of the city

contested in the struggle to pull the Bhairava chariot during the Biska: festival (chap. 14). The arrows in the upper and lower segment

of the city show the ideal termini of the chariot and the acceptable shorter termini if there is not time to reach the ideal ones. The

southerly arrow shows the chariot's ultimate "central" route into Yasi(n) Field, where it must witness the raising of the Yasi(n) God to

mark the solar New Year. Map courtesy of Niels Gutschow.

Map 6.

Space and status. Households of Rajopadhyaya Brahmans. The greatest concentration is just south of the Taleju temple and

the Royal Palace and represents a center of the city. Map courtesy of Niels Gutschow.

halves or moieties of a community—are reported for traditional South Asian communities as they are elsewhere in the world. Dubois, for example, remarked on the struggles between the "left-handed" and the "right-handed" factions in the Deccan and Madras areas in the early nineteenth century, factions to which "most castes" belong, which "proved a perpetual source of riots, and the cause of endless animosity amongst the natives" (1968, 24f.). He also remarks on something that has a bearing on the conflict in Bhaktapur, that "in the disputes and conflicts which so often take place between the two factions it is always the Pariahs [the untouchables] who make the most disturbance and do the most damage" (ibid., 25). And, he states, also in an echo of Malla Bhaktapur, "the Brahmans, [and] Rajahs. . .are content to remain neutral, and take no part in these quarrels. They are often chosen as arbiters in the differences which the two factions have to settle between themselves" (ibid., 25).

Hamilton cites a report for the turn of the nineteenth century by a Colonel Crawford, which describes a "vile custom" of the Newars of Kathmandu, who had previously been described by Hamilton as being an otherwise peaceable people ([1819] 1971, 43f.):

About the end of May, and beginning of June, for fifteen days, a skirmish takes place between the young men and boys of the north and south ends of the city. During the first fourteen days it is chiefly confined to the boys or lads; but on the evening of the fifteenth day it becomes more serious. . . . [A fight then takes place which] begins about an hour before sunset, and continues until darkness separates the combatants. In the one which we saw, four people were carried off much wounded, and almost every other year one or two men are killed: yet the combat is not instigated by hatred, nor do the accidents that happen occasion any rancor. Formerly, however, a most cruel practice existed. If any unfortunate fellow was taken prisoner, he was immediately dragged to the top of a particular eminence in the rear of his conquerors, who put him to death with buffalo bones. . . . The prisoners are now kept until the end of the combat, are carried home in triumph by the victors, and confined until morning, when they are liberated.

There has been speculation, deriving from a further remark of Hamilton's (1971, 44) that some people alleged that the Kathmandu battle reflected some old division of the city into two towns under two Rajas and first arose as skirmishing among their respective followers, and that the division in Kathmandu, at least, and perhaps in other Newar towns may have reflected some earlier antagonistic political segments later merged into the towns (Slusser 1982, vol. 1, p. 91; Toffin

1984, 201f.). Yet, the ubiquitousness, persistence, and evident usefulness of the division in Newar communities would suggest that such historical explanations would only apply to some towns, and would only help explain the location of the halves, not their existence and persistence.

In some ways the upper and lower cities in Bhaktapur are two different cities. it is said that people usually marry within their own half of the city. In many contexts, they identify themselves as belonging to one or another hall Significantly, when there are crimes or disturbances in the city whose perpetrators are unknown, it is common to hear remarks by people from the lower city that it must have been someone from the upper city, and vice versa. Although the lower city has the main concentration of Brahmans and high-status Chathariya, and the upper city the main concentration of upper-status Buddhists, for the most part each city half has a full representation of important social and occupational units.

For ordinary considerations of residence (where we can ignore the mandalic[*] sections), the city halves are the next largest segment after the village-like twa: s (see discussion below). It is our impression that the antagonism directed toward the relatively distant other city half, out of and away from one's own closely interdependent area, deflects intra-twa: resentments that would affect relations between families, phuki s, thar s, and macrostatus levels—relations whose disturbance would be disruptive to the basic integration of the social system—to the other city within the city where they can be expressed in comparatively very much less disruptive and dangerous ways. Members of lower thar s who are annoyed and resentful of their treatment by higher groups find it easier, like the pariahs in the quotation from Dubois, to help precipitate a fight against members of a disliked group in the other half of the city, where it would be interpreted as a spatial struggle rather than one within the social system.

