PART ONE

ORIENTATIONS AND CONTEXTS

Chapter Two

Orientations

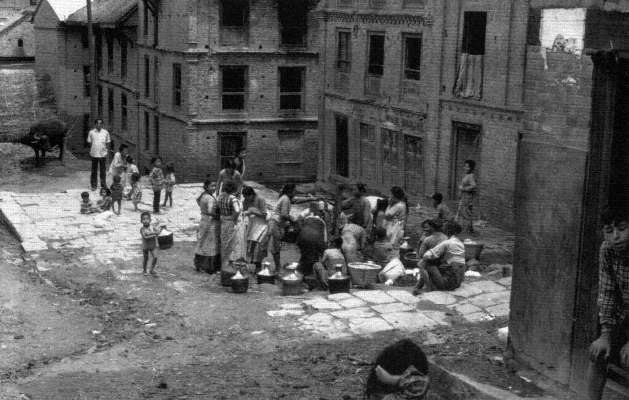

In the following chapters we will discuss those aspects of the past and present of the Newars and of Bhaktapur that will serve as context and background to our principal concerns. We must first introduce the Newars briefly and then, at rather greater length, present a collage of theoretical "conceits" that will suggest the field of discourse in which this book and its selections, arguments, and assertions is located.

Bhaktapur and the Newars

Traditional Nepal, an ancient Asian society with a literate high culture, was confined largely to the Kathmandu Valley. The people of this valley came in time to call their territory Nepal, themselves Newars, and their language Newari. Archaeology has not yet fully clarified their prehistory, but it seems that at an early period (perhaps the eighth or seventh century B.C. ) a predominantly Mongoloid, Tibeto-Burman speaking people settled in the valley where they may have encountered an aboriginal population speaking an Austro-Asiatic language. From perhaps the first or second century A.D. a political organization emerged that was to characterize the Kathmandu Valley until the late eighteenth century. A ruling class, a king and his court of North Indian origin, speaking and writing Sanskrit for sacramental and literary purposes and a Sanskritic North Indian language (a Prakrit) for everyday purposes, was progressively woven into an underlying society and culture with Hima-

layan and Central Asian features. Gradually a language (Newari) and culture (Newar) arose that synthesized these elements. Although the Sanskrit culture of the priests and court persisted, it became more narrowly traditional and ceremonial. Progressively more of the larger religious, political, and literary life was expressed in Newari and Newar forms.

There were dynastic disputes and confusion, but the Newars flourished. The valley soil is exceedingly rich, the bed of an ancient lake. A complex system of irrigation works for the collection and distribution of rainwater from the slopes of the surrounding hills was inaugurated sometime prior to the establishment of the first North Indian dynasty, and the rich soil and irrigation permitted highly productive farming. The Valley in time found itself on the major trade routes between India and Lhasa, in Tibet, and trade, tolls, and services became the basis, along with the rich agriculture, for considerable wealth. This made possible (and was, in turn, developed through) a great sociocultural efflorescence.

Stimulated by Indian ideas and images throughout a very long period of time, the Newars began, perhaps from the fourth century onward, the progressive elaboration and centralization of their society and culture in urban centers. Of these, three—Bhaktapur, Patan, and Kathmandu—became variously principal or secondary royal centers. They became concentrated, bounded (walled during certain times), highly organized units, surrounded by a hinterland of farmland and villages. Finally the three cities became politically divided. The hinterlands became territories, and three small states developed, each with its own central royal city, its king, its particular customs, its dialect.

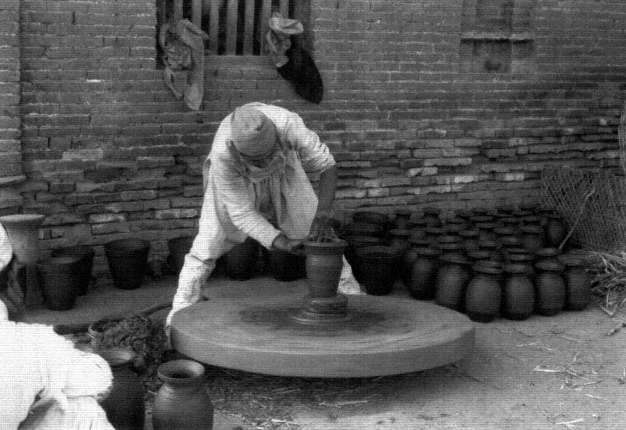

During these centuries the Newars created architecture; sculpture in wood, stone, and metal; music; drama; a multitude of beautiful crafts; and domestic goods—and above all they created a complex public religious and social drama, for which the cities became the great stages. In these Kathmandu Valley cities there was an elaboration of a particular kind of society, culture, and person. This had much to do with Hinduism (in its widest sense as a set of peculiarly South Asian understandings, images, and actions) and much to do with the structural necessities and implications of a certain kind of organized life, which I shall call here the "archaic city."

In the late eighteenth century the Newar kingdoms, divided and inward-looking, fell to the attacks of the armies of the chief of the small Indianized mountain state of Gorkha in the western Himalayas. The Gorkhali alliances and conquests defined the greatly enlarged territory

and state of modern Nepal. The Newars were no longer the people of Nepal. They were only one of some seventy linguistic and "ethnic groups," and a conquered one at that. The Gorkha alliance put its capital at Kathmandu, and the long autonomous political history of the Newars was over.

Yet, Bhaktapur, only eight often muddy miles away from Kathmandu (a long enough distance for those who walked or were carried in palanquins) was left more or less alone. It lost its Newar king (although he continued and continues to be powerfully present symbolically) but it remained relatively isolated by Gorkhali political policy for dealing with what was in effect a conquered state. That policy, variously motivated, was to isolate Nepal from the "outside," and to isolate Newars from power within the new state. The Gorkhalis encouraged Newar traditional life, as had the previous North Indian founders of Newar dynasties. However, these latter-day rulers did not become integrated as their predecessors had into a Newar state. The conquerors' language, Gorkhali, became "Nepali," the official language of the newly expanded country, and the Newars found themselves no longer a small nation, but in the eyes of other Nepalis (although not in their own) just one "ethnic group" among others.

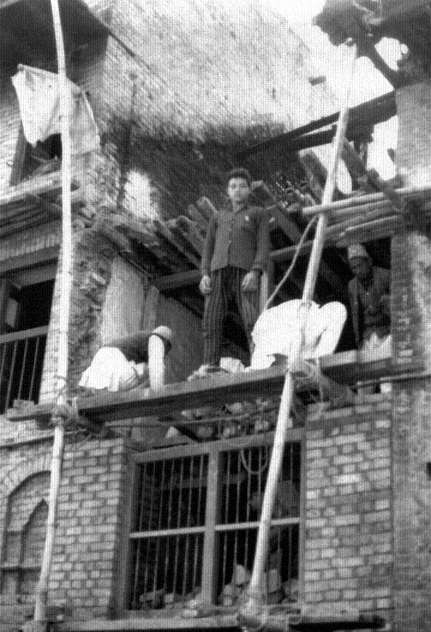

Bhaktapur ran on in very much the old way, like a clockwork mechanism assembled long ago that no one had bothered to disassemble. The first serious shocks of modernity began only in the early 1950s, when, following a political revolution, Nepal opened itself to the West. Development—education; agriculture; health programs; increasing travel in and out of the country; burgeoning communications of all kinds, books, movies, radio; and internal transportation—began to alter this conservative, isolated Himalayan country.

Altered in what way? Bhaktapur had always been m history, but it had tried for hundreds of years to turn the flow of history into what might seem a timeless eternal civic order. In 1973, when this study began, the city, or most of it, was still trying. The signs of a deep transformation to another way of being in time and in history were evident and were illuminating for both what had been and what might be about to happen. This book is concerned with the struggle to order Bhaktapur, its particular way of carving out a space and time and common reality in the face of history. It describes at length things that are important in that they are aspects of that order. As the order changes, as it "modernizes," such things will be of interest for other reasons—as problems for modernization and as potsherds left over from old broken pots, clues for antiquarian enterprises.

