The Coalescing of a Pro-SRO Movement

Between 1967 and 1973, the political situation of hotel life changed dramatically. The climate of American political activism and awareness of minority needs had reached critical mass. As part of reforms aimed at urban renewal, arguments began to be heard locally and in Congress for the inclusion of hotel residents in public housing programs.[38] Responding to these arguments, Congress passed the Uniform Relocation Act in 1970. This policy change marked 1970 as a major pivot year in the political history of SROs. For the first time, redevelopment agencies and other federally funded groups were legally required to recognize people living in hotels as bona fide city residents; if a residential hotel was to be demol-

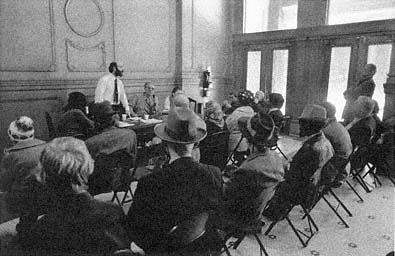

Figure 9.13

A hotel tenants' meeting in San Francisco's South of Market, 1973. Members

of Tenants and Owners in Opposition to Redevelopment (TOOR) confer with

their lawyers in a hotel lobby.

ished as part of a public project, the agency had to help the hotel tenants find new housing, just as if they were apartment dwellers. Twenty years of official removal had made SRO units hard to find, and the process of assisting tenants was difficult. Most critically, the budget outlays were substantial: each hotel dweller was to receive the $200 household dislocation allowance, compensation for moving costs, and up to $83 a month for four years if the new housing cost more than 25 percent of the individual's income; the total was not to exceed $4,000.[39] Suddenly hotel residents were both visible and very expensive for the urban renewal process.

Simultaneously, SRO tenants had learned their rights and with community activists had organized themselves more effectively. Because urban renewal was early and done on a large scale in San Francisco, the local movement against it was an important national example. In 1968, South of Market hotel tenants began organized protests of the relocation for what became Moscone Convention Center and Yerba Buena Gardens (fig. 9.13). In December 1969, courts issued the first restraining order against the San Francisco Renewal Agency, and the court battles continued for four years. The residents proved to the court that adequate replacement housing did not exist in the city, and the court forced the SFRA to develop over 1,500 units of new housing in the area. Developed by a nonprofit community group, Tenants and Owners Development Corporation (TODCO), the first new replacement housing opened in 1979.[40]

San Francisco was only one early center among several engaged in full-fledged fights to revise plans for urban renewal and to save SROs. In Boston SRO tenants stopped progress on a renewal program. So did tenants in New York's Greenwich Village and on the Upper West Side. The New York Mayor's Office of SRO Housing was opened in 1973 to work on social programs and tenant protection laws. Other groups were working to rehabilitate hotels and improve their management. In 1975, a pro-SRO group in New York City, Project FIND, leased and moved into the 308-room Woodstock Hotel, located near Times Square.[41] These projects saved only a few hotels from demolition but did create a new and embarrassing climate of public relations. Suddenly hotel owners, city housing authorities, redevelopment agencies, and other people with anti-SRO views had to work hard to prove that residential hotels were an urban blight of culturally aberrant buildings where only marginal people lived.

Unfortunately, the Uniform Relocation Act could not decree an instant change in the SRO attitudes of all housing officials in Washington, D.C., or in local agencies; at first, the act exacerbated harassment of residents and hastened hotel demolition. From 1970 to 1980, an estimated one million residential hotel rooms were converted or destroyed, including most of the Yerba Buena area (fig. 9.14).[42] Hotel owners generally did not want help to stay in business, in large part because of the potential profits from the expansion of downtown offices. In the 1970s, downtown office construction suddenly started a new boom and developers began to offer hotel owners handsome prices for their properties. Then, as now, the land underneath most residential hotels had more market value than the buildings. In New York, an empty hotel was worth two to three times that of an occupied building because the new speculator owner could more quickly rehabilitate it for a new use or tear it down.[43] Then, as now, to encourage the perception of hotels as blight, public and private owners understated the positive side of hotel living and overemphasized the problems in bad hotels. In day-to-day management and long-term goals, the lines between public and private ownership often blurred. Redevelopment agencies (through eminent domain) and city governments (through tax foreclosure) frequently became unwilling landlords for remaining residential hotels. To manage their hotel programs, they often hired anti-SRO people from the property industry, not pro-SRO people from social welfare offices.