Status and Space: Concentric Circles

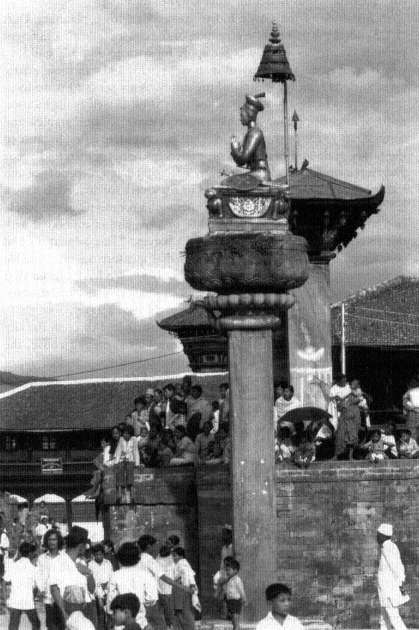

It is convenient to introduce in this chapter aspects of the urban spatial distribution of some of the thar s and status levels (see fig. 7). Only a portion of this distribution is directly related to the urban symbolic order in our present sense, the greatest part being closely related to aspects of economic function, to communication and transportation, to

Figure 7.

The Royal center. Statue of King Bhupatindra[*] Malla in Laeku Square.

relations of power, to the special needs of the old court, and to historical "accident," thus reflecting other kinds of meaning.

In his study of the classic Indian treatises on town planning, Dutt (1925) notes the planned "segregation of the classes following different pursuits. . . . Every ward was set apart for a caste or trade guild . . . which enjoyed an autonomy of its own" (1923, 147). In some classic texts, such as Kautilya's[*] , detailed prescriptions are set out for the location of many occupational specialites and castes, as well as the location of royal kitchens, elephant stables, water reservoirs, camel stables, and so on (Dutt 1925, 149f.).[15] But, as Dutt points out, in cities, because of the larger scale and because "corporate life connotes manifold needs and responsibilities and consequently necessitates interdependence and inter-communication," various areas or sites were subdivided to have a representation of occupations, and became "a prototype of the whole city on a smaller scale." And, he adds, in a suggestion connected with our interpretation (above) of the city's halves, "This admixture and congregation of classes came as a remedial measure against possible accentuation of class differences" (1925, 148). We have argued that the city halves are such city prototypes in Bhaktapur, as are, to some degree, the twa: s, which we will discuss in the next section.

Although many of the thars are widely distributed through the city according to the kinds of functional principles suggested above, the arrangement of certain symbolically important groups has the kind of idealized mythic arrangement characteristic of marked symbolic space. When these thars are considered—the king and his associates, Brahmans, farmers as a group, butchers, and untouchables—a geometrically idealized Bhaktapur is organized in a series of concentric circles from a center out, and at the same time, as it is built on a hill, from top down. At the center of high status is the palace of the Malla kings, and the temple of the Malla kings' lineage deity, the supreme political goddess of Bhaktapur, Taleju. Just to the south of the palace, but also centrally located is a major concentration of Rajopadhyaya Brahmans (map 6), including those families who were the king's and his goddess' special priests. Intermingled in central residence with the Brahmans, but filling a still larger segment of the city are the Chathar and Pa(n)cthar groups of thar s (map 7), formerly royal officials and suppliers. Still more peripheral from the center are the various farming thar s, the Jyapus (map 8), who fill most of the city's area except for the Brahmans' area and those portions of the Chathariya and Pa(n)cthariya area adjoining the east-west road, the city's bazaar, where the Chathariya and Pa(n)c-

Map 7.

Space and status. The area of settlement of Chathar and Pa(n)cthar households. They occupy the city's central sector. Com-

pare the distribution of Jyapus in map 8. Map courtesy of Niels Gutschow.

Map 8.

Space and status. Jyapu household. These households overlap the Chathar and Pa(n)cthar areas to some degree but are most

densely situated in the areas of the city peripheral to those settlements. Map courtesy of Niels Gutschow.

Map 9.