Ways of Looking at the Organization of Bhaktapur

Ballet

We will make use of some interrelated ways of looking at and talking about Bhaktapur. The book will illustrate the value these "fanciful and ingenious conceptions" or "conceits," as they once could have aptly been called, may or may not have. Our collage of conceits is more fanciful, literary, and metaphorical than precise, but "marked symbolism," "ancient" and "archaic" types of cities, "axial transformations," "epistemological crises," and the like are ways of adumbrating what seem to us the important tendencies and relations that may well be lost in the mass of details that are to follow.

We may start with an assertion that in comparison with certain kinds of simple traditional communities such as Tahitian villages[1] on the one hand, and with complex modern urban communities on the other, Bhaktapur is to a very large degree characterized by the presence of a great deal of a certain kind of symbolism. We may defer for a while the questions as to what kind of symbolism and what that symbolism might do, what purposes it may serve. For now we may characterize it as "extraordinary," and of compelling local intellectual and emotional interest. That symbolism is, in large part, derived from the vast resources of South Asian "religious"[2] ideas and images, locally transformed, ordered, and put to use for Bhaktapur's civic purposes.

In the following chapters after first considering the contexts of Bhaktapur's "symbolic world," we will distinguish and discuss various aspects and elements of that world. For those who live in or are familiar with other kinds of cities, whose experience of urban symbols is of a different kind, it may be useful to think, at the start, of the civic life of Bhaktapur as something like a choreographed ballet. The city space is the carefully marked stage. Beyond the city is another sort of space, another kind of world, the wings of the civic stage. Both the civic stage and its wings are symbolically represented, the dance moves off center stage at times, but the symbols, conceptions, and emotions proper to the city stage and to its wings are quite different, although interdependent. The civic stage is separated from the "outside" by clear boundaries and is elaborately differentiated and marked out through the symbolic divisions imposed on the physical space of the city, which we will present in chapter 7. These spaces contribute their own meanings to the

performances that take place on them and, in turn, take further meaning from these performances.

Distributed through this differentiated space are images of deities, shrines, and temples, many of which are semantically appropriate to the spaces they characterize. Like all our analytically separated out aspects and elements, specific deities give meaning to and take meaning from the other aspects—space, actors, time, form of enactments, and so on. We can think of the gods and shrines as the distributed, differentiated, and, above all, meaningful decor of the ballet, setting the mood and context against which the human actors dance. "Decor" is too weak for the deities' roles, however; they strain our metaphor, and their contribution is more like that of the Commandatore in Mozart's Don Giovanni , part decor, part singer. We introduce them in chapter 8.

Largely through descent, roles in this ballet are assigned to the city's inhabitants. There are more than 300 clan-like units (thars ) that in large part determine what ritual and occupational roles their members will play in the city. These are ranked in some twenty or so "macrostatus levels," in a hierarchy of statuses from king and Brahman to untouchable. Civic roles, the civic social structure, is the subject of chapters 5 and 6.

Actors, decor, and space are set into motion by the city's conventional arrangements of time, the music of the ballet, signaling various beginnings and endings, rhythms and tempos, entrances and exits, movements, and phases of performances. There are some eighty annual events[3] determined by the lunar and solar calendars. There are other times and tempos in the city. The time of the life cycle—birth, maturation, menstruation, and so on—brings on stage a dozen events during life, and a large number on dying and after death (app. 6). Another kind of time, making use of the planets and, for some purposes, the moment of birth, is associated with its own deities, the astral deities (chap. 8) and is used in attempts to bring the city dance into relation with what seems from the perspective of the order of the dance to be choice, accident, chance, and luck.

If one knows what a person's surname is (the designator of his or her thar ), his or her age and sex, what day of the lunar (for some purposes the solar) year it is, and where the person lives in Bhaktapur, one can make a plausible guess at where he or she is, what he or she is doing, and even something of what he or she is experiencing. One has come to understand "the work." This is, in part, simply to claim that there is considerable social and cultural order in Bhaktapur. This in itself is

banal, but when that order is placed in comparative perspective, when the details of the ballet are worked out, when the relations between actor and role, between person and symbol are considered—then the question shifts from order to a special order, and, in part, a particular kind of order. Our approaches to "kind," our typological conceits include "the archaic city" and "climax Hinduism."

Typological Conceits: The Archaic City

Bhaktapur, as we will see in chapter 4, is an exceedingly densely populated community containing a very large number of people (in the comparative scale of premodern communities), whose life in relation to that community is highly and complexly integrated. Their community life is such—to paraphrase a synthesizing definition of the "city" in archaelogical perspective (Redman 1978, 216)—that their identity derives from their aggregation, an aggregation that is formally and impersonally organized, that the economy of the community comprises many nonagricultural activities and provides "a diversity of central services both for its inhabitants and for the smaller communities in the surrounding area."[4] This makes Bhaktapur a "city" by such criteria, but what kind of city?

In a fundamental paper on "the part played by cities in the development, decline, or transformation of culture," Robert Redfield and Milton Singer (1954) attempted a classification of types of city in historical perspective. For our purposes their types can be divided into two different sets. The first is a group of types in which cultural heterogeneity and secularity are of central importance. These are cities, in their words, where (Redfield and Singer 1954, 57):

one or both of the following things are true: (1) the prevailing relationships of people and the prevailing common understandings have to do with the technical not the moral order, with administrative regulation, business and technical convenience; (2) these cities are populated by people of diverse cultural origins removed from the indigenous seats of their cultures. They are cities in which new states of mind, following from these characteristics, are developed and become prominent. The new states of mind are indifferent to or inconsistent with, or supersede or overcome, states of mind associated with local cultures and ancient civilization. The intellectuals of these . . . cities, if any, are intelligentsia rather than literati.[5]

In contrast, there are kinds of cities that they term "administrative-cultural" "which carry forward, develop, elaborate a long-established

local culture or civilization. These are cities that convert the folk culture into its civilized dimension" (ibid., 57). These are the cities of the literati. They also call this kind of city "the city of orthogenetic transformation," and "the city of the moral order," in contrast to the "city of heterogenetic transformation and technical order." They claim that the first cities in early civilizations were cities of orthogenetic transformation where local culture was carried forward rather than broken down to be replaced by new means of relation and integration, familiar to us in Western urban history.

In an analysis of such early cities, Paul Wheatley (1971, 225f.) argued for the centrality of "symbolism" in their structure and function:

Whenever, in any of the seven regions of primary urban generation, we trace back the characteristic urban form m its beginnings we arrive not at a settlement that is dominated by commercial relations, a primordial market, or at one that is focused on a citadel, an archetypical fortress, but rather at a ceremonial complex. . . . The predominantly religious focus to the schedule of social activities associated with them leaves no room to doubt that we are dealing primarily with centers of ritual and ceremonial. Naturally this does not imply that the ceremonial centers did not exercise secular functions as well, but rather that these were subsumed into an all-pervading religious context. . . . Operationally [these centers] were instruments for the creation of political, social, economic, and sacred space, at the same time as they were symbols of cosmic, social, and moral order. Under the religious authority of organized priesthoods and divine monarchs, they elaborated the redistributive aspects of the economy to a position of institutionalized regional dominance, functioned as nodes m a web of administered . . . trade, served as foci of craft specialization, and promoted the development of the exact and predictive sciences.

Bhaktapur is not an ancient city in terms of historical continuity, but its organization reflects many of the same principles that have been ascribed to otherwise differing ancient cities as members of a certain type of urban community. As a member in some respects of such a class it may well suggest, mutatis mutandis , something of what they might have been, and may be thought of as an archaic city.

Historical Conceits: The Ancient Indo-European City and the Axial Age

In his classic, once influential, and recently much criticized[6] 1864 study La Cité Antique , Fustel de Coulanges was (of interest for our present

purposes) concerned with a transformation from one state of affairs to another, the transition to the classic cities of Greece and Rome. This work, and its echo in the idea of a transformative "axial age," give us another set of metaphors to suggest Bhaktapur's peculiarities. Fustel tried to look back through the texts of "the Greeks of the age of Pericles and the Romans of Cicero's time" for clues to an earlier urban organization of society and religion that was already ancient to Classic Greece and Rome, clues preserved in vestiges of language and ritual and legend. He added, because of his "addiction to the newfangled Aryan doctrine" (as Finley [1977] puts it) comments on what he took to be early Indian social forms based on his reading of available translations of some Sanskrit texts. He felt that the first Mediterranean European cities arose on the basis of a shared peculiarly Indo-European family organization. "If we compare," he wrote, "the political institutions of Aryas of the East with those of the Aryas of the West, we find hardly any analogy between them. If, on the contrary, we compare the domestic institutions of these various nations, we perceive that the family was constituted upon the same principles in Greece and in India" (Fustel de Coulanges 1956, 113).

