Chapter Sixteen

The Patterns and Meanings of the Festival Year

The state is concentric, man is eccentric. Thence arises an eternal struggle.

—James Joyce, conversation cited in James Joyce, by Richard Ellmann, 1982, p. 446.

Introduction

In our discussions of Bhaktapur's focal festivals, of the Devi cycle, and of the performances of the Nine Durgas, we have illustrated various ways in which social units, space, actual history and legendary history, gods, and time are woven together in an eternally returning annual cycle. The major festivals are surrounded by a mass of lesser calendrical events whose symbols and activities are more limited, often seemingly unrelated to other annual events or to the larger city order. Our task in this chapter is to examine the entire collection of annual events in a quest for possible order of one kind or another among them.

To facilitate such an overall view we have summarized the year's events, added comments on different phases within the yearly cycle, and placed events and comments in the context of the annual lunar calendar in appendix 5.

Distinctions and Enumerations and Their Implications

We can make a first approach to the year's collection of annual events by summarizing and enumerating, where possible, some of their distinguishing features.

1. In the course of a year there are seventy-nine named annual events, occasionally grouped so that there are more than one in a day, and with

one event lasting two days. The seventy-nine events thus occupy to some greater or lesser extent seventy-four days.[1]

2. These seventy-nine annual events are of greatly differing importance. On the basis of the comparative amounts of city personnel, space, resources, and time devoted to them, as well as our opinion of their significance to Bhaktapur as a city, we have sorted the annual events into those of major, moderate, and minor importance. It is fairly easy to discern at the two extremes major events and the often very trivial minor ones, but the inclusion of an event in the middle category, "moderate importance," is often somewhat arbitrary. At any rate, our sorting gives us twenty-five major events (many of which we grouped into "focal" festival sequences), twenty-eight events of moderate importance, and twenty-six events of minor importance among the year's seventy-nine annual events. Thus we have some fifty-three events that we take to be of some more than minor annual importance to the city.

3. If we sort the annual events by the social-spatial unit, which is emphasized, we find that only two such events are primarily occasions for individual activities, that is, vratas ([42] and [43]). Twenty of the seventy-nine annual events are of primary concern to the household —although many other events entail household activities that are secondary to some activity in the public city. In contrast to household-centered events (and in contrast to a predominant emphasis in rites of passage), only two events may be said to be directed primarily to the phuki , but one of these is the fundamental phuki -defining Dewali [30].[2] The majority of annual events are those fifty festivals of various kinds located primarily in public city space . Four annual events have their loci out of the city , and there are an additional two such events attended by those whose loss of a parent makes them unable to worship a father or mother in the two annual household ceremonies devoted to their worship. Finally there are two events ([18] and [34]) whose spatial location is ambiguous for this classification, the latter case—not exactly an "event" in the same sense as other days—concerning both the household and the phuki .

The "primary" annual household events, in contrast to the household phases of rites of passage and to those household pujas motivated by some specific familial problem, are generally observed by all city households on the same day, and are in this sense "city-wide" events. Thus, almost all the annual events are either such parallel household

events or take place in the public city space, and may be amalgamated together into a class of civic events emphasizing the public city and households as units of that city. On closer inspection, as we shall see, these household events and events in public city space are differently related to civic life.

The primary household events insofar as they take place in parallel throughout the city are civic events, but in another distinction they take place below the level of the public city. In such a view, certain annual events—and segments of particular events—are occasionally above the city level, many more are below it, but most are at the level of the city, the fifty events located in public space being, by definition, at that level. Above the city level are the melas where individuals from Bhaktapur join with individuals from other cities and from other ethnic groups in pilgrimages to one or another Valley shrine, all, significantly, located out of the major Valley cities. In melas Bhaktapur's participants escape their city and its particular order. Individuals join in a larger human community, refracting themselves against another context than the city's public order, the city being reflected only in its absence. The characteristic annual events below the level of the public city are the calendrically determined household events, centered, for the most part, on the moral life of the household and its benign deities.

One important difference between household and public events requires a repeated comment. Competent members of a household must (as an index of that competence) participate in its ceremonies, as phuki members must participate in rites of passage and other phuki ceremonies. But participation in public ceremonies is, for the most part, voluntary for the mass of observers (although not for the central actors). Thus public ceremonies must have their own special ways of motivating attendance.[3] We have discussed some of the sources of the attraction of the important performances in previous chapters. These include their aesthetic qualities, their mystery, their intriguing complexity, their sacred and supernatural auras and, in some cases, the thrill of their dangers. The vivid presence of a deity in human form, its living manifestation in the Kumari maiden or the Nine Durgas, is an almost irresistible attraction. Many of the stories, dramas, and symbolic forms of the festivals engage and fascinate because they have compelling psychodynamic interest and resonate with the personal psychological forms out of which the public citizen is constructed. The tales of the phallic snakes issuing from the princess's nose and the banging together of the chariots of Bhairava and Bhadrakali[*] in Biska:, the blood sac-

rifices of Mohani, and the echoes of human sacrifice in the Nine Durgas' pyakha(n) are vivid examples.[4]

4. The deities who are foci of the various annual events include all of the major members of the city pantheon, a few quasi-deities or supernatural figures who exist only for the purpose of a particular festival, and some social categories—e.g., father, mother—treated as deities. For the benign deities there are eight events devoted to Visnu/Narayana[*] (including here Dattatreya), four devoted to Krsna[*] , and one each to Jagana and Rama. There are four devoted to Siva—one as Pasupatinatha, two as Mahadeva, and one (his only primary appearance in a household event) as Mahesvara in conjunction with his consort Uma. Ganesa[*] is the focus of four festivals, Laksmi and Sarasvati of two each. Yama or his representatives have three; nagas , one; the Rsis[*] , one; the deified river, one; and the cow deity, Vaitarani, one. Family members are worshiped as quasi-deities in four events. The family priest is worshiped on one occasion as purohita , on another as guru .

