Gatha Muga: Ca:Re [45]

On the ca:re , the fourteenth day of the waning fortnight of Dillaga in July, a little less than five weeks after Bhagasti, the events of Gatha Muga: Ca:re (see fig. 28) bring the events of the intermediate period to a climax and to a close. By this day the transplanting of the plants that

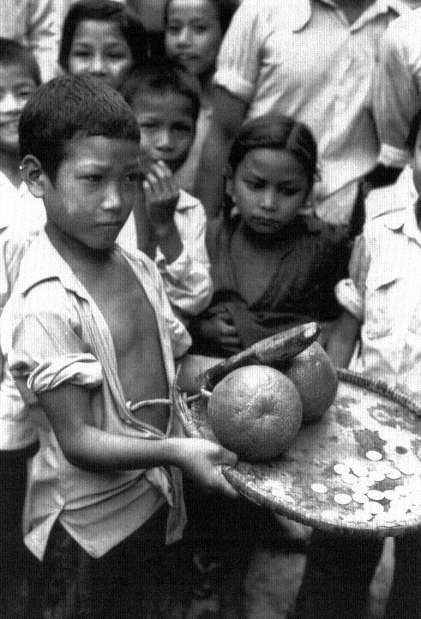

Figure 28.

The demon Gatha Muga:.

have been grown from the rice seed into the—if all has gone well—rain-flooded paddy fields has ideally been completed.[18]

Although the Nine Durgas themselves have departed, the Gathas whom they will possess again at Mohani continue their esoteric preparatory activities. On this day, according to some accounts, the Gathas take some black clay soil from the river bank and make a linga[*] representing Siva from it. Some of this soil will later be added to the new Nine Durgas' masks to be made by the mask maker before the reappearance of the Nine Durgas during Mohani (Teilhet 1978, 86).[19]

The main public activities of this day are related to the expulsion of the dangerous spirits, vaguely characterized as "bhut-pret " (chap. 8), which are conceived to have accumulated in the city and paddy fields at this time, and which can now be chased out of the city and fields and destroyed. The expulsion of the spirits—represented by a particular dangerous being, Gatha Muga:—comes at the time in the cycle when the complex events of nature necessary for the rice cycle have usually allowed for the firm establishment of the rice plants in the irrigated fields. Now some of the disorder associated with relinquishing control to the dangerous generative forces of the outside can be overcome in the humanly orchestrated expulsion of the demons and in the consequent cessation of the obscenity that mimics those generative and disorderly forces. There will continue to be risk from the weather until the rice harvest is completed, however, and a season of sometimes devastating gastrointestinal diseases is now at its height. In the language of the Devi cycle, the city still lacks the protection of the Nine Durgas. It will not be until Mohani and their reappearance—at the tension-reducing time of the rice harvest itself—that the danger will be once more fully under control. On this day, Gatha Muga: Ca:re, most households drive iron nails into the main doorway of their houses to protect them from bhut-prets , and some people put on iron finger rings[20] and keep them on for days to protect their bodies.

The central imagery and legendary references of the day have to do with the giant demonic figure, Gatha Muga:, whose appearance and story overlap with that of a South Asian Raksasa[*] , a giant fairy tale type of ogre, named Ghantakarna. Gatha Muga:[21] was a dangerous predatory being variously described in different accounts. According to Anderson, "he was so corrupt that he vilified the gods themselves, defiled and destroyed homes and fields, roaming the land, stealing children, maiming the weak, killing and devouring his captives. His

depraved sexual orgies and unspeakable excesses with his countless wives horrified the pious people" (1971, 72).[22]

There are, in addition, more human accounts of Gatha Muga: in Bhaktapur, which suggest its Newar urban complexity. In a story widely known in Bhaktapur, "Gatha Muga: was a man who believed in karma , and not in the power of the gods."[23] The story continues, "he loved the poor people. He sat at the crossroads where he took money from the rich to give to the poor.[24] If rich people refused to give money to him for this purpose, he would kill them. He also lived without concern about pollution. As he lay dying he hung bells on his ears, so as not to hear the gods' names called out.[25] After his death [because of his failure to conform to traditional religion] no one was willing to cremate him, and his body was left at a crossroads. But then [ordinary] people joined together to donate money for his cremation, and they called a low caste man to perform it. Many people followed this procession because he had always protected the ordinary people." This legend throws an oblique light on a number of tensions, contradictions, and paradoxes in Bhaktapur's systems of moral control. For our present purposes, however, the story refers to aspects of the actions of the day, and illustrates an ambivalence, an attraction and repulsion, in what is symbolized by Gatha Muga:.