Space and status. Butcher households. The households of the Naes (butchers) are located along the edges of the built-up area

of the city. They are conceived to be within the symbolic boundaries of the city. Map courtesy of Niels Gutschow.

thariya have their shops and, often, adjoining houses. At the very periphery of the farmers' area, and forming a ring around the outer extremes of the city, are the houses of the butchers (map 9). Finally, outside the city to the inauspicious south, live the untouchable sweepers, the Po(n)s (map 4, above).

The hill on which Bhaktapur is built has a broad plateau at its summit with no visible distinctly highest spot. The Malla palace and Taleju temple are situated on a plateau that is bordered by slopes that gradually descend some twenty meters to meet the fields outside the boundaries. This slope adds a dimension of top-down to the imagery of central to peripheral. The highest spot of the plateau at 1,339.8 meters (slightly higher than the site of the palace at 1,335 meters) lies just to the west of the Tripurasundari pitha , the central mandalic[*] shrine, and during the twelfth to sixteenth centuries was apparently part of the site of the large Newar Royal Palace compound of the day, Tripura (Slusser 1982, vol. I, p. 204). At that time the highest point in the city was, in fact, within the royal precincts.[16]

Detailed maps of the location of the various craft thar s, which are ranked in the lower segments of the Jyapu and below, made by Guts-chow and his associates (Gutschow 1975; Gutschow and Kölver 1975), show the occupational castes distributed in various ways, generally throughout the city, except for the central area, the area of the palace, the main Brahman cluster, and the central portion of the Chathariya and Pa(n)cthariya settlements. The craftsman areas are in the outer portions of the Chathariya and Pa(n)cthariya areas and throughout the area of Jyapu settlement. The number of settlements of any one thar vary. The Chipas or dyers, for example, have only one settlement, but other professional thar groups have several. The Kumha:s, potters, for example, have one large settlement in the south, and two in the northeast of the city. The oil pressers, or Sa:mis, have four dusters, two toward the east, and two toward the west. The barbers, or Naus, live in six clusters throughout the city. The house masons, the Awa:s, have three settlements, one to the west, and two to the northeast. The Jugis live (map 10) in an irregular pattern with some central clustering within the city, cutting into and intermingling with the Chathariya, Pa(n)cthariya, and farmers' areas. This inner location of the Jugis is in striking contrast with what might have been expected in the status gradient from center to periphery signaled and created by the arrangement of the most centrally important thar s in the city hierarchy, and in marked contrast to the external position of the Po(n)s, who along with the Jugis are

Map 10.

Space and status. Jugi households. In marked contrast to the Naes and the Po(n)s, the Jugis are distributed throughout the

city. They are the city's internal absorbers of pollution (chap. 10). Map courtesy of Niels Gutschow.

the central foci of ideas regarding pollution (chaps. 5 and 11). The position of the Jugis, as we will see, seems closely related to aspects of their significance in the city order.

In contrast with the other spatial features discussed in this chapter, the center-to-periphery, top-to-bottom, arrangements of status are not used or emphasized in the course of the city's symbolic enactments. The royal center is a focus in the city's two major festival sequences (Mohani and Biska:) and the untouchables' quarter has occasional symbolic representations, but the overall spatial status arrangements, insofar as they do reflect a symbolic order, are not given further representation.

The Village in the City, The Twa:

Binode Dutt ([1925] 1977, 147) wrote that in traditional Hindu city planning the main streets or Rajapathas of the city divided it into a set of "wards," called grama s. In some traditional towns "the same caste or people of the same profession were congregated in the same ward. . . . Every ward was set apart for a caste or trade guild of note which enjoyed an autonomy of its own" (ibid., 147). In other (according to Dutt, larger) towns or cities, as we have noted, these "wards" were the sites that contained a mixed, and, in part, functionally integrated, selection of "castes" and occupational groups, and which were "prototype[s] of the whole city on a smaller scale." "Grama " is a common Sanskrit term for village[17] and is the term for village in Nepali. In some traditional town plans the grama s were assigned to, and named after, different presiding deities (ibid., 143). These urban grama units are called twa: in Bhaktapur Newari (twa: in Kathmandu Newari and tol[*] in Nepali).[18]