The dangerous goddess Devi in one form or another is the focus of about twenty-two occasions of which ten are in the Devi cycle. (Three of the events in the Devi cycle do not refer directly to Devi but are essential components of that cycle.) Bhairava—in himself and not as the consort of Devi—is the focus of two festivals and in tandem with his consort, Bhadrakali[*] , at the center of the Biska: sequence, which lasts ten days. The dangerous deity Bhisi(n), who is conceptually isolated from the Devi-Bhairava group, is the central deity of one event.

All the city's major deities are thus the subject of one or more festivals during the year; they are all duly honored. But the extent and nature of the festival use of the various deities and types of deities are quite different. The dangerous deities are never the focus of primary household annual events,[5] but they are the center of more than half of the events in the public city, and of all the urban structural focal sequences. The remaining minority of the public festivals, those of the benign deities, are divided among those deities, with Visnu[*] having the largest number, eight—or sixteen if his avatars are amalgamated to him. Siva, the putatively predominant deity of the Shaivite Hindu Newars, is, typically, hardly represented at all for the purposes of the on-the-ground concrete work of the festivals. His major festival Sila Ca:re (Sivaratri [15]) taking place, for the most part, at a pilgrimage site elsewhere in the valley.

While the festivals in the public city of the benign deities, whose

exemplary figure is Visnu[*] , are often said to be "in honor of" those morally representative figures, the public festivals of the dangerous deities not only honor and display those figures, but in contrast to the festivals of the benign deities, do something more. These are the public urban festivals, which are sometimes said to be not just for the gods but "for the people." These festivals make use of the special metamoral force of the dangerous deities as guarantors of order.

Not every event has a focal deity—some half dozen events are simply annual occasions for doing something or have some reference to a demonic or legendary figure (e.g., [45] and [65]) with references to major deities only in the far background.

5. Some annual calendrical events are of particular concern to certain categories of people in Bhaktapur—students, women, farmers, upper-level thars , merchants, Brahmans, people who have been bereaved during the previous year. The vast majority of the events concern all of Bhakatapur's people, however, with the traditional exception of the most polluting thars . A different question, however, is the representation of the city's various hierarchical macrosocial roles in the cast of characters of the festival enactments. In most cases the human actors on the public stage are simply the pujari attendants of the focal deities and the musicians (usually from one of the Jyapu thars ) who may accompany the deity in its procession. Thus the vast majority of public festivals do not represent the divisions of the city's elaborate differentiated macrostatus system. It is only in the year's two major festival sequences, Biska: and Mohani, that there is some complex and differentiated representation of Bhaktapur's macrosocial status system. Yet, even here the representation is sketchy. The king and his chief Brahman are given some centrality, and the court, other priests, farmers, and polluting thars are represented, but for the most part these actors are simply used as a clumped and static resume[*] of the city's ranks. The focal festivals do not, with one or two trivial exceptions, show any dramatic relations among actors characterized by their social statuses. Whatever the dilemmas, paradoxes, conflicts, and problems that are explored in the annual festivals, the components of Bhaktapur's social system are privileged and taken for granted. The levels and the other components of the macrostatus system are not used to provide agonists in the drama, not used to illustrate conflict and its possible resolutions. In the midst of all the drama of annual events the hierarchical system of social statuses is protected, represented only as a unified actor, an actor who

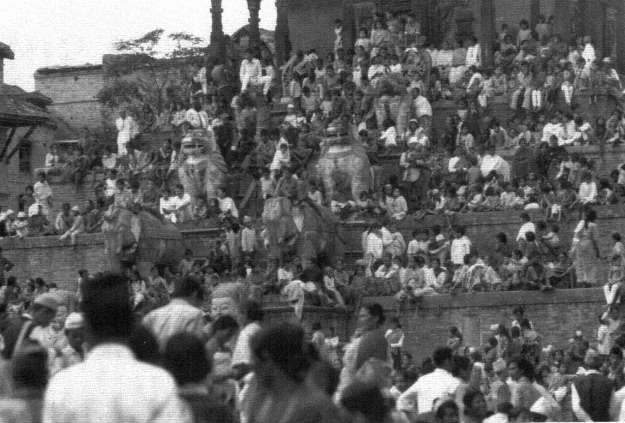

Figure 34.