According to Fustel's idealized schema the preclassical ancient city was built out of successively inclusive cellular (bounded and internally autonomous) units (ibid., 127f.).

When the different groups became thus associated, none of them lost its individuality, or its indpendence. Although several families were knitted in a phratry, each one of them remained constituted just as it had been when separate. Nothing was changed in it, neither worship nor priesthood, nor property nor internal justice. The city was a confederation. . . . It had nothing to do m the interior of a family; it was not the judge of what passed there; it left to the father the right and duty of judging his wife, his son and his client.

There was a nesting of these cellular units—"family, phratry, tribe, city"—each level marked by its relevant gods and rituals, and in contrast to, say, a Frenchman, "who at the moment of his birth belongs at once to a family, a commune, a department and a country," (ibid., 128) the citizen of the ancient city moved via a series of rites de passage over many years into membership in successively more inclusive units.

Each increasingly inclusive level of structure (as expressed in Fustel's historical and temporal language) had its proper gods and cult. "In the beginning the family lived isolated, and man knew only the domestic gods. . . . Above the family was formed the phratry with its god. . . .

Then came the tribe, and the god of the tribe. . . . Finally came the city, and men conceived a god whose providence embraced this entire city . . . a hierarchy of creeds and a hierarchy of association. The religious idea was, among the ancients, the inspiring breath and organizer of society" (ibid., 132).

Each unit had its interior and its exterior, and the interior was protected by secrecy. Above all, this was true of the household. "The sacred fire . . . had nothing in common with the fire of a neighoring family, which was another providence. Every fire protected its own and repulsed the stranger. . . . The worship was not public. All the ceremonies, on the contrary, were kept strictly secret. Performed in the midst of the family alone, they were concealed from every stranger. . . . All these gods, the sacred fire, the Lares, and the Manes, were called the consecrated gods, or gods of the interior. To all the acts of this religion secrecy was necessary" (ibid., 37).

The ultimate unit to which people were related at this "stage" was the ancient city itself. There was "a profound gulf which always separated two cities. However near they might be to each other, they always formed two completely separate societies. Between them there was much more than the distance which separates two cities today, much more than the frontier which separates two states; their gods were not the same, or their ceremonies, or their prayers. The worship of one city was forbidden to men of a neighboring city. The belief was, that the gods of one city rejected the homage and prayers of any one who was not their own citizen" (ibid., 201).

What anchored and tied together this structure of cells was its rootedness in a fixed and local space. "When they establish the hearth, it is with the thought and hope that it will always remain in the same spot. The god is installed there not for a day, not for the life of one man merely, but for as long a time as this family shall endure, and there remains any one to support the fire by sacrifices" (ibid., 61). The city came to define in itself its own proper social unit and was sacred for that group within the city boundaries. Just outside the city boundary lived a special class of people, a special class of outsiders, who were placed in an essential contrast with the insiders. Those people who were "excluded from family and from the [family] worship fell into the class of men without a sacred fire—that is to say, became plebeians" (ibid., 231).

Fustel's portrait contained a deeply felt myth, that of an earthly paradise of orderly, family-based unities prior to a transformation into a

larger, impersonal, and conflict-ridden state organization. This was one of a set of such myths putting a lost or distant world into contrast with the modern. It was compelling to his contemporaries and annoying to those of ours who are engaged in countermyths. The problem for a summary rejection of Fustel's vision is that the particular formal features of his "Ancient City," that we have chosen to review here are characteristic of Bhaktapur.

Let us now consider another conceit that, in fact, supplementary to Fustel's has more respectability, or at least currency. For Fustel the features he imagined to characterize the primitive stages of the Indo-European "ancient city," disappeared in the Mediterranean West in those transformations of the ancient city that had made the Athens and Rome of Fustel's classic sources into new kinds of places. That sense of an historical transformation of High Cultures, somehow fundamental for what we are now, has been characterized in various ways. It has been seen as a watershed separating us from an alien, archaic civilized world, stranger to us in many ways than the world of primitive peoples. For Robert Redfield the transformation represented the breakdown of the moral order that had arisen through the "orthogenetic transformation" of a still prior cultural order, the "primitive world" (Redfield 1953). A new kind of basis for urban order was required, and the city and its inhabitants begin to be transformed into their modern forms.

It has been argued (for example, Benjamin Schwartz [1975, 1], in a volume reporting a symposium on "wisdom, revelation, and doubt: perspectives on the First Millennium B.C. ") that the European urban and cultural transformations were part of a worldwide wave of "breakthroughs" within the orbit of the "higher civilizations," during the first 700 or 800 years before the Christian Era in an "axial age" (the term and idea were suggested by Karl Jaspers) consisting in the "transcendence" of the limiting definitions and controls of these ancient forms. In Greece this was manifest in "the evolution from Homer and Hesiod to pre-Socratic and classical philosophy" (and, Fustel would have argued, in the changes in urban organization he discerned). For India, the "transcendence" might be seen in "the transition from the Vedas to the Upanishads, Buddhism, Jainism and other heterodox sects" (Schwartz 1975, 1).

When this argument is pushed beyond its heuristic uses toward more specific historical analysis and toward such questions—of interest to us here—as "did India undergo an axial transition" it becomes diffusely

problematic. In the same symposium Eric Weil notes that those who did not participate in this transformation have simply been rejected as ancestors of the modern world. In a consideration of the political and sociological conditions necessary for the nascent "transcendent" ideas to succeed , he notes in passing that the lack of a politically unifying force might explain "why historical and anthropological differences were never overcome in India. There is a tendency to forget these differences in order to bring India into our own scheme of historic progress toward universality; we wish to look only at those phenomena which fit" (Weil 1975, 27). The heterodoxies that followed the preaxial Vedas—particularly the one that proved elsewhere most powerful, Buddhism, with its powerfully transcending attack on the symbolically constituted social order that were concomitant with its ontological challenges—did not prevail[7] in India. What did prevail was ultimately the static social order of Hinduism, which, whatever its peripheral inclusion in their proper place of the socially transcendent gestures of renunciation and mysticism, was hardly any kind of "breakthrough" into whatever the idea of an axial "transformation" was meant to honor.

All of which is to suggest that traditional India and Bhaktapur, in so far as it may be characteristic of traditional India, are very old-fashioned places, indeed.

Typological Conceits: Kinds Of Minds—A Continent in the Great Divide

The quest for the defining "other" led in the nineteenth century to conceptions of powerful oppositions in contrast to European urban society. These oppositions, which left little place for "preaxial" civilizations, were dichotomies of two variously characterized extreme terms: simple, complex; primitive, modern; prerational, scientific; and Eden, Exile. The oppositions implied not only types of community organization but also aspects of the experience and thought of members of such communities, the "states of mind" of Redfield and Singer. "Gesellschaft ," for example, required of its members (in presumed contrast with "Gemeinschaft ")—as a consequence of its emphasis on contract and rationality in regard to an individual's "interests"—that "beliefs must submit to such critical, objective, and universalistic standards as [those] employed in logic, mathematics and science in general" (Loomis 1964, 286).

These dichotomies, like our various historical conceits, although they never fully characterized actual communities, have continued to haunt scholarly imagination as "ideal types" as possible tools in the quest for a clarification of aspects of social order. Paul Wheatley, in his discussion of the beginning of urban forms, uses the classical terms of contrasts. "We are seeking to identify those core elements in society which were concerned in the transformation variously categorized as from Status to Contract, from Societas to Civitas , from Gemeinschaft to Gesellschaft , from mechanical to organic solidarity, or from Concordia to Justitia " (1971, 167). In a footnote bearing directly on our view of Bhaktapur he added an amplification, the suggestion that the early city was of neither one nor the other type. "It should be noted that this transformation was only initiated by the rise of the ceremonial center and that . . . the society of the temple-city was neither fully contractus, civitatis, Gesellschaft nor organic" (ibid., 349 [emphasis added]).