Gutschow and Kölver (1975), like Dutt, call these units "wards." As they note, this is a somewhat ambiguous terminology as Bhaktapur has recently been divided into seventeen "wards" for modern administrative purposes by the central government. These wards do not correspond to the twa: divisions. The problem of English nomenclature comes in part from a problem in using the tempting gloss "neighborhood," in that some of the major twa:s are further subdivided into smaller areas, also called "twa:s " (when the context is clear) which are clearly neighborhoods. When a contrast with these smaller units is needed in Newari discourse the term matwa: is used for the large and major twa: s, the

prefix ma deriving from the trunk of a tree of which the smaller neighborhood twa: s are branches.

Bhaktapur is always said to have twenty-four major twa: s,[19] and these have various ritual representations. These have probably shifted somewhat over time through splitting and coalescing, but our map (map 11) is a close approximation to the traditional matwa: s. Accepting the traditional number of twenty-four matwa: s, an average twa: would consist of about 270 households and about 1,600 people. It is perhaps significant that these numbers are equal to the median population of Kathmandu Valley Newar towns or "compact settlements" (His Majesty's Government, Nepal 1969, 81). The average number of houses in a twa: also happens to fall within the range given in classical definitions of a grama . Kautilya[*] gave a range of between 100 and 500 houses as defining a grama (Slusser 1982, vol. 1, p. 84). However, in comparison with classical grama s, which were distributed over a large area, the Mauryan grama , having an area of from two to four square miles,[20] the otherwise analogous twa: s of the Newar cities are compressed into densities more than ten times more compact.

As Auer and Gutschow have pointed out, if one asks a Bhaktapur Newar where he lives he often answers with the name of his twa: . This is one of the important loci of his identification. There is a well-known Newar saying: "If the household is in proper order, the twa: can be 'frightened off' (khyaegu ); if the city is in proper order, the country can be 'frightened off.'" "Khyaegu ," "frighten off," has the sense of chasing away a cow that enters a field, or an intruder into a courtyard. In these successively inclusive units, whose boundaries must be protected at each level, the twa: takes its important place between the household and the city.

Gutschow and Kölver (1975, 26) described some of the general characteristics of Bhaktapur's twa: s:

As a rule, a . . . [twa: ] will be centered around a spacious square. This is usually paved and serves various agricultural and commercial purposes: during and after harvest, it is a threshing floor, a space for winnowing grain, for drying rice and certain other vegetables. . . . In potters' wards, unbaked jars or pots are placed there for drying. Women will here prepare the warp before weaving. Almost all squares are hemmed in by arcades, where people will congregate in the evening for various social purposes. . . . In most wards, the central square has a well. A temple or shrine to Ganesa[*] [is] found in every ward.

Map 11.

The village in the city. The major twa:s. Note that the boundary between the upper and lower cities follows twa: boundaries.

The main east-west thoroughfare and bazaar street bisects the city. The city's festival route (see map 12) runs through all of these twa:s

except the most westerly one, Bharbaco. The numbers on the maps refer to the following twa:s: (1) Bharbaco, (2) Itache(n), (3)

Tekhaco, (4) Khauma, (5) Ma(n)galache(n), (6) Laskudoka[*] , (7) Bolache(n), (8) Lakulache(n), (9) Ta:marhi , (10) Kwache(n), (11)

Yalache(n), (12) Tulache(n), (13) Tibukche(n), (14) Coche(n), (15) Yache(n), (16) Gwa:mharhi, (17) Bholache(n), (18) Thalache(n),

(19) Tachapal, (20) Inaco, (21) Kwathandu[*] , (22) Gache(n), (23) Taulache(n), and (24) Je(n)la. Map courtesy of Niels Gutschow.

They note that the "wards" usually have their own shrine of the deity Nasadya: (chap. 8) and often one of Visnu[*] , but these are secondary in their specific importance to the twa: to its Ganesa[*] shrine. Gutschow and Kölver's mention of the "potter's ward" reflects the fact that although all twa: s have at least some mixed occupational and status membership, one group may dominate the twa: numerically, and may sometimes give it a local flavor and identity.