Spectators seated on the steps of the Natapwa(n)la temple in Ta:marhi Square to watch the struggle to pull the

Bhairava chariot.

is, sometimes, as is the case pervasively throughout city symbolism, put in contrast with an "external" and oppositional social actor, the untouchable. The potential drama of the interplay and conflicts of macro-statuses is deflected and played out elsewhere—not in the symbolic enactments of the annual events, whose surfaces and middle depths, at least, speak of other dramas.[6]

It has been said of some of the festivals of the Hellenic pagan cities of the second and third centuries A.D. that they "showed off the city in its social hierarchy: people processed in a specified order of social rank, the magistrates, priests and councillors and even the city's athletic victors, if any" (Fox 1986, 80). Those festivals seem to have not only represented the city's statuses but also celebrated the particular citizens who temporarily captured roles in the hierarchy. The particular individuals who occupy the roles in Bhaktapur's largely ascribed—not achieved—status system do not need to be supported by such public advertisement. If Bhaktapur's social system is represented only in its unity, the individuals who happen to hold these statuses are completely dissolved in the immemorial roles they play in the annual festivals.

In summary, most (some 63%) of Bhaktapur's annual events are in the city's public space, with the calendrically coordinated household festivals following in quantity (25%). Almost, but not quite, all of the annual events have direct reference to deities, the annual calendar being largely a "religious calendar." The dangerous deities only appear when the primary or only locus of the event is in public space, but they are then dominant. And, in contrast to the minutely detailed dramatic interactions of various city spaces, of spatially located social units, of deities and times, the macrosocial system is portrayed only as a unified presence in the dramas of the yearly calendar.

A Note on Moving Deities Within the City

When the city's spaces and what they represent are tied together or contrasted in a serial, interactive manner rather than in a parallel summative way, the characteristic device used is the jatra . The deity is either moved systematically so that masses of people may be brought into contact with it, or else—less commonly—masses of people move systematically to encounter a deity or a sequential set of deities. These movements, jatra s, follow traditional routes, variously tying together

units of the city and, often, the city as a whole. They explore central points, axes, and boundaries, as people move or as focal deities are carried through space and time. In so doing the procession of people or of the deity is often brought into an encounter with other kinds of dramatic enactments.

By far the most common movement is that of those jatra s that move the deities themselves. Such movements would seem to be a utilization of an unremarkable resource for the enactment of symbols, for putting symbolic forms into effective relations with space and community. Yet, an observation by Walter Burkert suggests that such jatra s are, in fact, problematic in comparative perspective. Burkert writes of ancient Greece that "processions with images of gods—which play a major role in the Ancient Near East—are [in Greece] an exception. . .. Such a moving of the immovable is an uncanny breaking up of order " (1985, 92 [emphasis added]). Bhaktapur's gods leave their temples and their fixed positions, and although they do not wander at will in the course of the annual events, their order is a mobile order. The contrast with Greece suggests that the movement of Bhaktapur's gods—or at least of the jatra images they inhabit—out into the city from their fixed bases in the city are invasions, albeit controlled and not chaotic ones, of what in Greece was becoming a safely secular space.

Patterns in the Year

What happens if we reassemble the three cycles that we separated from each other in previous chapters and attempt to examine the narrative movement of the annual cycle as a whole (see app. 5)?[7] We must now look for disjunctions suggesting phases and movements in the year's course, for frontiers indicating some difference in the festivals that precede and follow them. Let us begin by making a cut into the annual cycle after the ending of Mohani in early October. Although the successful rice harvest had been compellingly represented in the themes of Mohani, the actual harvesting continues. The work of Devi has now been given over to the Nine Durgas. Taleju returns to the secret inner recesses of her temple, and there will be no more festivals of the Goddess nor of any other dangerous deity (except for the merchants' Bhisi[n] festival)[8] for a span of six lunar months, when the solar festival, Biska: will reintroduce the Dangerous Goddess and her consort Bhairava. Then, beginning with Biska:, will come the six months during which all the public festivals of Devi and her various forms and associates and

those few of the unaccompanied Bhairava will occur, as well as, in fact, the great majority of the year's festivals. The ending of Mohani, the symbolic culmination of the cycle of rice agriculture, then, returns Devi to the city in the form of the wandering Nine Durgas, but marks the end of her public presence in the annual calendrical events for the next six months.

The first annual event after Mohani is the lunar new year sequence, Swanti [77-2]. When considered in its contrast to the year's other events, Swanti begins the lunar calendrical year with a turning in and centering on the household and its members. Swanti's interactive solidarity is internal to the household, with a secondary parallel solidarity relating each household to all Hindu (and with Mha Puja to all Newar) households as well as to the households of Bhaktapur itself. The Swanti sequence uses as the antistructure that serves to define the household, not the city in which the household is embedded, but still another realm beyond the household, that of death personified as Yama, at the threshold of an afterlife determined by an individual's moral and ritual activities. The environing city is irrelevant to this opposition and to the resulting dialogue between household and Yama. The lunar New Year thus constitutes still another sort of annual frontier, beginning the voyage through the year that follows it with the positioning of individuals in the basic moral cell of the city, the household.

Swanti is followed first by a pilgrimage and mela at a Visnu[*] shrine out of the city [3] and then—nine days after the end of Swanti, and ten days after the New Year's Day itself—by Hari Bodhini [4], the day of Visnu's[*] awakening from his four month's cosmic sleep, which is celebrated by still another out of the city mela . Gaborieau (1982 [summarized above in chap. 12]) had proposed the falling off to sleep and awakening of Visnu[*] as marking off an annual period of four months, dividing off from the rest of the year a special segment, an out of the ordinary time, a period beginning with profound disorder and culminating in regeneration. In Bhaktapur Hari Bodhini in itself does not mark a shift in the year's activities from the extradordinary to the ordinary—Mohani did that. Nor does the day of the onset of Visnu's[*] sleep, Hari Sayani [42]. Yet, aside from its exact timing and duration, Gaborieau's proposals about the year's phases have some relevance to Bhaktapur and we will return to them.