The social philosopher Ernest Gellner is one of those who makes use of the dichotomy in a very strong form. Modern industrial civilization is unique and stands historically across a great frontier or divide from what went before. It is in "a totally new situation." The clarifying task is to characterize "primitive thought" in its oppositional contrast to the most powerful form of modern cognition, science. This contrast will help clarify how we are unique.

If this contrast is used as a method, then (Gellner 1974, 149f. [emphasis added]):

One is naturally left with a large residual region between them, covering the extensive areas of thought and civilization which are neither tribal-primitive nor scientific-industrial. Hence there is a certain tendency for evolutionary schemata of the development of human society or thinking to end up with a three-stage pattern. This tendency is a consequence of the fact that the very distinctively scientific and the very distinctively primitive are relatively narrow areas, and three is a very big region in between.

Nevertheless, it is my impression that the problem of the delimitation of science, and the problem of the characterization of primitive mentality, are one and the same problem. To say this is not to deny that the area between them is enormous, and comprises the larger part of human life and experience. But this middle area perhaps does not exemplify any distinctive and important principle . With regard to the basic strategic alternatives available to human thought, there is only one question and one big divide. . . . The central question of anthropology (the characterization of the savage mind) and the central question of modern philosophy (the characterization or delimitation of science) are in this sense but the obverse of each other.

It is the burden of this book that within this heterogeneous range of thinkers and thought between "primitive" and "scientific," and in the wide range of communities between the "simple" face-to-face community and whatever it is we have (or had) become, there is a kind of continent in the Great Divide, which has its own distinctive typological features, exemplifies its own distinctive and important principles in relation to both sociocultural organization and to thought, distinctive features that are blurred and lost in these classical oppositions. Bhaktapur and places that might have been analogous to it in the ancient world are illuminating for this middle terrain. Neither primitive nor modern, Bhaktapur has its own exemplary features of organization and of mind.

Organizational Conceits: The Civic Function of Symbolism in Bhaktapur and, Presumably, in Other Such Archaic Cities

Shortly after arriving in Bhaktapur, I (the senior author) was standing with a Newar inhabitant of that city in a public square when a nearby man began to shout angrily at a boy. "Who are those people," I asked, "and why is the man shouting?" My friend was unable to answer either question. In Piri, the Tahitian village, the understanding of, response to, and staging of such episodes was the predominant way in which village order was known, taught, learned, rehearsed, experimentally violated, and repeatedly brought under control. Conversely, worry that one's behavior would inevitably be seen and known to others—who would always know exactly who you were and what you were doing—underlay the moral anxieties central to villagers' discourse about and attempts at self-control. In its intimacy, in the constant interplay of being watched by the whole village and watching it, through its close agreement on moral definitions and proper responses, and above all in its construction of people's sense of a "normal" reality, the village of Piri operated as what Erving Goffman (1956) once called a "total institution" with consequent implications for the "mind and experience" of its inhabitants (Levy 1973). In Bhaktapur the kind of communally shared learning from patterned, contextualized, "ordinary" events which was pervasive in Piri was limited to only certain sectors of people's experience of the community—to the bounded and isolated household unit and, sometimes, to the larger kin group or the household's immediate neighborhood. Thus, how did the inhabitants of Bhaktapur understand, learn from, and adjust themselves to the larger city, most of which was out of sight and hearing, and whose complexity, whose quantities and

varieties of people and events seemed beyond any direct and intimate grasp? How did citizens understand and how were they affected by a city that, like Redfield's "cities of orthogenetic transformation," seemed to embody a cultural tradition in urban rather than village form? In large part, we propose, by making use of a resource for communication, instruction, understanding, and control that is not much used in Polynesian communities where culturally shaped common sense used to interpret culturally shaped face-to-face interactions and observations provides the core of community integration. Bhaktapur, in contrast, makes elaborate use of particular sorts of symbols—"marked symbols"—to solve the problems of communication induced by magnification of scale. How it does it, the extent and limits of the resource, is one of the concerns of this book.

Organizational Conceits: Embedded And Marked Symbolism

The idea of "symbolism" in anthropological studies has become so extended that it is little more than an invitation to view anything in the life of a community in a certain way. A symbol in this view is "any structure of signification in which a direct, primary meaning designates, in addition, another meaning which is indirect, secondary and figurative, and which can be apprehended only through the first" (Ricoeur 1980, 245), in short, in one or another context, potentially everything.

It is useful for comparative purposes—and particularly for emphasizing an important difference between places such as Piri and places such as Bhaktapur—to distinguish two different kinds or aspects of symbol or symbolism, "embedded" and "marked." The term "embedded" implies "indirect, secondary, and figurative meanings" that are condensed and dissolved in any culturally perceived object or event so that they seem to belong to the object or event as aspects or dimensions of its "natural" meaning. Examples of such culturally shaped embedded and naturalized symbolic forms are the Hindu and Bhaktapurian complex of purity, impurity, contamination, purification, and the like, which are the subject of chapter 11. "Embedded symbolism" is associated with the cultural structuring of "common sense," the structuring of the assumptions, categorizations, and phrasings through which processes of cognition themselves are structured and through which meaning is created and selected out of the flow of stimuli generated and experienced within a community. Such culturally constructed perceptions and understanding have the experiential characteristics of "ordinary

reality." They are no more (or less) questionable than any other sensations or perceptions, and the knowledge associated with them is felt to be directly derived from sensations and perceptions. Beliefs derived from or composing such knowledge are generally directly held with no epistemological problems. Faith is not at issue.

The "symbolism" of concern to recent "symbolic anthropology" has been, to considerable degree, such "embedded" symbolism.[8] However, the kind of symbolism that is strikingly elaborated in Bhaktapur is of the sort to which statements about "symbols" in ordinary discourse refer—something whose meaning must evidently be sought elsewhere than in what the object or event seems to mean "in itself." "Marked" symbols, in contrast to "embedded" symbols, are objects or events that use some device to call attention to themselves and to set themselves off as being extraordinary, as not belonging to—or as being something more than—the ordinary banal world. This is the symbolism of various attention-attracting, emotionally compelling kinds of human communication, whether it be art, drama, religion, magic, myth, legend, recounted dream, and so forth, which are marked in some way to call attention to themeselves as being special, as being other than ordinary reality. Most of this volume, beginning with chapter 7, is concerned with such marked symbolism and its special spaces, practitioners, messages, resources, and functions in the life of the city.

Typological Conceits: Hinduism As An Archaic Kind of Symbol System And Bhaktapur As A Hindu Climax Community

Bhaktapur, the argument goes, can be considered to have interesting typological analogies with archaic cities insofar as it represents a community elaborately organized on a spatial base through a system of marked symbolism. The particular symbolic system made use of is a variant of Hinduism. When contrasted with Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism (other than its Vajrayana and Tantric varieties),[9] Hinduism is a peculiar contemporary religion. Ahistorical (without a heroic, that is, transcending, founder, and without a future to be obtained through some progressive struggle of faith, wisdom, or rectitude); rooted in local space, a local population, and a local inheritance; distributive of its godhead into a pantheon of meaningful and immanent gods—essential resources for the organization of space, time, and community; insisting on the inclusion of social order and social behavior within the sacred realm; insisting on the presence of the sacred in

the here and now, and not restricted and banished to eschatological beginnings and endings and distant heavens—Hinduism is in many of its features, which contrast with the "world historical religions," a system for and of what we have called "archaic urban order."

Louis Dumont remarks, in a section of his study of Hindu caste treating "the territorial framework: the little kingdom," that "contemporary anthropological literature frequently stresses the fact that actual caste systems are—or rather, were—contained within a territorial setting of rather small scale. Here social anthropologists found what they were at the same time mistakenly seeking at the level of the village a social whole of limited extent, established within a definite territory, and self-sufficient" (Dumont 1980, 154). Dumont noted the periodic absorption of these "little kingdoms" into larger political states and argued that "the compartmentalization of the little kingdom must have been at its height at periods of instability and political disintegration" (ibid., 156). That instability and disintegration characterized the larger territory, but it was a stimulus to and opportunity for the ordering of the Hindu city-states—a royal city and its hinterland—within that territory.

Whatever the shifting historical relation between caste and territorial units might have been, the conditions that allowed for the formation and development of little kingdoms allowed for the fulfillment of Hinduism's potentials for ordering a community. Such little kingdoms seem to have represented, to borrow a term from ecology, "climax communities" of Hinduism, where it reached the full development of its potentials for systematic complexity, and with it a temporary stability, an illusion of being a middle world, a mesocosm , mediating between its citizens and the cosmos, a mesocosm out of time.