Twa: s vary not only in the details of their membership, but sometimes in identifiable aspects of their spoken language, and, in popular conception at least, in the behavioral style of their members, their "manners" (cf. D. R. Regmi, 1965, part II, p. 554). Twa: s, or their major segments, are the face-to-face communities beyond the extended family where people know each other personally and where mutual observation and gossip are important sanctions. It is here that children's play with nonfamily children and adult associations with non-phuki members provide the ground for the considerations of mutuality and equality and for judgments on personal qualities that compete with or influence hierarchical orientations. The reason that the household must be organized to chase off the twa: , as the saying puts it, is that the twa: , or one of its neighborhood subdivisions, is the place where individual or family misbehaviors are likely to be first known and of considerable interest and where family reputation, or "face," ijjat , is at risk.

The twa: is continuously represented for its inhabitants in symbolic actions. Like most units in the city (as we will discuss in the chapters on calendrical events), the twa: is sometimes represented as a significant locus for action, as a maximal unit in itself, and sometimes in a kind of "parallel" representation as one of a set of similar units that are all doing the same thing at the same time or in sequence, and thus indicate their equivalence as categories and, at the same time, their significance as units constituting the city. The most salient inner representation is the twa: 's central shrine of Ganesa[*] . Ganesa[*] must be worshiped as a preliminary to all important household ceremonies and all rites of passage. Some twa: s also have a special protective deity in addition to their central Ganesa[*] . This may be Bhairava or a form of the Dangerous Goddess. In some twa: s the protective goddess is worshiped once a year, and carried on the processional route of the twa: (chap. 13).

Twa: s have some ordered relationships to the larger city. We may recall Oldfield's report that the number of gates in the old Newar city walls "corresponded exactly with the number of squares (toles) within

the city, . . . each gateway being associated with a particular square, and placed under the municipal control of the same local authorities, who were as much responsible for the repairs and defense of the gateway as they were for the general management of the square" (Oldfield [1880] 1974, vol. 1, p. 95f., original parenthesis). We have also noted Guts-chow and Kölver's observation that each twa: has its prescribed route for carrying corpses to the cremation ground (1975, p. 27).

The twenty-four twa: s are represented together as constituative elements of the city in one of the climactic events of the annual festival cycle—the sacrifice of twenty-four male buffaloes to the Goddess at the Taleju temple during the autumn harvest festival of Mohani. Most of the central twa: squares are also in their proper annual turn the site for the ritual dance-drama of the Nine Durgas, the possessed dancers, whose movements during nine months through Bhaktapur each year are considered by many to be Bhaktapur's most important symbolic performances (chap. 15). These twa: -based dramas deliver, as we will argue, some of the city's most powerful messages about the proper moral integration of individuals into the ordered life of the city.

Some Notes on the Symbolic Construction of the House

We have so far been moving into successively smaller spatial units. When we reach the house, we are at the boundary of one of the city's (here, literally) walled-off units, whose internal organization is hidden as far as possible from larger units, whose integrations and controls are largely internal, and whose concern to the larger city is in their public outputs. Although the symbolic organization of the house, like the life of the households within it, is, of course, elaborately influenced by Newar culture and tradition, it is for our purposes here, "below" or "outside" the level of public city life, and is part of the host of smaller private forms that are sometimes consonant with, sometimes antagonistic, sometimes irrelevant to the integrating forms of the public city. The interiors of these units—and above all the life within the house—reflect larger public institutions and arrangements, stand against them, prepare members for them, defend members and console them against them, and punish and reward members in their own ways and for their internal needs as well as the needs of the larger system.

This chapter is a convenient place for a summary description, making much use of others' studies,[21] of some spatial characteristics of the

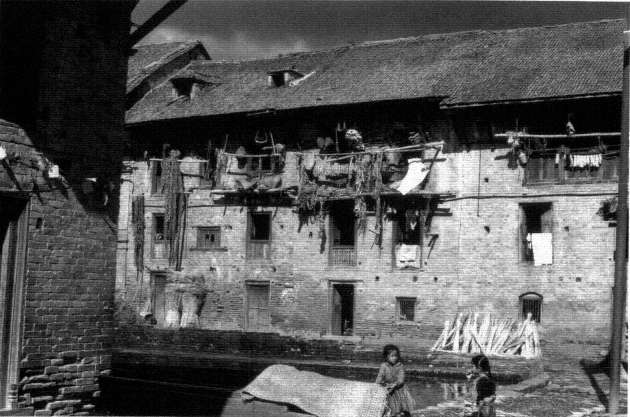

Figure 8.