From the end of Mohani in Kaulathwa through the lunar New Year some two weeks later and then on through the succeeding nine fortnights there are relatively few annual events, all of them, except for the

Suku(n) Bhisi(n) God Jatra, focused on the city's benign moral deities. This changes with Pasa, Ca:re on the fourteenth day of Cillaga (March), when, with an emphasis on protection from evil spirits, the first animal sacrifices since Mohani—again with the exception of those made by merchants to Sukhu(n) Bisi(n) God—are made to Taleju in the Taleju temple and to some Aga(n) Deities, initiating a "period of anxiety" that will last through the remainder of the year until the end of the following Mohani. In this period the festivals of the dangerous deities will take place. Thus Pasa Ca:re is or anticipates still another frontier for the year. That frontier is more clearly signaled in the elaborate public festivals of the Biska: sequence, which comes (depending on the relation of lunar and solar calendars) some twelve days later. Biska:, which comes about six months after the end of Mohani, is the first of the public urban festivals that after the six intervening months center once again around the dangerous deities. Biska:, the solar New Year festival, contrasts sharply with the lunar New Year sequence. While Swanti emphasizes the household and the relations of individuals in the household, and is characterized by a sort of withdrawal from the city into the household, the solar New Year festival—with its themes of urban division and reunification and of the sacred legitimization of the city's space—emphasizes the city itself. In the solar New Year the household is secondary. The deities emphasized in the lunar New Year's sequence are the benign moral gods—Laksmi and quasi-deified family members in the interior of the family and at its exterior and, in fact, continuation, death as Yama, the judge and executor of each individual's morally created and deserved fate. In Biska:, in contrast, the deities are the amoral dangerous one. In contrast to Swanti, what is contrasted with the household and given primacy in Biska: is the larger nested set of urban units that surround the household and enable its survival as an element in Bhaktapur's society. Thus, Biska: begins a six-month phase of the year when the ordering of the household's sustaining "lateral" environment,[9] the public city and its environment is explored. This exploration has, in turn, two phases.

In the weeks following Biska: there are a few heterogeneous events of varying importance—worship of mothers in the household, jatra s of forms of Devi, and one especially auspicious day. Three fortnights after the end of Biska: comes Sithi Nakha [36], the first event with a reference to the annual rains and the rice growing cycle. Sithi Nakha is preparatory; it will be the second event in the Devi cycle, Bhagasti [40] in June, which marks the beginning of rice planting, and which is another im-

portant transition in the year. The annual festivals of dangerous deities had begun again with Biska:. Now on Bhagasti, Devi's agents in the city, the Nine Durgas who had begun their cycle nine months earlier with the last of the Devi festivals, the focal Mohani, disappear—in some versions go into the ground—for seven fortnights.[10] With the disappearance of the Nine Durgas there is a shift of concern among the important "anxious festivals" of the period from the internal dangers to the integration of the city to the external environing dangers so clearly represented in the successes and failures of the monsoon rains and the rice cycle. These concerns with the city's external and supporting realms will endure for three-and-a-half months, during a period of an increasing density of annual events, until the end of Mohani. Bhagasti is followed by a five-week period of licensed obscenity, culminating in Gatha Muga: Ca:re [45]. During this period there is a minor jatra of an avatar of Visnu's[*] and then Hari Sayani [42], the beginning of Visnu's[*] four-month cosmic sleep. Like his awakening on Hari Bodhini, this is not in itself a transitional event in the annual cycle. Hari Sayani is followed by a minor event, Tulasi Piye [43], related to Visnu[*] (which gives an omen about the length of a worshiper's life), a minor household puja (Guru Puja [44]), and then by Gatha Muga: Ca:re [45], marking the ideal completion of the transplanting of rice to the flooded paddy fields.

Gatha Muga: Ca:re is followed by a fortnight with only one event. That one, Naga Pa(n)cami [41], is intended for the protection of houses and households from dangerous nagas . Then the next four lunar fortnights become filled with events; they contain thirty-one of the year's seventy-nine festivals and thus constitute the most concentrated festival span of the year. This period contains a mixture of types of events—public and household, devoted to both benign and dangerous deities. However, within this diverse group there are two major events. First comes Saparu, with its active support of the progression of the spirits of the recently dead into King Yama's realm and its accompanying "anti-structural" carnival. Second is the focal structural Mohani, culminating the year, celebrating and miming the power of Devi in Bhaktapur's supporting world, and drawing her into the city's center of royal power.

The festival cycle as a whole does, then, seem to have some overall patterning. One of its most striking aspects is the division of the year so that in the six months from Mohani until some twelve days before Biska: there are relatively few events (twenty of the year's seventy-nine). These are with one exception—the generally anomalous Sukhu(n) Bhi-

si(n) God Jatra [8]—devoted only to benign deities and lack the anxious themes of many of the annual events that will follow. Then, after an anticipation in events with reference to dangerous spirits and protection of the body (Pasa Ca:re [18] and Cika[n] Buyegu [19]), Biska: introduces the long season of the festivals of the dangerous deities, of the Devi cycle, and of events with primary and central references to protection and to death. Aside from the festivals of the Devi cycle, there are some fifteen additonal such events during this period. Mixed in with these events exclusively characterizing these six months are thirteen "ordinary" festivals, primarily minor ones "in honor of the gods" of the sort found throughout the other half of the year.