Psychological Conceits: What Is A Newar That He or She May Know Bhaktapur

Yeats put it exactly right in "Among School Children": O body swayed to music, O brightening glance, How can we know the dancer from the dance?[10]

Piri's dance and Bhaktapur's dance are greatly different. What about the dancers? The private lives of some of Bhaktapur's people, people whom we believe to be representative in some ways, will be the subject of another volume. There we will consider aspects of the city's traditional life, such as family religion and rites of passage, which are rel-

atively neglected here, as well as what some different sorts of people experience and how they interpret and are affected by the aspects of the civic life presented here. In this volume, as we remarked in the last chapter, we will deal with such personal dimensions at only a very few points where it seems necessary for suggesting the psychological impacts and functions of some of the city's most important symbolic patterns—this is the case, for example, with the discussion of purity and of aspects of the significance to the civic audience of the Nine Durgas troupe of god-possessed performers.

The differences in scale, complexity, and kinds of resources used for community organization have, we believe, direct implications for differences not only, obviously, in people's private experience but also (pace Gellner) for the "mentality" of people in the two communities. These private contrasts are both dependent on differences in community organization and help maintain and motivate them. For our final orienting conceit we will sketch some of these implications, asserting in a condensed, simplified, and idealized form what will be illustrated, argued, and qualified at length elsewhere. We must now look at our contrasting communities' organization once more, but this time not in itself but as it affects and is experienced by the communities' members.

As we have asserted above, much of the psychologically significant order of a traditional Tahitian village lies in its complex construction of what was locally taken to be literal reality, resulting in what William Blake, speaking of another world, called "mind-forged manacles." The heterogeneity of the village is contained within a narrow and relatively consistent set of assumptions, values, and definitions; this, as well as the structure and limits of vocabulary in certain domains, makes critical and philosophical thought and discourse difficult. This shaped experience, reinforced by hierarchies of coherent redundant controls (Levy 1977), results in convictions of the solidity and rightness of local common sense. Incompatible understandings, motives, and feelings are relegated to an unconscious realm, which is in large part derived from dense social agreement on the unthinkable. With the conscious aspects of their understanding constructed in a comparatively simple and direct manner out of the forms of the "total institution" in which they live, Tahitians act in its terms because it is the natural thing to do. An outsider sees the powerful influence of the village-based construction of local reality, but villagers acting from their certainties about the nature of their world, from their solidly constructed selves, feel themselves to

be very autonomous individuals for whom external controls or even advice on correct behavior from others in the village would be both unnecessary and oppressive.

What people know in what they take to be a trustworthy manner seems to them to be based largely on their sensory experience of their concrete world. They believe, for the most part, in what they think they see; in Tahiti, as is general in Polynesia, the word for knowing and seeing is significantly the same. The conditions of their life generate a corresponding epistemology. In contrast, if something with a claim to truth is presented to them through verbal reports or other obviously "symbolic" forms that seem disconnected or disconnectable from direct experience, they are suspicious, it is "only something that they have heard about." Even those claims of religion that are neither directly experienced nor intuitively "natural" are subjects for skepticism. Faith, a category that is essential for the Newars, is problematic for them. They are only dimly aware of differences in different people's subjective realities and have minimal interest in psychological or sociological speculation, the revolutionary viewpoints that enable a transcending insight into aspects of one's own possibly arbitrary reality and that make the very idea of "mind-forged manacles" possible. Living in their taken-for-granted common-sense reality, they are familiar to us as the kinds of people whom reflective intellectuals and sophisticated city dwellers see pejoratively as rural, provincial, naive, and unsophisticated people, rigid and unimaginative in their convictions and certainties and their dismissive encounters with other worlds.

Tahitian villagers live in a resolutely ordinary, daylight, sunny world. It is surrounded by a shadowy, poorly discriminated, and thus uncanny world, which they refer to metaphorically as the "night." They depart from the literalness of their daylight world into imaginative marked symbolic enactments, ceremonies, and rituals only on restricted occasions. Now and (as suggested in reports of the time of first Western contacts) in the past, symbolic enactments are and were used, as they are everywhere, mainly for signaling radical and usually irreversible changes of status, as digital markers of socially significant change of state—for the individual during rites of passage, and for the community for a transition from peace to war or the submission to a new chief. In these cases, where one socially defined object or person or situation is suddenly transformed into another, Tom suddenly becoming Harry, the pattern of the ordinary is not sufficient and something more than common sense is required.

The experience—and the personal consequences of that experience—of citizens of Bhaktapur is different. Like Tahitian villages, Bhaktapur is a bounded, largely self-sufficient, and highly integrated sociocultural system. But in Bhaktapur's complex organization every mature individual is involved in a great number of different culturally defined and validated realities and experiences calling upon and evoking quite different aspects of or even kinds of "self" as he or she moves from one to another.[11] Experience in Bhaktapur is greatly more complex; multiple points of view are not only possible but forced on people. Living systematically in shifting and contrasting worlds, many citizens of Bhaktapur are forced into an epistemological crisis, forced to the understanding that external reality, as well as self, is constructed, and in some sense illusory, or in the Hindu philosophical expression, maya .[12] They are now, like Princess Myagky in our introductory epigraph, in position for a kind of skeptical and critical analysis that transcends the ideology of their culture, and they become the anthropologist's potential collaborators in the analysis of their own culture and situation, rather than, as in the case of rural village Tahitians, the passive subjects of analysis.

Able in certain special contexts and conditions to say and know such things as "gods are representations of human feelings and activities," or "we must have untouchables because without them we would lose the caste system and there would be chaos," or "it is not the behavior of others so much as people's images of themselves that makes them accept their positions [in the caste system]," or "there must be shame and embarrassment everywhere in the world, but of course, what people are ashamed and embarrassed about must vary," people, quite ordinary people, in Bhaktapur's society are "sophisticated," in its dictionary sense of "altered by education, worldly experience, etc. . . . from the natural character or simplicity." If sophistication, taken as the index and result of a profound difference from the conditions that nurtured Tahitian life and mind, characterizes the majority (as we have reason to believe)[13] of the people of Bhaktapur, there is a still further move, a characteristic response to the epistemological shift that makes knowledge problematic that, in turn, distinguishes the citizens of Bhaktapur from representative (or ideal) moderns. For Bhaktapur is precisely as Redfield and Singer characterized the genre, a city of literati (that is, enthusiasts and technicians of marked symbolism) and not of intelligentsia. The insights that the preceding quotations illustrate are generated by minds working over contradictions and contrasts in the cul-

turally proffered certitudes of various sectors and phases of a complex culture, contradictions and contrasts that are potentially subversive to the society and in many ways problematic to the integration of the self. Rather than making the analytic pursuit of these intellectual problems an end in itself, a move that would encourage the formation of a social class of critical intellectuals, of socially destabilizing philosophers and scientists, people seek their most satisfying answers to intellectual paradoxes, mysteries, and threats to solid constructions of "self" and "other" and "reality" in the complexly ordering devices of marked symbolism, and develop, in fact, a craving for such devices, a symbol hunger . The crisis of complexity is met through a kind of enchantment that people accept in spite of or in tension with their common sense through a leap of faith into a commitment to the extraordinary and fascinating forms of the community's coherent and fascinating array of marked symbols. In chapter 9 and elsewhere we will present interview materials illustrating this movement in some individuals' recollections of childhood, adolescence, and maturity, a movement from simple certainties, to intellectual doubts about the family's and city's religious doctrines, to a conversion into "understanding," acceptance, and social solidarity—a conversion arguably associated with some of the personal implications of Bhaktapur's ubiquitous blood sacrifice.

For people living in Bhaktapur, the city and its symbolic organization act as an essential middle world, a mesocosm , situated between the individual microcosm and the wider universe as they understand it. This large aggregate of people, this rich archaic city, uses marked symbolism to create an order that requires resources—material, social, and cultural—beyond the possibilities and beyond the needs of a small traditional community. The elaborate construction of an urban mesocosm is a resource not only for ordering the city but also for the personal uses of the kinds of people whom Bhaktapur produces. Or at any rate has produced. Some of our acceptable cultural ancestors tried to make doubt a method, and finally succeeded in freeing us, as they believed, from marked symbolism, succeeded in making the symbolic "only" symbolic. The people of Bhaktapur are beginning to desert their continent in the great divide for familiar shores.