Farmers' houses. Adjoining houses of families of one Jyapu phuki.

Bhaktapur Newar house (see fig. 8), sharply bounded from outer city space by a precisely marked symbolic boundary. The ideal Newar urban house is built, repaired, and lived in by the middle and upper thar s, and those members of the lower thar s who can now find the money for it. The poor, notably the Po(n), live in much simpler ones, often single-story thatched houses. The ideal traditional Newar house consists of four, and occasionally five, stories. It is constructed by means of a wood frame and beams and thick supporting walls of fire baked bricks made of valley clay held together by a mud-based mortar.[22] The roofs, traditionally of tile and now sometimes of metal sheets or wheat straw thatching, slope from a peak towards the front and back, the peak, being at the long axis of the rectangular (as viewed from above) houses. The eves are supported by external struts that buttress the roof against the walls of the house; on a few houses these struts are elaborately carved. The upper story opens out into a porch, the ka:si , of occasional important ritual use, including the worship of the sun (chap. 8).

The house is internally divided longitudinally into two equal halves, front and back, by a division that runs parallel to the front of the house and consists of a wall in the lower stories and columns in the upper ones. The sections formed by this middle division are called dya , and are designed as "outer" (pine ) or "inner" (dune ), with "outer" being the half on the street side. The inner half often faces on a central courtyard, which is ideally surrounded on all sides by houses of members of the phuki , or at least of the thar , although this pattern is often disrupted in recent building.

The house is symbolically set off at its boundary with the outer city, and its vertical space and horizontal space are used as resources for symbolic meanings. In its vertical dimension the house becomes progressively more sacred, differentiated, and vulnerable to pollution at progressively higher levels. The lowest floor of the house, the cheli , is, in fact, in some contexts "outside" of the house, a kind of bordering outside, like the zone just outside of the city's boundaries. The origin of the word "cheli " is uncertain. Manandhar (1976) proposes that it may come from "che (n )," "house," plus "di ," support. Some Bhaktapur scholars surmise, in what is perhaps a folk etymology but is suggestive of their sense of the connotations of the term, that it may be derived from "che (n )," "house," plus "li ," an "old term" said to mean the lower and impure part of the body below the umbilicus. Middle-status and lower-status families sometimes keep livestock on the cheli , but even

upper-status families often keep animals such as goats who are being kept for sacrifice, and sometimes pet animals, such as rabbits and turtles in this out-of-the-house space. It is sometimes said that animals kept on the cheli will absorb diseases and the malevolent influence of dangerous spirits trying to enter the house and will thus protect people in the upper part of the house.[23]

The "outside" status of the cheli is further shown in that people from polluting thar s were—and for the Po(n) this is still true—allowed to enter the cheli , but were forbidden to go any higher into the house, which would have been polluted by them. Work areas for occupational castes and shops are often located on the cheli level of houses and are adapted in various ways. The cheli is also often used for the storage of materials that are said to be "not worth stealing," such as firewood, straw, hay, bricks, and old furniture.

The next floor (the second floor in the American system of designation, which will be used here), is the "floor of the mata (n ) (or mata [n ])," the mata (n ) tala . This second story is the entrance to the first of the house's internal and progressively more inward areas. It is reached from the cheli by an interior stairway, which must be placed so that persons using it do not face the inauspicious direction south. On the mata (n ) ordinary visitors (those who are not family members or of higher status than the family) and friends of junior members of the household are received. The mata (n ) story is divided by a longitudinal partitioning wall, producing a large front room running the length of the house and facing on the street. This is the mata (n ) proper, although in other contexts the entire floor may be referred to as the mata (n ). The back half is divided by perpendicular secondary walls or partitions into small rooms that serve as sleeping quarters and storerooms for valuable goods.