Within the span of six anxious months between Biska: and Mohani, the death and disappearance of the Nine Durgas during Bhagasti some two months after Biska: marks a shift in the emphasis on the dangerous deities, primarily Devi, from their roles as the representatives and protectors of urban spatial units (epitomized in Biska:) to their use in the representation of—and the mediation with—the noncivic encircling en-viroment. In this perspective there is a movement from household in Swanti to the public city in Biska:, and then to the city's vital environment after Biska:, this final shift having its resolution in Mohani.

To return finally to Gaborieau's specific suggestions about the structure of the Indo-Nepalese festival year (see chap. 12), the shifts within the six-month Biska:-Mohani, period, starting with Bhagasti and ending with the end of Mohani, three-and-a-half months later, correspond roughly, that is, within a few weeks, to the period of Visnu's[*] cosmic sleep. Visnu's[*] sleep and awakening do not in themselves delineate any shift, however, nor is the period of that sleep (Caturmasa) of the same significance in Bhaktapur as an "inauspicious period" as it is, reportedly, elsewhere. The span from Bhagasti to Mohani can, nevertheless, certainly be characterized (as Gaborieau does for the period of Visnu's[*] sleep) as a time when "the earth is left to the demons." In addition (further paralleling Gaborieau), there are major festivals of "reversal" early in the period (the five weeks between Bhagasti [40] and Gatha Muga: Ca:re [45], Gatha Muga: Ca:re itself, and the carnival phase of Saparu [48]) and a major festival of "regeneration" (Mohani itself) toward its end. The span does not divide neatly into a "reversal" half and a "regenerative" half, however, being full of a miscellaneous variety of festivals. It is really only certain events that are clearly (the first ones) reversals and (the last) regenerative. What Bhaktapur seems to show, in

contrast to Gaborieau's proposal of an Indo-Nepalese "normal" period of eight months followed by an "out of time" period of four, is an addition to the "normal" festival cycle that had held undisturbed for the prior six months of something more in the remaining six, an addition first of the urban ordering festivals of the dangerous deities, and then of a span that is "out of time" in the sense that attention turns to the exterior of the city, and its actors and its order. The last move seems prodded by the obsessions of the rice growing cycle and to be related to that cycle, as much as to the kind of abstract structural considerations argued by Gaborieau.

External Influences on the Annual Cycle

There are many possible external cyclical features beside the rice agricultural cycle that might have influenced the content and forms of the year's various annual events. These are the various aspects of the yearly solar cycle, the monthly lunar cycle with its phases of the moon and its bright and dark fortnights, and the various yearly patterns of weather and agriculture. The annual solar cycle, with its solar year, its seasons, its equinoxes and solstices, its "ascending" and "descending" halves, is almost unreflected in Bhaktapur's annual calendar. The great exception is Biska:, the focal solar New Year sequence centering on the vernal equinox.[11] In Biska:'s symbolism, as we have discussed, the possible references to the sun's behavior and to the solar year are minimal or equivocal.[12] There is only one other annual festival in the solar cycle—Ghya: Caku Sa(n)lhu [10]. It comes at a time which once elsewhere in South Asia traditionally marked the winter solstice and the beginning of the ascending half of the year, but such connections are entirely lost in the events of the day. Aside from a reference to "spring music" in anticipation of a spring still several weeks away in the course of the lunar event Sri Pa(n)cami [13] there are no other annual events which respond to, symbolize or express the solar year.

The lunar cycle provides, of course, the basic month and the basic structure of Bhaktapur's calendar. For the most part the days of the lunar month simply provide a counting device with no further meaning. Within each month the phases of the moon provide additional materials for possible symbolic elaboration. The full moon and the new moon (to a much lesser degree) are occasions for differentiated events as well as

regular monthly ones. Yet, once again these differentiated events seem to have no salient present symbolic reference to the light or the dark of the fortnight's culminating phase of the moon.

The phases of the moon allow, however, for a further differentiation of each month into waxing (or bright) and waning (or dark) fortnights. There is a marked difference in the quantity of events in the two kinds of fortnights. Thwa , the waxing fortnights, have throughout the year twice as many annual events as ga , the waning fortnights. The waning fortnights all contain a special day, the fourteenth or ca:re dedicated to Devi. This and the difference in quantities of events would suggest the possibility of some contrast of ordinary versus dangerous, or auspicious versus inauspicious between the two types of fortnights. Ancient Hindu South Asia was explicit regarding differences in the two half-months (paksa[*] ). . "The general rule is that the sukla paksa[*] [bright half] is recommended for rites in honor of gods and rites for prosperity; while the dark half is recommended for rites for deceased ancestors and for magic rites meant for a malevolent purpose" (Kane 1968-1977, vol. 5, p. 335). Bhaktapur's festivals do not sort neatly in such a way. There are festivals of the benign deities, of the dangerous deities and twa:s , and melas in both. Worship of living mothers and fathers is in the dark half, the Biska: sequence spans light and dark fortnights, and so does the Swanti sequence. Yet, the major festivals with reference to death, to the loss of order, and to "antistructure" are, in fact, found in dark fortnights, where they represent a large segment of those fortnights' relatively few events. These include Bala Ca:re [7], Sila Ca:re [15], Pasa Ca:re [18], Bhagasti [4], Gatha Muga: Ca:re [45], Saparu [52], Smasana[*] Bhailadya: Jatra [64], Pulu Kisi Haigu [65], Dhala(n) Sala(n) [66], Kwa Puja [77], and Kica Puja [78]. The events with reference to death in the bright fortnights are either secondary to the celebration of the household (as on the fifth day of Swanti),[13] or very minor (as in Yama: Dya: Thaigu [59] and Yau Dya: Punhi [62]).