Chapter Three

Nepal, the Kathmandu Valley, and Some History

Introduction

Bhaktapur's mesocosm was built out of the materials available to it. In this chapter we will review something of the long history that helped form the present city, and out of whose debris it tried to build a seemingly timeless structure. That history, in turn, was much affected by the setting of the Kathmandu Valley—temperate, relatively disease-free compared to the southern jungles between Nepal and India, isolated and closed in by southern hills and those jungles to the south and by the Himalayas to the north, and with an enormously fertile soil, the essential support for the civilization that came to flourish there.

Nepal

Modern Nepal is a country of extreme geographic and ethnic diversity. At the time of our study (according to the 1971 census) 11.5 million people lived in a rectangular land some 500 miles long on its northeast-southwest axis and averaging some 100 miles in breadth. Totally landlocked, it is wedged in between India and Chinese Tibet "like a gourd between two rocks" as Prthvinarayana Saha, the Gorkhali founder of modern Nepal, put it in a phrase that all Nepalese leaders have always in mind. Nepal rises progressively in height from south to north from the low-lying jungles and plains of the Terai borderlands with India to the giant Himalayan ranges of the northern borders. In its jungles and

valleys and on the mountain slopes live a genetically, ethnically, and linguistically diverse set of peoples. There are by some accounts some seventy mutually unintelligible languages spoken, suggesting the corresponding cultural diversity of the country.[1]

Among these diverse peoples the Newars are peculiar. For they are themselves the remnants of a sort of nation, an older Nepal whose boundaries were usually the slopes of the hills surrounding the Kathmandu Valley. Hill people in the far reaches of the territory of modern Nepal still speak of the Kathmandu Valley as "Nepal." The Newars were the citizens of this now submerged polity whose arts and traditions still constitute most of "Nepalese Culture" when "Nepal" is represented in museums and in art and religious history as a South Asian High Culture. Modern Nepal began with the submerging of the Kathmandu Valley nation and the amalgamation of "over 50 principalities and tribal organizations" (Gewali 1973) into a much larger unity through the conquests of the western Nepalese Gorkhali hill tribes and their allies under the chief, Prthvinarayana Saha, who after a number of campaigns against the Valley profited from the internal disarray and jealousies of its Newar kingdoms to conquer them in 1768 and 1769.[2]

Because we are concerned with the Newars, not with "greater Nepal," our focus is on the Kathmandu Valley, which remained even after Newar incorporation into greater Nepal and some Newar dispersal (mostly as traders and businessmen to the developing cities of the new state) the main center of Newar life.

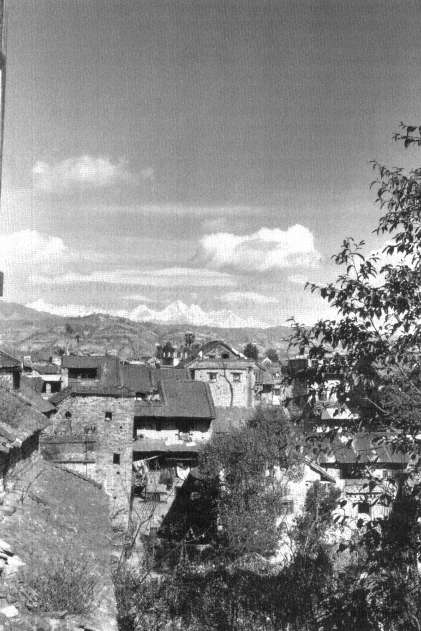

The Kathmandu Valley

The Kathmandu Valley is a rough ellipse measuring about 151/2 miles along its east-west axis and 12 miles at its greatest width, with a base area of some 218 square miles. The Valley is about 4,400 feet above sea level and ringed by hills that rise from 1,000 to 4,000 feet above the level of the Valley. Visible on the horizon to the north of the Valley in clear weather are the ranges of the high Himalayas. The Valley is the bed of an ancient lake. Its alluvial soil contains deposits of peat and of clays with high phosphate content which were traditionally dug and used as fertilizer. Now it is drained by a network of rivers that, almost dry during the dry months, swell during the rains and join in the main course of the Bagmati river, which drains the Valley at its southwestern boundary. Recorded mean monthly temperatures are reported as varying between maximums of 24°C (73.2°F) in June and a minimum of 7°C (44.6°F) in January. The climate is usually temperate, and it is rare

that temperatures dip a degree or two below freezing. The summers are first warm and dry, then more and more humid until the onset of the monsoon rains.

In the years 1967-1969 the Kathmandu Valley had between forty-four and sixty inches of annual rain (Central Bureau of Statistics 1974). Nearly half of the annual rainfall occurs during the monsoons of July and August, while the lowest rainfall, usually less than an inch in all, falls during November, December, and January, when the ground and air become progressively drier and dustier.

Valley farmlands, such as those around Bhaktapur, are in the flat-lands at the base of the hills and on terraces on the hill flanks. The fields are irrigated after the rainy season through a system of connecting ditches that are periodically unblocked to allow water to flow from collection basins in the hills. Various crops—rice, wheat, and a variety of vegetables (see chap. 4)—are successively raised in these fields during the course of the year.

The Kathmandu Valley, particularly the city of Kathmandu, is now the center for national government and administration. Light industry, tourism, and a multitude of commercial activities are centered there. It is estimated that about 5 percent of Nepal's people live in the Kathmandu Valley, some 600,000 people according to the 1971 census. They live[3] in the three major Valley cities of Kathmandu (150,402), Patan (59,049), and Bhaktapur (40,112),[4] a large number of secondary towns and villages, and in scattered hamlets and farms. Most of the country's ethnic groups are represented in the Valley. Census data in 1961 suggested that about half the Valley population were Newars.[5] ,[6]

Notes On Early Newar History

According to D. R. Regmi (1969, 14), the first written examples of the term "Newar" to denote the people and society of the Kathmandu Valley date from the seventeenth century, but, as he remarks, the term may well have had a long usage before then. Although, as we shall see, contemporary Newars in some contexts limit the "Newars" to the "climax" society that began to form in the time of the "medieval" Malla kings, as the society and culture seems to have developed more or less continuously from its most ancient roots, we can follow Regmi in referring to the Kathmandu Valley society, culture, and language from the earliest days until its capture by the Gorkhalis in the late eighteenth century as Newar.

Local inscriptions and foreign accounts, mainly Chinese, on which a

history of early Valley Nepal can be based date only from the fourth century A.D. In the absence of adequate archaeological studies, which may some day clarify and alter our conceptions of the early history, inferences about early periods are based on Nepalese chronicles and legends and on problematic allusions in Hindu epic literature.[7] There is still much debate on the interpretation of these sources for histories of political dynasties and events, and even for a correct chronology. But for the purposes of locating Bhaktapur, a provisional history can be sketched out.

The earliest written inscriptions (from the period of the Sanskrit-speaking court of the Licchavi dynasty) show that more than 80 percent of the place names in the Valley were non-Sanskritic. This supports a tradition that non-Sanskritic dynasties ruled early Nepal, perhaps from (at least) as early as the seventh century B.C. This society, referred to as "Kirata," was apparently of Mongoloid origin, speakers of a Tibeto-Burman language.[8] According to P. R. Sharma (1973, 67f. [spelling standardized]):

Despite the lack of proof, the Kirata tradition in Nepalese history is too deeply rooted to be dismissed easily. The Kiratas are a widely mentioned tribe in ancient Sanskrit literature, especially the Epics. Many references point to the northeastern Himalayan foothills as the home of these people. The Himalayas were still an area outside the sphere of Aryan domination, and the Kiratas therefore seem to differ from them racially. The Rais and Limbus [of contemporary Eastern Nepal] claim to be the Kiratas. The features of these people distinctly betray their Mongoloid origin. The use of the term Kirata in ancient literature seems to have been wide enough to encompass all groups [in Nepal] of Mongoloid stock. . . . The matrix of Nepalese culture in the valley must have been laid by these Kiratas. The modern inhabitants of the valley, the Newars, are believed to be an intermixture of Aryan and Mongoloid strains resulting from the unions between the Kiratas and the Aryans migrating from the plains of India. The early prototype of the Newari language might have struck its first roots also during this time, as the language is considered to be basically of the Tibeto-Burmese group. The liberal assimilation of the Indo-Aryan Sanskrit into the language proceeds only from the time of the Licchavis, who were responsible for introducing Sanskrit into the land.