The next higher story is the "floor of the cwata ." The longitudinal dividing wall is represented here by columns, so that the entire floor is open, and constitutes a large "hall," the cwata . Traditionally in high-status houses, and still remaining in many old houses, large carved ornate trellis windows (one of the representative forms of Newar art [S. P. Deo 1968-1969]) were located here, allowing people to look out on the streets without being seen. It is on this floor that the formal feasts associated with many family ceremonies, particularly for auspicious rites of passage, are held and high-status guests are received. In Brahman, Chathariya, and some Pa(n)cthariya houses this floor (or sometimes the floor above it) is the site of a shrine of the Tantric lineage goddess, the Aga(n) God (hidden in a room of its own), in accordance

with the ideal that that shrine should be located toward the physical center of the house. The cwata is also the place where important Brahman-assisted family worship is usually held. Such worship is associated with rites of passage, and with some major festivals and other ad hoc special occasions (app. 4). Some members of the household, often the older ones, sleep here and there on bedding on the unpartitioned cwata .

The household shrine and images of household gods, in contrast to the Aga(n) God, are placed at one of the highest levels in the house. This is usually on the next highest floor, which is often the top floor, the "floor of the baiga ." This is usully under the overhanging eaves of the house and is the location of the cooking and family eating area as well as the household shrine and its associated equipment. Daily household worship is held here and, occasionally, Brahman-assisted rituals if the group involved is small and does not include people from outside of the household or phuki group. Many houses have a fifth story. In this case the floor above the cwata is called a "fourth floor," and the top floor is still called the baiga (Korn 1976, 23).

Korn (1976, 3) provides a useful sketch of the typical furnishing of a Newar house:

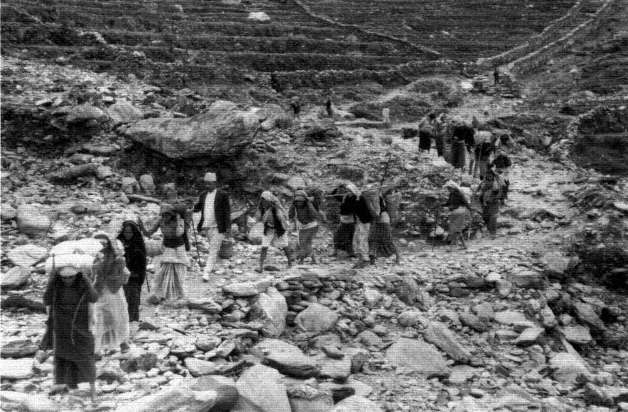

The interior furnishings and decorations are very simple in contrast to the often extravagant facades. After the clay and tile oven, the most important is the all-purpose straw-mat which serves as a carpet during the day and for sleeping on during night. Other carpets and blankets may decorate the floor, but these are reserved only for eating on special occasions. In the morning the bedding of blankets and cotton rugs is rolled up and stored away. Clothing and valuables are kept in wall recesses and wooden chests. A stove as a heating apparatus is unknown, and in its place portable clay bowls of various size are filled with burning charcoal. The kitchen is seldom used as a meeting place. Clay or metal oil lamps, available in many different shapes and sizes, stand in wall recesses to give light during the dark hours. Stocks of rice and other grain are stored in wooden chests or clay pots, while potatoes and vegetables are kept in bamboo baskets hanging below the overhanging roof. Clay and brass pitchers are used as water utensils. Wood, carried into the town from hills by porters, is the usual heating fuel although the poorer people burn dried cow dung. Foreign influences, however, have recently introduced Western-style furnishings. Electricity and kerosene have simplified the tasks of cooking and lighting.

In horizontal space the house's boundary with an exterior encircling space is indicated by a stone placed about two to three feet before the front door, under the forward edge of the front overhanging eaves. The

stone, the pikha lakhu (which is also the term for the area it covers), is considered to be the seat of a protective divinity (chap. 8). The pikha lakhu is used in many rites of passage as the division between the inner world of the household and the outer world. It is here that a bride is greeted by the chief woman of the household to be purified of spirits and malevolent influences before being conducted into the house. It is at the pikha lakhu that the corpse of a household member is left for a moment and then is picked up by the members of a funeral guthi to be carried to the cremation grounds. The pikha lakhu is cleansed and purified each morning, as other god images in the house are, and it is also purified before major household worship.