The patterning of festival events by light and dark fortnights is not discursively salient. That is, although this patterning presumably gives a sense of meaningful order to the year, can be recognized by people when pointed out, and is probably known to some scholarly citizens, it must be pried out for the most part by an inspection of the distribution of annual events. The rice agricultural cycle and its enabling conditions, in contrast, is a salient and overt influence on the annual cycle. It not

only influences the distribution and sequence of various events (as the bright and dark fortnights do) but also enters into the content, stories, and symbolism of those events in direct and obvious way. Images of fertility and generation, of cyclical appearance and disappearance, of protection and destruction in an equivocal balance, and of capricious vital forces just beyond the urban order and just beyond the social selves of its citizens—all this expresses, responds to, and builds on the implications of the rice and monsoon cycle and their phases.

The annual rice agricultural cycle has reflections elsewhere in the calendar beside in the Devi cycle itself. One event, Ya: Marhi Punhi [9], comes when the annual consumption of the newly gathered rice harvest is about to begin. The benign goddess Laksmi is asked on this day to ensure that the rice consumed by the household will eventually be replaced. With the successful gathering in of the harvest, the emphasis has moved from the dangerous goddess of fertility to the benign goddess of the household stores. A major reflection of the agricultural cycle is in the shift that we have discussed at length in the kinds of events that occur in the segment of the year between the beginning of the rains at Bhagasti [40] and the symbolic end of the harvest at Mohani. The concentration of all kinds of events during this period in a sort of crescendo of symbolic effort and the large number of events related to death and antistructure are congruent with the problematic nature of this period of the year.

A View of the Annual Events With the Citizen at Their Center

The symbolic forms, events, sequences, narratives, and structures of narratives of the year's cycle comprise a substantial library of South Asian forms and ideas transformed and modulated so as to place Bhaktapur at their center. Yet, the yearly events from their humblest members to their most developed sequences of interrelated events speak to each of Bhaktapur's people not only of the universe as refracted and centered in Bhaktapur but also of the auditor-actor himself or herself in an attempt, so to speak, to deal with their eccentricity. The annual events, along with the city's other symbolic enactments, speak of being a "person" in Bhaktapur, a socially defined and placed and judged to be competent individual, a proper citizen. The annual cycle talks to the person of his or her relation to the household and its contained family,

to the extended family, to the city and its significant components, to a moral world beyond the city, and to still another world, an amoral or meta-moral world, beyond that.

The household within its arena, the physical house, is represented in the contrasting perspectives of the mass of annual events as the place of affectionate solidarity. Relations with supportive, affectionate women (mothers, sisters, wives)—absent from the symbolism of the public city—are emphasized. Other primary household festivals are occasions for worshiping mothers and fathers and the benign deities, loci of human ideals, affection, and identifications—Laksmi as guardian of the storeroom, Siva and his benign consort, Ganesa[*] , Visnu[*] , the Rsis[*] . In the movement of women among households, the household and its persons are related to a particular larger network of households, those of the "mother's brothers," of the women's tha: che(n) s, their "own homes." This network, as we have discussed in chapter 6, is a nexus of warm personal support when seen in contrast to the austere patriarchal network, the phuki , which must ensure proper lineage, thar , and civic behavior. When the household in this thematic mode of affectionate relationship spills beyond its boundaries, it is primarily into the neighborhood, the twa :, with its neighborhood Ganesa[*] shrine, which acts as a kind of fringe of family-like relationships around the household.

The household person lives in a sort of tube within the walls of the household, a tube that is open at both ends into time. One is born into the household from some previous incarnation—a vague idea that is not represented in the festivals. One will finally leave it to move on, keeping much of one's household self, into Yama's realm and to a pleasant rebirth or social heaven beyond. Death—ordinary death[14] within the household—is the threshold within this open-ended tube of personhood to a next moral stage, the stage where the person's morally earned soterial rewards or punishments will affect the conditions of his or her new life. Annual events comment on this threshold. They explore ways of holding on to household existence for as long as possible in the face of a humanized god of death, Yama, who honors his promises and whose messengers can be distracted and deceived. Household events also ensure the remembrance of the household's personal dead (not the distant unknown patrilineal "fathers" of the rites of passage) and, in conjunction with the public Saparu festival, ease their passage into Yama's realm. Thus the annual household events represent the career of the individual in his or her intimate personhood through a span of time encompassing both sides of death.