By the first or second century A.D. , a Sanskrit-using and Prakrit-speaking court, the Licchavis,[9] had replaced the Kirata court. They were presumably related to the Licchavi rulers of Vaisali in Bihar in North India. This was the beginning of a continuing pattern of Sanskritic courts derived from North India ruling over a Tibeto-Burman-

speaking people.[10] Gradually the language and customs of the courts and the people were to blend in a Newar synthesis. Always within this synthesis, however, there were certain segments of religion and court life that followed Sanskrit models and some aspects of the life of the people that maintained residues of ancient Himalayan and Northern modes.

Irrigation of the Kathmandu Valley was developed under the Licchavis as many inscriptions attest,[11] with the construction of tanks and canals enabling farmers to husband and distribute the monsoon rains In concord with the rich soil of the Valley, irrigation led to the kind of agricultural surplus that eventually made extensive urbanization possible.

In the later days of Licchavi rule (from the late sixth century A.D. ) Tibet was developing a unified state, which was eventually to center at Lhasa. Now "Himalayan passes to the north of the Valley were opened. Extensive cultural, trade, and political relations developed across the Himalayas, transforming the Valley from a relatively remote backwater into the major intellectual and commercial center between South and Central Asia" (Rose 1974, 956). Much of the art and religion of the Newars and the Tibetans grew out of shared Indian sources, but also in mutual interchange and stimulation, and thus had many common features.

According to Prayag Raj Sharma (1973, 71):

In the early Licchavi period, Nepal, together with India undertook the cultural colonization of Tibet. Buddhism and its concomitant art spread from Nepal to Tibet in the 7th Century A.D. According to Tibetan tradition the famous Nepali King Amshuvarman[12] married his daughter to the first historical King of Tibet, Srongtsan-Sgam-po. Brikuti is said to have carried an image of Buddha among other things as her nuptial present to her husband, and during her lifetime in Tibet knowledge of Buddhism spread far and wide. . . . From the Seventh Century to the present days, Nepal's relationship with Tibet has been continuously reaffirmed. Nepalese [that is Newar] artists, especially bronze makers, painters, and architects went to work in Tibetan monasteries and seminaries. Buddhist scriptures were taken to Tibet to be copied or translated. Ranjana, an ornately elaborate Newari script became the divine script in Tibet. . . . The different Tantric schools which overwhelmed Tibet, also found their way from Nepal as well as India.

Nepal and her princess were, of course, only one component of the influences forming seventh-century Tibet, but one of considerable importance.

Nepal during the Licchavi period reflected most of the Indian reli-

gious developments of the times. Early inscriptions and art indicate that there were sects devoted to Visnu[*] , Siva, and the Buddha and their associated deities. Visnu[*] and his cult may have been more associated with the courts, and Siva, in this early period, perhaps somewhat more with the non-Ksatriya[*] classes.[13]

Some writers, notably the Sanskritist Sylvain Lévi (1905), believed that the major popular Indian religion of Nepal during this early period, the religion of the Tibeto-Burman segment of the people, was Buddhism superimposed on old Himalayan forms, while the religion of the court aristocracy was one or another sect of Hinduism. During this period both Theravada and Mahayana Buddhist monasteries were founded.

Lévi (1905, 255 [our translation]) proposed further that the first form of high Indian religion introduced into Nepal had, in fact, been Buddhism:

Buddhism, malleable and accommodating, was able to introduce itself into the organized life of the Newars, without greatly disturbing it; it discretely sowed Indian ideas and doctrines, and let the harvest ripen slowly. But from the moment it was ripe, a brutal adversary came to dispute it. Sacerdotal Brahmanism menaced with death by the triumph of heresies had skillfully searched for refuge in popular cults; it had adopted them, consecrated them, and took up the struggle with rejuvenated gods and a renewed pantheon.

The rejuvenated Hinduism that contested Buddhism was Saivism.

David Snellgrove noted that the earliest Kathmandu Valley monuments are "definitely" Buddhist. "It is likely therefore that Buddhist communities established themselves in this valley well before the beginning of the Christian era" (1957, 93f.), which would mean that the Licchavi dynasty found themselves from the beginning in contact with a Buddhist community, adhering also presumably to local Himalayan religious forms. Whether or not Buddhism preceded "Brahmanical religion," all early evidence shows them operating side by side, Brahmanical religion presumably being that of the "foreign" court and its "foreign" Brahmans and, Buddhism, being that of the "people." These speculations, like those regarding an early courtly Vaisnavism versus a popular Saivism, reflect a scholarly conviction that the Brahmanical ideal of an intimate organic interrelation of Brahman, king, and people was still on a far horizon.

There is also evidence for the Licchavi period of Sakti worship, of the worship of the sun and other astral deities, and some indication of early Tantric forms[14] that were to become of major importance for the Kathmandu Valley, and for Lhasa beyond it. These latter were the precur-

sors of the massive invasion of Tantrism which was to come later as a result of the dislocations produced by the Islamic invasions of India.

Bhaktapur's Beginnings

By the end of the Licchavi period most of the ingredients were present that were eventually to lead to the climax community of the royal Malla city-states, a community in which various preexisting elements developed fully, flourished, and became, for a time, related to each other in a closely interdependent and stable system.

The Licchavi dynasty fell in the ninth century, and there followed a period of historic and historiographic confusion out of which emerged the Malla dynasty. In this period Newar society and culture were to develop and flourish in its urban centers—Kathmandu, Patan, and Bhaktapur—and their dependent hinterlands. The Malla dynasty lasted in one form or another until the late eighteenth-century conquest by the Gorkhalis, which tranformed Nepal and the Newars into something different.

We must now begin to bring Bhaktapur toward the center of the scene, and consider the Malla period from its perspective. From the beginning of the thirteenth century there were a number of contesting ruling families bearing the name "Malla," interspersed with rulers who did not use this name. Eventually one man, Jayasthiti Malla, who married into the royal family of Bhaktapur and who began his reign in 1382, established an order and a dynasty that was to be remembered by the Newars as the Mallas, the Newar kings, their kings. His direct descendants ruled as Malla kings for more than four hundred years until the Gorkhali conquest of the Valley.

Bhaktapur seems to have been founded as a royal city by Ananda Deva,[15] who is believed to have reigned from 1147 to 1156 A.D. According to two early chronicles (D. R. Regmi 1965-1966, part 1, p. 180), Ananda Deva built a temple and royal palace in Bhaktapur.

According to the Padmagiri Chronicle, which substitutes Ananda Malla for Ananda Deva (Hasrat 1970, 49):[16]

Having left his throne in charge of his elder brother he [Ananda Malla] went to the western direction where he founded a new city which he called Bhaktapur, in which he erected 12,000 houses of all descriptions. When the city was built, Ananda Malla sent for [the goddess] Annapurna[*] Devi from Benares and had the goddess settled there in an auspicious hour. . . . Afterward he built a palace in Bhaktapur . . . where he beheld the Nine Durgas whose images he placed in a temple.

The chronicle published by Daniel Wright, known as "Wright's Chronicle,"[17] adds some details. Ananda Malla "founded a city of 12,000 houses, which he named Bhaktapur and included sixty small villages and seven towns in his territory. He established his court at Bhaktapur, where he built a Durbar; and having one night seen and received instructions from the Navadurga [Nine Durgas],[18] he set up their images in proper places, to ensure the security and protection of the town both internally and externally" (Wright [1877] 1972, 163).