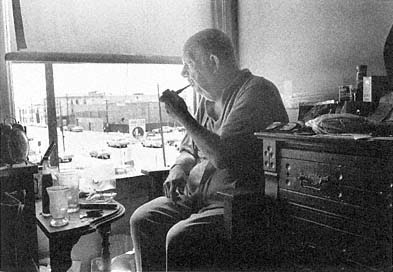

Figure 9.14

Ken Roth, a South of Market hotel resident in the 1970s, watching the

demolition of his San Francisco neighborhood for the Yerba Buena project.

For the stubbornly positive SRO buildings with sound structures and tenants neither marginal nor easy to dislodge, both public and private landlords developed an arsenal of tools to create problems where none have existed before. Although the techniques were perfected in the early 1970s, many remain in use. To generate vacancies, one of the most effective means was to reverse normal management principles and to harass the tenants: replacing friendly, long-term staff with churlish employees; suddenly lowering the standards for admissible tenants; and loosening security, stopping maid service, or permanently removing clean linen from stock. Other owners deliberately aggravated tenants by shutting off heat and hot water for long periods, locking toilet rooms, not repairing (or entirely closing down) elevators in six-story and eight-story buildings, plugging room locks, seeing that mail and messages were "lost" (particularly for tenants who were demanding their rights), not letting Meals on Wheels attendants deliver food, spraying for roaches while tenants were still in the room, taking the furniture out of the lobby, falsely advertising no vacancy so the hotel emptied, and sending gangs of thugs along with eviction notices to intimidate tenants. The agents of one hapless San Francisco hotel owner had the poor judgment to use the roach-spray-in-an-occupied-room technique while one of Mayor Dianne Feinstein's aides was visiting the tenant. One New York landlord went at the steel stair landings of his building with a hammer and chisel; after five flights of stairs had thus

"collapsed," the building had to be vacated because of failure to comply with fire safety laws.[44]

In San Francisco, struggles like these eventually led to the International Hotel dispute and eviction of 1977, which was another turning point in national opinion about SRO homes and SRO people. After eight years of nationally publicized eviction struggles, at 3:00 A.M., 330 police officers and sheriff's deputies converged on the hotel, which stood at the edge of Chinatown. After vociferously protesting the court orders to do so, the sheriff had finally come to evict about forty elderly Chinese and Filipino residents who remained in the 184-room hotel. On nearby sidewalks more than 2,000 demonstrators protested. Many of the public knew the hotel's location not only because of its residents but also because of its large basement nightclub, the hungry i, which in earlier years had headlined Barbra Streisand, the Kingston Trio, Dick Cavett, Bill Cosby, Dick Gregory, and Woody Allen.[45] After the eviction battle, the owner of the property, the Four Winds Corporation of Singapore, immediately razed the building. Fifteen years later, the site was still empty, except for the archways of the remaining basement walls, where the hungry i had once been. There, on cold nights, homeless people huddled to get out of the wind.

The tenants in the International Hotel lost their single-room homes, but like tenants in earlier cases, their fight helped to raise new questions about the intersections of hotel life, property rights, and social services. For instance, the year following the eviction, the staff of the U.S. Senate used the case for the introductory example in an information paper about the SRO crisis.[46] Owing to the fights of the 1970s, the formerly invisible realms of hotel life finally began to appear regularly in public spotlights, with front-page newspaper articles headlined "Rooms of Death," "Heatless Hotels," and "Struggle over Downtown Continues." Through the 1980s, the New York Times prominently featured SRO stories nearly once a week. The Gray Panthers and other senior groups also came to be instrumental in several fights.[47]

Another important example of the turnaround process since the 1970s is the experience of Portland, Oregon. About the same time as the last fights at the International Hotel, a private group remodeled Portland's Estate Hotel with a city loan; in 1978, neighborhood leaders formed the nonprofit Burnside Consortium (now called Central City Concern) to coordinate services and to preserve other housing. In 1979,

Andy Raubeson was appointed director of the consortium and saw immediately that SRO hotels were a prime priority for his skid row clientele. "It just seemed too obvious," he says, "that we had to champion the housing stock." His organization began leasing and then buying hotels, eventually renovating more than five hundred units.[48] The Burnside experience emphasizes the growing realization that proper management—often subsidized by a nonprofit organization—is a key to maintaining low-cost hotel life. As part of the Portland action, in 1980, U.S. Rep. Les AuCoin, a Democrat from Oregon, persuaded Congress to make SROs eligible for federal low-interest rehabilitation loans and then for Section 8 housing funds. These and other successful programs have put Portland in the forefront of municipal efforts to preserve SROs.[49]

With the federal Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1981 and the Stewart B. McKinney Bill in 1987, hotel housing moved further toward better housing status and became eligible for a few other subsidies. With cruel irony, these official changes of heart began just before the Reagan and Bush administrations slashed public housing funds by 80 percent.[50] The widespread implementation of the new policies was thus deferred.