The household is a place of familiar refuge at the center of the systematic displacements an individual experiences in the course of the annual cycle. It is the here and now position within the "tube" of person-hood extending from distant past into the postmortem future. The annual events also explore the limits and the phases of the person in another direction, "laterally," through the walls of ordinary household personhood. They probe downward into the person's body, outward into the city, and beyond. The lunar new year begins on Mha Puja [1] with the worship of the "mha "—a word indicating both body and self—of each individual. In the course of its worship the mha 's elements, the mahabhuta , "of which the body is supposed to he composed and into which it is dissolved" (chap. 13), are represented. The body is given a meat-containing offering, and thus treated as if it were a meat-eating dangerous deity. This offering is not to the benign "indwelling god," usually thought of as Visnu[*] , who is or who inhabits an individual's soul, a soul habited somewhere in the body. This offering is to a deified something else, the supporting matrix that houses the soul, a matrix that exists everywhere beyond the bounds of the person and the household, and which represents everywhere in Bhaktapur's symbolism the threatening and sustaining amoral forces at the boundaries of the moral world.

Another move away from the household and household personhood, that from household to phuki , is little represented in annual festivals, although it is an aspect of all rites of passage and of all Tantric worship of upper-status lineage deities. There is a radical shift when an individual moves from household to phuki , as there is when he or she moves from the self to its bodily support. The move is from the affectionate moral order of household relations supported and represented by the benign deities to an order whose more burdensome morality is sternly enforced by means of the fear-inducing meanings, emotions, and practices associated with the dangerous deities and their sacrificial religion. Phuki worship makes use of symbolic resources similar to those used in urban festival integration, but in the annual cycle it is not represented so much as a nested unit of the city but as a kind of parallel to it. The locus of its main annual ceremony is not the Aga(n) House within the city, but the Digu God shrine beyond the city's boundaries. The phuki and the city are both in their own, different, ways at the perimeter of the household and share the same kinds of order-ensuring forces. It is in the rites of passage that the phuki 's force over the household is centrally emphasized, and in those rites the phuki 's relation to the orga-

nization of the larger city is also not particularly emphasized, but only sketched in movements to the mandalic[*]pithas .

Outside of the household people are reminded that the family-based moral order, the order of love and respect and of the forms of valid shame and guilt based on intimate family experience, is shared throughout the city where it is written large in support of king, Brahman and the social hierarchy as members of a great family. The festivals of the benign deities—primarily in the jatra processions along the main city festival route, the pradaksinapatha[*] , and secondarily in visit to temples of benign deities—display and honor these moral values. In this group of civic enactments the ordinary person of the houehold extends his or her imagery of the household to the larger city.

But this extension of household imagery is a minor move in Bhaktapur's festivals. For the most part the festivals in public space deal with something else, paralleling the shift in the move from household to phuki . The festivals which use dangerous deities to designate civic areas and their relations make use of forces and images different from those used by the household and its extensions. Here imagery and implications played down or hidden in the annual cycle's imagery of household and household person are brought forth, elaborated, shaped, distorted, and given a social placement in the representation of the fertile, dangerous, and enforcing borderlands of social order and personhood.

When people move still further out of the household, beyond the borders of the city, they encounter a new realm of a quite different kind. There are eight events ([3], [4], [7], [15], [33], [39], [46], and [51]) during the annual cycle where a shrine far outside of the city (as opposed to just outside of its borders) is the focus, sometimes for all who choose to go, or (in three cases) for those who have had a death in their family within some designated period of time. Women also may make pilgrimages to valley shrines during the period of the Swathani Vrata. The principal deities of these pilgrimage sites are, with one only apparent exception,[15] once again benign deities. These out-of-the-city events bring people from Bhaktapur into crowds of Nepalis and, sometimes, North Indians from many different ethnic groups. They are movements out of Bhaktapur's particular order into a larger, less differentiated humanity. In these far out-of-the-city activities, Bhaktapur is represented negatively, as it were, in leaving it. What is found "out there" is a larger community of fully human beings—albeit on vacation from various kinds of local social orders—in a context of references to

moral orders beyond Bhaktapur's civic order, the cosmic realms of Visnu[*] and Siva, their heavenly cities and the realms of the remembered and beloved dead. Similar in meaning to the melas , and associated, as several of the annual melts are, with the fate of the souls of Bhaktapur's recent dead, is the Saparu carnival.

Melas and carnival are thoroughly within the moral realm. Here, in a familiar anthropological phrasing (Victor Turner 1969), there is a movement toward a generalized human "communitas " that is substituted for local division and categories of social ordering. In Bhaktapur's example of carnival , a characteristic universal genre for an escape from ordinary civic order, the carnival associated with Saparu [48], some privileged men playfully divest themselves of their roles and take on other familiar roles. Presumably in the process of shedding one role and pretending another—including some nonhuman ones—they enjoy for a few hours the brotherly excitement of shared being and omnipotentiality rather than the restrained pleasures of the security of social order. However, this escape from structure in Bhaktapur remains for the most part carefully within the bounds of the deeper categories of social order. Men switch roles, but do not reject the reality of role itself, nor, for the most part, of familiar culturally designated roles. Even in the farthest reaches of communitas the social category of "humanity" and its varieties is still kept. As Turner (1969, 131f.) puts it, suggesting the horizon of communitas , but going far beyond what Bhaktapur's melas , carnival, and other annual moral antistructural moves achieve:

Essentially, communitas is a relationship between concrete, historical, idiosyncratic individuals. These individuals are not segmentalized into roles and statuses but confront one another rather in the manner of Martin Buber's "I and Thou." Along with this direct, immediate, and total confrontation of human identities, there tends to go a model of society as a homogeneous, unstructured communitas, whose boundaries are ideally conterminous with those of the human species.