The chronicles assert that the city was founded and developed as a royal center. There was something there before, however, and the attempts to construct a symbolically rationalized space that were to follow had to account for and work with preexisting structures. The most extensive work on the incorporation of previous structures into the "ordered space" of Bhaktapur is that of Niels Gutschow and his associates (Auer and Gutschow 1974; Gutschow and Kölver 1975; Gutschow 1975, Kö1ver 1980). They believe that the founding of Royal Bhaktapur involved a unification of a number of small villages that had developed in the area from perhaps the third century, following the development of irrigation in the Kathmandu Valley.[19]

Bhaktapur and the settlement that preceded its official Royal founding, has been referred to by a variety of names. Its early names were all Tibeto-Burman. According to the linguist Kamal Malla, its modern Newari name Khopa is derived from the earlier form khoprn , derived in turn from the Tibeto-Burman terms kho (river) and prn (field). The chronicles and inscriptions also refer to Bhaktapur as Khrpun, Makhoprn, and Khuprimbruma. The first usage of an Indic name, Bhaktagrama, dates from A.D. 1134 (Malla, personal communication). Its modern Nepali names are Bhaktapur, Bhadgaon, or Bhatgaon. Bhaktapur is taken to mean "city of devotees," the other names are said to mean "city of rice."

Bhaktapur, situated on the Hanumante river and bordered by rich farmland, was surrounded by a hinterland traversed by routes to the mountain passes to Tibet. Trade with Tibet became important for the Bhaktapur economy, and was to be of particular advantage during the periods when the Valley was divided into three semiindependent states.[20]

Bhaktapur eventually became the "metropolis of the Malla dynasty and the nerve-center of its culture and civilization" (Hasrat 1970, xxxix). The steps by which this happened can be only dimly glimpsed in records and monuments. Some historians believed that there was an early period of joint rule by the three Valley cities[21] which was some-

times peaceful, sometimes contested. But although earlier historians (e.g., D. R. Regmi 1965-1966, part I, p. 256) believed that the eventual hegemony of Bhaktapur in the Valley was not established until the later fourteenth century, later studies suggest that "since [its establishment in] the mid-twelfth century, Bhaktapur had been the capital city, de facto and de jure, and the Kings who titled themselves Malla continued to rule from it" (Slusser 1982, 54).

The fourteenth century marked the expansion of the empire of the Turkish Tughluq dynasty in northern India to and beyond the borders of Nepal. For the Newars the most important consequence was the dispersal of threatened Indian Buddhists and Hindus in the path of the Turks. Many of them came to the Nepal Valley where they greatly reinforced the Tantrism that was beginning to dominate and transform the earlier introduced forms of South Asian religion. The chronicles personify this movement in Harisimhadeva[*] , a king of Mithila, who was said to have been driven into exile in the Valley, where he became king of Bhaktapur, installing his kul deveta , or lineage goddess, Taleju, in the royal palace (Hasrat 1970, 52f.; Wright 1972, 175-177). Harisimhadeva's[*] conquest of Bhaktapur is legendary, although it is generally believed in by Bhaktapur literati, and we will hear much of him, but the introduction of the Maithili deity Taleju as the Newar king's royal lineage goddess (chap. 8) along with her associated Tantric cult seems to have clearly been due to the effects of Turkish movements in northern India during this general period.[22]

Another chronicle, the Gopalarajavamsavali, only recently made generally available, is a unique witness to what seems to have been the actual relation of Harisimhadeva[*] to Bhaktapur. As its editors note (Vajracharya and Malla 1985, xvi):

Unlike the later chronicles which almost unrecognizably distort the truth by presenting Harisimha[*] as a conqueror of Nepal and his descendants as legitimate rulers, the Gopalarajavamsavali notes that he was a political fugitive who died on his way to the valley, and his wife and son sought political asylum in Bhaktapur. Although they ultimately managed to rise to power by manipulating the local politics, the Queen and the Prince of Mithila had entered Bhaktapur as refugees.

The Maitili queen and her son, the prince, became involved, apparently, in struggles for power. Eventually a protege of hers, Jayasthiti Malla, whose marriage had been arranged to the queen's granddaughter, was to become ruler of Bhaktapur and the remembered architect of its present order.

Nepal itself suffered an invasion in the mid-fourteenth century when

Shams ud-Din Ilyas raided the Valley from Bengal in 1349.[23] "The Muslim invasion shook the foundations of the kingdom, the invader having destroyed the city of Patan, laid waste the whole Valley of Nepal. He indulged in an orgy of mass destruction and incendiarism, plundered the towns and sacrileged the temples of Pasupati and Svayambhunath" (Hasrat 1970, p. xli). According to another chronicle, the Gopala Vamsavli (folio 52 [a ], pp. 4-5), in Nepal Samvat 470 on the ninth day of the dark half of the month of Marga (January 1349), Sultan Shams ud-Din burned the city of Bhaktapur during seven continuous days. Petech (1958, 118-119) believed that this invasion was responsible for the disappearance of "all the monuments of ancient Nepalese architecture."[24]

Bhaktapur was now on the eve of its experiment in the construction of an ideal urban order. The partial destruction of the haphazard forms of a more ancient Nepal must have greatly facilitated and stimulated the undertaking.

Jayasthiti Malla and the Ordering of Bhaktapur

In 1355 A.D. , shortly after the Muslim invasion of Nepal, Jayasthiti Malla, "a figure of obscure lineage and controversy with regard to his status as a sovereign ruler" (Hasrat 1970, xli), married the granddaughter of Rudramalla, a powerful Bhaktapur noble. After a period of shifting rulers and alliances he eventually emerged as the paramount ruler of Nepal, beginning his de jure reign in 1382.[25] "To Jayasthiti Malla goes the credit of saving the kingdom from the throes of disintegration and confusion. He curbed the activities of the feudal lords, brought the component units of the kingdom into submission, and with a strong hand, restored order" (Hasrat 1970, xlii).

Jayasthiti Malla was credited by some of the later chronicles—and by the present people of Bhaktapur—with the establishment of many of the laws and customs of Bhaktapur, particularly those involving caste regulations, with standardizing weights and measures, with establishing an order. Let us review some of the achievements traditionally ascribed to him. "Each caste [in Bhaktapur now] followed its own customs. To the low castes dwellings, dress and ornaments were assigned, according to certain rules. No sleeves were allowed to the coats of Kasais [butchers].[26] No caps, coats, shoes, nor gold ornaments were permitted to Podhyas [untouchables]. Kasais, Podhyas, and Kulus were not

allowed to have houses roofed with tiles, and they were obliged to show proper respect to the people of castes higher than their own" ("Wright's chronicle," Wright 1972, 182f.). The chronicles credit Jayasthiti Malla with dividing the people into a large number of "castes" (sixty-four in some accounts, thirty-six in others). "The four highest castes [here varna[*] is meant; see chap. 5] were prohibited from drinking water from the hands of low caste people, such as Podhyas or Charmakaras. If a woman of a high caste had intercourse with a man of a lower caste, she was degraded to the caste of her seducer" (Wright 1972, 186f.). According to the Padmagiri chronicle, "He constituted a fine for all such persons as follow the profession of others, as if a blacksmith follow the profession of goldsmith, he shall be fined" (Hasrat 1970, 56).

"He ordered that all the four castes of his subjects should attend the dead bodies of the Kings to the burning-ghats, and that the instrumental music of the Dipaka Raga should be performed while the dead bodies were being burned. . . . He constituted for each of the 36 tribes a separate masan or place for burning their dead and the corpses were decreed to be conveyed by four men proceeded by musicians" (Wright 1972, 182). Jyasthithi Malla classified houses and lands and standardized a system of measurement. "To the four principal castes, viz., the Brahman, Kshatri, Vaisya, and Sudra, were given the rules of Bastuprakaran and Asta-barga for building houses" (Wright 1972, 184). He changed the criminal laws. Previously criminals had been punished "with blows and reprimands, but this Raja imposed fines, according to the degree of the crimes" (Wright 1972, 182).

Jayasthiti Malla "made poor wretched people happy by conferring on them lands and houses, according to caste" (Wright 1972, 187). This particular aspect of reordering may explain, in part, reports of one set of laws that seem to run counter to the rigid codifying of social hierarchy and custom generally attributed to him. That is, Jayasthiti Malla "made many laws regarding the rights of property in houses, lands, and birtas[27] that hereafter became saleable" (Wright 1972, 182). Or as Padmagiri's chronicle has it, "He allowed his subjects to sell or mortgage their hereditary landed property whenever occasion required it." One may assume that this increased negotiability of property rights had something to do with the reforming of the status system and facilitated the economic base of the new regulations.[28]

A manuscript in the Hodgson Collection (vol. 11, n.d.) collected between 1820 and 1844 entitled "Institutes of Nepal Proper under