The events of the Gatha Muga: day, as well as the salient legends, differ somewhat in different Newar communities.[26] In Bhaktapur each neighborhood area constructs representations for Gatha Muga:, interpreted in the neighborhoods as demons who once inhabited the local area. These vary in size, complexity, and elegance from vaguely anthropomorphic bundles of straw to elaborately masked, painted, and dressed figures (see fig. 28). The more elaborate figures have faces with fangs and often with bells at their ears, in reflection of the legends. Most of these figures are larger than life size; some have legs and will be carried, others are hollow papier-mâché constructed over wicker frames that are placed over a man who dances the demon. Some of these figures when carried or worn reach a height of eight or nine feet. Some are given crowns, mustaches, and beards, military jackets with epaulets, and rows of medals. This adds the imagery of a recent (in Bhaktapur's perspective) and alien authority to the demon's complex meanings. Whatever the variations in the figures, all are equipped with very prominent phalluses, often some two feet in length, and a pair of large globular fruits representing testicles. Sometimes red powder and strings of red beads are placed at the end of the phallus to represent ejaculated sperm.

In each neighborhood bundles of wheat straw are prepared which will later be used as torches in the processions chasing the demons, represented by the Gatha Muga:s, out of the city and, finally, for fire for their cremations. Throughout the city groups of small boys block various roads, in an echo of the legend, and demand coins from passersby before they are allowed to proceed along the road (see fig. 29). In the late afternoon and evening music is played in various neighborhoods, often by Jyapu music groups, and the giant figures are made to dance. Finally the time comes when the bhut-prets are to be expelled from the city. Processions form in each neighborhood and men and boys, holding torches in their hands, and shouting the sexual insults that they had been using since Bhagasti, chase the demons out of the city.[27] The processions are called bha kayegu , which refers to processions accompanied by shouting of conventionalized phrases, but this is a travesty of such processions in which the phrase is often "victory" or the like. The figures are taken beyond the boundaries of the city and set on fire. In contrast to other major processions very few women watch the procession from the roadside or other public areas. They go into their houses "to avoid being insulted" and watch through the windows.[28] After the cremation some people wash their faces and eyes in the river as a perfunctory purification. Then the members of the processions and the onlookers drift back to their homes. There are feasts in many households during the evening.

Gatha Muga: Ca:re culminates in a partial restoration of civic order. Obscenity, which had reached a crescendo on this day, will now cease. The Gatha Muga: figure in its form and legends combines in itself unsocialized sexual power, wanton destructiveness, and a mockery of authority. But all this is ambivalently viewed. He and his behavior are demonic and dangerous but fun, shameworthy and demonic but praiseworthy, rebellious against the gods and the rich but a support of "poor people" who love him in turn. He is driven from the city and his ashes returned to the bordering outside where the rice plants are growing and where the Nine Durgas had generatively gone to die and to sleep the month before.[29]

Not only does Gatha Muga: represent various kinds of threats to Bhaktapur's social and cultural structure in his legends; such antistructural emphases are reflected in the day's actions. The day dispenses with deities and with priests, and with references to any of the city's hierarchical roles. The only references to authority are the crowns and

Figure 29.

Gatha Muga: Ca:re. Children holding a phallic representation of

Gatha Muga: block the streets and demand money for passage.

the medals, and military mustaches of Gatha Muga: himself—and he is destroyed. The city is represented, not in the kind of integrative events characteristic of structuring festivals such as Biska:, but in the parallel activities of the neighborhoods. But these are only loosely coordinated. Each neighborhood constructs Gatha Muga: after its own fashion and follows its own funeral routes out of the city.

The disorder mimed here is not the same kind of social disorder referred to in Biska:. This disorder, like all the disorder of the Devi cycle, has a vitality about it that represents the unruly and generative life—both of individuals and of the environing world—that the moral order must depend on as well as control.

Now for two months, between Gatha Muga: Ca:re and Mohani, the climactic festival sequence of the Devi cycle, during the slow growth of the rice plants to maturity, there are no events in the Devi cycle. Agriculture is left now, so to speak, to its own unfolding. The ordinary lunar cycle, however, is crammed with events. There are twenty-one of them in the intervening sixty days (chap. 13).