Some of the pleasures of the Saparu carnival are quite different from the escape from society into an unsegmented pan-human I-Thouness. There is also a darker possibility seen in some few of its images—those of demons and powerful beasts—of a more radical escape, this time from human identity itself. "Communitas " versus "social-structural order" is a tension, as the quotation from Turner points out, within "the social," a tension between "models of society," of aspects of "human identities." The tension here is between two moral orders , a "social-structural" one and a "communal" one. This particular dichot-

omy of "structural" and "antistructural" within the human realm is contained and represented in Bhaktapur in the terms of individuals' relations to the moral deities and to morally ordered death. In myth its prototypical mediating figure is Siva, who is a marginal moral actor within the realm of the gods and who is easily duped into giving morally unmerited rewards, familiar from many traditional stories, rewards that are misused by the unworthy recipients. Thus, during Sila Ca:re [15] people mimic a legendary "accident" in which a preoccupied Siva was deceived into taking someone directly and totally undeservedly into his heaven. Playing with chance and luck in festival gambling [Swanti] and the use of deceits and manipulations that distract and delay Yama's death-announcing messengers during the same sequence are examples of other human practices rehearsed in the course of the annual cycle that allow people to get around the heavy moral pressures of Bhaktapur's structured world.

Turner's 1969 treatment of structure and antistructure has a second antistructural option besides communitas , the Hobbesian "war of all against all" (1969, 131). Bhaktapur's festivals and symbolic resources also explore another kind of opposition to "structure" than communitas , bringing a subsidiary theme of carnival—its demons and beasts—to the fore. This opposition places yet another world in opposition to the realm shared by both communitas and social structure; it opposes a meta-moral or amoral world to a moral one. This is the nonsocial world around the city and within the individual, a realm in which communitas is irrelevant as the very categories of community and human are themselves dissolved. For Bhaktapur, however, this realm is not Hobbes's antisocial world. Life for humans within Bhaktapur's amoral realms might indeed have been conceived as "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short"—or even worse, for the predatory dangers portrayed in Bhaktapur's civic environs are perhaps more ingeniously terrrible even than Hobbes's "nature." But Bhaktapur's antisocial realm is not the near chaos Hobbes feared if the then recently achieved balance between newly individualized citizens freed from a restraining medieval world view and the equally new nation-states were to be disturbed. The realm of the amoral in Bhaktapur—neither social-structural nor communitas —is extensively represented and encountered as consisting of underlying and environing forms and forces that have their own kind of mysterious, vital, often demonic order out of which the moral order draws its energies, whose forces the moral order depends on and uses to protect itself, against which it provides its own peculiar kind of order. This

balancing and restorative tension is clearly represented in the stories of the Devi Mahatmya and the festivals of the Devi cycle. The internal tension and oscillations between the benign (moral) and dangerous (amoral) deities is at the service of a larger order, which in its moments of exact balance is congenial to gods and humans, if not to that larger order's enemies, the Asuras. When the moral order and its context are in proper balance, as they become periodically as the result of Devi's bloody victories against the Asuras, then, as the Devi Mahatmya puts it, "favorable winds began to blow; the sun shone with perfect brilliance, the sacred fire burnt in a tranquil manner; and the strange sounds that had filled the quarters of space also disappeared" (X, 27; Agrawala 1963, 127). As represented in the imagery of the annual cycle, Bhaktapur's moral world and amoral worlds together assure, ultimately, a higher ordering. The "Asuras" are vague notations for still another, more radical, antiorder set against this balanced system, notations for some Nibelungian revolution that would plunge both gods and humans into chaos for the alien purposes of some other class of beings. And even this is only chaos from the limited point of view of gods and men.[16]

The annual cycle of events systematically defines certain aspects of their city and their personhood to individuals, but it does not celebrate a unified "individuality."[17] In their relation to individuals, the different kinds of events in the cycle have to do with the different aspects of the person that are realized in the various arenas that are the concern of the annual cycle. The individual is portrayed as a dynamic and delicate interface, as constructed of constituent elements that can dissolve into something else, as shifting according to (and thus as being dependent on) his or her relation to different civic arenas, as located in, generated out of, and defended against the environing amoral worlds found outside of the various urban units and, in their internal relation to an individual's body and mind, beyond the inner boundaries of the individual's self.

In the course of the annual cycle individuals rehearse their membership in most of the nested units that define their complex citizenship in Bhaktapur—the cities beyond, the city itself, the city half, the mandalic[*] section, the twa :,[18] the phuki and the household family. For the most part they do this directly, not via representatives. The use of representative actors to indicate the hierarchy is exceptional. In the course of the annual cycle Bhaktapur moves each of its citizens into each of the

arenas that are the essential units and varieties of their social experience and of phases of their selves. Positioned successively in each arena, citizens find the appropriate forms of the city's symbolic world rotating around them, engaging them in contemplation and action.

Bhaktapur's other symbolic enactments, driven by other tempos than the annual cycle, have other centers than the city itself, and from the points of view of their participants are local and private affairs. They concern the cellular components of the city that the larger public order of the city presupposes and with which it must deal, components whose outputs are necessary for the order of the larger city.[19] It is the annual cycle that describes and, in part, makes the integrated civic order of city and citizen in which these smaller symbolic enactments find their place.